My sense is its sheer scale and unanimity would be hard to imagine, much less reproduce, now. It was enabled by the fact that Twitter was still in the process of gaining collective sentience at the time; the ideological battle lines around "cancel culture" had not yet been drawn.

If you search the relevant hashtag, you find people reposting it wistfully in recent times, longing for the era of innocent excitement it represents. It was a time when true Durkheimian collective effervescence could take hold, less tainted by bad conscience than is the case now.

On the early '10s internet, something remarkable happened: people spontaneously rediscovered the sort of unanimous collective violence that modern social structures had long strived to suppress. This discovery was in a sense truly innocent: "they knew not what they did."

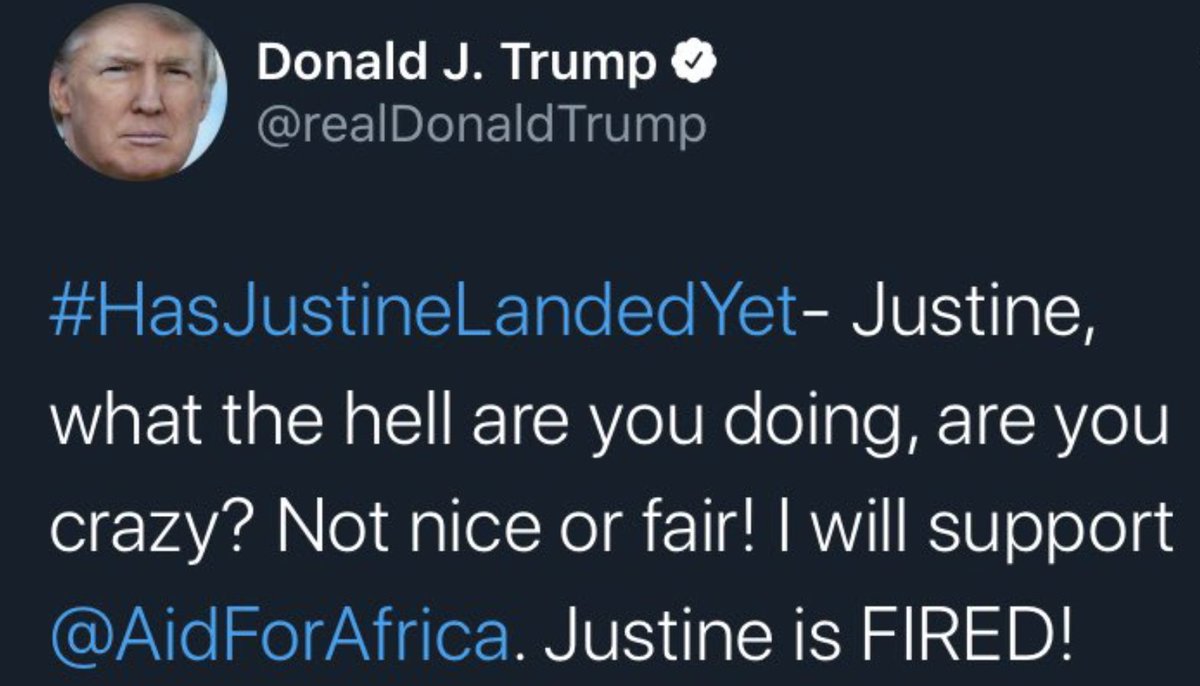

But once this pattern was recognized, two things happened: 1) it generated a reaction that drew on a general moral opprobrium against collective violence; 2) it could be strategically weaponized to achieve political ends.

In fact, these two responses were often the same response: the condemnation of scapegoating could be the basis of scapegoating, since as Girard notes: "scapegoating can continue only if its victims are perceived primarily as scapegoaters." (But this was already true of Sacco.)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter