Have you heard about the time

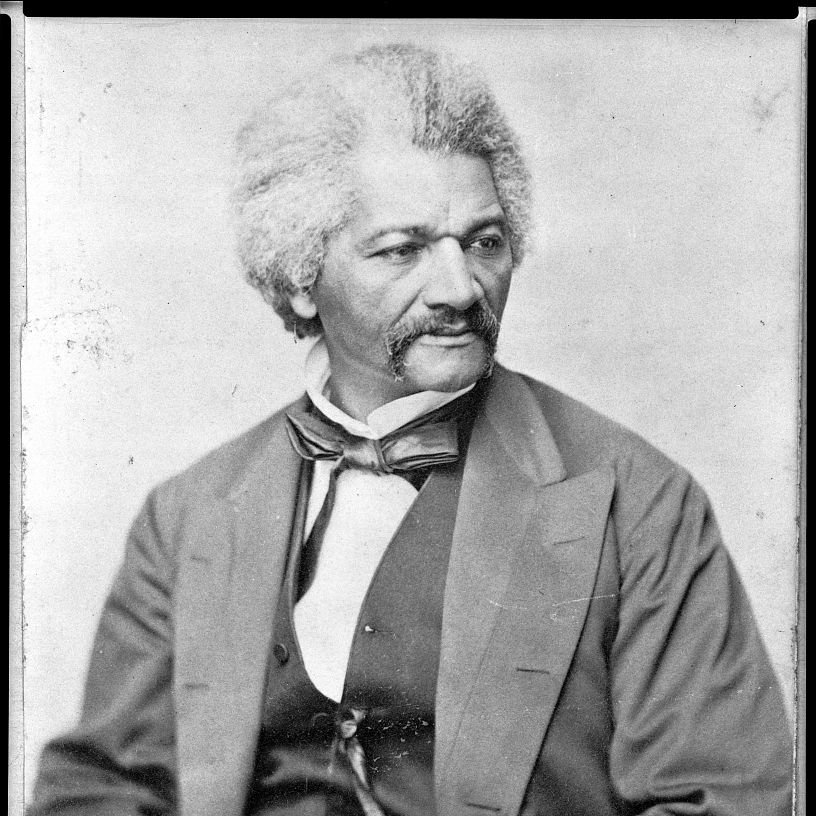

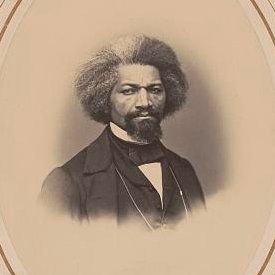

Frederick Douglass

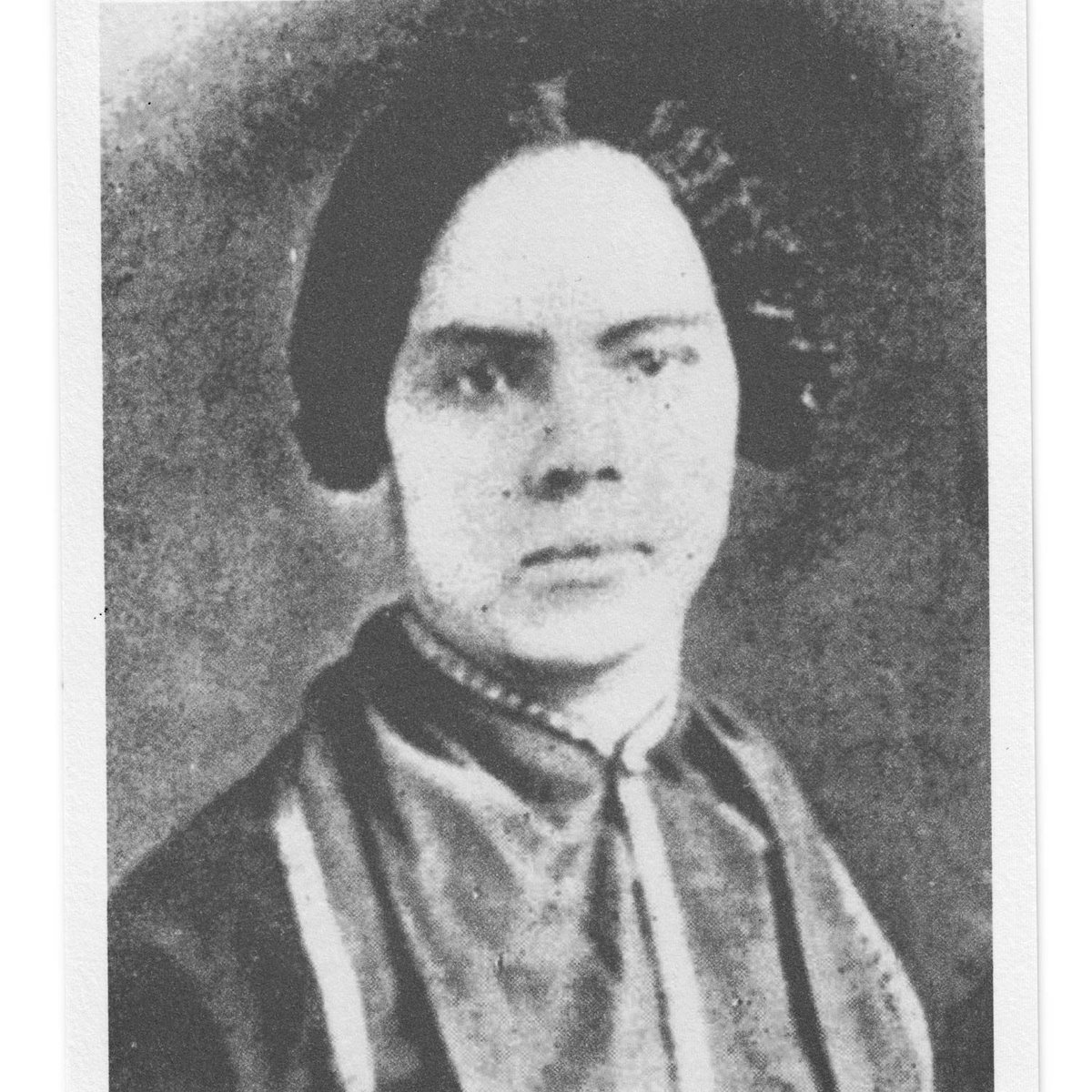

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker

Mary Ann Shadd Cary

Belva Lockwood

occupied the Washington, D.C. Board of Elections?

#DCStatehood thread

Frederick Douglass

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker

Mary Ann Shadd Cary

Belva Lockwood

occupied the Washington, D.C. Board of Elections?

#DCStatehood thread

It’s April 14, 1871.

DC’s first city-wide election is less than a week away. For the first time, the consolidated city would get to choose its own legislature and someone to represent them in Congress.

Headlines blared: “Our New Government”

DC’s first city-wide election is less than a week away. For the first time, the consolidated city would get to choose its own legislature and someone to represent them in Congress.

Headlines blared: “Our New Government”

The 15th Amendment was barely a year old.

Leading up to the April election, the local paper anxiously tallied registered voters by race, reassuring readers that the white advantage was still strong.

Leading up to the April election, the local paper anxiously tallied registered voters by race, reassuring readers that the white advantage was still strong.

Republicans were the favorites, but Washington was a southern city.

Democrats were running on the platform “Opposed to Mixed Schools.” (It was printed on the ballot.)

Women wanted in.

Democrats were running on the platform “Opposed to Mixed Schools.” (It was printed on the ballot.)

Women wanted in.

That January, Victoria Woodhull had challenged suffragists to try and register and vote, then sue and go to prison if needed to exercise their full citizenship under the 14th Amendment.

She called this strategy “the New Departure.”

She called this strategy “the New Departure.”

Local women formed the DC Women’s Franchise Association and met for months- 19 meetings! -to concoct a plan.

They took action on that Friday in April, one of the last days to register.

At 2:15, “the advance guard” arrived at City Hall: Walker, Lockwood, Douglass, a few others.

They took action on that Friday in April, one of the last days to register.

At 2:15, “the advance guard” arrived at City Hall: Walker, Lockwood, Douglass, a few others.

Stop to picture the scene. It is shortly after the Civil War. Frederick Douglass was one of the most famous men in America, and a huge presence in DC.

Dr Walker was also a public figure: well-known as a Civil War hero and a gender-bending rebel. She was unmistakable.

Dr Walker was also a public figure: well-known as a Civil War hero and a gender-bending rebel. She was unmistakable.

Belva Lockwood was not yet famous for demanding to practice law, lobbying Congress for the right to do so, arguing cases before the Supreme Court, and running for President.

In 1871 Lockwood was a suffrage leader, a 40-year-old w/a toddler, and a law student. Her husband Ezekiel came with her to register.

By 4 o’clock dozens of women had gathered at City Hall.

By 4 o’clock dozens of women had gathered at City Hall.

Sara Andrews Spencer, whose name would ultimately grace the lawsuit they intended to bring, was the ringleader. (R , about 20 years later.)

, about 20 years later.)

Editor and lawyer Mary Ann Shadd Cary was there—white women may not have recognized her, but Frederick Douglass respected her enormously.

, about 20 years later.)

, about 20 years later.)Editor and lawyer Mary Ann Shadd Cary was there—white women may not have recognized her, but Frederick Douglass respected her enormously.

The large group was greeted by the man in charge, John S. Crocker. He was African American, one of two Black men on the 7-member Board of Registration.

“The board is obliged to deprive itself of the agreeable duty of complying with your request,” he said.

“The board is obliged to deprive itself of the agreeable duty of complying with your request,” he said.

Between the would-be voters and the husbands and lawyers accompanying them, there were at least 100 people crowded around inside City Hall.

Crocker apologetically tried to encourage them to give up and go home.

Crocker apologetically tried to encourage them to give up and go home.

Not a chance. The women insisted on being treated like ordinary registrants.

After some fussing, each woman was allowed to register at the proper desk for her district. She swore out an affidavit with her name, her residence, and that she wished to register.

After some fussing, each woman was allowed to register at the proper desk for her district. She swore out an affidavit with her name, her residence, and that she wished to register.

Dr. Walker couldn’t resist a speech:

“Gentlemen...So long as you tax women, and deprive them of the franchise, you but make yourselves tyrants. You imprison women for crimes you have forbidden women to legislate upon.

“Gentlemen...So long as you tax women, and deprive them of the franchise, you but make yourselves tyrants. You imprison women for crimes you have forbidden women to legislate upon.

“Either do not hold women responsible for any crimes, do not tax their property...or give woman her rights as a human being.”

At least 68 women tried to register that day.

At least 68 women tried to register that day.

The group had prepared a petition in advance. Lockwood is on that list, but Shadd Cary and Dr Walker aren’t. Shadd Cary may have decided to join at the last minute. Perhaps Walker wanted to register in NY, where she later ran for office.

Shadd Cary may have decided to join at the last minute. Perhaps Walker wanted to register in NY, where she later ran for office.

Shadd Cary may have decided to join at the last minute. Perhaps Walker wanted to register in NY, where she later ran for office.

Shadd Cary may have decided to join at the last minute. Perhaps Walker wanted to register in NY, where she later ran for office.

But they were definitely there.

Shadd Cary wrote an essay about the day, called “A First Vote, Almost.”

At least two other Black women sought to register: Amanda Wall and Mary Anderson. As was common then, they are listed on the petition with “col’d” after their names.

Shadd Cary wrote an essay about the day, called “A First Vote, Almost.”

At least two other Black women sought to register: Amanda Wall and Mary Anderson. As was common then, they are listed on the petition with “col’d” after their names.

A white woman who tried to register that day was fired from her job. A federal civil servant was threatened with dismissal.

Some newspaper wags suggested the women’s husbands would divorce them, but there are no reports of splits.

Some newspaper wags suggested the women’s husbands would divorce them, but there are no reports of splits.

Five days later the group met at Sara Spencer’s Spencerian Business College to discuss what to do the next morning, Election Day.

Their denied registrations were enough to sue the Board of Registration, but to sue the Board of Elections they needed to try and actually vote.

Their denied registrations were enough to sue the Board of Registration, but to sue the Board of Elections they needed to try and actually vote.

Elsewhere in the city, the Board of Elections was having its own meeting that night. “They knew that they would be sued if they rejected their ballots, and they felt that the City Government would sue them if they accepted them.”

On the morning of April 20, 1871,

On the morning of April 20, 1871,

women went to the polls all over the city.

Each woman insisted the pollworker search the rolls for her name. Not being found, she handed over a prepared affidavit:

I am a resident of DC;

a legally qualified voter under the Constitution;

I sought to register and was refused.

Each woman insisted the pollworker search the rolls for her name. Not being found, she handed over a prepared affidavit:

I am a resident of DC;

a legally qualified voter under the Constitution;

I sought to register and was refused.

Spoilers: they lost their lawsuit. And DC’s partial self-rule lasted three years.

As it happens, one of the only places women COULD vote then was Wyoming—a smaller population than DC, then and now.

150 years later, Wyoming has 2 Senators; DC 0.

#19thamendment #DCStatehoodNow

As it happens, one of the only places women COULD vote then was Wyoming—a smaller population than DC, then and now.

150 years later, Wyoming has 2 Senators; DC 0.

#19thamendment #DCStatehoodNow

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter