Well it's #NationalPoopDay so here is a thread about our latest Paisley Caves  paper! You can find our paper here (open access

paper! You can find our paper here (open access  ) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12520-020-01160-9 Team members on twitter: @ArchaeologyLisa @dribull @istolethursday @KateMcD_Archy 1/

) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12520-020-01160-9 Team members on twitter: @ArchaeologyLisa @dribull @istolethursday @KateMcD_Archy 1/

paper! You can find our paper here (open access

paper! You can find our paper here (open access  ) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12520-020-01160-9 Team members on twitter: @ArchaeologyLisa @dribull @istolethursday @KateMcD_Archy 1/

) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12520-020-01160-9 Team members on twitter: @ArchaeologyLisa @dribull @istolethursday @KateMcD_Archy 1/

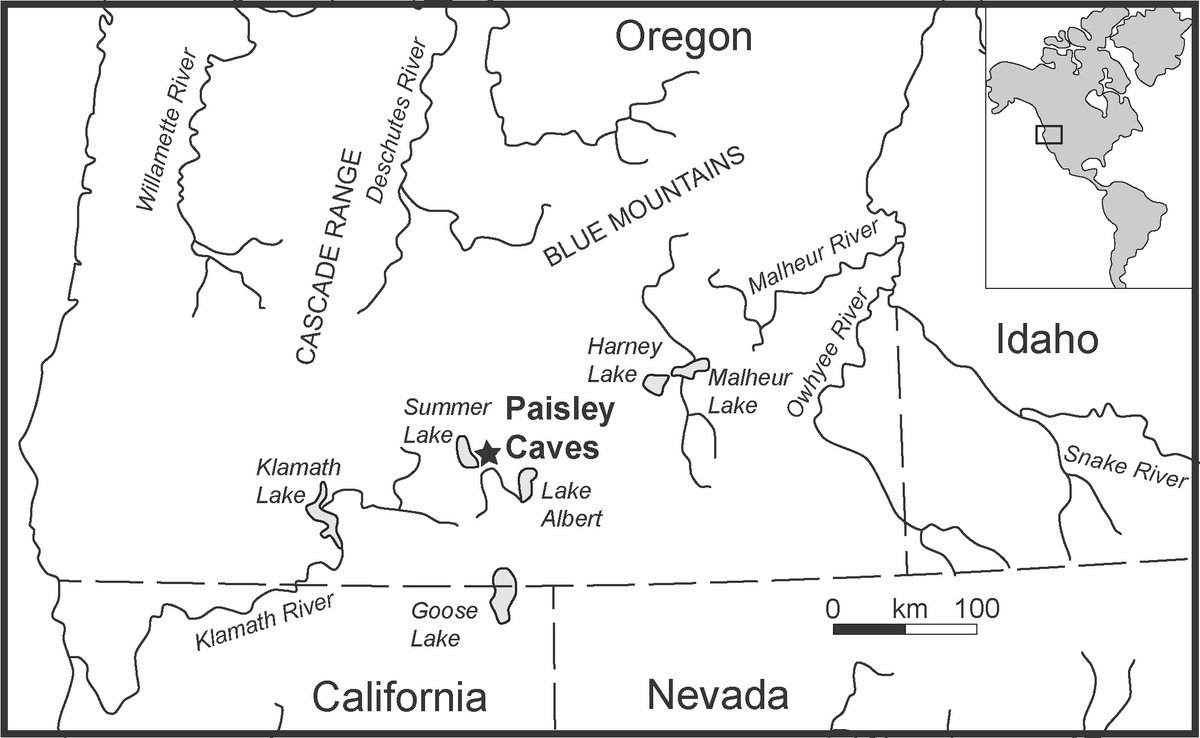

We set out to test ideas about hunter-gatherer diets in the Great Basin during the Younger Dryas (12,900 to 11,700 years ago) and early Holocene (11,700 to 8,900 years ago). These sites fall in the Western Stemmed Tradition (WST) 'cause they have large stemmed stone points 2/

Many WST sites are found near what used to be wetlands (dried up in the Holocene). We find the remains of small animals, insects, fish, shellfish, and various types of plants preserved at archaeological sites in dry caves; much of this appears to be linked to food practices 3/

But, but we don't see groundstone tools indicating intensive seed processing like we do in the later Holocene. And it can sometimes be hard to tell if things like insect remains, small mammal bones, and seeds are from people food, or from other critters living in the caves 4/

Some archaeologists think that stemmed points must have been used to hunt large mammals like pronghorn antelope and possibly the last vestiges of the now-extinct Pleistocene elephants, camels, and horses 5/

Geochemical analysis tells us that the rock used to make stemmed points came from geologic sources a hundred miles away or more! This suggests people were covering long distances throughout the year, and is more common in folks with a focus on large-mammal hunting 6/

So, were people focused on hunting large mammals, or did they eat a variety of plant and animal foods? Or somewhere in between, changing focus depending on the season or availability of resources? A big issue in answering this is the lack of direct evidence for WST diet 7/

That's where  research comes in! Our team did a comprehensive analysis of nine Paisley Caves

research comes in! Our team did a comprehensive analysis of nine Paisley Caves  spanning the Younger Dryas and early Holocene. This was a team effort bringing together people with expertise in biomolecular, plant, insect, and vertebrate analysis 8/

spanning the Younger Dryas and early Holocene. This was a team effort bringing together people with expertise in biomolecular, plant, insect, and vertebrate analysis 8/

research comes in! Our team did a comprehensive analysis of nine Paisley Caves

research comes in! Our team did a comprehensive analysis of nine Paisley Caves  spanning the Younger Dryas and early Holocene. This was a team effort bringing together people with expertise in biomolecular, plant, insect, and vertebrate analysis 8/

spanning the Younger Dryas and early Holocene. This was a team effort bringing together people with expertise in biomolecular, plant, insect, and vertebrate analysis 8/

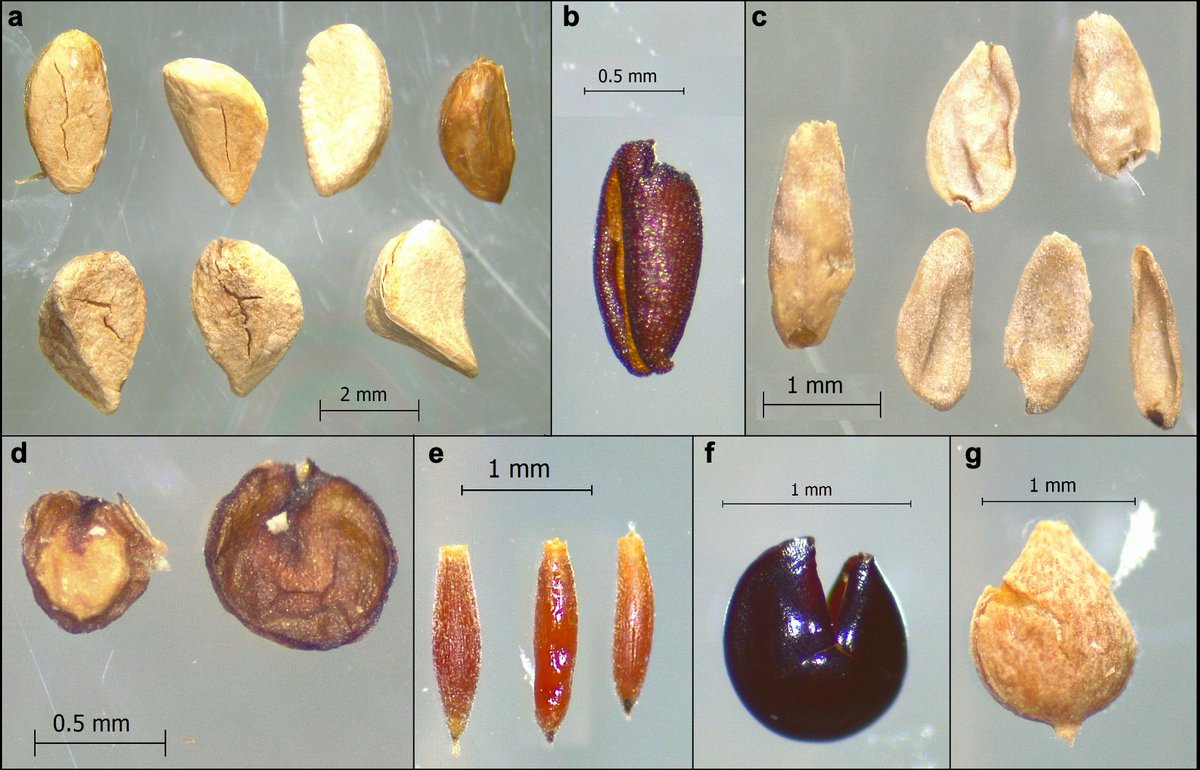

Seeds in the  give us good evidence that people were eating rose hips, mustards, grasses, cattail, pigweed, and sedge

give us good evidence that people were eating rose hips, mustards, grasses, cattail, pigweed, and sedge

9/

9/

give us good evidence that people were eating rose hips, mustards, grasses, cattail, pigweed, and sedge

give us good evidence that people were eating rose hips, mustards, grasses, cattail, pigweed, and sedge

9/

9/

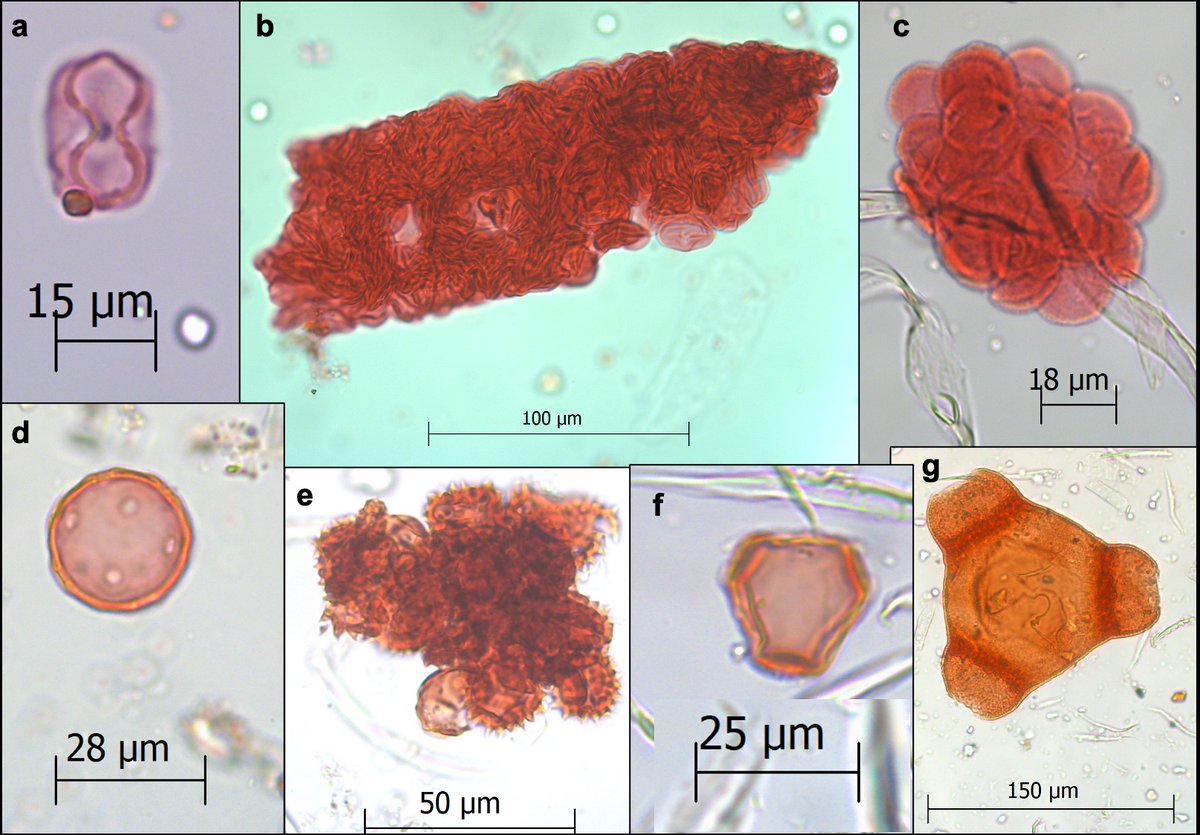

Pollen in the  gives us microscopic clues that people ate legume flowers and plants in the grass, pigweed/goosefoot, sedge, cattail, buckthorn, and evening primrose families

gives us microscopic clues that people ate legume flowers and plants in the grass, pigweed/goosefoot, sedge, cattail, buckthorn, and evening primrose families

10/

10/

gives us microscopic clues that people ate legume flowers and plants in the grass, pigweed/goosefoot, sedge, cattail, buckthorn, and evening primrose families

gives us microscopic clues that people ate legume flowers and plants in the grass, pigweed/goosefoot, sedge, cattail, buckthorn, and evening primrose families

10/

10/

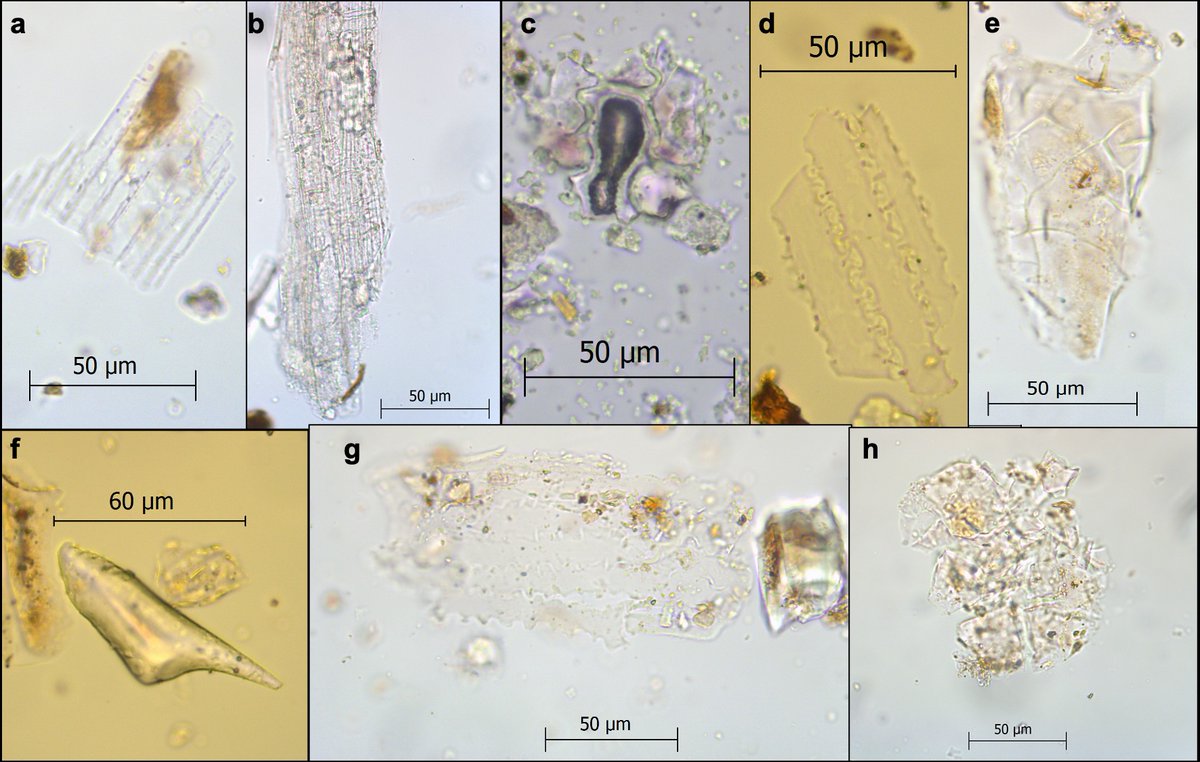

Phytoliths—silica structures that form in some plant cells—give use more microscopic clues of plant food in the diet, although the phytoliths we found only really tell us that people ate plenty of leafy material from monocot and dicot plants 11/

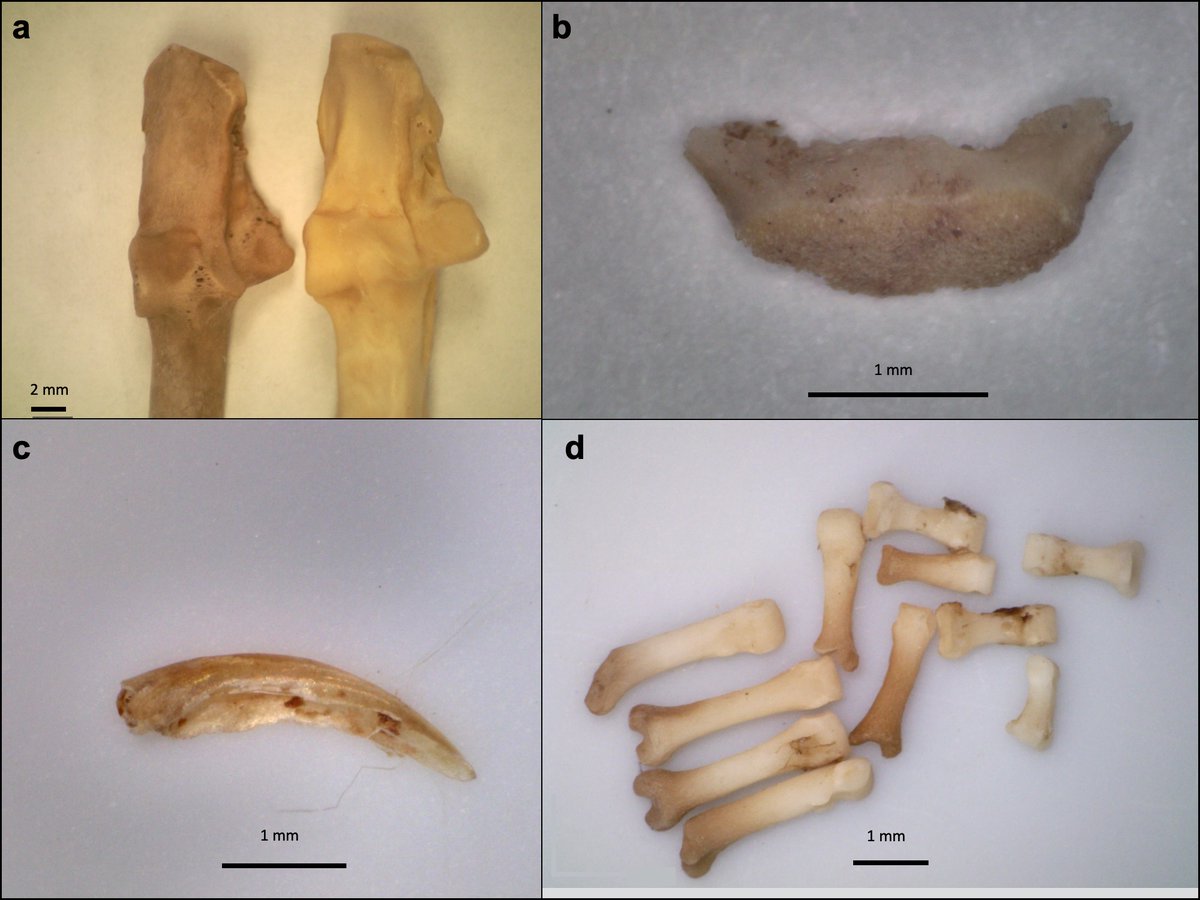

Animal bones in human  are usually pretty broken up by the time they come out and are difficult to identify. Despite this, we identified bones from hare/jackrabbit, bird, fish, and rodent. We found rodent toe bones and toenails indicating someone snacked on whole rodent

are usually pretty broken up by the time they come out and are difficult to identify. Despite this, we identified bones from hare/jackrabbit, bird, fish, and rodent. We found rodent toe bones and toenails indicating someone snacked on whole rodent  12/

12/

are usually pretty broken up by the time they come out and are difficult to identify. Despite this, we identified bones from hare/jackrabbit, bird, fish, and rodent. We found rodent toe bones and toenails indicating someone snacked on whole rodent

are usually pretty broken up by the time they come out and are difficult to identify. Despite this, we identified bones from hare/jackrabbit, bird, fish, and rodent. We found rodent toe bones and toenails indicating someone snacked on whole rodent  12/

12/

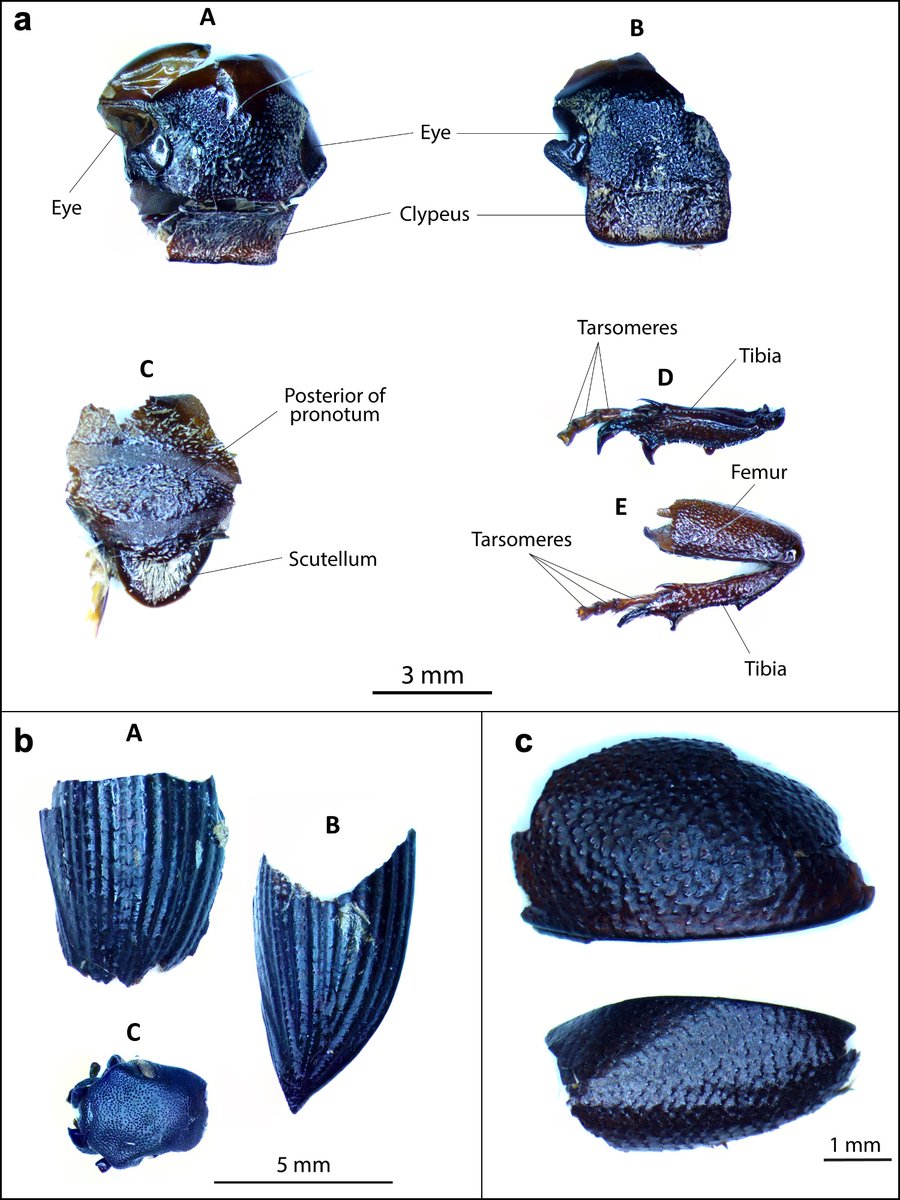

One coprolite dating to the early Holocene was full of insect remains indicating that ten-lined June beetle, Jerusalem cricket, and desert stink beetles were on the menu  13/

13/

13/

13/

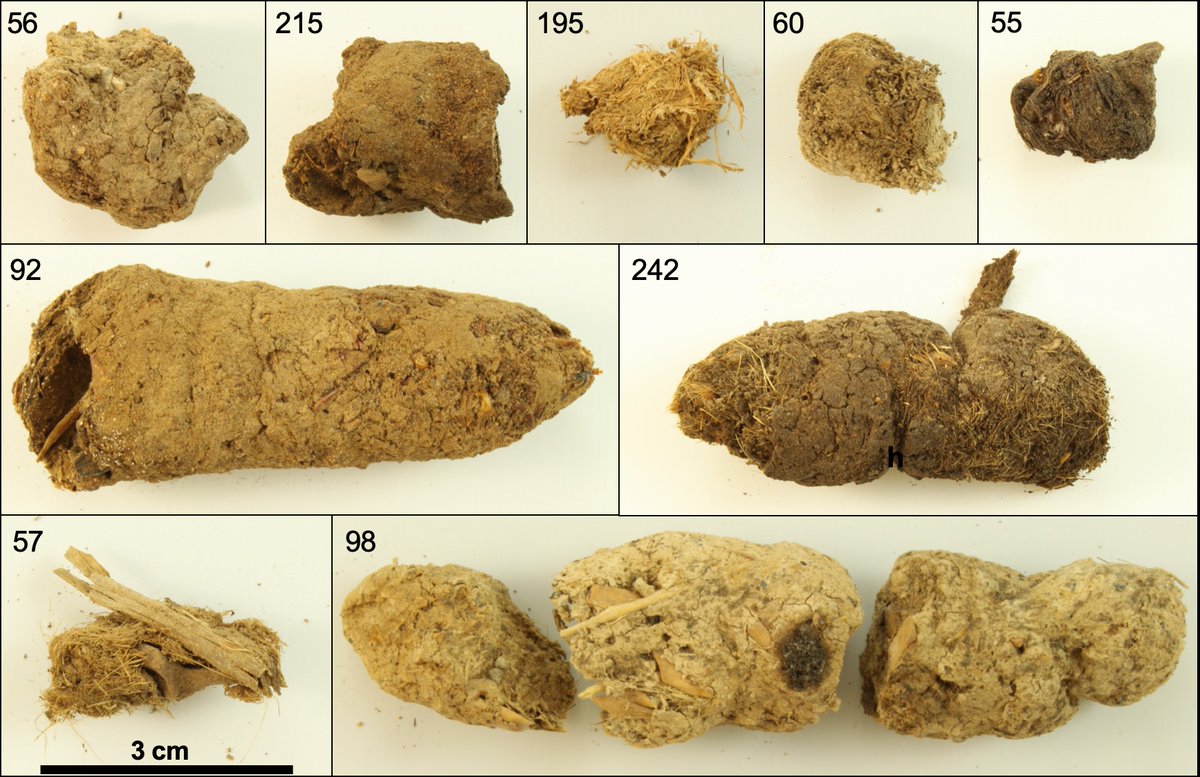

We know the  are human, because we analyzed fecal biomarkers in the

are human, because we analyzed fecal biomarkers in the  and they came from a human digestive system! There is one exception:

and they came from a human digestive system! There is one exception:  195 in the photo above had remnants of a human diet, but had fecal biomarkers from both human and carnivore digestive systems

195 in the photo above had remnants of a human diet, but had fecal biomarkers from both human and carnivore digestive systems

14/

14/

are human, because we analyzed fecal biomarkers in the

are human, because we analyzed fecal biomarkers in the  and they came from a human digestive system! There is one exception:

and they came from a human digestive system! There is one exception:  195 in the photo above had remnants of a human diet, but had fecal biomarkers from both human and carnivore digestive systems

195 in the photo above had remnants of a human diet, but had fecal biomarkers from both human and carnivore digestive systems

14/

14/

Could this be someone's dog "cleaning up" human feces in camp? Maybe, but we can't rule out wolves, coyotes, or a big cat stopping in after people left and having a little snack. Side note—my dog Peanut would totally eat human poop on the ground or any poop for that matter  15/

15/

15/

15/

The fecal biomarker methods are the same that we published last year https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/6/29/eaba6404 16/

So, what did we learn about WST diets at Paisley Caves? We found direct evidence that people had really broad diets during this time. No second guessing whether the rodent bones, seeds, or insect legs are linked to human diets when they are in

17/

17/

17/

17/

This matches evidence from other sites that people camping in caves ate a variety of foods, and not just large mammals. But, it's important to remember that large mammal bones aren't typically found in  (ouch!), so coprolites can be biased towards the small stuff 18/

(ouch!), so coprolites can be biased towards the small stuff 18/

(ouch!), so coprolites can be biased towards the small stuff 18/

(ouch!), so coprolites can be biased towards the small stuff 18/

We know from the archaeological deposits in the caves that people did eat things like pronghorn antelope. Still, these is a pretty clear signal for a diverse diet during the WST! 19/

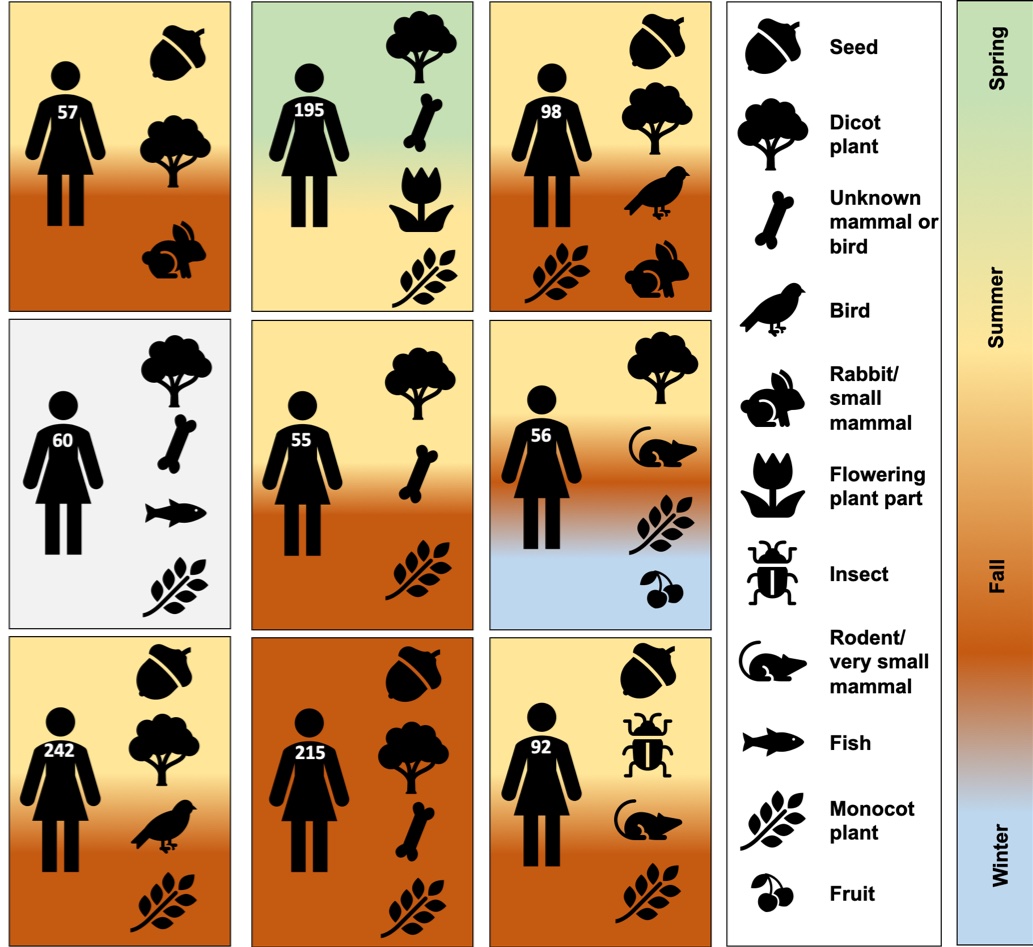

We also looked at season of occupation and where people were getting food based on the food remains in  . The figure below summarizes our results. It looks like people were camping at Paisley in the summer and fall, and were eatin' on wetland and grassland resources 20/

. The figure below summarizes our results. It looks like people were camping at Paisley in the summer and fall, and were eatin' on wetland and grassland resources 20/

. The figure below summarizes our results. It looks like people were camping at Paisley in the summer and fall, and were eatin' on wetland and grassland resources 20/

. The figure below summarizes our results. It looks like people were camping at Paisley in the summer and fall, and were eatin' on wetland and grassland resources 20/

Is this the whole picture of WST diets? We don't think so. We need better dietary data from a sites representing winter and spring camps so we can get a fuller picture of seasonal variability in diet 21/

We also have a small # of samples for a broad time period, so we surely missed diet variability at the Paisley Caves themselves. Still, even with this small # of samples we have some interesting results that contribute to our understanding of food practices in the past! 22/

So, for #NationalPoopDay I hope this thread highlights all of the amazing information stored in little nuggets of  ! We are still working on publishing our data from the Paisley Caves, and we've only just scratched the surface with this paper. Stay tuned for more

! We are still working on publishing our data from the Paisley Caves, and we've only just scratched the surface with this paper. Stay tuned for more  23/

23/

! We are still working on publishing our data from the Paisley Caves, and we've only just scratched the surface with this paper. Stay tuned for more

! We are still working on publishing our data from the Paisley Caves, and we've only just scratched the surface with this paper. Stay tuned for more  23/

23/

One last thing—I learned to love  and all that it can teach us from Dr. Vaughn Bryant. We recently lost Vaughn and I just wanted to recognize the attentive, caring, and enthusiastic teacher that he was. Vaughn won’t be forgotten by the generations of students he touched

and all that it can teach us from Dr. Vaughn Bryant. We recently lost Vaughn and I just wanted to recognize the attentive, caring, and enthusiastic teacher that he was. Vaughn won’t be forgotten by the generations of students he touched

and all that it can teach us from Dr. Vaughn Bryant. We recently lost Vaughn and I just wanted to recognize the attentive, caring, and enthusiastic teacher that he was. Vaughn won’t be forgotten by the generations of students he touched

and all that it can teach us from Dr. Vaughn Bryant. We recently lost Vaughn and I just wanted to recognize the attentive, caring, and enthusiastic teacher that he was. Vaughn won’t be forgotten by the generations of students he touched

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter