Translating evidence from neuroscience into classroom practice can be problematic for many reasons (Howard-Jones, 2014). Findings from a lab setting may not always be transferable to a classroom. #ScienceOfLearning with @FutureLearn #learning #education #edutwitter

TIL that we mostly only use 10% of our brain is a neuro-myth. Our brain is always active. #learning #education #edutwitter

Another neuromyth: learning styles matter

An extensive review found that there were no clear implications for pedagogy arising from any existing models of learning styles (Coffield et al., 2004).

Despite the lack of evidence, the idea remains popular (Howard-Jones, 2014).

An extensive review found that there were no clear implications for pedagogy arising from any existing models of learning styles (Coffield et al., 2004).

Despite the lack of evidence, the idea remains popular (Howard-Jones, 2014).

Neuromyth: Differences in hemispheric dominance (left brain, right brain) can help explain individual differences amongst learners.

The idea we use the left side of our brain in one task and the other side of our brain in another myth. #edutwitter #education #learning #brain

The idea we use the left side of our brain in one task and the other side of our brain in another myth. #edutwitter #education #learning #brain

Neuromyth: Children are less attentive after sugary drinks and snacks.

The research linking sugar and attention is mixed at best (Mahoney et al., 2007), with some studies even showing benefits to attention. #edutwitter #education #learning #brain #Neuroeducation #neuroscience

The research linking sugar and attention is mixed at best (Mahoney et al., 2007), with some studies even showing benefits to attention. #edutwitter #education #learning #brain #Neuroeducation #neuroscience

Neuromyth: Learning problems associated with developmental differences in brain function cannot be remediated by education.

The brain is plastic (it can change) and studies have shown that education can help remediate both the behaviours and the brain function differences.

The brain is plastic (it can change) and studies have shown that education can help remediate both the behaviours and the brain function differences.

Within the subcortical region in the brain, there is the ‘reward system’. This has much to do with how we respond positively to (approach) a learning situation. The subcortical structures that play important roles are:

Hippocampus: laying down memory

Amygdala: emotional response

Hippocampus: laying down memory

Amygdala: emotional response

Often a neuromyth contains a kernel of truth, which may have been either misinterpreted or become distorted over time (Howard-Jones, 2014). For e.g., another very common neuromyth is that drinking less than 6 to 8 glasses of water a day can cause the brain to shrink. #neuromyth

Every learner’s brain is different and students will vary in what most engages their attention and the extent to which they can control their attention (Furukawa et al., 2016; Gaastra et al., 2016).

#neuroeducation #neuroscienceineducation #education #educhat

#neuroeducation #neuroscienceineducation #education #educhat

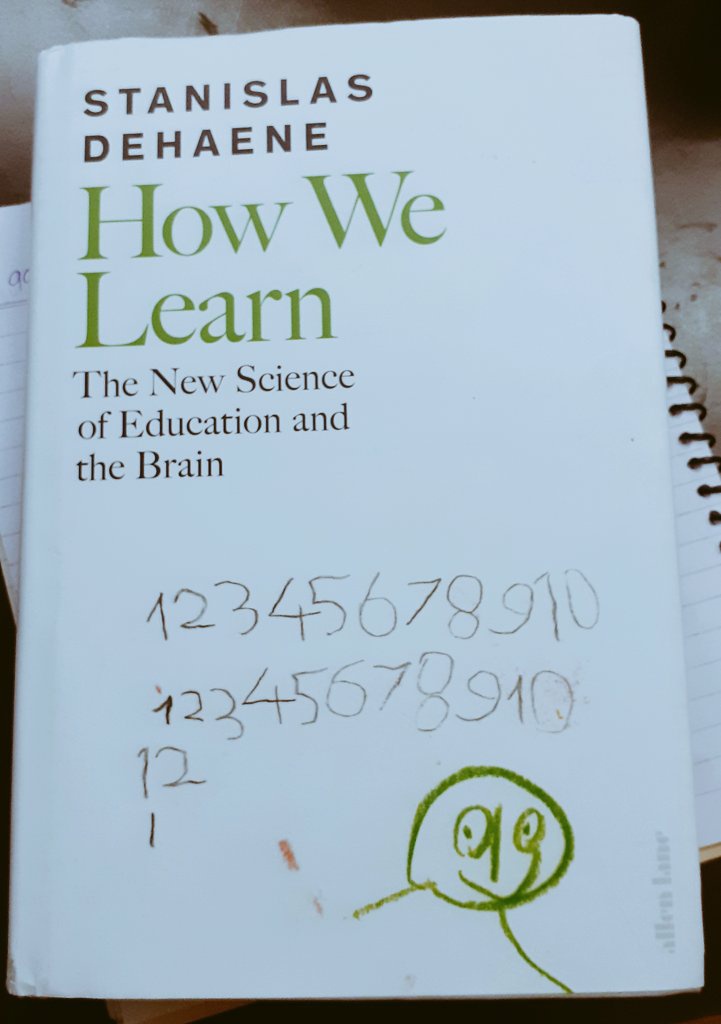

@StanDehaene's book uses real life examples and case studies to debunk many of the myths related to learning and education. Many of his insights are quite counter-intuitive (or at least go against the traditional understanding). Need to devote a separate thread for this book.

Most classroom rewards are social (praise, gold stars, points etc) and contribute to self-esteem and social standing. (Izuma et al., 2008; Farooqi et al., 2007; Howard-Jones et al., 2016; Knutson et al., 2001; Koepp et al., 1998).

#neuroscience #neuroeducation

#neuroscience #neuroeducation

A large number of factors influence how the brain responds to reward and it varies from one individual to the next, including age (Van Leijenhorst, 2010), gender (Hoeft et al., 2008), being impulsive (Joseph et al., 2016), hormonal and genetic differences (Caldu and Dreher, 2007)

Novel contexts can help engage students initially with a new topic, or help encourage them to apply and practice their learnt knowledge in new scenarios, which is important for consolidating their understanding, memory and transfer of that knowledge (Min Jeong et al., 2009).

Thinking together can also help activate brain responses. A teacher can encourage three types of group talk to reinforce and help students consolidate the concept.

1) Disputational Talk

2) Cumulative Talk

3) Exploratory Talk

#neuroscience #neuroeducation #education #edutwitter

1) Disputational Talk

2) Cumulative Talk

3) Exploratory Talk

#neuroscience #neuroeducation #education #edutwitter

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter