I. Among several points of interest in this recent piece is a particular story about the origins of 'Classics' and of our ideas about 'Western Civilization,' 'the Western tradition,' and so on. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/02/magazine/classics-greece-rome-whiteness.html

II. The idea ably summarized here is that 'Classics as we know it today is a creation of the 18th and 19th centuries.' Further, 'How these two old civilizations became central to American intellectual life is a story that begins not in antiquity, and not even in the Renaissance,

III. but in the Enlightenment.' In this period, 'a sort of mania' took hold of the intellectual classes, and their ideas about Greece and Rome 'cannot be separated from the discourses of nationalism, colorism and progress that were taking shape during the modern colonial period.'

IV. While it's true that 'Classics as we know it today' as a university subject has its origins in 18th and 19th centuries, I wonder whether there's a danger of defining our terms too narrowly, in a way that's paralleled in the discussion of the term 'Western Civilization.'

V. It seems true, as Gilbert Allardyce argued, that the exact term 'Western Civilization' only became common in US curricula after World War 1. https://academic.oup.com/ahr/article-abstract/87/3/695/93349

VI. But that doesn't mean the entire notion of a Western tradition was made up then; as I think Stanley Kurtz has shown, there are plenty of examples of the Western tradition being discussed before that. https://www.nas.org/reports/the-lost-history-of-western-civilization/full-report#_ftn13

VII. Unless we look only very narrowly at 'Classics as we know it today,' or at the exact phrase 'Western Civilization,' in fact, the idea that European cultures took something from the Greek and Romans seems to go back even beyond the Enlightenment.

VIII. Because the Enlightenment 'mania' for things Greco-Roman wasn't the first such mania. The Renaissance can be seen as a similar, and probably even bigger, craze for Greek and Roman culture.

IX. Nor is medieval European culture completely without a tendency to look back to the Greeks and Romans, and to re-tweet some of their memes - what language does Aquinas write in, and who does he refer to as 'the philosopher'?

X. That bring us to Christianity, a religion which emerged out of an intersection of Jewish and Greek cultures, and which made it big in the West thanks partly to the Roman Empire. It also had some impact on medieval Europe.

XI. That Greek and Roman influence was so pervasive in subsequent European culture is, actually, hardly surprising, since many later European cultures were built, to a large extent, on the ruins of Greco-Roman civilization

XII. In this perspective, classical scholarship - in the broad sense of the study of ancient Greek and Roman culture - emerges as an almost natural activity that many intellectual Europeans engaged in almost as a matter of course,

XIII. just as Chinese intellectuals looked back to their classics. For some scholars classical scholarship began in antiquity itself, in Hellenistic Alexandria in particular. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/classical-review/article/abs/philologiae-perennis-initia-pfeiffer-r-history-of-classical-scholarship-from-the-beginnings-to-the-end-of-the-hellenistic-age-pp-xviii311-oxford-clarendon-press-1968-cloth-63s-net/9D1B3A967AD0CBBF04B5FD3B53D6250A

XIV. I know that Poser's account in the piece at the top of this thread is trying to tell a story about how the way we view the ancient past has changed over time.She thinks Renaissance humanists took a more catholic, less exclusionary approach than their Enlightenment successors

XV. It's also possible to tell a story about how medievals didn't really know or care much about classical Greece; & about how New Eastern influences (esp. Hebrew) were dropped from curricula as 'liberal arts' re-defined 'Classics' as Greco-Roman in more recent times.

XVI. In the grand scheme of things, though, I would see these as differences in emphasis more than anything else; even Greekless medievals were influenced by Plato & Aristotle, and classicists have been moving East in their interests since at least the time of Zaehner.

XVII. If this way of looking at things is right, what follows? Not, of course, that anyone in the West has to do things in a 'Western way' now or in the future - Kwame Anthony Appiah is right that it would be foolish to have cultural history limit our choices in the present.

XVIII. (The world is a much more interconnected place these days, in any case, and what we may be seeing now in many countries is the emergence of a kind of post-regional, universal culture.) https://slatestarcodex.com/2016/07/25/how-the-west-was-won/

XIX. I think it does follow, though, that an interconnected but recognizably distinct Western civilization is a feature of global cultural history;

XX. just because certain people and movements have over-emphasized it, or used it to malign ends, doesn't mean it was never a thing. https://tinyurl.com/7qksfbpx

XXI. I actually happen to think it's an interesting and important thing to learn about, just as the Chinese, Islamic, and Indian intellectual traditions are for example (I say this as a someone who practises an Eastern religion)

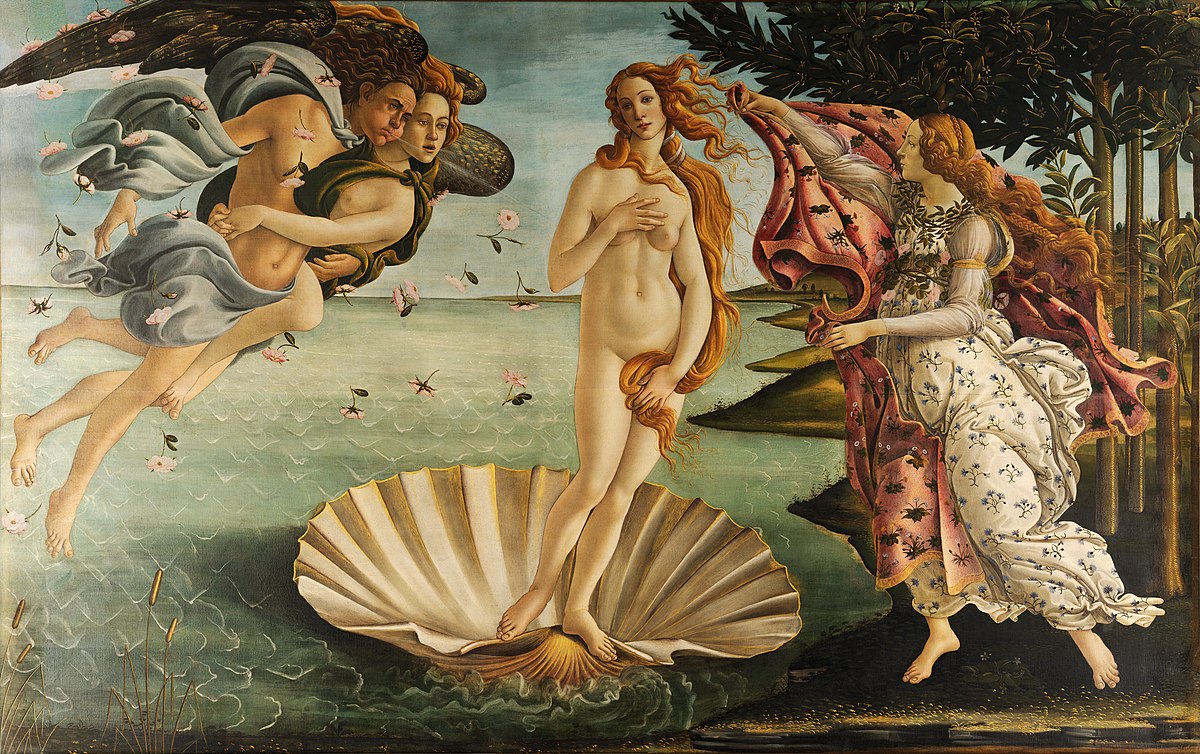

XXII. So I have to say I really don't see the problem with looking at Greece and Rome as foundational to subsequent Western thought & art. https://www.chronicle.com/article/if-classics-doesnt-change-let-it-burn

XXIII. If students want to understand any subsequent period of European culture - I understand they might not and don't have to, but if they do - it can help to understand these bewildering Greek and Roman memes that everyone keeps retweeting through European history.

XXIV. There are of course other reasons why you might want to study ancient Greek or Roman culture - for its own sake, say, or just as one ancient culture among others - but I don't think doing it as something that helps you understand later W culture is a bad one.

XXV. That's (finally) 1 of the reasons I'm glad there are departments specializing in these cultures. It's not the be-all and end-all, but I like to think that giving the key to understanding later Euro culture to anyone who wants it is among the small contributions we can make

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter