Compelling opening presentations by House impeachment managers followed by inept responses from Trump defense lawyers moved Louisiana Sen Bill Cassidy to join five Republican colleagues in voting that the trial is constitutional. What might his shift portend?

Despite emotionally moving day-2 presentations from House managers that strongly buttressed the case for conviction, political realists remain skeptical. Republican legislators, after all, have good reasons for their fear of offending the Trump base.

But pundits also overestimate the stability of the status quo. As @TimurKuran described in a 1997 book, virtually no experts foresaw the rapid breakup of the Soviet Union that began in the late 1980s (apart from a few who had predicted its collapse every year for many years).

In Kuran’s account, pundits overestimated the Soviet bloc’s stability largely because most people who lived in member countries voiced consistent support for their leaders in public opinion polls.

But because speaking out against a regime entails obvious risks, polling data were not a reliable measure. Like a Republican Senator fearful of being primaried by a Trump-inspired opponent, those who support a regime when a pollster asks may merely be trying to avoid those risks.

But there’s safety in numbers. The cost of speaking out depends in part on how many others are also speaking out. Some speak out no matter what, but others are willing to do so only if sufficiently many others join them.

The upshot is that even seemingly minor provocations or small changes in the odds of punishment can unleash a prairie fire of unexpected public opposition—first, by inducing a few additional people to speak out, which then induces still others to do so, and so on.

Dynamic processes like these often culminate in near complete reversals of public opinion. They explain why big changes sometimes happen so quickly and with so little forewarning.

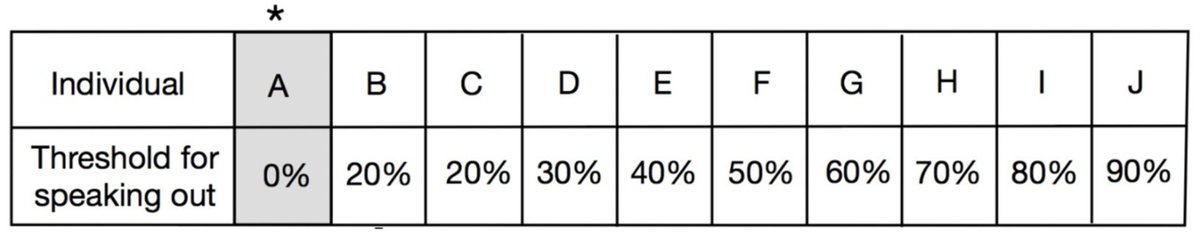

An example: imagine a population consisting of 10 citizens—call them A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, and J—who live under an authoritarian regime that they would oppose publicly if they thought it safe to do so.

Each has a threshold indicating his or her willingness to speak out as a function of how many others are speaking out. A, for example, is a radical who’s willing to speak out no matter what.

B and C are only slightly more cautious, each willing to speak out if at least 20 percent of their fellow citizens are also speaking out.

The remaining citizens have higher thresholds, as summarized in the table below. Citizen A, by assumption, will speak out irrespective of what others do. But A constitutes only 10 percent of the population, and that’s below the threshold of each of the others.

All but A will therefore remain silent. The stable outcome in this situation, indicated by the asterisk above the shaded entries in the table, is that only one in 10 citizens speak out. The regime survives. But now suppose something causes B to become less cautious.

Perhaps he is emboldened by news accounts describing how German dissidents suffered no consequences when they dismantled the Berlin Wall. Or perhaps he or a family member has suffered in some unexpected way from an action by the regime.

Whatever the cause, B’s threshold for speaking out falls from 20% to only 10%, as indicated below. Since A is already speaking out, B’s slightly lower new threshold is now met, so he too speaks out, in the process raising the percentage of citizens speaking out to 20.

This makes C willing to speak out as well, pushing the percentage to 30. E then starts speaking out, raising the percentage speaking out to 40, and so on.

In short order, a small change affecting only B causes the percentage of the population speaking out against the regime to rise from only 10 percent to 100 percent, again as indicated by the asterisk above the shaded entries in the table. This time, the regime topples.

Does this stick-figure example tell us anything about the likely outcome of Trump’s current Senate trial? Not necessarily, because we know Mitt Romney’s willingness to convict duringTrump’s first impeachment trial failed to inspire any of his Republican colleagues to join him.

Pundits are thus reasonable to be skeptical that Republican Senators will be any more courageous this time. Still, it would be a mistake to assume that they won’t be affected by the strength of the evidence and arguments presented by House impeachment managers.

The list of Senate Republicans with no reason to fear a Trump-inspired primary opponent is much longer than the four who have already announced their retirements. And in any event, that fear would not be the only element in a Senator’s cost-benefit calculus.

There is also the matter of one’s place in history. It recently seemed that events of Jan 6 might quickly fade in memory. But it's now clear that Senators' votes in this trial will be central pillars in their historical legacies. Acquittal votes will not be badges of honor.

The threat of electoral defeat is also greatly overrated. Most Senators are wealthy and would enjoy post-Senate lives of comfort and privilege. Serving in the minority has been frustrating for many, and even in the majority, Rs enacted virtually no legislation of consequence.

That said, the odds clearly still favor Trump’s acquittal. Yet most pundits continue to underestimate the threat to that prediction posed by behavioral contagion. If one more Senator experiences a change of heart like Cassidy’s, that could tip another colleague’s vote, and so on.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter