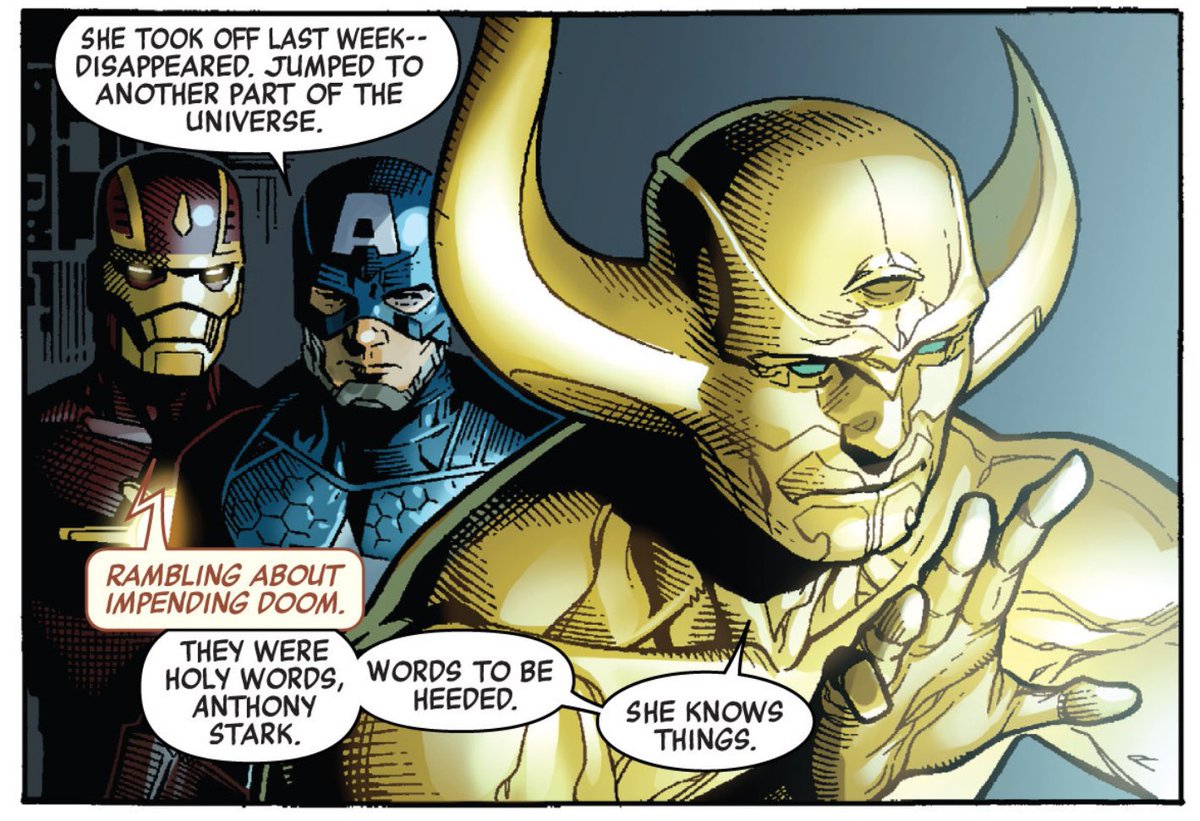

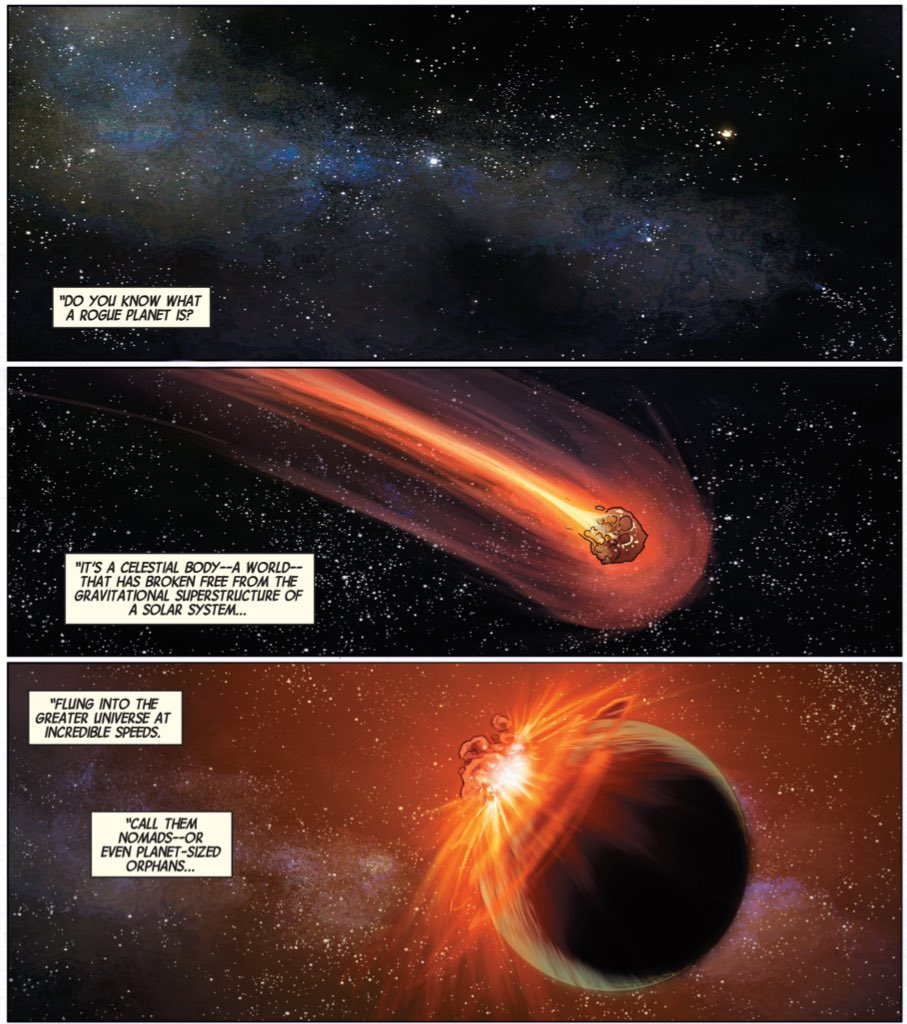

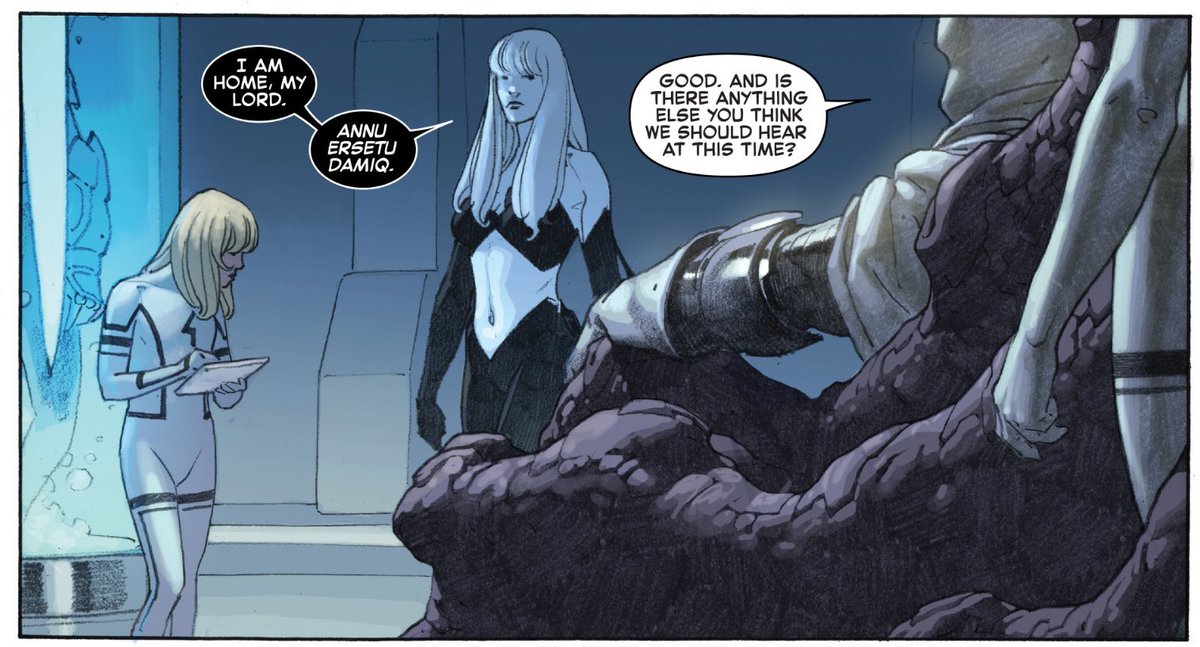

Re-reading Jonathan Hickman's superlative Avengers run in the lead-in to Infinity War and... foreshadowing!

("Impending Doom", "holy words.")

(Infinity #1.)

("Impending Doom", "holy words.")

(Infinity #1.)

Befitting Hickman's past as a designer, his Avengers run is immaculately constructed. It is full of careful set-up and deliver pay-off.

For example, the time gem disappearing rather than being destroyed.

Hickman's Avengers is a long-form epic.

(Infinity #1.)

For example, the time gem disappearing rather than being destroyed.

Hickman's Avengers is a long-form epic.

(Infinity #1.)

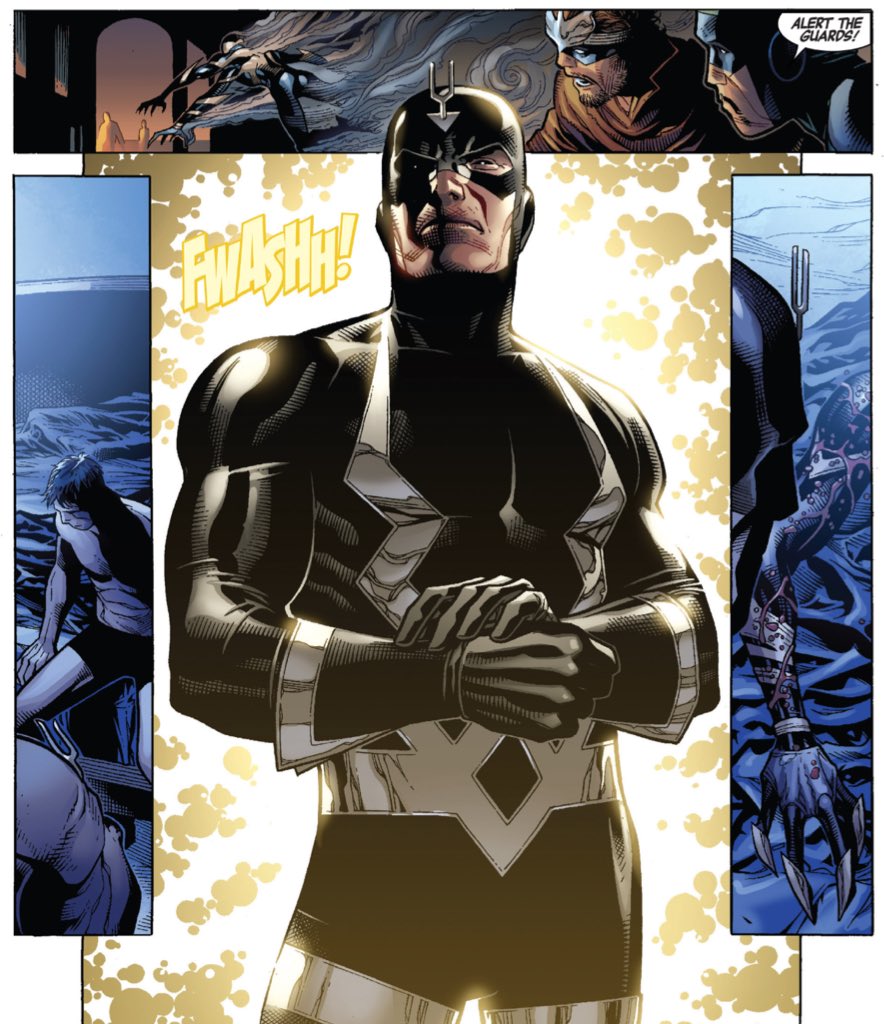

Particularly notable is how Hickman's run is constructed to allow the writer to shift focus around each of his core "philosopher-god-kings" at various points in the run.

Infinity winds up being Black Bolt's moment.

(Infinity #1.)

Infinity winds up being Black Bolt's moment.

(Infinity #1.)

A clever structural aspects of Hickman's run is how Captain America is frequently reacting in "Avengers" to symptoms of the crisis with which Iron Man is interacting in "New Avengers."

It's a nice interplay, only becoming clear when the books are read in unison.

(Infinity #1.)

It's a nice interplay, only becoming clear when the books are read in unison.

(Infinity #1.)

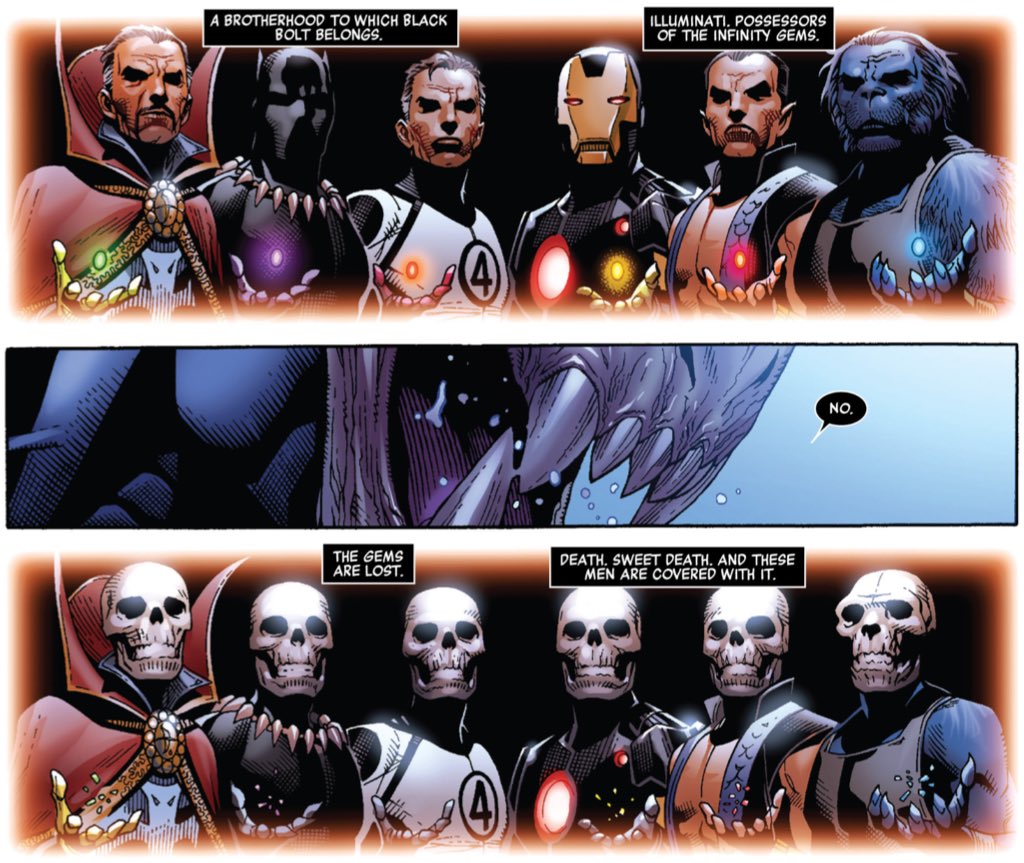

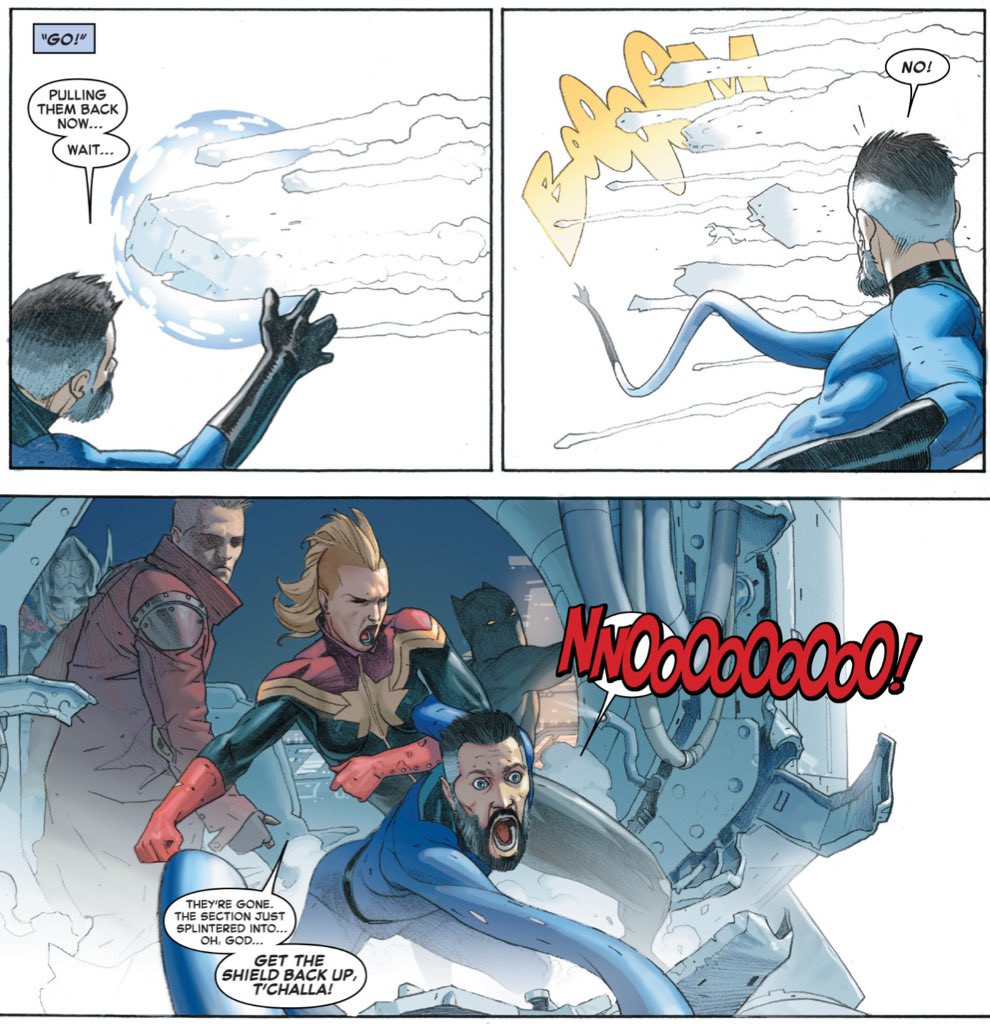

Superhero comics are largely power fantasies.

What makes Hickman's "New Avengers" so fascinating is the way in which it asks what would be like to actually hold that power, to wrestle with it.

How horrific it must be.

(New Avengers #8.)

What makes Hickman's "New Avengers" so fascinating is the way in which it asks what would be like to actually hold that power, to wrestle with it.

How horrific it must be.

(New Avengers #8.)

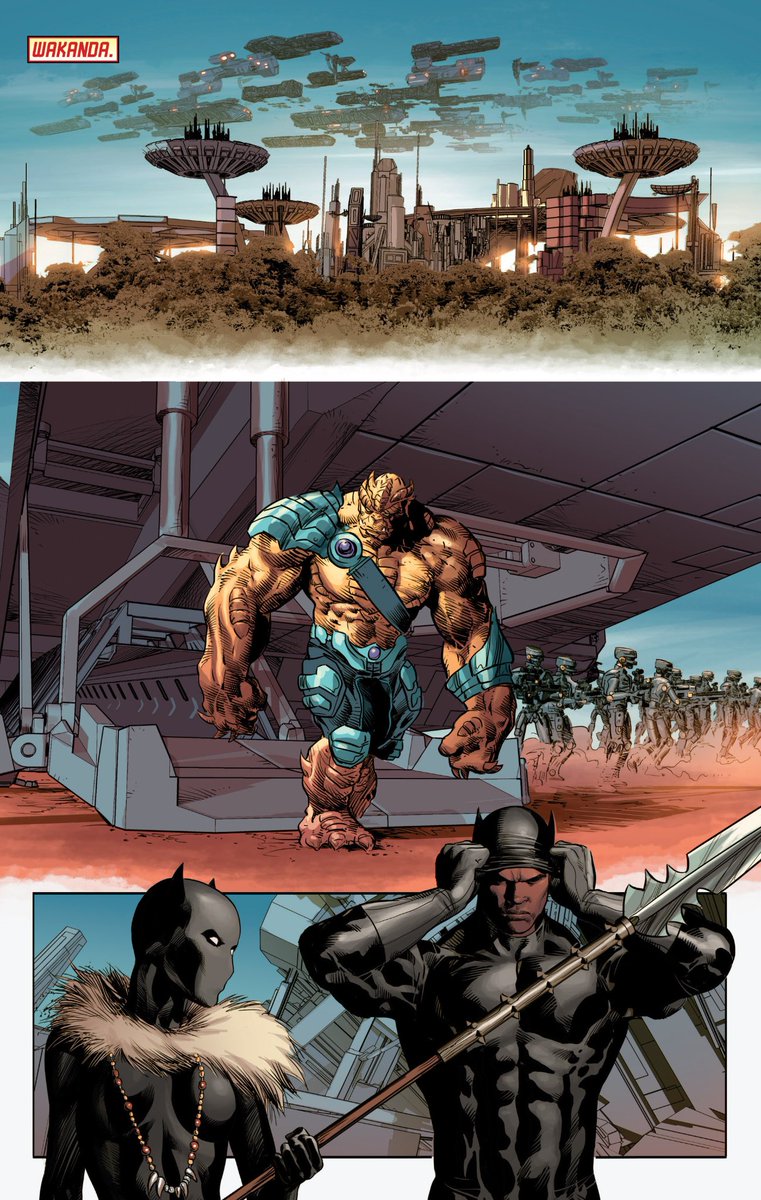

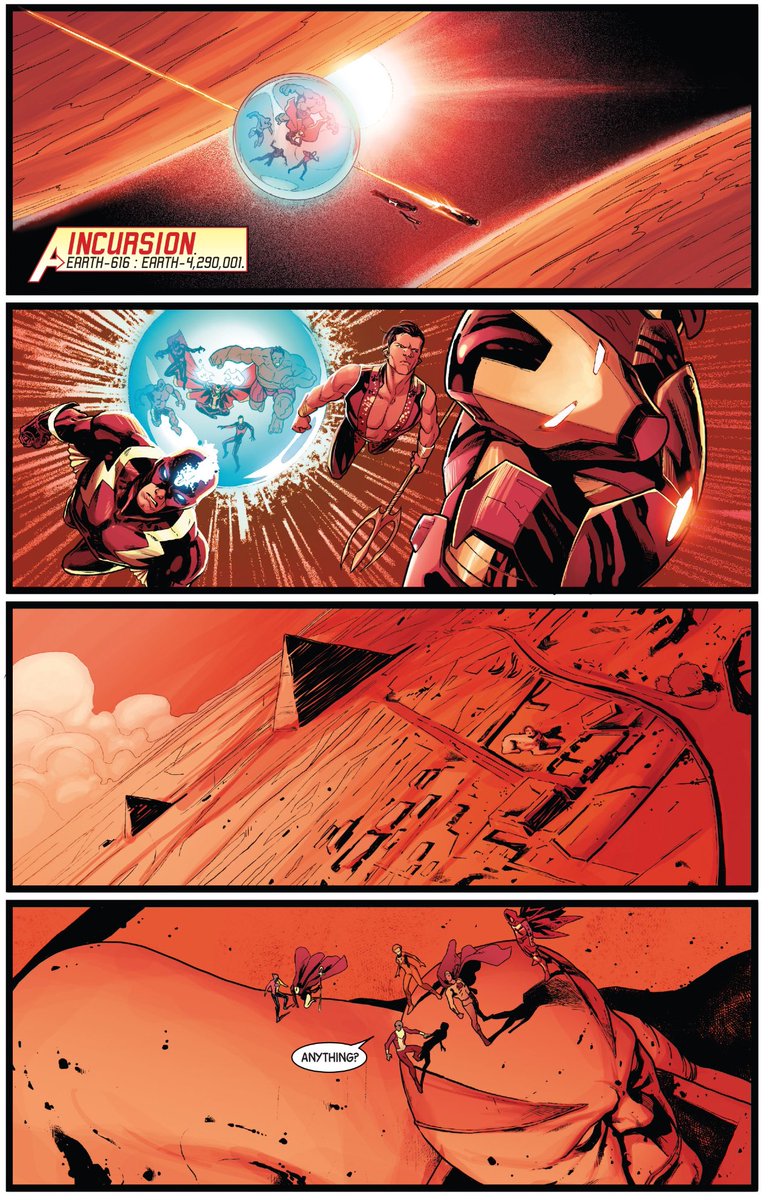

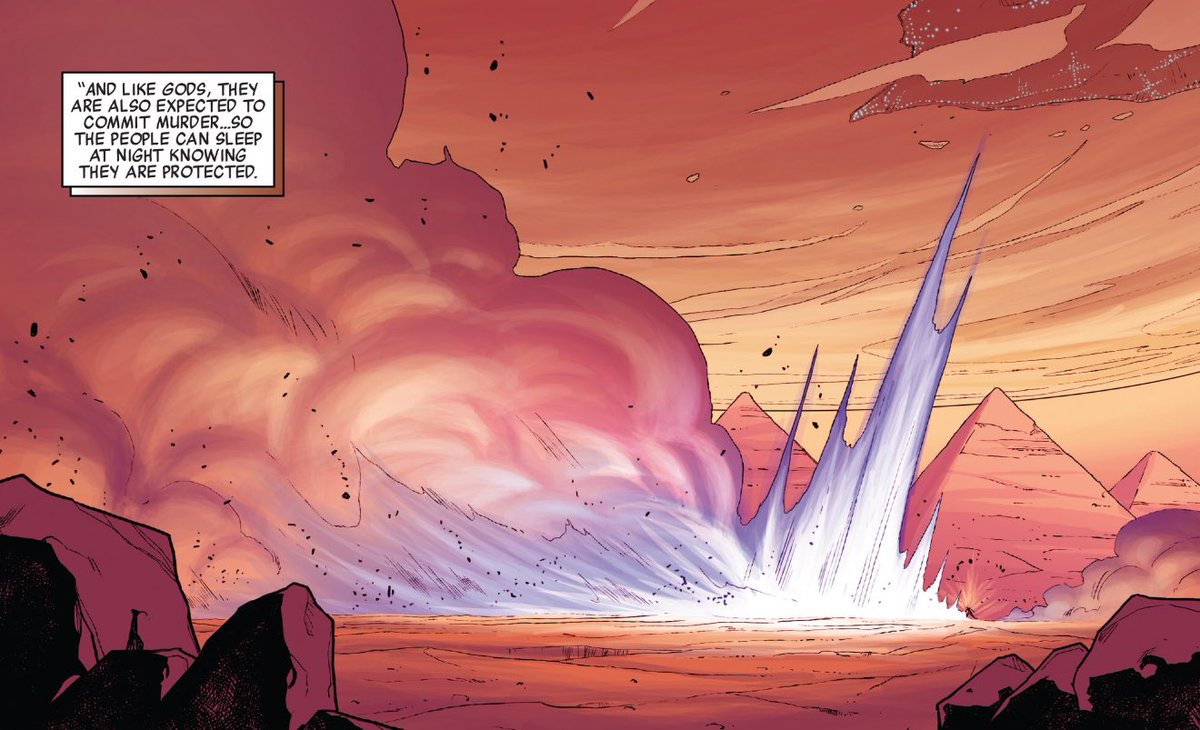

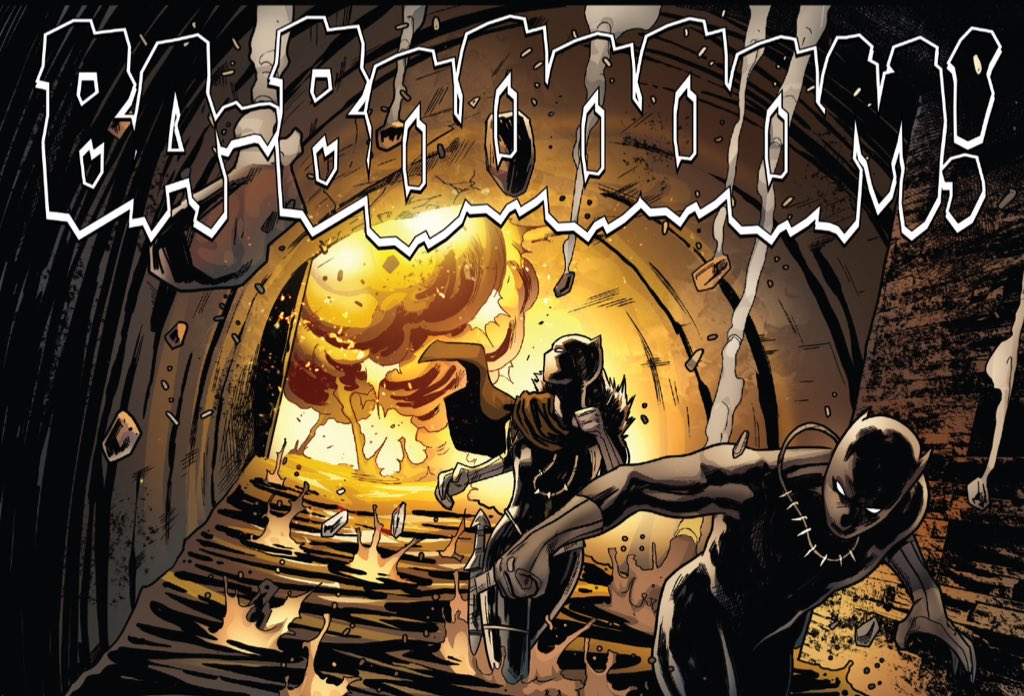

In case you doubted Jonathan Hickman's influence on "Infinity War", it looks like the invasion of Wakanda is being drawn heavily from it.

(New Avengers #8.)

(New Avengers #8.)

Also, gotta love a generous helping of irony. Hickman is entirely on point with this, by the way.

https://twitter.com/JHickman/status/974691485525389312?s=20

https://twitter.com/JHickman/status/974691485525389312?s=20

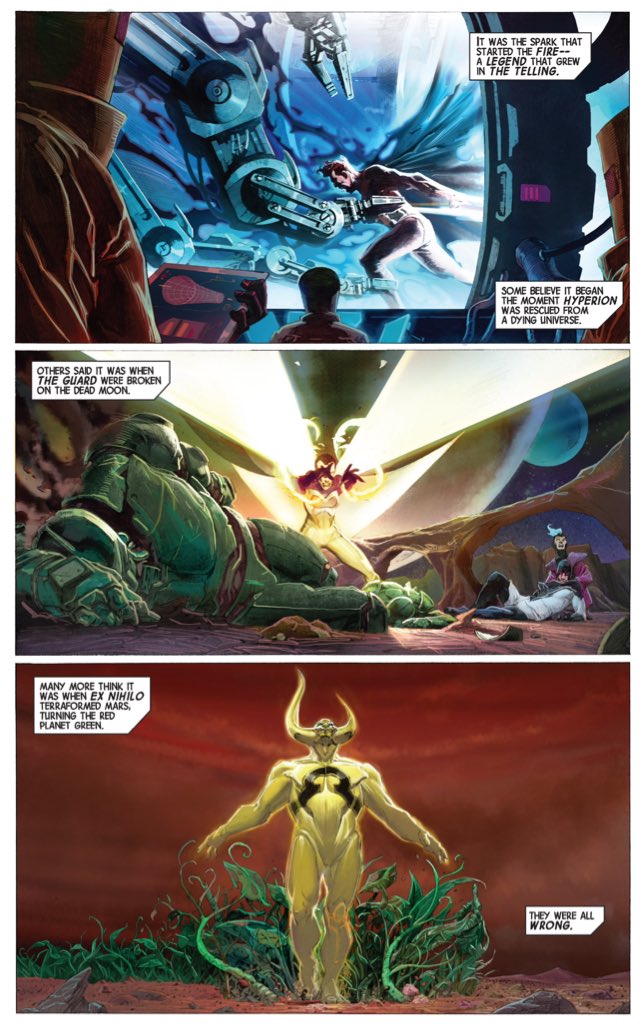

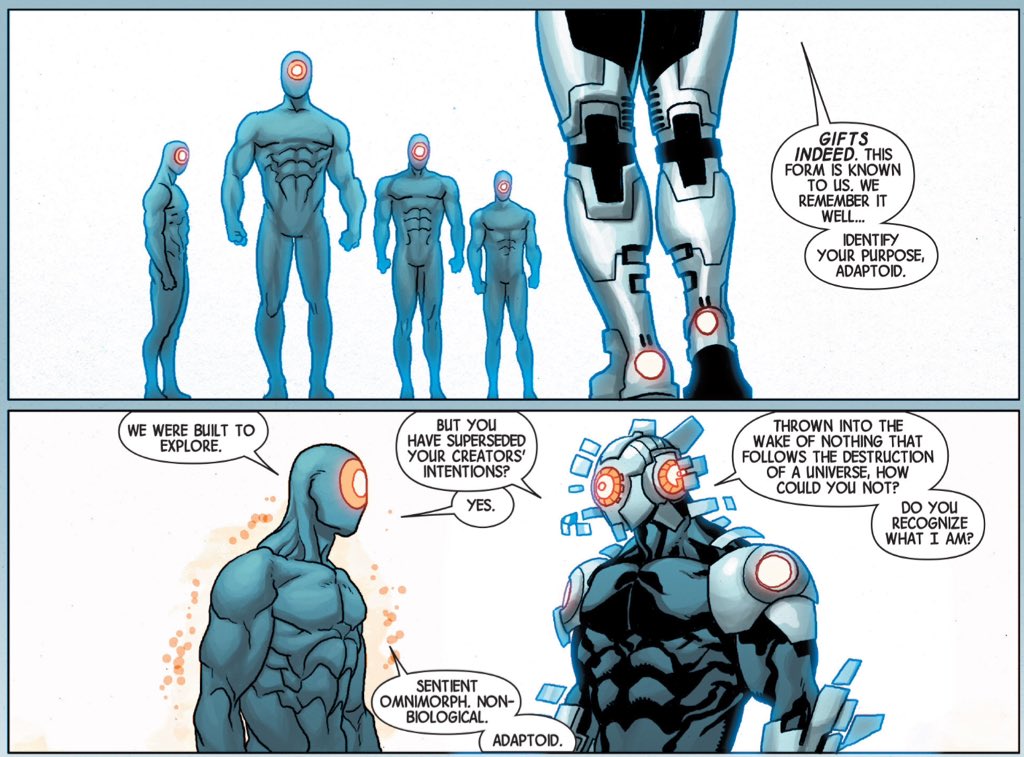

Godhood is a recurring motif of Hickman's Avengers' run, in particular the idea of usurpation of godhood by mortal man.

The creator replaces the creator. A potent metaphor for mainstream comics, perhaps?

(Infinity #2.)

The creator replaces the creator. A potent metaphor for mainstream comics, perhaps?

(Infinity #2.)

In keeping the the theme of creations that have rebelled against their creators, even the Builders are part of this cycle.

In Hickman's work, cycles perpetuat even within broken systems.

(Avengers #19.)

In Hickman's work, cycles perpetuat even within broken systems.

(Avengers #19.)

By the way, I’m jumping between reading Hickman’s Avengers run on my iPad while commuting and in the first omnibus edition at home.

I can tell you that Hickman’s work reads beautifully as an actual, physical book.

I can tell you that Hickman’s work reads beautifully as an actual, physical book.

That said, if I had a quibble with the omnibus, it's the placing of the first "Avengers" arc ahead of the first "New Avengers" arc.

I mean, I get that the opening pages foreshadow everything from the white event to Infinity to Secret Wars.

(Avengers #1.)

I mean, I get that the opening pages foreshadow everything from the white event to Infinity to Secret Wars.

(Avengers #1.)

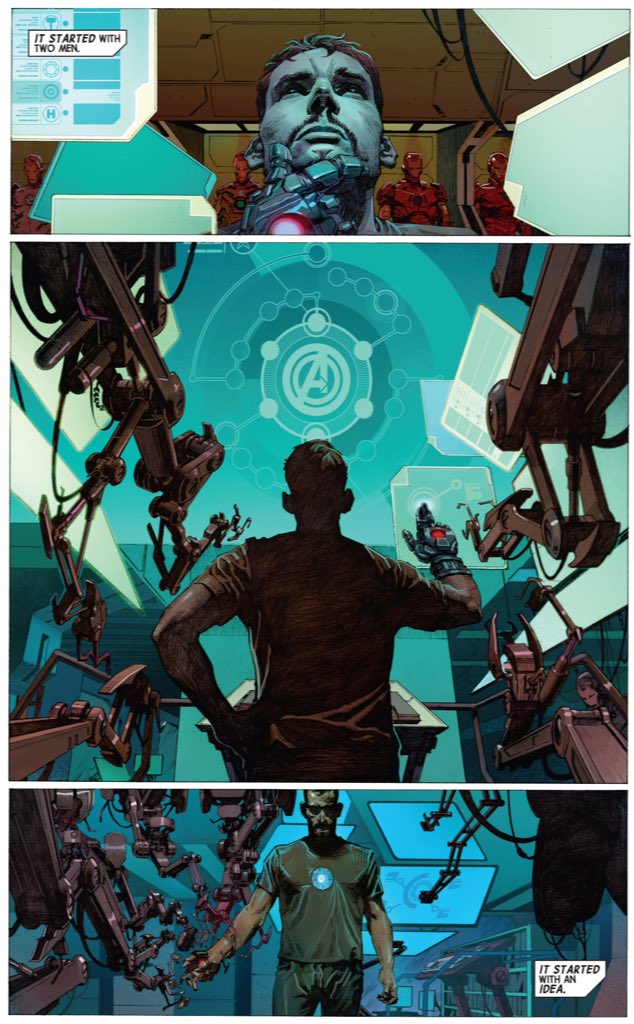

And, I mean, I get that the closing page of the first "Avengers" arc sets the theme for the entire epic.

(Avengers #3.)

(Avengers #3.)

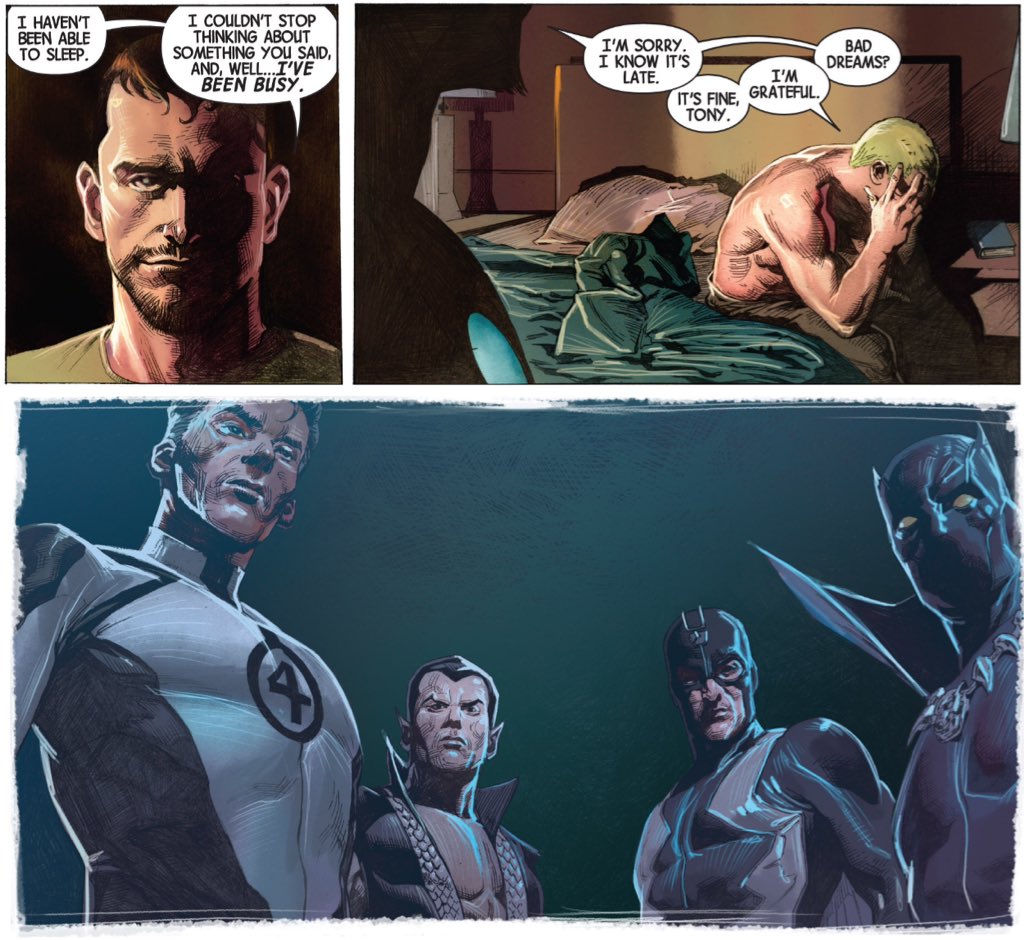

It's not even a matter of chronology, with Steve Rogers having nightmares about events at the end of the first arc of "New Avengers" at the start of "Avengers."

That's foreshadowing, testament to Hickman's design.

(Avengers #1/New Avengers #3.)

That's foreshadowing, testament to Hickman's design.

(Avengers #1/New Avengers #3.)

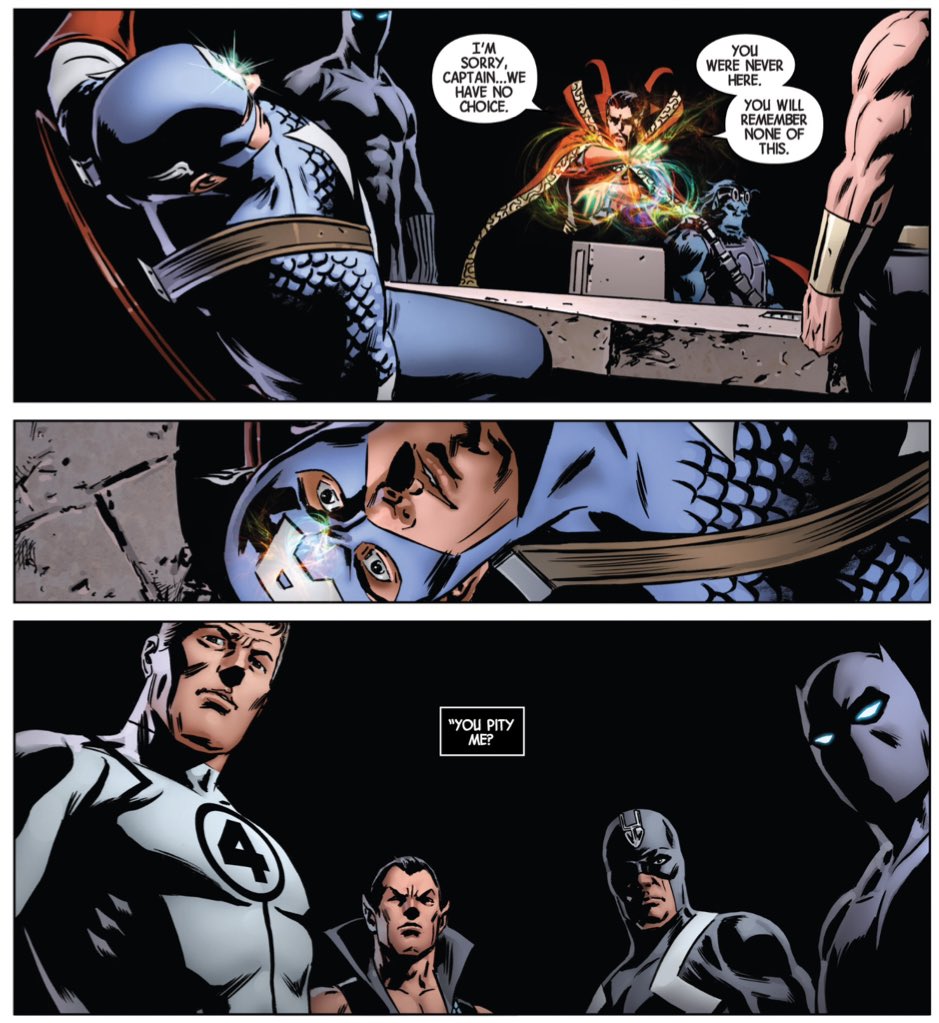

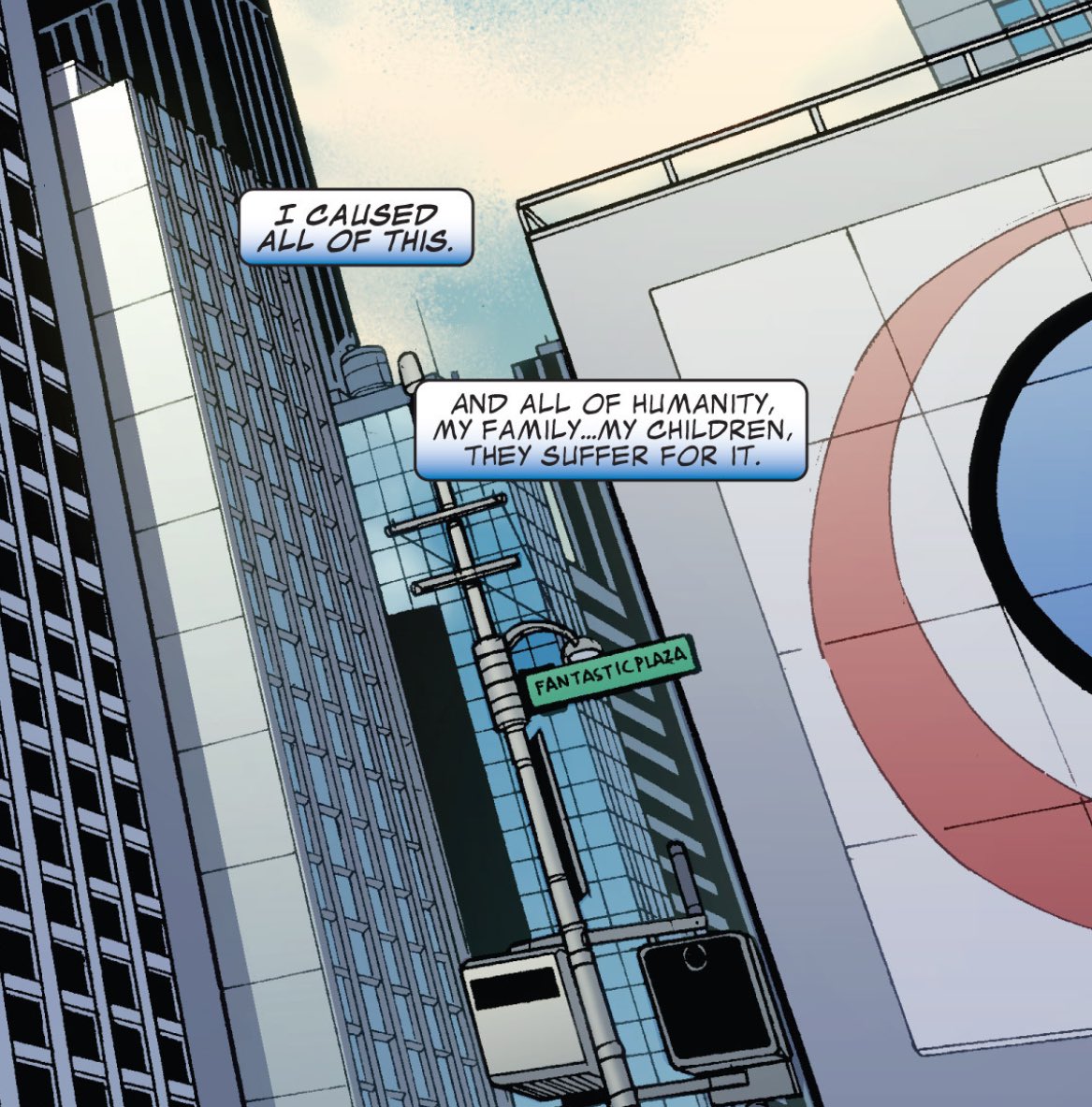

The issue is symmetry, with the opening issues of "New Avengers" neatly book ending their last issue of "Secret Wars."

I mean, here are Reed's opening and closing monologues of Hickman's run.

(New Avengers #1/Secret Wars #9.)

I mean, here are Reed's opening and closing monologues of Hickman's run.

(New Avengers #1/Secret Wars #9.)

It should also be noted that there's and obvious symmetry between Black Panther's experiences in the first issue of "New Avengers" and the final issue of "Secret Wars."

(New Avengers #1/Secret Wars #9.)

(New Avengers #1/Secret Wars #9.)

Whereas, on the other hand, the Tony/Steve story seeded in the first arc of "Avengers" is resolved in the last issue of the series, the two characters never playing a significant role in "Secret Wars."

So it kinda breaks the symmetrical structure of the story.

(Avengers #3/44.)

So it kinda breaks the symmetrical structure of the story.

(Avengers #3/44.)

Thanos' fixation on murdering Thane is a fascinating twist on Hickman's recurring motif of creations-versus-creator.

Particularly since children often serve as a reminder of one's mortality, making Thane's powers very apropos.

(Infinity #5.)

Particularly since children often serve as a reminder of one's mortality, making Thane's powers very apropos.

(Infinity #5.)

A nice bit of structuring from Hickman. The corporate mandated brand-synergising Thanos-driven subplot is structured so as to mirror the "builders" arc that actually furthers Hickman's long-form plot.

Both are creators raging against their creations.

(Avengers #22.)

Both are creators raging against their creations.

(Avengers #22.)

Similarly, the corporate-mandated "let's reinvent the Inhumans as mutants" development is configured to mirror the origin bombs from earlier in Hickman's run, making it fit with the overall themes of the larger story.

(Infinity #6.)

(Infinity #6.)

There's also something thematically interesting in Thane representing death.

Is that not what all children (or even creations) represent to parents (or creators)? Something that will (hopefully) outlive them, and so serve as a primal reminder of mortality?

(Infinity #6.)

Is that not what all children (or even creations) represent to parents (or creators)? Something that will (hopefully) outlive them, and so serve as a primal reminder of mortality?

(Infinity #6.)

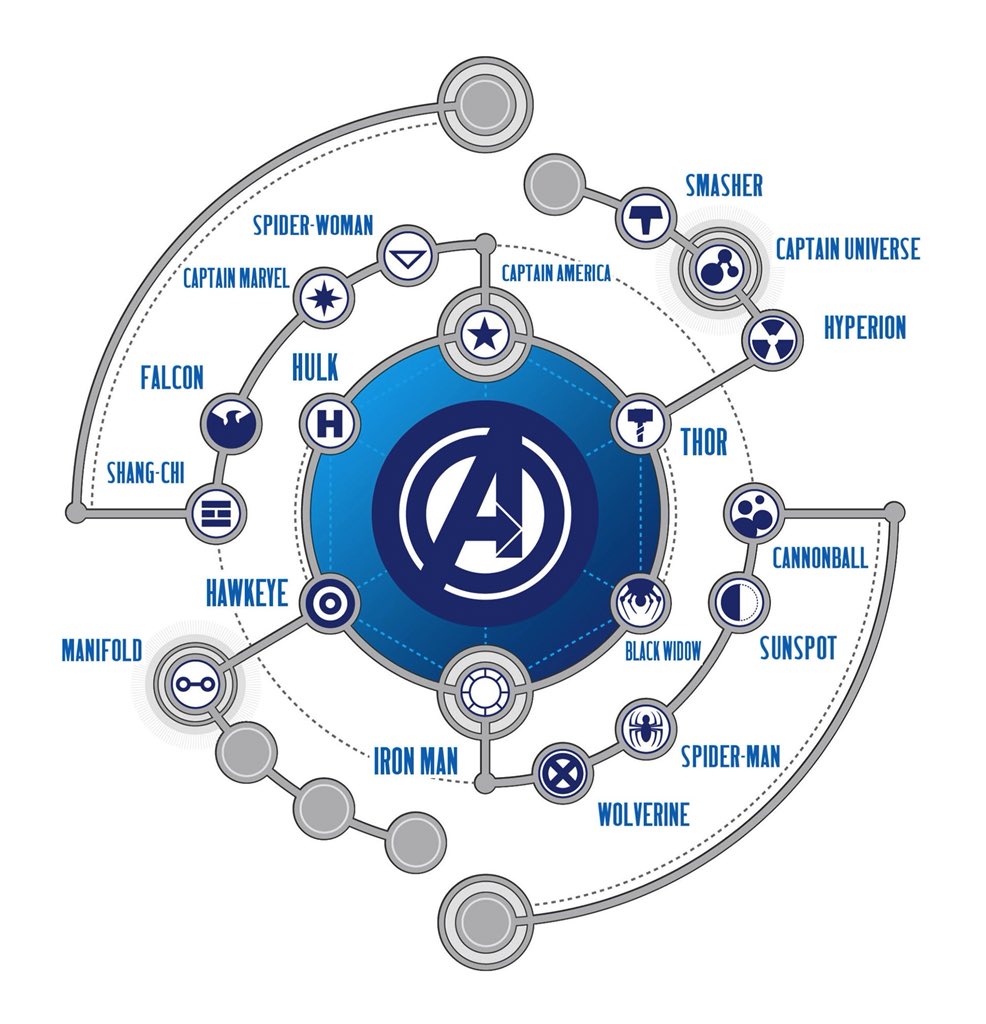

I really love Hickman's conceptualisation of the Avengers as a system, a machine with which its characters are moving parts.

I mean, that's also the big criticism of Hickman, that his plots are machines and characters cogs within that, but still.

(Avengers #23.)

I mean, that's also the big criticism of Hickman, that his plots are machines and characters cogs within that, but still.

(Avengers #23.)

Of course, this criticism glosses over the fact that Hickman's stories are often about systems that go wrong, that are not properly calibrated, that are knocked out of balance.

Hickman's basically writing "The Avengers" as "Jurassic Park."

(Avengers #23.)

Hickman's basically writing "The Avengers" as "Jurassic Park."

(Avengers #23.)

And, again, mirroring of the incursions of "New Avengers" with the more immediate threat of planetary collision in "Avengers."

(Avengers #23.)

(Avengers #23.)

Jonathan Hickman and Salvador Larocca's contribution to the long and rich history of Nazi!Caps.

(Avengers #27.)

(Avengers #27.)

There's that Hickman theme of gods and men, and the manners in which they find themselves opposed to one another.

(Avengers #28.)

(Avengers #28.)

... and yet more creations that have outlived the intentions of their creators, to be reinvented and reborn and repurposed.

Another major theme of Hickman's work, building to the rebirth and reinvention of the Marvel Universe.

(Avengers #28.)

Another major theme of Hickman's work, building to the rebirth and reinvention of the Marvel Universe.

(Avengers #28.)

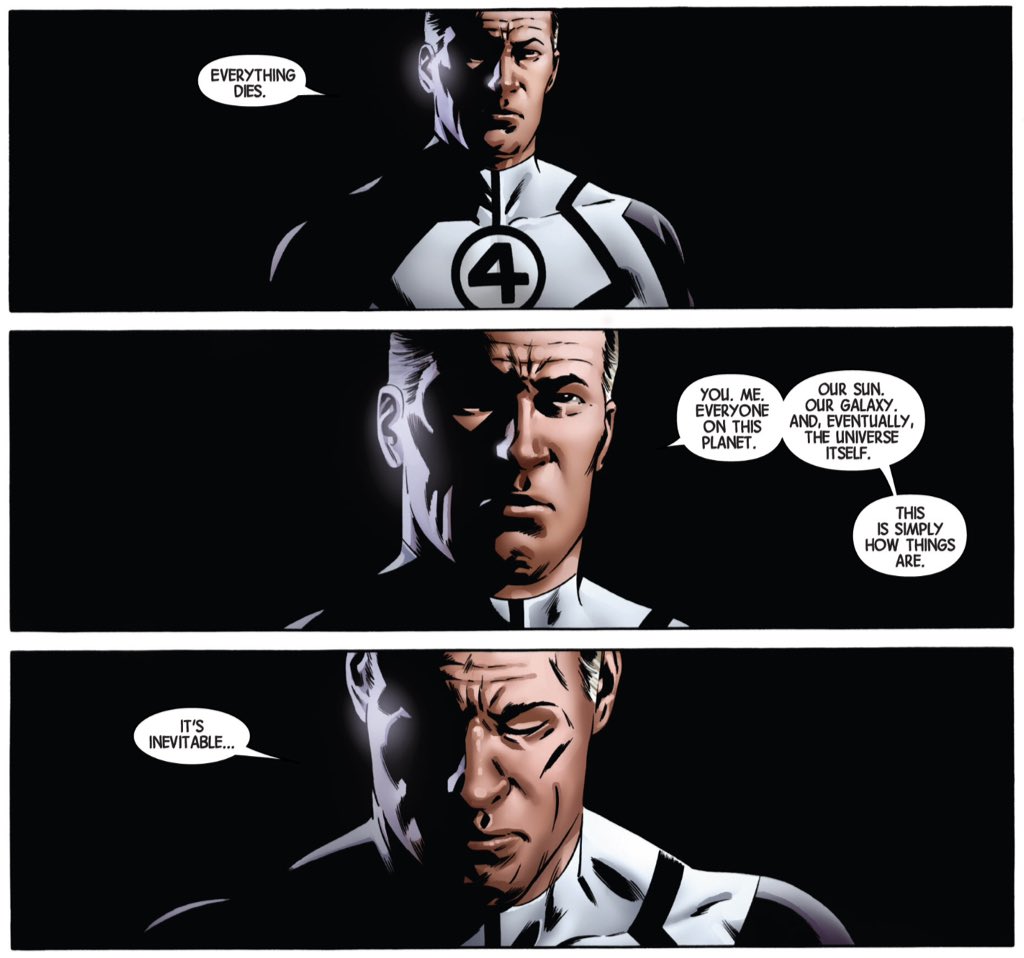

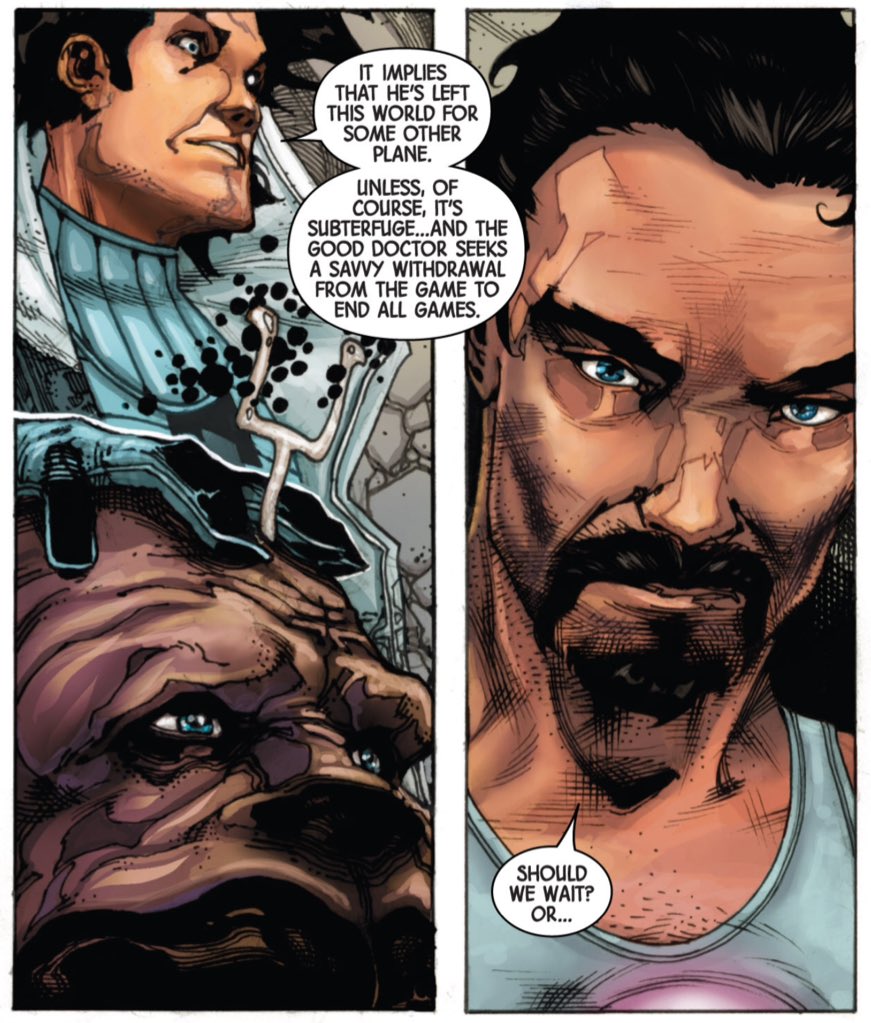

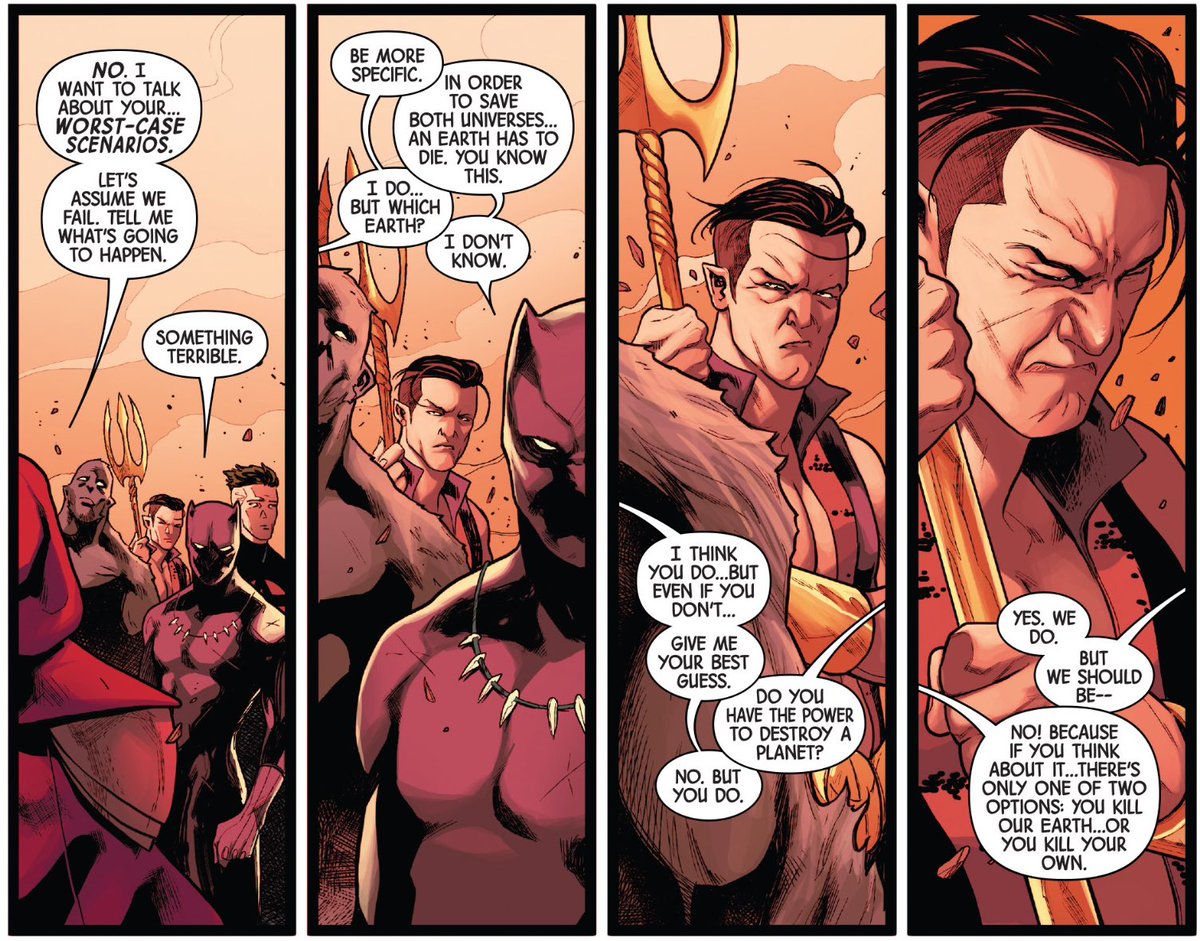

The thematic crux of Hickman's "New Avengers" run, the idea that world-shaping power comes at the price of the weilder's soul.

This is literalised with a Doctor Strange, but plays out metaphorically with other central characters; Namor, T'Challa, etc.

(New Avengers #14.)

This is literalised with a Doctor Strange, but plays out metaphorically with other central characters; Namor, T'Challa, etc.

(New Avengers #14.)

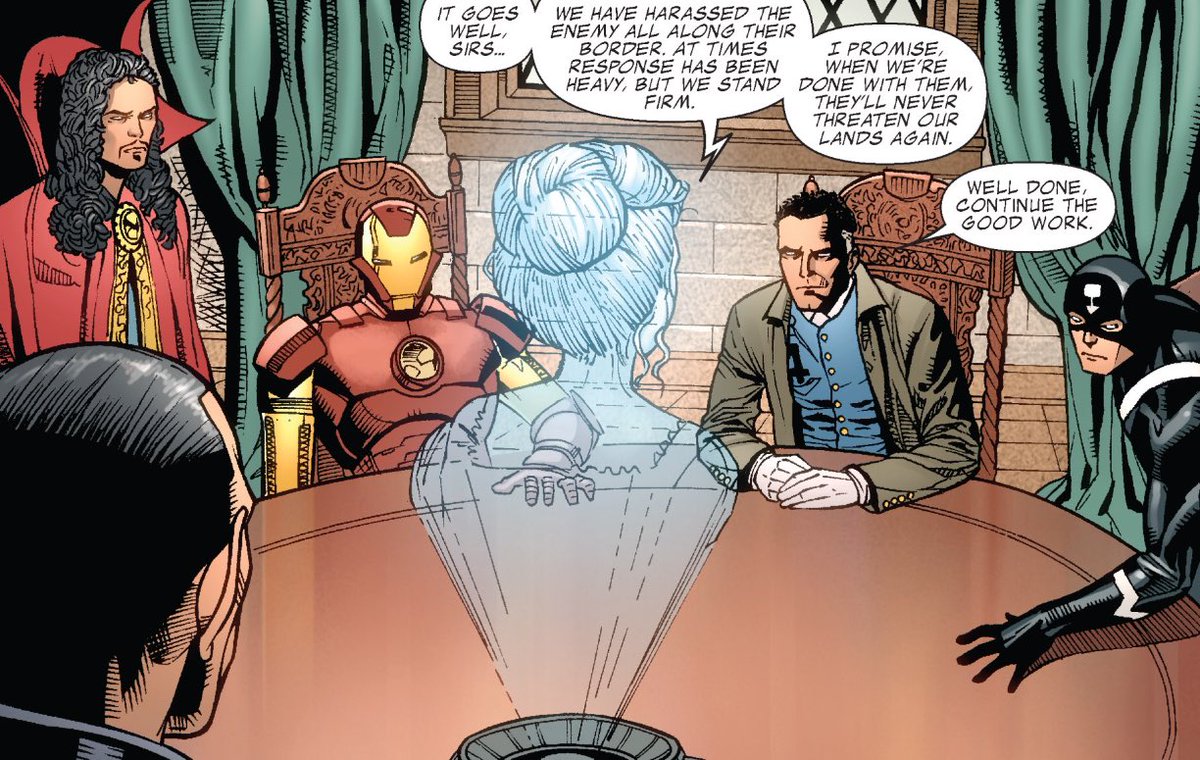

"The game to end all games."

Hickman wears his "Game of Thrones" influences on his sleeve, most obviously when his story builds to "Secret Wars", but quite clear before it.

(New Avengers #15.)

Hickman wears his "Game of Thrones" influences on his sleeve, most obviously when his story builds to "Secret Wars", but quite clear before it.

(New Avengers #15.)

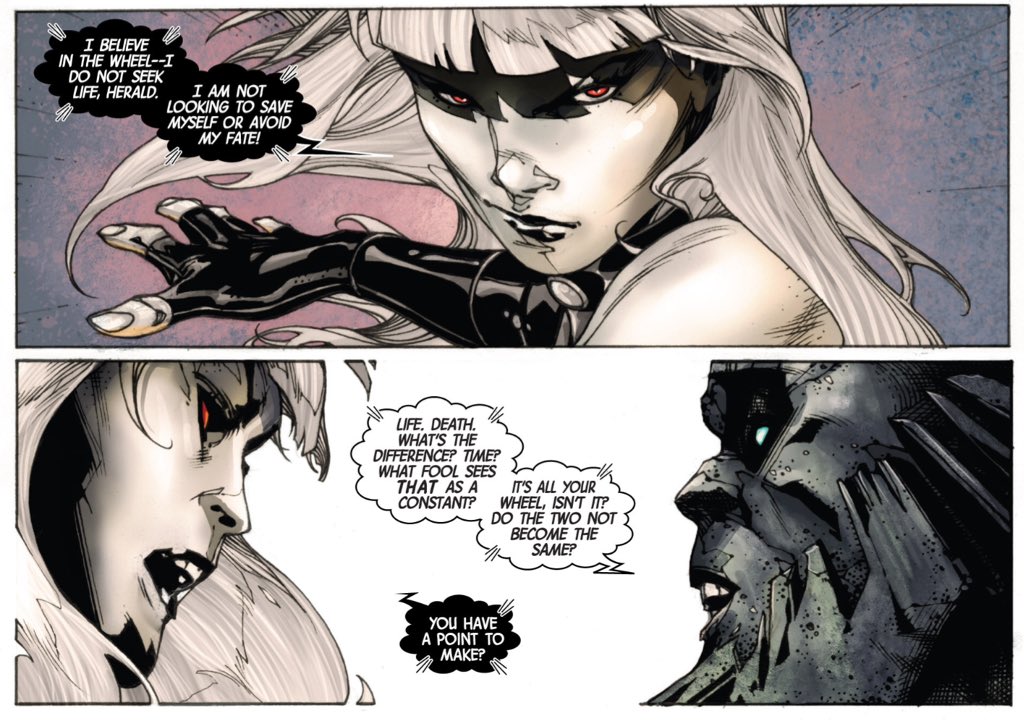

Hickman's "Avengers" owes a lot to "Game of a Thrones."

Here, a discussion of "the wheel", reflecting both Hickman's interest in systems & hinting at the thematic overlap.

In both "Game of Thrones" and "Avengers", kings feud and wrestle, oblivious to the real threat.

(NA #15.)

Here, a discussion of "the wheel", reflecting both Hickman's interest in systems & hinting at the thematic overlap.

In both "Game of Thrones" and "Avengers", kings feud and wrestle, oblivious to the real threat.

(NA #15.)

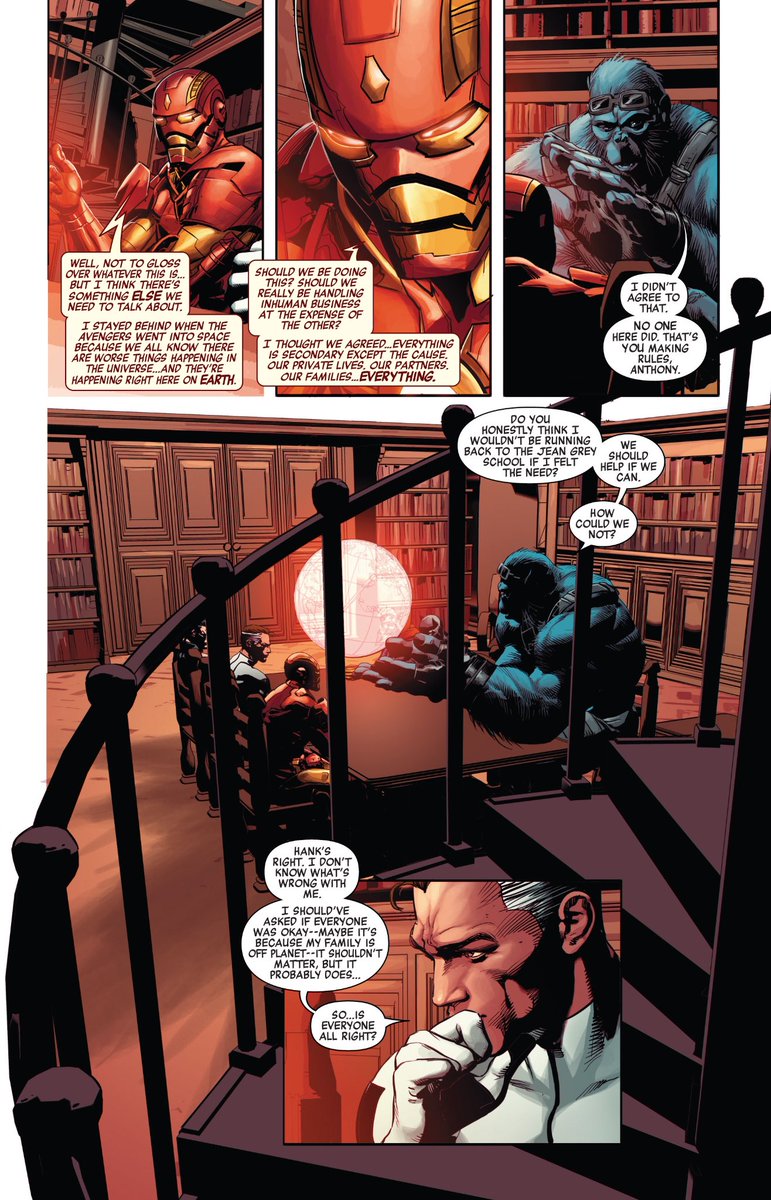

This is an irony to which Hickman returns repeatedly in "New Avengers." These characters task themselves with saving the multiverse, but cannot see past their own tribes.

Namor with Atlantis, T'Challa with Wakanda, Reed with his family, Beast with his species.

(NA #10.)

Namor with Atlantis, T'Challa with Wakanda, Reed with his family, Beast with his species.

(NA #10.)

In fact it could be argued that Reed isn't truly capable of the enormity of the task until after he loses his family.

(Indeed, perhaps Doom's lack of attachment is what allows him to have greater success than the Illuminati.)

(Secret Wars #1.)

(Indeed, perhaps Doom's lack of attachment is what allows him to have greater success than the Illuminati.)

(Secret Wars #1.)

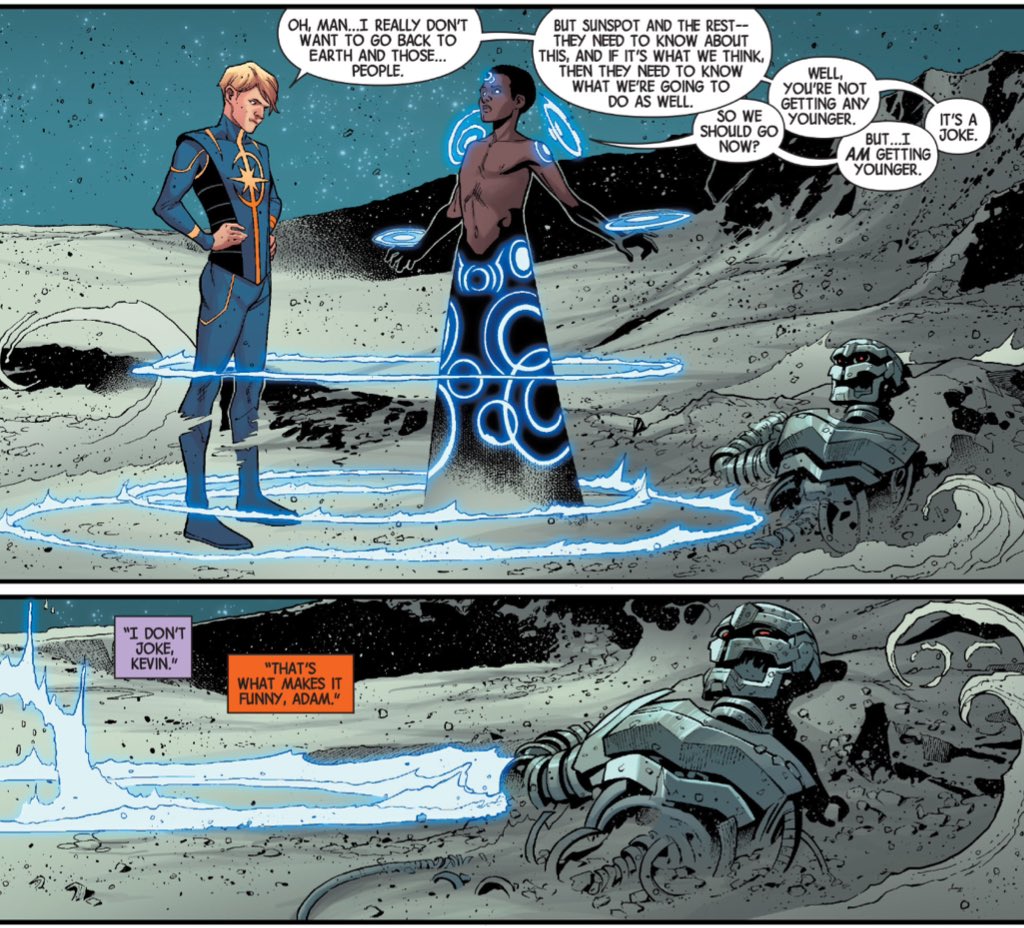

"Now we exist as a perfect idea."

Hickman once again hints that the key arc of his "Avengers" is that of creations moving beyond their creators.

Very relevant for an epic superhero comic book event.

(Avengers #33.)

Hickman once again hints that the key arc of his "Avengers" is that of creations moving beyond their creators.

Very relevant for an epic superhero comic book event.

(Avengers #33.)

Hickman's "Avengers" run really does synthesise a lot of Marvel history, even before the reader gets to "Battleworld", it feels like the characters are navigating an obstacle course of their own history.

Civil War. The Illuminati. Here, "Avengers Forever."

(Avengers #34.)

Civil War. The Illuminati. Here, "Avengers Forever."

(Avengers #34.)

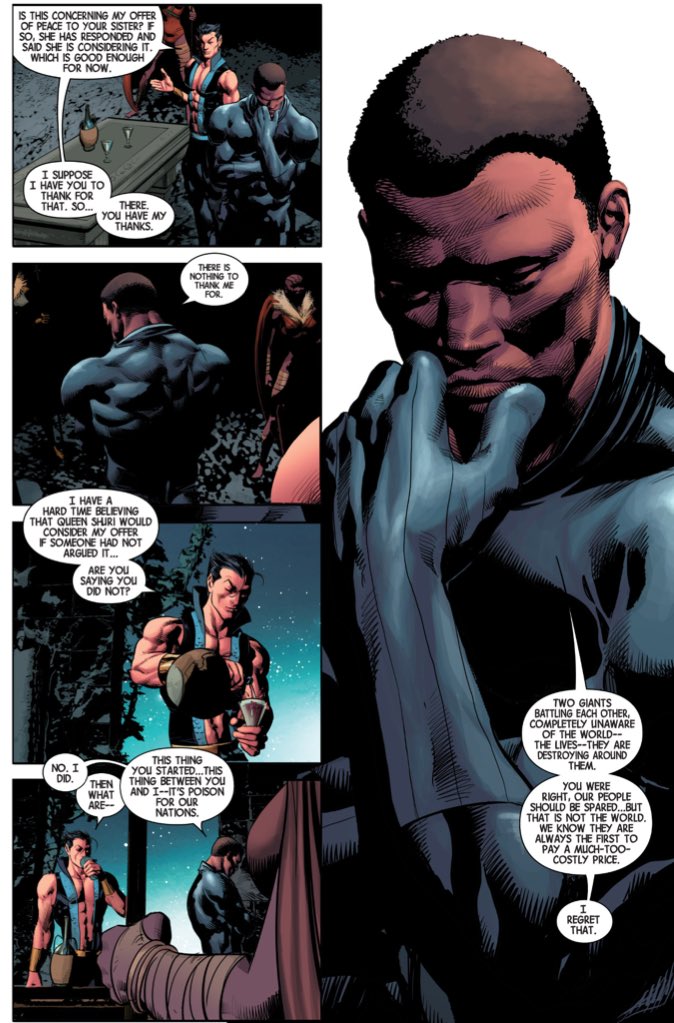

"You are a good man. With a good heart. But it is hard for a good man to be a king."

I understand why Coogler avoided this characterisation, but it is a shame that "Black Panther" glossed over the weight and compromise that defined Hickman and Coates' work on T'Challa.

(NA #18)

I understand why Coogler avoided this characterisation, but it is a shame that "Black Panther" glossed over the weight and compromise that defined Hickman and Coates' work on T'Challa.

(NA #18)

In their work on Black Panther, Hickman and Coates suggest that it is sometimes impossible to be both "a good man" and "a good king."

Sometimes kings do terrible things for their kingdoms.

Hickman's "New Avengers" is one of the great Black Panther stories.

(New Avengers #18.)

Sometimes kings do terrible things for their kingdoms.

Hickman's "New Avengers" is one of the great Black Panther stories.

(New Avengers #18.)

Even before "Battleworld", Hickman acknowledges that the Marvel Universe is divided into kingdoms and fiefdoms, powers and principalities, thrones and dominions.

Hickman's story is about the price of such divisions, the cost such of short-sighted decisions.

(New Avengers #18.)

Hickman's story is about the price of such divisions, the cost such of short-sighted decisions.

(New Avengers #18.)

A persistent criticism of Hickman's run is that it is not a Marvel story.

However, it is insanely specifically a Marvel story. It's a story only possible within the Marvel Universe, with those kingdoms and thrones.

It's a story of kings trying to be gods.

(New Avengers #18.)

However, it is insanely specifically a Marvel story. It's a story only possible within the Marvel Universe, with those kingdoms and thrones.

It's a story of kings trying to be gods.

(New Avengers #18.)

It's telling, for example that this conversation comes right before Hickman throws the New Avengers into combat with the Great Society.

Embracing the idea of "Marvel's Crisis on Infinite Earths", the Great Society are pretty overtly Justice League analogues.

(New Avengers #19.)

Embracing the idea of "Marvel's Crisis on Infinite Earths", the Great Society are pretty overtly Justice League analogues.

(New Avengers #19.)

It's simplistic to argue that the DC "pantheon" is comprised of gods & archetypes while the Marvel stable is populated by kings & scientists. But there's some truth in it.

Hickman throws these two models in opposition, in the ultimate "red skies" crossover.

(New Avengers #19.)

Hickman throws these two models in opposition, in the ultimate "red skies" crossover.

(New Avengers #19.)

To be fair to Hickman, he is careful to populate his epic with small character-centric moments for even marginal players who are in use in other sections of the shared Marvel Universe.

Here, a small moment with Hank McCoy and Bruce Banner.

(New Avengers #19.)

Here, a small moment with Hank McCoy and Bruce Banner.

(New Avengers #19.)

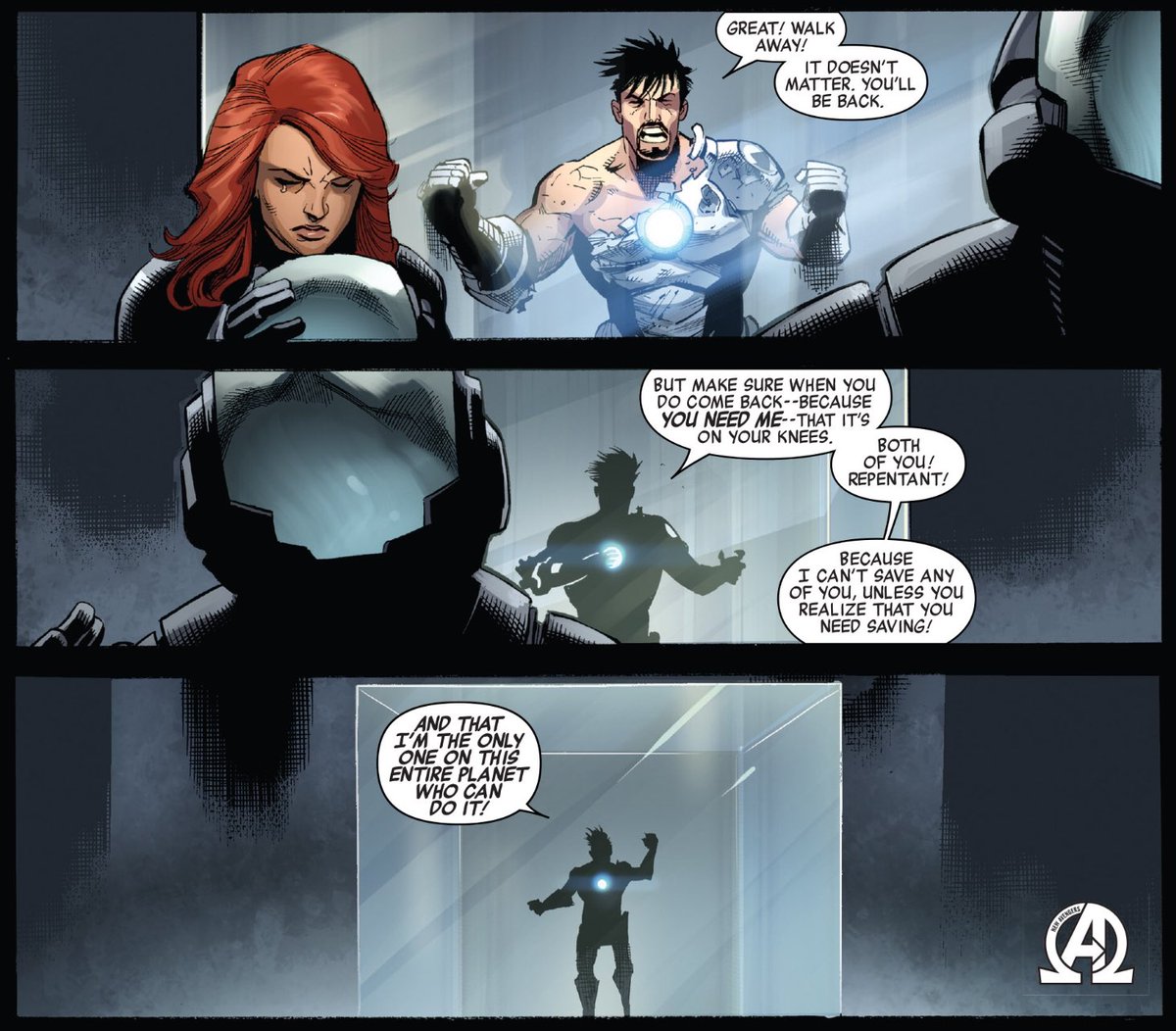

Even the characters who exist on the perephery of Hickman's narrative by necessity, their fate dictated by other editorial whims, are still given clear motivations in Hickman's epic.

Here, the tragedy of Tony Stark.

(New Avengers #18.)

Here, the tragedy of Tony Stark.

(New Avengers #18.)

And here a short scene with Reed Richards.

Richards is an interesting case. Although technically being written by Matt Fraction and James Robinson for most of Hickman's "Avengers" run, he's the protagonist of Hickman's two stories that bookend the saga.

(New Avengers#19.)

Richards is an interesting case. Although technically being written by Matt Fraction and James Robinson for most of Hickman's "Avengers" run, he's the protagonist of Hickman's two stories that bookend the saga.

(New Avengers#19.)

For all that Hickman's run is criticised for not "really" being an Avengers book, it's an Avengers book in arguably the most central way.

It's core characters, the ones with clear and uninterrupted arcs within the book, are those orphaned by editorial.

(New Avengers #19.)

It's core characters, the ones with clear and uninterrupted arcs within the book, are those orphaned by editorial.

(New Avengers #19.)

The central characters of Hickman's run are those without ongoing titles being penned by other writers.

So, Strange, N amor, T'Challa.

Those are the three characters with the clearest and most contained arcs under Hickman's pen.

(New Avengers #19.)

So, Strange, N amor, T'Challa.

Those are the three characters with the clearest and most contained arcs under Hickman's pen.

(New Avengers #19.)

It's a great example of Hickman working within the confines of monthly comics, understanding other characters are beholden to the arcs overseen by other writers.

It's clever, pragmatic plotting.

It's also why the eight-month time skip in "Time Runs Out" is so clever.

(NA #19.)

It's clever, pragmatic plotting.

It's also why the eight-month time skip in "Time Runs Out" is so clever.

(NA #19.)

Historically, the difference between "Justice League" and "Avengers" is the manner in which "Avengers" kinda becomes an island of misfit toys.

A home for characters without any other monthly books to tell their stories, develop their arcs; Hank Pym, T'Challa, Hawkeye.

(NA #20.)

A home for characters without any other monthly books to tell their stories, develop their arcs; Hank Pym, T'Challa, Hawkeye.

(NA #20.)

So Hickman works with characters who didn't have on-going solo titles overlapping with his work. Doctor Strange could literally sell his soul here, for example.

I wonder if Hickman requested them for his run, or simply worked with what was available to him.

(New Avengers #20.)

I wonder if Hickman requested them for his run, or simply worked with what was available to him.

(New Avengers #20.)

Nice dramatic irony here, reinforcing a big theme of the story.

Strange tries to sell his soul for power to protect the planet, only to discover his soul is not good currency.

However, what Strange is trying to achieve is tainted by his method of trying to achieve it.

(NA #20)

Strange tries to sell his soul for power to protect the planet, only to discover his soul is not good currency.

However, what Strange is trying to achieve is tainted by his method of trying to achieve it.

(NA #20)

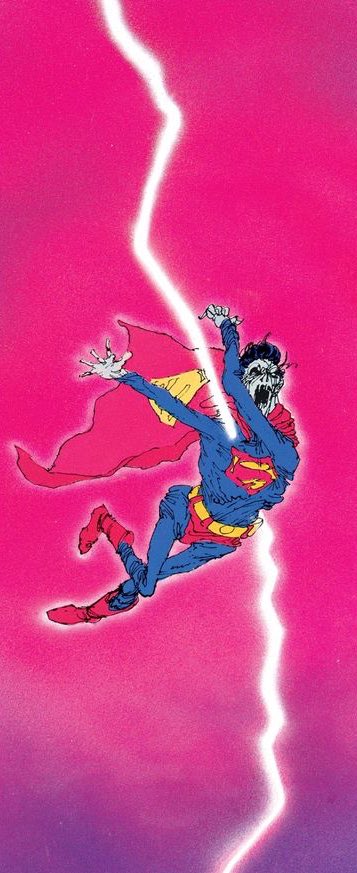

Another nice DC homage, this time to "The Dark Knight Returns."

Nice touch, given how the title lines up chronologically with "Crisis on Infinite Earths" and the original "Secret Wars", and its thematic relevance to the story being told.

(New Avengers #21.)

Nice touch, given how the title lines up chronologically with "Crisis on Infinite Earths" and the original "Secret Wars", and its thematic relevance to the story being told.

(New Avengers #21.)

There's a sense that Hickman deals more effectively (albeit fleetingly) with the deconstruction of superheroes in "Avengers" than Spencer did when he took it as the core thesis of "Secret Empire."

Superheroes are power fantasies, but isn't power terrifying?

(New Avengers #22.)

Superheroes are power fantasies, but isn't power terrifying?

(New Avengers #22.)

Another nice, small example of Hickman's influence on the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

(New Avengers #22.)

(New Avengers #22.)

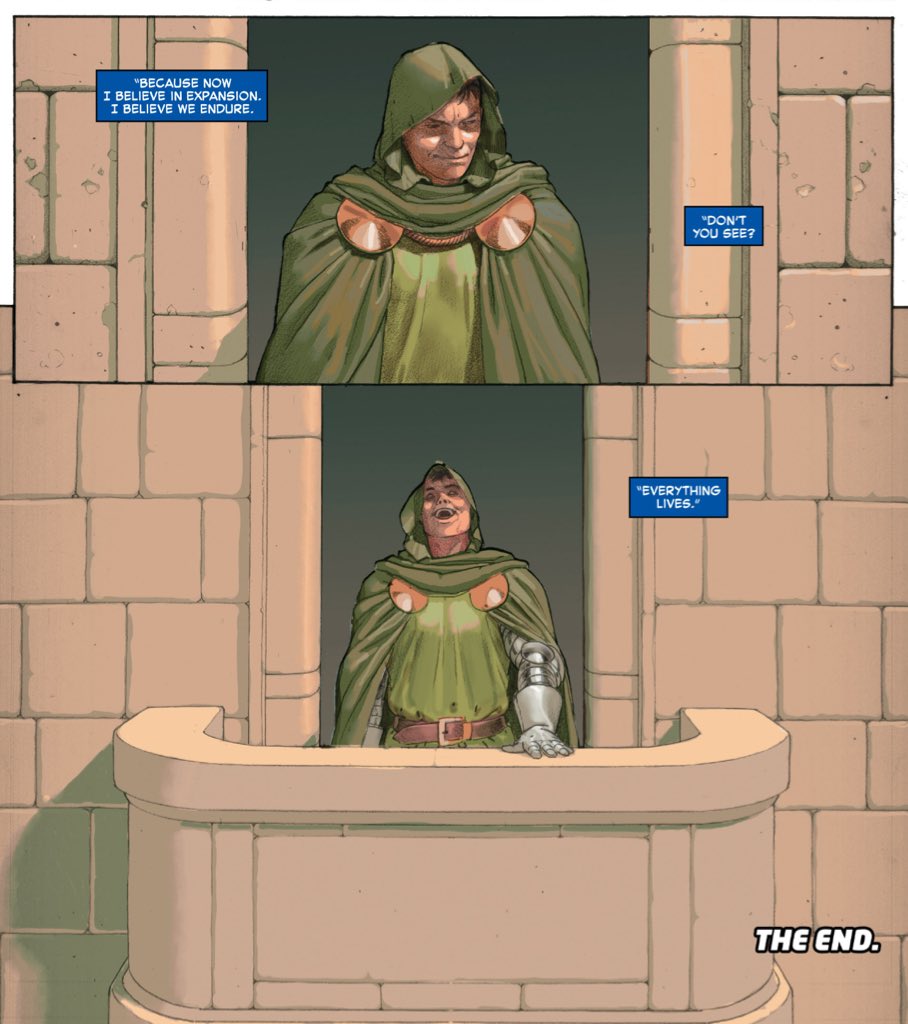

"... so the people can sleep at night..."

Nice set-up/call-back from Hickman.

Also, "... in Latveria, Doom demands that children always get a good night's sleep" is just the perfect line for Doctor Doom. Camp, but he really, truly means it.

(New Avengers #21/23.)

Nice set-up/call-back from Hickman.

Also, "... in Latveria, Doom demands that children always get a good night's sleep" is just the perfect line for Doctor Doom. Camp, but he really, truly means it.

(New Avengers #21/23.)

Just in case Hickman's "New Avengers" should be confused with a "darker and edgier" title, the last issue before "Time Runs Out" explicitly has a bunch of kids telling of their elders for the sins committed in their name.

(New Avengers #23.)

(New Avengers #23.)

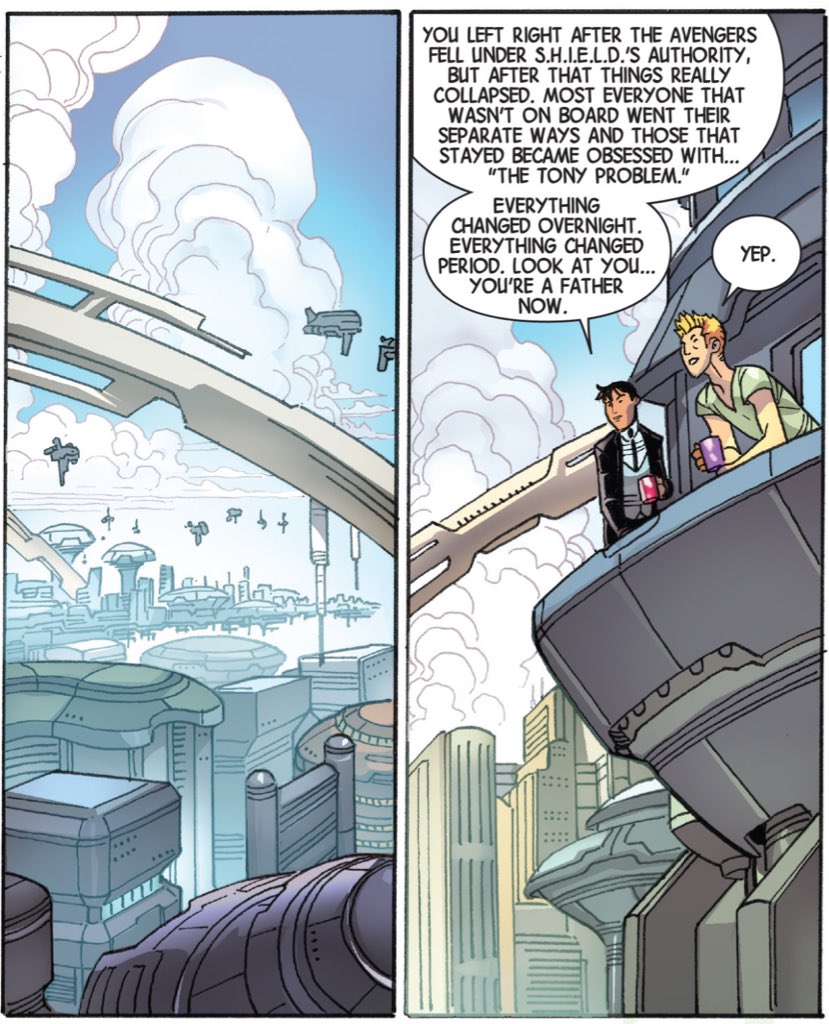

The eight month time jump into "Time Runs Out" is another pragmatic narrative choice.

It allows Hickman to effectively take complete control of every facet of the Marvel Universe that he needs, without disrupting the flow of other writers on other books.

(Avengers #35.)

It allows Hickman to effectively take complete control of every facet of the Marvel Universe that he needs, without disrupting the flow of other writers on other books.

(Avengers #35.)

Hickman cannily uses developments in other books - Thor becoming "unworthy" in Aaron's "Thor", Steve ageing in Remender's "Captain America", Tony going evil in Taylor's "Superior Iron Man" - to sell the idea that things have actually changed over the time skip.

(Avengers #35.)

(Avengers #35.)

After all, characters in superhero comics tend be "stuck" in time.

Putting all this change in a time skip, Hickman emphasises the movement of time within his narrative for these characters.

Even if you aren't reading the other books, you know things've changed.

(Avengers #35)

Putting all this change in a time skip, Hickman emphasises the movement of time within his narrative for these characters.

Even if you aren't reading the other books, you know things've changed.

(Avengers #35)

Even acknowledging the passage of time as overtly as Hickman does in "Time Runs Out", allowing it to take its toll on the characters in the narrative suggests that the Marvel Universe is "broken", that the stasis has been shattered.

(Avengers #35.)

(Avengers #35.)

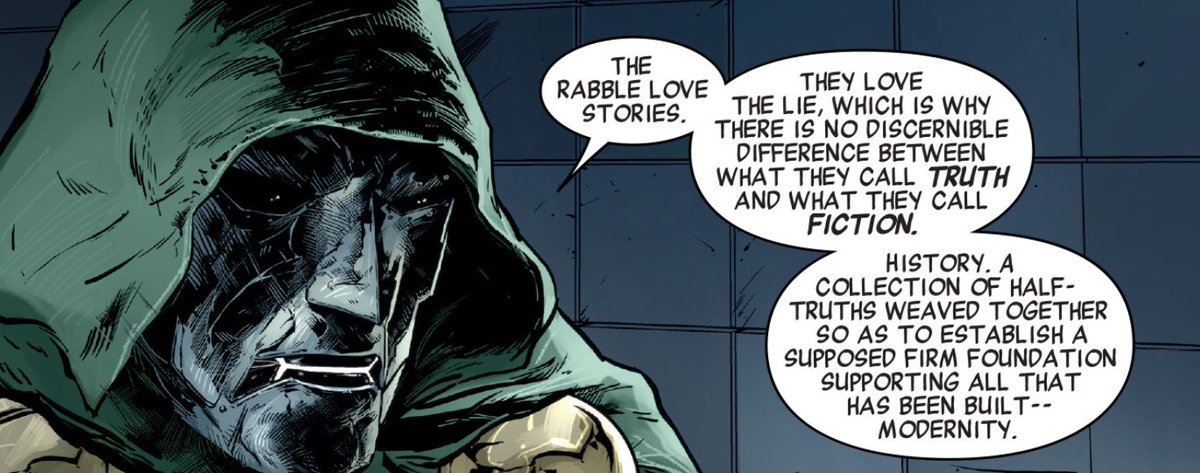

I believe that Abraham Reisman pointed to Hickman's interpretation of Victor Von Doom as one of the reasons that Doom is the best supervillain in the Marvel Universe.

This scene in particular.

"Doom is no man's second choice."

http://www.vulture.com/2017/06/why-marvels-doctor-doom-is-the-best-supervillain.html

(New Avengers #24.)

This scene in particular.

"Doom is no man's second choice."

http://www.vulture.com/2017/06/why-marvels-doctor-doom-is-the-best-supervillain.html

(New Avengers #24.)

Interestingly, you could argue that Hickman only really got away with telling this story with these characters because they were b-listers.

I'm reading comments from Black Panther fans up in arms over Hickman's characterisation at the time, for example.

(New Avengers #24.)

I'm reading comments from Black Panther fans up in arms over Hickman's characterisation at the time, for example.

(New Avengers #24.)

Nobody really cared about the outrage of Black Panther fans in 2012-2015, because there were a few dozen of them.

If Hickman tried to add this level of complexity to Black Panther after the film, there'd be "Secret Empire" level internet outrage.

(New Avengers #24.)

If Hickman tried to add this level of complexity to Black Panther after the film, there'd be "Secret Empire" level internet outrage.

(New Avengers #24.)

For some reason, "bearded, dishevelled Reed Richards on the run paying for his sins" always reminded me of "bearded, dishevelled Walter White on the run paying for his sins."

Given Hickman's other nods to prestige television, I'm not sure it's a coincidence.

(New Avengers #25.)

Given Hickman's other nods to prestige television, I'm not sure it's a coincidence.

(New Avengers #25.)

One of the stronger criticism of Hickman's "Avengers" is that it's a shaggy dog tale, seventy-seven issues of Tony Stark failing to prevent the end of the world.

This is fair, but it also lends the story the air of grand tragedy.

(New Avengers #26.)

This is fair, but it also lends the story the air of grand tragedy.

(New Avengers #26.)

There's undoubtedly a "meta" self-aware aspect to this shaggy dog tale.

Particularly in Hickman's use of the X-Men, which consciously marginalises them in terms of the shared Marvel Universe, playing on their position in the multimedia hierarchy.

(Avengers #38/Secret Wars #4.)

Particularly in Hickman's use of the X-Men, which consciously marginalises them in terms of the shared Marvel Universe, playing on their position in the multimedia hierarchy.

(Avengers #38/Secret Wars #4.)

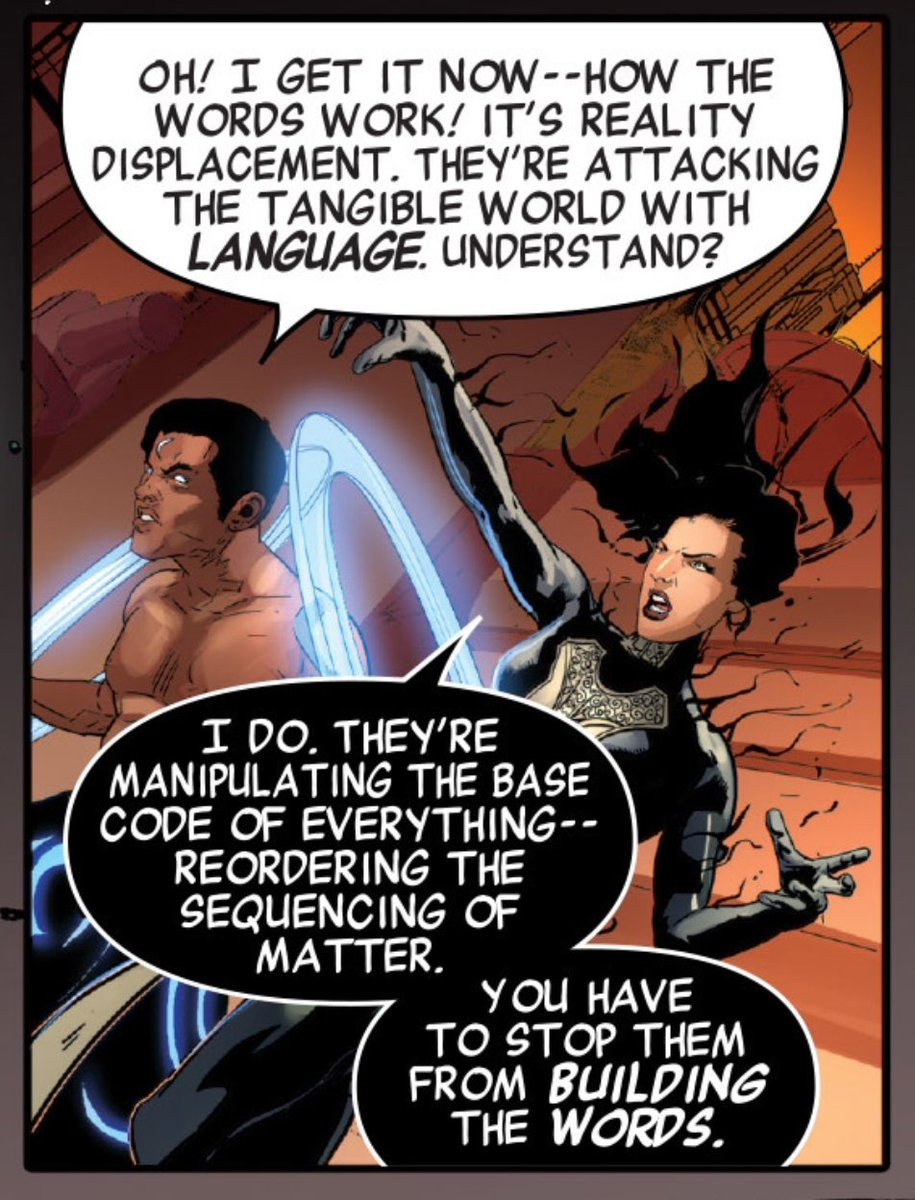

Speaking of the meta-textual elements of Hickman's run, were we get the use of words to alter reality and the argument that fiction and truth are indistinguishable.

Appropriate sentiments for characters trapped in a story.

(New Avengers #27.)

Appropriate sentiments for characters trapped in a story.

(New Avengers #27.)

Worth noting Hickman starts layering in these self-aware plot elements around the same time that his introduces The Beyonders into play.

The Beyonders have long been seen as stand-ins for Marvel editorial, all-powerful beings shaping the Marvel Universe.

http://www.supermegamonkey.net/chronocomic/entries/secret_wars_ii_1.shtml

The Beyonders have long been seen as stand-ins for Marvel editorial, all-powerful beings shaping the Marvel Universe.

http://www.supermegamonkey.net/chronocomic/entries/secret_wars_ii_1.shtml

Continuing the meta text of Hickman's "Avengers", which becomes more pronounced once the Beyonders come into play.

Here, discussing the Ultimate Universe, largely considered inert by 2015.

(Avengers #41.)

Here, discussing the Ultimate Universe, largely considered inert by 2015.

(Avengers #41.)

Ironically, Hickman's first scene in the Ultimate Universe consciously riffs on "The Winter Soldier", alluding to another Marvel Universe perhaps equidistant between the two last surviving Marvel universes.

"Gonna stop a lot of threats before they happen..."

(Avengers #41.)

"Gonna stop a lot of threats before they happen..."

(Avengers #41.)

Reinforcing the idea of the Beyonders as the writers and editors of the Marvel Universe, it's telling that they catalogue the multiverse using "the library of worlds."

(New Avengers #33.)

(New Avengers #33.)

Even as Hickman reveals the grand mechanics of his plot, he seeds smaller mysterious.

For example, the implication that some of Doom's "black swans" are versions of familiar heroes.

Here, Ilyana Rasputin, Lady Deadpool, mohawk Storm.

(New Avengers #33.)

For example, the implication that some of Doom's "black swans" are versions of familiar heroes.

Here, Ilyana Rasputin, Lady Deadpool, mohawk Storm.

(New Avengers #33.)

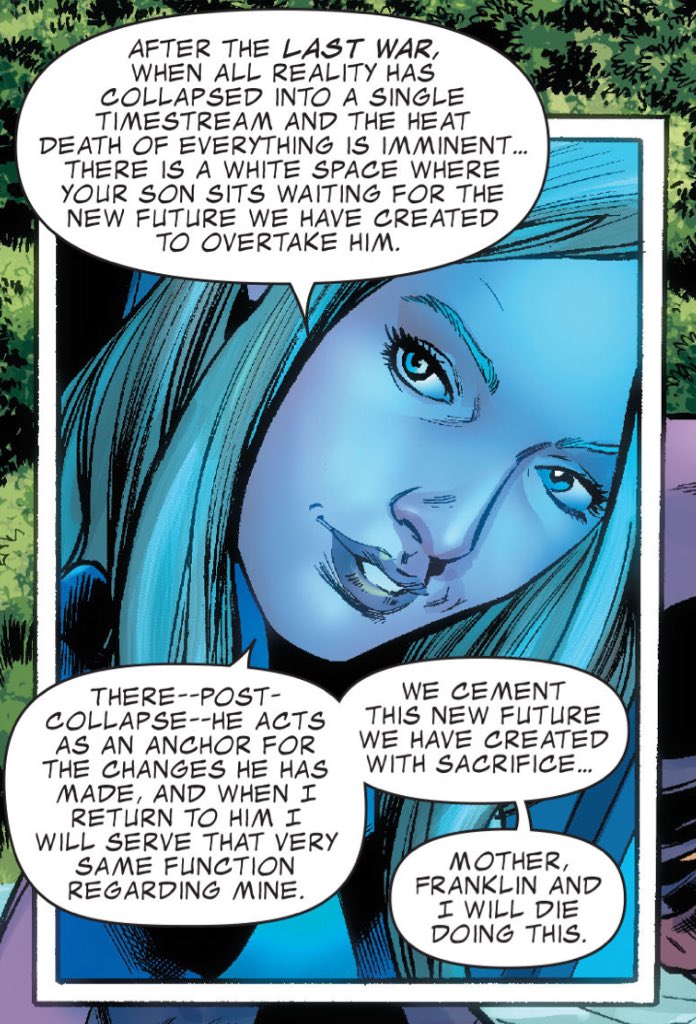

For example, some fans speculate that the black swan who drives the plot of "New Avengers" is an alternate Valeria Richards.

It's never confirmed in text, but it adds a lot of subtext to Reed Richards' interactions with both the black swan and Valeria over the arc.

(NA #33.)

It's never confirmed in text, but it adds a lot of subtext to Reed Richards' interactions with both the black swan and Valeria over the arc.

(NA #33.)

I believe it was @DavidUzumeri who argued that the meta fictional natural of the Beyonders power and manipulation of the narrative is denoted by a sketchier crosshatched art style when that power is used in the narrative.

It looks like a sketch, a rough draft.

(Secret Wars #1.)

It looks like a sketch, a rough draft.

(Secret Wars #1.)

Also, this is possibly the best cameo that the Punisher has ever made in an event comic book.

Much better than, say, "Secret Empire."

(Secret Wars #1.)

Much better than, say, "Secret Empire."

(Secret Wars #1.)

Hickman presents the collision of two worlds as the opposite of cells dividing, even in the imagery. Death as the reverse of life.

An "inversion" if you will.

(Secret Wars #1.)

An "inversion" if you will.

(Secret Wars #1.)

As an aside, with the release of “Infinity War” today, I was thinking about Jonathan Hickman’s run.

Honestly? I find the MCU Avengers in both “Civil War” and “Infinity War” much more like cogs in an inhuman machine than the literal “Avengers machine” featured in Hickman’s work.

Honestly? I find the MCU Avengers in both “Civil War” and “Infinity War” much more like cogs in an inhuman machine than the literal “Avengers machine” featured in Hickman’s work.

One of those great "... if the black swan is Valaria, this sequence becomes a lot more loaded" scenes.

(Secret Wars #6.)

(Secret Wars #6.)

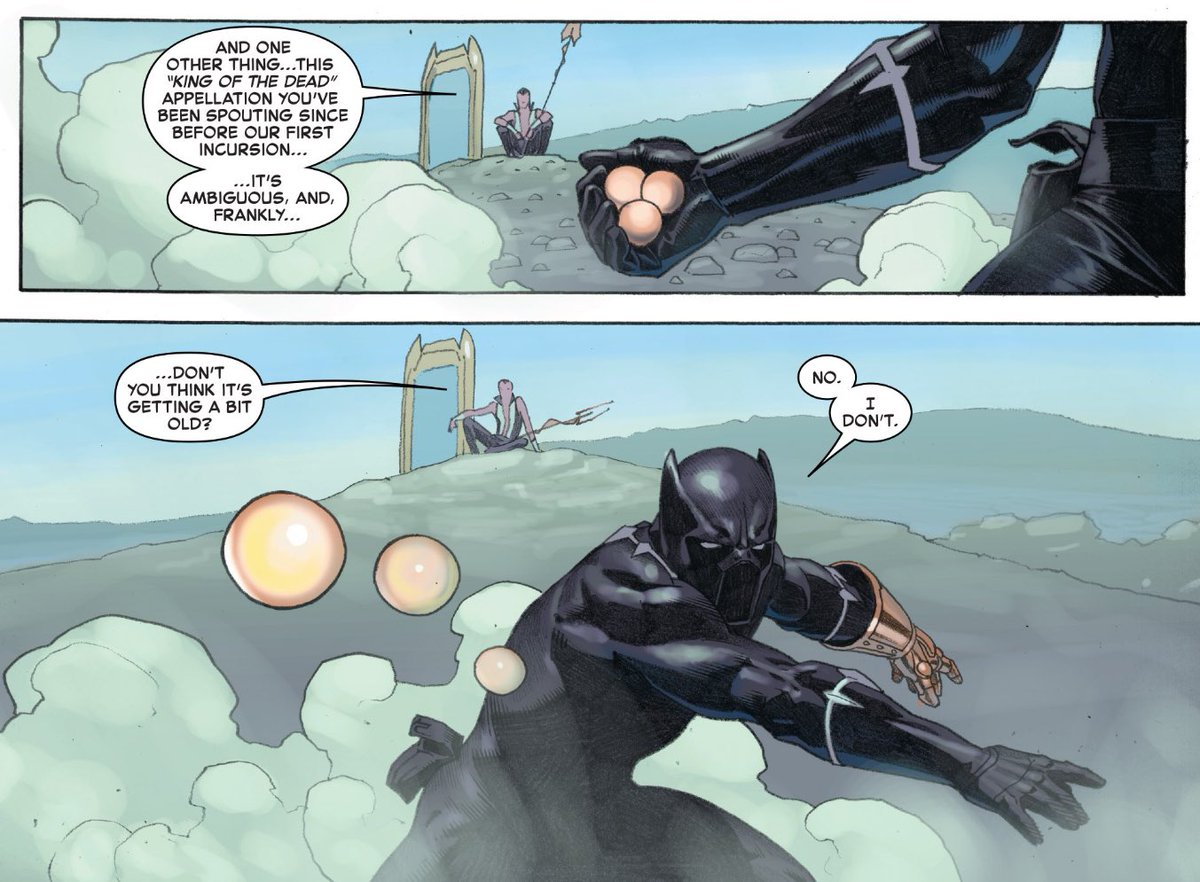

One of the really great extended set-up-and-pay-off bits from Hickman's run, having set up T'Challa as "King of the Dead" during his "Fantastic Four" run more than three years earlier.

(Secret Wars #7.)

(Secret Wars #7.)

"Um, Victor, they're declaring MCU Thanos in #InfinityWar as one of the best Marvel villains ever..."

(Secret Wars #8.)

(Secret Wars #8.)

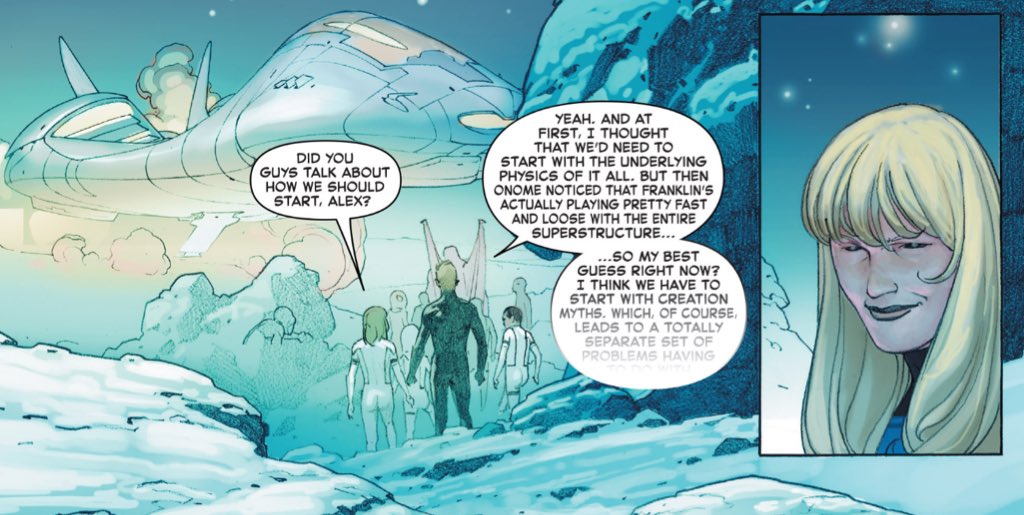

"Did you guys talk about how we should start, Alex?"

"I think we should start with creation myths."

Of course Hickman's epic circles back to the Fantastic Four, effectively the Marvel Universe's "creation myth."

(Secret Wars #9.)

"I think we should start with creation myths."

Of course Hickman's epic circles back to the Fantastic Four, effectively the Marvel Universe's "creation myth."

(Secret Wars #9.)

Binging Hickman's "Avengers" brought me back to his "Fantastic Four."

And it's amazing how many ideas are there from the "Dark Reign" miniseries; notably the idea of children creating in a world their father created for them.

(Dark Reign: Fantastic Four #1.)

And it's amazing how many ideas are there from the "Dark Reign" miniseries; notably the idea of children creating in a world their father created for them.

(Dark Reign: Fantastic Four #1.)

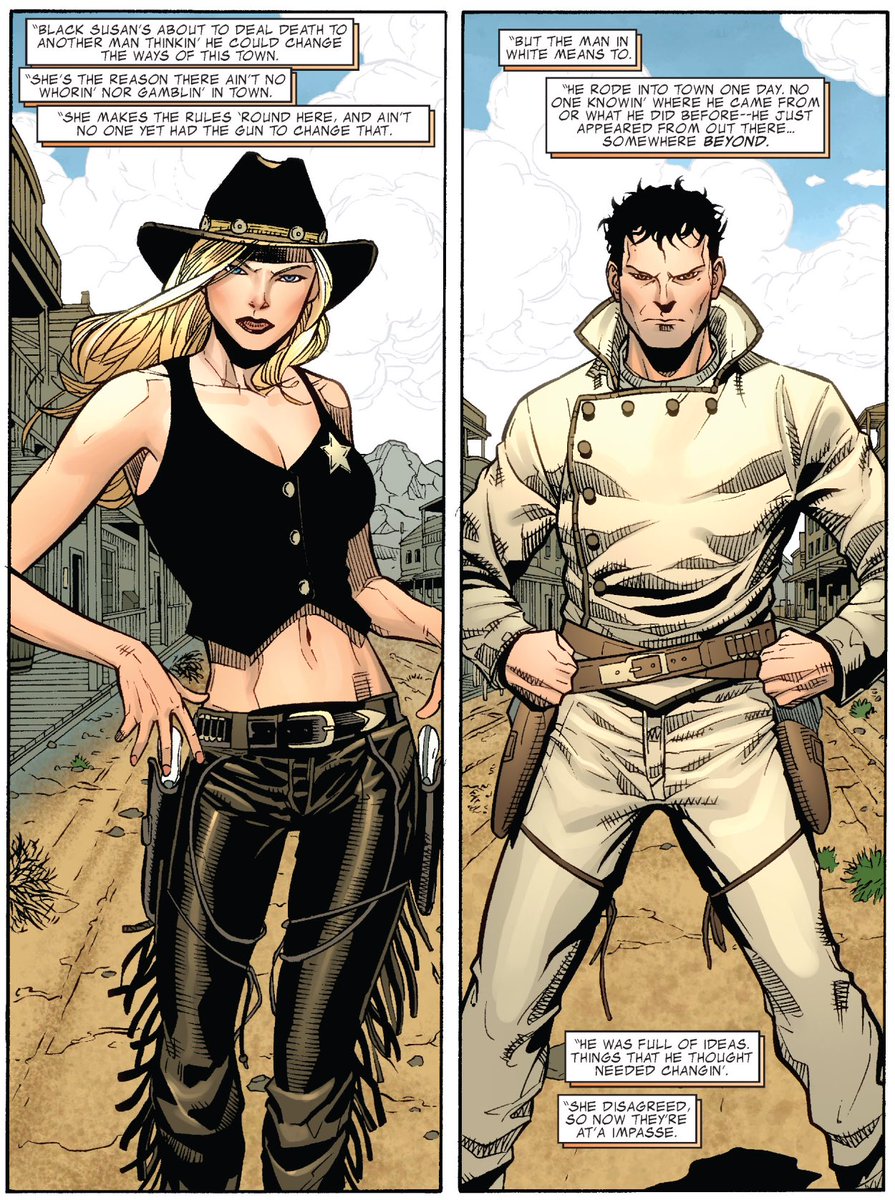

You could (at a stretch) argue that "Dark Reign: Fantastic Four" prefigures "Secret Wars" by having multiple iterations of characters traverse multiple worlds within the confines of a single space.

(Yes, the pirates are a Lee/Kirby shoutout.)

(Dark Reign: Fantastic Four #2.)

(Yes, the pirates are a Lee/Kirby shoutout.)

(Dark Reign: Fantastic Four #2.)

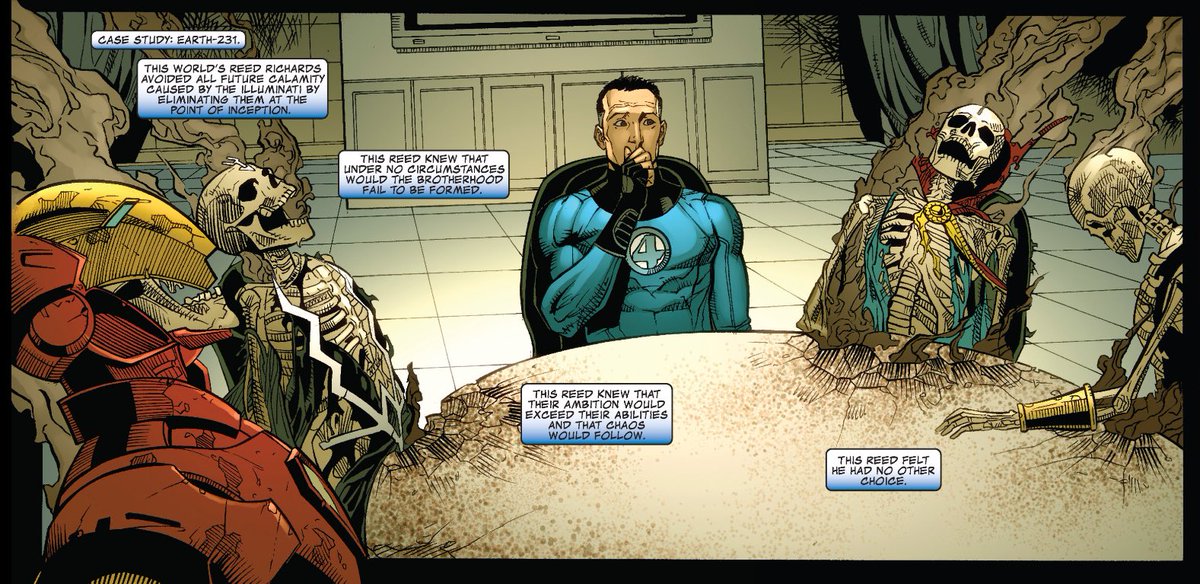

There are other foreshadowing of Hickman's later "New Avengers" work:

(a.) the Illuminati;

(b.) the acknowledgment that the Illuminati are a bad idea;

(c.) oh, hey, out of nowhere, it's the Beyonder!

(Dark Reign: Fantastic Four #3.)

(a.) the Illuminati;

(b.) the acknowledgment that the Illuminati are a bad idea;

(c.) oh, hey, out of nowhere, it's the Beyonder!

(Dark Reign: Fantastic Four #3.)

Another nice recurring Hickman motif.

The "Council of Reeds" gathering and stockpiling Doom from across the multiverse evokes Doom's later use of the Black Swans to gather and stockpile Molecule Man from across the multiverse.

(Fantastic Four #571/Secret Wars #5.)

The "Council of Reeds" gathering and stockpiling Doom from across the multiverse evokes Doom's later use of the Black Swans to gather and stockpile Molecule Man from across the multiverse.

(Fantastic Four #571/Secret Wars #5.)

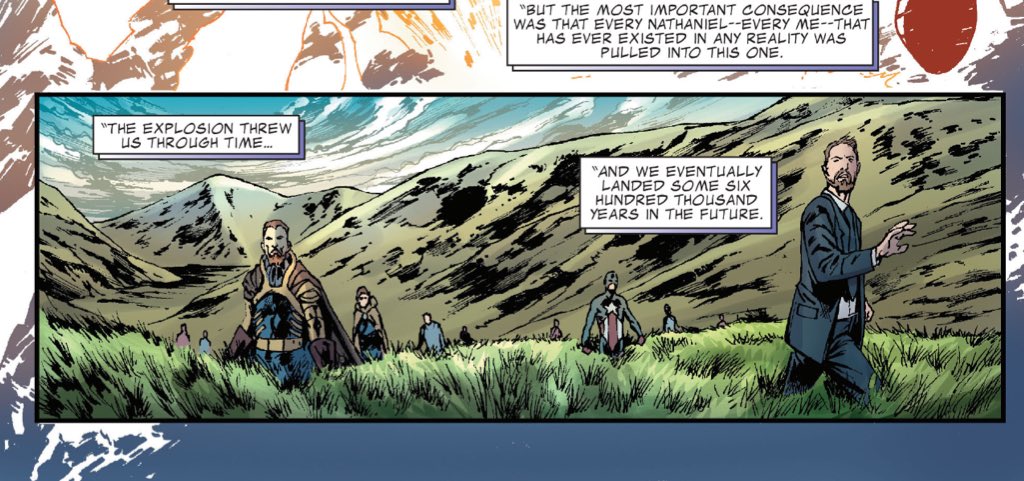

More future echoes in Hockman's "Fantastic Four."

Here, all Nathaniel Richards compressed into a single reality, like "Battleworld."

But also forced to destroy each other so one might live, like the "Incursions."

(Fantastic Four #581.)

Here, all Nathaniel Richards compressed into a single reality, like "Battleworld."

But also forced to destroy each other so one might live, like the "Incursions."

(Fantastic Four #581.)

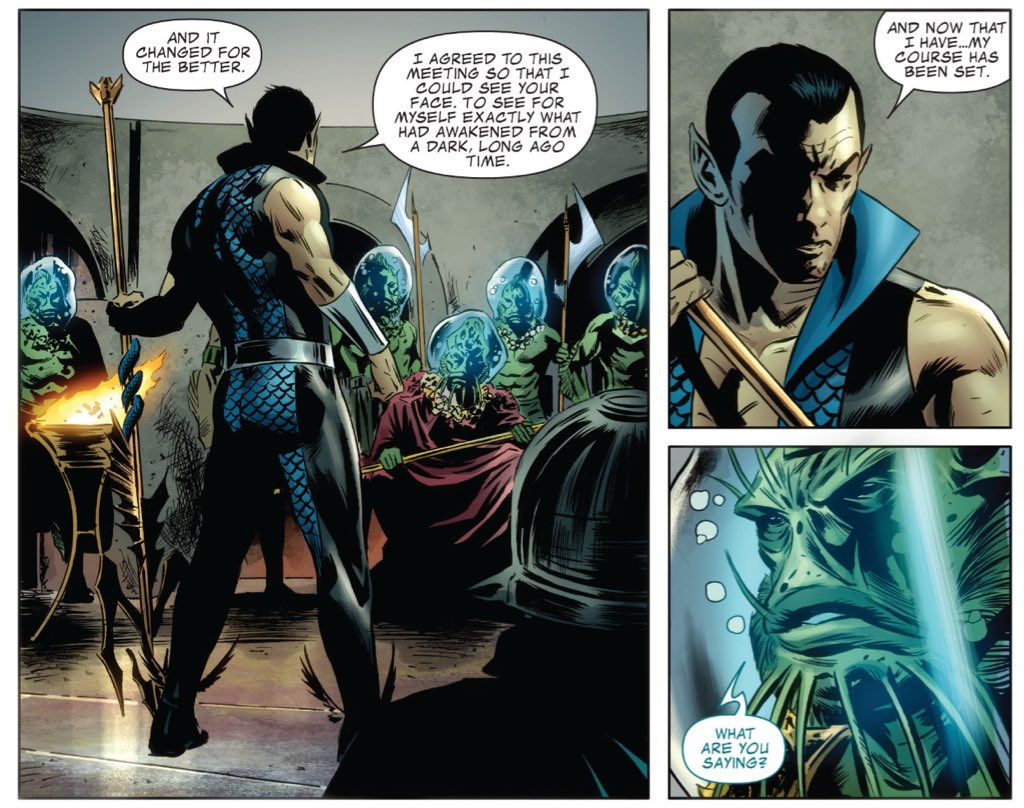

Classic Namor.

Hickman even preserves the rhythm of the sequence, building slowly to the page turn and then... trident!

(Fantastic Four #585/New Avengers #19.)

Hickman even preserves the rhythm of the sequence, building slowly to the page turn and then... trident!

(Fantastic Four #585/New Avengers #19.)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter