Here we investigate memory-related brain activity in patients who have had severe memory difficulties since childhood. The article is available here. I’ve made this thread to explain the research to a lay audience who may see the research on Twitter. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0028393221000397

I work with people with Developmental Amnesia (DA). People with DA have suffered a lack of oxygen to the brain when they were little, often from a traumatic birth or an early medical complication. This can cause damage to the hippocampus, a brain region associated with memory.

What’s particularly fascinating about these people, is not what they can’t do, but what they can do despite the hippocampal injury.

Throughout childhood, patients with DA seem to learn language and general knowledge with ease (e.g. “most dogs are friendly but some dogs bite”) even though they don’t have memory for the particular events of their lives (e.g. "yesterday a dog bit my friend in the park!").

This seems to show that the brain systems responsible for learning general knowledge (known as semantic memory) are separate from the brain systems necessary for remembering specific events (known as episodic memory), although not all scientists agree with this conclusion.

Episodic memory involves binding together particular details of an event, including what happened, when it happened, and where it happened. The hippocampus is thought to be crucial for making these links; linking items (like particular dogs) to contexts (like particular parks)

In the study here, we investigated if there was neural evidence from fMRI that patients with developmental amnesia can make links between items and places in memory, even though the patients cannot recall the events of their past.

Perhaps there is a neural signal that connects the items in memory. That is, when presented with a photo of a particular dog, the brain activity might indicate an association with a certain place, even if the patient can’t remember the details of where they saw the dog before.

To test this, we presented controls and adult patients with DA with word and picture pairs. Each word was presented with a picture of a scene (like a park, a field, or a city street) or a scrambled scene where the pixels had been shuffled.

The scene images were chosen because we would expect to see activation in scene-specific areas of the brain when people remember these pictures. The scrambled scenes were a control condition.

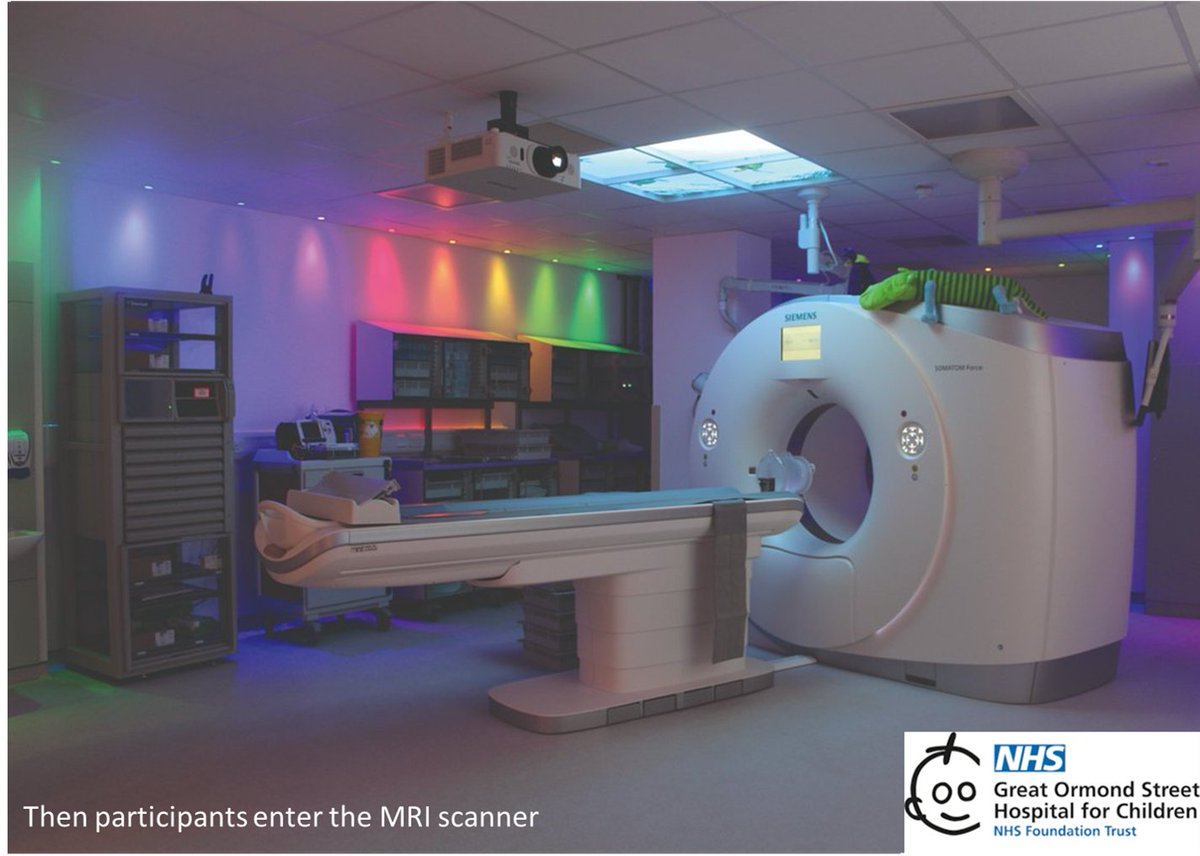

We then took our participants into the MRI scanner and showed them the words again while we recorded brain activity.

We asked participants to remember the image that was paired with the word. Unsurprisingly, the patients with developmental amnesia found this difficult, but we didn’t mind that - we were interested in the pattern of brain activity associated with the different words.

Patients with DA showed evidence that the brain *was* able to remember the associated picture. Words that had been linked with a scene picture had significantly more activity in the scene-sensitive areas of the brain than words that were linked with the scrambled scenes.

We had another memory test. This time, we asked the participants to remember if the word had been presented on the left, right or centre of the screen. In this condition, there would be no need for participants to think about the picture because it's irrelevant to the test.

In this task, the data showed that patients and controls *did not* show activity in the scene-related brain regions during this memory test.

This is known as “Retrieval Gating”. We focus our memory processing on the most relevant aspects of the memory and ignore or suppress processing of the irrelevant details.

We have previously demonstrated Retrieval Gating in healthy young adults, however, older adults seem to struggle with retrieval gating. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26351995/ ; https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0197458021000518

Our interpretation is that patients with DA can bind together associations between words and pictures at a neural level, even though they can’t remember the associations themselves when asked.

Perhaps this is one mechanism by which patients with developmental amnesia learn information about the world, even though they cannot remember their previous experiences.

We also interpret that patients with DA can engage in strategic retrieval processes that are associated with a healthy memory system, despite their lifelong memory impairment.

This research would not have been possible without the support of many colleagues at the UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health and the support of our volunteers, the patients, and their families. The project was funded by the Medical Research Council.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter