It can be difficult to explain how normal faults shape mountains (as opposed to just basins), so my niece, my sister @Artprof4 and I made one in a tank today (short

).

).

).

).

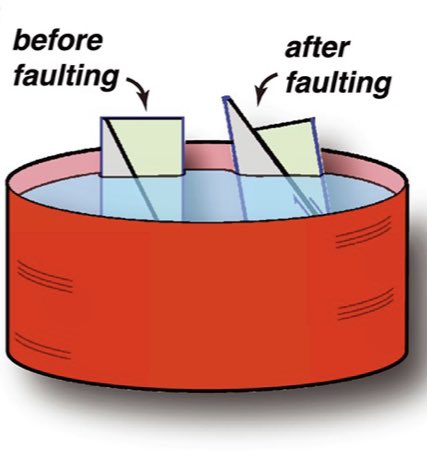

We  a fault between 2 plates made of flexible foam and glued magnets on both ends so the fault would only slide (and not open)

a fault between 2 plates made of flexible foam and glued magnets on both ends so the fault would only slide (and not open)

a fault between 2 plates made of flexible foam and glued magnets on both ends so the fault would only slide (and not open)

a fault between 2 plates made of flexible foam and glued magnets on both ends so the fault would only slide (and not open)

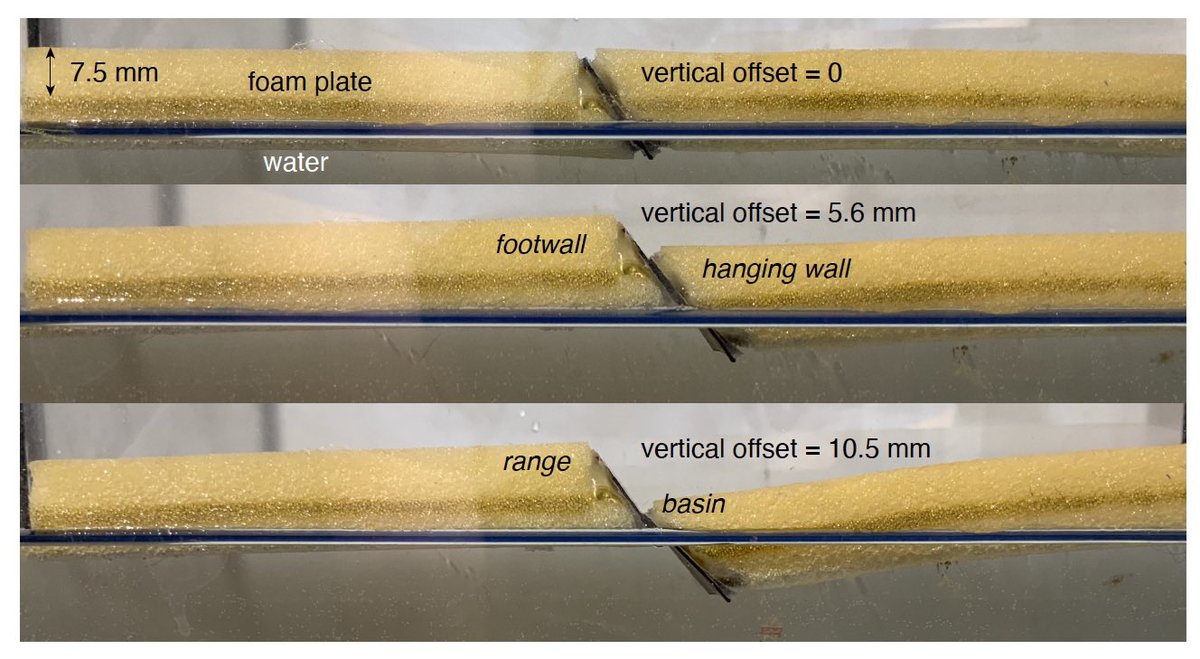

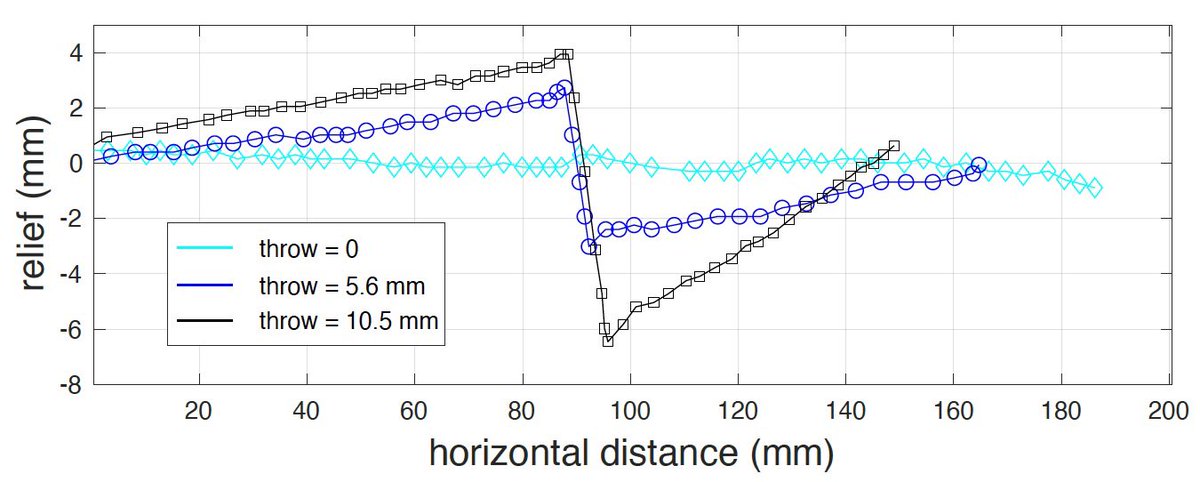

Here are 3 snapshots showing increasing fault offsets. Left block moves  , right block moves

, right block moves  . Far from the fault they just move

. Far from the fault they just move  and

and  . This forces the plates to bend upward, against gravity - and downward, against buoyancy.

. This forces the plates to bend upward, against gravity - and downward, against buoyancy.

, right block moves

, right block moves  . Far from the fault they just move

. Far from the fault they just move  and

and  . This forces the plates to bend upward, against gravity - and downward, against buoyancy.

. This forces the plates to bend upward, against gravity - and downward, against buoyancy.

Because of this flexure, elevation doesn’t drop everywhere in our foam rift, and a majestic 4-mm high fault-bounded range is formed.

For a detailed overview of this process, see for example Thompson & Parsons 2016, whose Fig. 3C very much inspired us https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2015JB012240

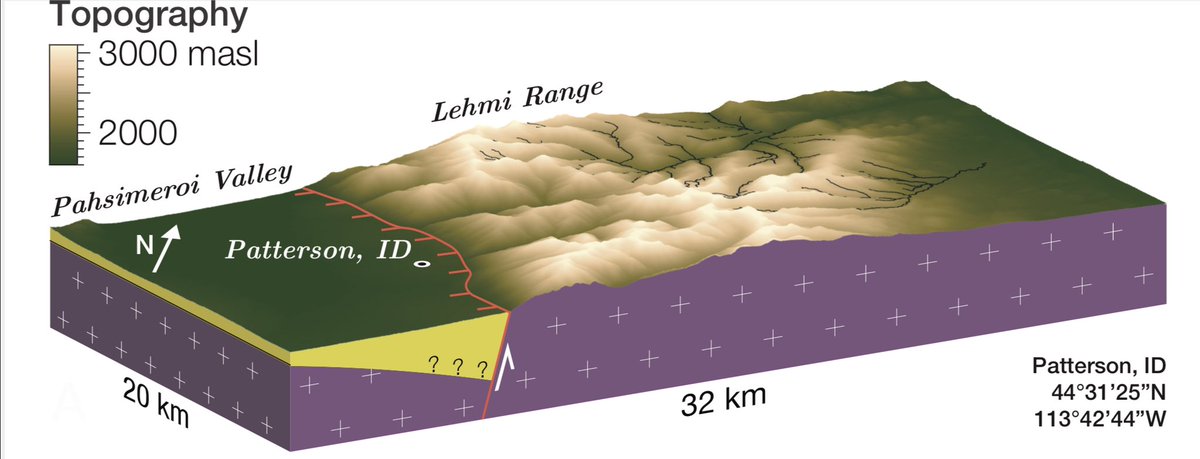

Of course in the real world, the mountain is made up of brittle upper crust floating atop weak (viscous) lower crust. Also, it gets incised by rivers / glaciers as the basin gets filled with sediments, like in the Lemhi Range in Idaho  (a personal favorite, fig. by @_geoLuca )

(a personal favorite, fig. by @_geoLuca )

(a personal favorite, fig. by @_geoLuca )

(a personal favorite, fig. by @_geoLuca )

Next stop: core complexes in a tank?

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter