A woman and child pictured beside a kitchen range in slum property c 1910. The photograph may have been taken in connection with a scheme to provide poor mothers with milk for their babies.

The following is the story of a practice that we take for granted today; the importance

The following is the story of a practice that we take for granted today; the importance

of milk as a means to reduce infant mortality amongs our weans.

This tale will be told in a few parts and I hope you find this of interest.

In 1892, in the course of a public address in Glasgow, Lord Rosebery—Scottish Liberal Peer and future Prime Minister—drew attention to the

This tale will be told in a few parts and I hope you find this of interest.

In 1892, in the course of a public address in Glasgow, Lord Rosebery—Scottish Liberal Peer and future Prime Minister—drew attention to the

city’s high childhood mortality:

'' There is one form of mortality which appeals to us perhaps more than any other: it is the mortality of children. In Glasgow, more than 43 per cent of all the deaths that occur are of children under five years old. We cannot but feel it a

'' There is one form of mortality which appeals to us perhaps more than any other: it is the mortality of children. In Glasgow, more than 43 per cent of all the deaths that occur are of children under five years old. We cannot but feel it a

deadly reproach on ourselves that nearly half the deaths in this great city should come to these helpless innocents from causes which we cannot say are beyond our control.''

As a former Under-Secretary for Scottish Affairs at the Home Office, Rosebery had long taken a

As a former Under-Secretary for Scottish Affairs at the Home Office, Rosebery had long taken a

paternalist interest in the conditions of the Glasgow working-class. He enjoyed a reputation as a provocative public speaker and it is significant that he chose a platform in Glasgow on which to raise one of the most pressing public health issues of his time. As one of

Britain’s largest and most important urban centres, Glasgow had severe problems of health and housing which were reflected in the high childhood mortality rates to which Rosebery alluded. Childhood and, especially, infant mortality were to remain on the political agenda of

the city, and the nation as a whole, for many years.

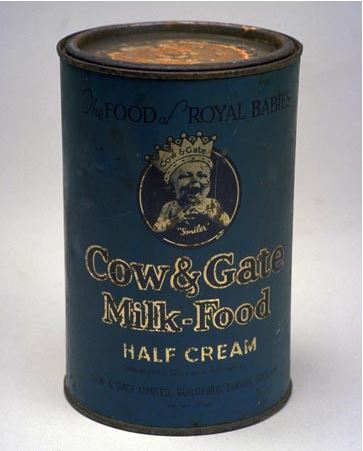

In the 1880s and 1890s, discussion began to centre on

questions of the diet and feeding of infants and, in particular, on milk. This close focus on milk, its quality and supply, was an expression of the growing importance

In the 1880s and 1890s, discussion began to centre on

questions of the diet and feeding of infants and, in particular, on milk. This close focus on milk, its quality and supply, was an expression of the growing importance

of a medical lobby eager to apply the new sciences of bacteriology and chemical physiology to nutrition and public health.

- more to follow -

- more to follow -

In the same year that Rosebery spoke in Glasgow, Pierre

Budin,at the Charite´ Hospital in Paris, established his first Consultations de Nourissons Two years later, in Fe´ camp in Normandy, Leon Dufour, a physician, opened an infant welfare clinic that became the model for the

Budin,at the Charite´ Hospital in Paris, established his first Consultations de Nourissons Two years later, in Fe´ camp in Normandy, Leon Dufour, a physician, opened an infant welfare clinic that became the model for the

Gouttes de Lait movement. Both clinics aimed to encourage breastfeeding, supplemented with sterilised milk where necessary, and to provide weekly medical care and supervision of infants.

Following the success of Dufour’s initiative, the first British milk depot was set up in St Helens in 1899. Others soon followed—Liverpool, Ashton-under-Lyne and Dunkinfield

in 1901; Battersea in 1902; Leith and Bradford in 1903, and Burnley, Dundee and Glasgow in 1904.

in 1901; Battersea in 1902; Leith and Bradford in 1903, and Burnley, Dundee and Glasgow in 1904.

Given the city’s national significance, the public health measures taken by the Glasgow Corporation were watched with interest elsewhere in Britain. The local leaders of the city’s initiative to improve infant welfare also occupied a prominent position within the national

campaign. The development of Glasgow’s Milk Depot is thus an important, and hitherto largely unexplored,

aspect of the history of the topic, and of infant welfare more generally.

- more later -

aspect of the history of the topic, and of infant welfare more generally.

- more later -

In Glasgow, as elsewhere, the founding of the infant milk depot was a result of an alliance between medical and local political interests.The key roles in this were played by William Fleming Anderson, Chairman of the Glasgow Corporation Health Committee, and Archibald Kerr

Chalmers, the city’s Medical Officer of Health (MOH).

In her important discussion of the English milk depots, Deborah Dwork(An aspect of the history of the infant welfare movement in England 1898–1908 ... Deborah Dwork, MPH, PhD)

In her important discussion of the English milk depots, Deborah Dwork(An aspect of the history of the infant welfare movement in England 1898–1908 ... Deborah Dwork, MPH, PhD)

has argued that their founders had a narrower conception of the purpose of depots than their French counterparts. In Paris, supporting mothers to breastfeed was the central

purpose of the Consultations de Nourissons, and clean milk was supplied only where this was not possible.

purpose of the Consultations de Nourissons, and clean milk was supplied only where this was not possible.

In England, by contrast, Dwork maintains, milk distribution

was seen as the principal, if not the exclusive, purpose. This came to be regarded as a weak foundation and ‘the provision of milk without supervision came to be seen as

having only limited usefulness’. in Glasgow,

was seen as the principal, if not the exclusive, purpose. This came to be regarded as a weak foundation and ‘the provision of milk without supervision came to be seen as

having only limited usefulness’. in Glasgow,

Chalmers, Anderson and their colleagues were aware of the deficiencies of English schemes and that, consequently, the city’s depot was established in the knowledge that it was, through the distribution of milk alone, unlikely to provide a satisfactory solution to

high infant

high infant

mortality. In January 1903, Glasgow Corporation’s Health Committee received a delegation from Liverpool. Alderman Roberts and Councillor Shelmerdine had come to provide their Scottish colleagues with a description of that city’s milk depot scheme. The Health Committee decided

to establish a sub-committee to examine the possibility of providing a similar provision in Glasgow. Four members were appointed: William Anderson, William Bilsland, John Carswell and Archibald Kerr Chalmers. Anderson was a local businessman whose strong temperance views had

led him to stand for the Town Council in 1892.Bilsland was another prominent businessman turned councillor, on his way to becoming Lord Provost. Carswell was a doctor, who had served as a parish medical officer before being elected to the Town Council in 1896. Thus he had

extensive personal experience of the health problems of the urban poor. Chalmers had been Glasgow’s Medical Officer of Health since 1898. Able and energetic, he was anxious to consolidate and extend the successful public health programmes of his distinguished predecessor, James

Burn Russell, whose assistant he had been.

- more to follow -

- more to follow -

In the previous decade, considerable progress had been made in the public health of Glasgow, largely through improvements in housing. That indeed had been the chief

legacy of James Burn Russell. Initiatives were now focusing, locally and nationally, on the health of mothers and

legacy of James Burn Russell. Initiatives were now focusing, locally and nationally, on the health of mothers and

children. It was generally accepted that artificially-fed

babies did less well than those who were breastfed, and that consumption of raw cow’s milk by infants was associated with a higher incidence of summer diarrhoea and alimentary tuberculosis. Nevertheless, while it was

babies did less well than those who were breastfed, and that consumption of raw cow’s milk by infants was associated with a higher incidence of summer diarrhoea and alimentary tuberculosis. Nevertheless, while it was

thought that the provision of sterilised milk to infants whose mothers were unable to suckle them should contribute towards the reduction of infant mortality, depots were also seen as a means of establishing contact

with mothers, educating them and strengthening their sense of

with mothers, educating them and strengthening their sense of

responsibility towards their offspring. Thus the Glasgow scheme was conceived, in large part, as a lure to

bring mothers and infants into contact with those who could monitor and advise. To Anderson, Carswell and Chalmers, the municipal milk depot was as much a means as an end

bring mothers and infants into contact with those who could monitor and advise. To Anderson, Carswell and Chalmers, the municipal milk depot was as much a means as an end

in itself. Further evidence that those who advocated the establishment of a depot in Glasgow were not wholly convinced that, in itself,it constituted a solution, can be

found in a speech Anderson delivered to a conference of municipal representatives a month after the Glasgow

found in a speech Anderson delivered to a conference of municipal representatives a month after the Glasgow

depot was opened. Anderson suggested further, more stringent, measures to be adopted ‘should these proceedings and attempts to reduce our

infant mortality not be successful’. He went on:

infant mortality not be successful’. He went on:

''The municipal preparation and sale of infants’ milk may safely be tried in the first instance... . If it does not do all the good we expect, we know it will, at any rate, preserve many infants at present lost through malnutrition. ''

The Glasgow Milk Depot opened at 68 Osborne Street on 17 June 1904. From its inception until the end of December 1904, 314 infants were seen. Each mother received a leaflet, written by Chalmers, emphasising that the depot was only to be used by infants whose mothers were unable

to breastfeed, and setting out in detail the process

for the collection and preparation of milk. The depot was open from 11 am to 6 pm, six days a week, with two days’ supply being issued on a Saturday. The milk was provided

in baskets containing one day’s supply of bottles.

for the collection and preparation of milk. The depot was open from 11 am to 6 pm, six days a week, with two days’ supply being issued on a Saturday. The milk was provided

in baskets containing one day’s supply of bottles.

Each, in turn, contained a quantity of milk sufficient for one feed. A teat was provided, with strict instructions on how to keep it clean. Information was given on regularity of feeding, how to warm the milk, and what to do with left-overs. Mothers were advised to bring their

child fortnightly to be weighed and instructions given to notify the MOH at the first sign of infectious disease.

.

-more to follow -

.

-more to follow -

The milk was provided at a cost of two pence a day for infants aged up to three months.The Corporation believed this to be cheaper than the price in equivalent

schemes in England and their intention was to minimise any cost disincentive in a city in which average wages were low.

schemes in England and their intention was to minimise any cost disincentive in a city in which average wages were low.

In many instances, milk was provided free of charge, the money to cover these cases coming from ‘various sources’, according to Chalmers’s annual reports. Cost and access issues led to fluctuations in the use of depot milk.

Numbers rose in the early years of the scheme, then

Numbers rose in the early years of the scheme, then

fell when a letter of referral was required from a GP or a medical attendant. Numbers rose again, to between 600

and 700, following the establishment of a Lord Provost’s fund for the relief of distress but halved when this financial support was withdrawn. In the first full year

and 700, following the establishment of a Lord Provost’s fund for the relief of distress but halved when this financial support was withdrawn. In the first full year

of its operation, the Depot recorded an increased demand. The average number of gallons distributed daily rose from 60 in December 1904 to 114 in December 1905. This represented an increase in baskets from 253 per day in December 1904 to 522 at the end of 1905. By this time,

however, arrangements for the distribution of the milk had changed. In addition to being available from Osborne Street, it could now be purchased from a number of distributing dairies.26 In December 1904, two such

outlets were made available, in the Bridgeton and Calton districts

outlets were made available, in the Bridgeton and Calton districts

a further seven distributing dairies had been added. While the number of infants receiving milk directly from the Depot fell from 134 in January 1905 to 57 by December

1905, in the same period the number supplied by the other outlets increased from 119 to 465.

-more to follow -

1905, in the same period the number supplied by the other outlets increased from 119 to 465.

-more to follow -

This change in distribution arrangements made the collection of milk more convenient. However, the growing popularity of the distributing dairies raised problems. The Osborne Street Depot kept a register of all infants who attended, including a record of weight over time. While

the dairies were also expected to collect this nformation, in practice the women who worked in the shops tended to ignore this part of the scheme. Thus the goal of establishing contact with mothers and infants in order to educate the former and monitor the health and growth of

the latter could not be achieved if the majority of those using the milk had no direct connection with the Depot itself. Moreover, if the scheme were to fulfil its intended purpose, it was necessary to know something of the background of recipients. Depot milk was primarily

intended for poor children who were not thriving and whose home circumstances were unhygienic. However, as George McCleary, MOH for Battersea and the moving force behind its own milk depot, acknowledged in his review in 1905, doubt had been voiced as to whether mothers who

utilised depots were, in fact, members of the intended target group. When schemes had been proposed, it had been assumed that mothers who took the trouble to obtain a daily supply would be those who were highly motivated to care for their children. But McCleary conceded that it

was possible the pre-prepared meal-in-a-bottle had proven to be attractive to ‘less industrious housewives’. Attributing faults to working-class mothers and blaming

the poor health of urban children on their shortcomings became an increasingly common theme in public health

the poor health of urban children on their shortcomings became an increasingly common theme in public health

discourse in the early decades of the twentieth century.

The problem that Chalmers had identified was the opposite of that which had vexed McCleary. In Glasgow, milk was not being taken up by feckless mothers, but by those who were providing good care for their babies.

The problem that Chalmers had identified was the opposite of that which had vexed McCleary. In Glasgow, milk was not being taken up by feckless mothers, but by those who were providing good care for their babies.

Concluding that more research was required, Chalmers designed a card to be filled out by the COS visitors. It sought basic information on the health of child and mother, family circumstances, such as the death of siblings, occupation of the father, cleanliness of the house and

reasons for the child being fed on depot milk. On the back of the card, space was provided to keep a register

of the weight of the child and for the visitor to enter further remarks. Chalmers also felt that it was crucial that infants most at risk should be brought to the

of the weight of the child and for the visitor to enter further remarks. Chalmers also felt that it was crucial that infants most at risk should be brought to the

attention of his department. Under Scottish legislation, a birth had to be notified within 21 days. However, in Glasgow, over a third of infant deaths occurred within the first four weeks of life, meaning that often the birth and death of a child were notified simultaneously.

What was needed was a means of achieving early notification of births in those districts whose infant mortality rates demanded special attention. In June 1905, at a meeting attended by Chalmers, the Corporation’s Sub-Committee on Infantile Mortality and Milk Supply passed a

resolution recommending that one shilling be paid to the first person to inform the MOH of a birth occurring within any of the identified poorer districts of the city, provided that this information was received within 48 hours of delivery. This gave Chalmers the opportunity to

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter