There’s a lot of interest in the Great Inflation of the 1970s these days. A thread on my new paper with I. Drechsler and P. Schnabl, which explains why inflation rose, why it fell, and why it brought high unemployment/low GDP growth ("stagflation”).

We show that the Great Inflation was due to a broken financial system that kept the Fed’s interest rate policy from reaching ordinary households. This made monetary policy ineffective in curbing inflation.

The financial system was broken because of Regulation Q. Reg Q was a law that made it illegal for banks to pay more than a fixed interest rate on deposits. For example, the ceiling rate on savings deposits was about 5%:

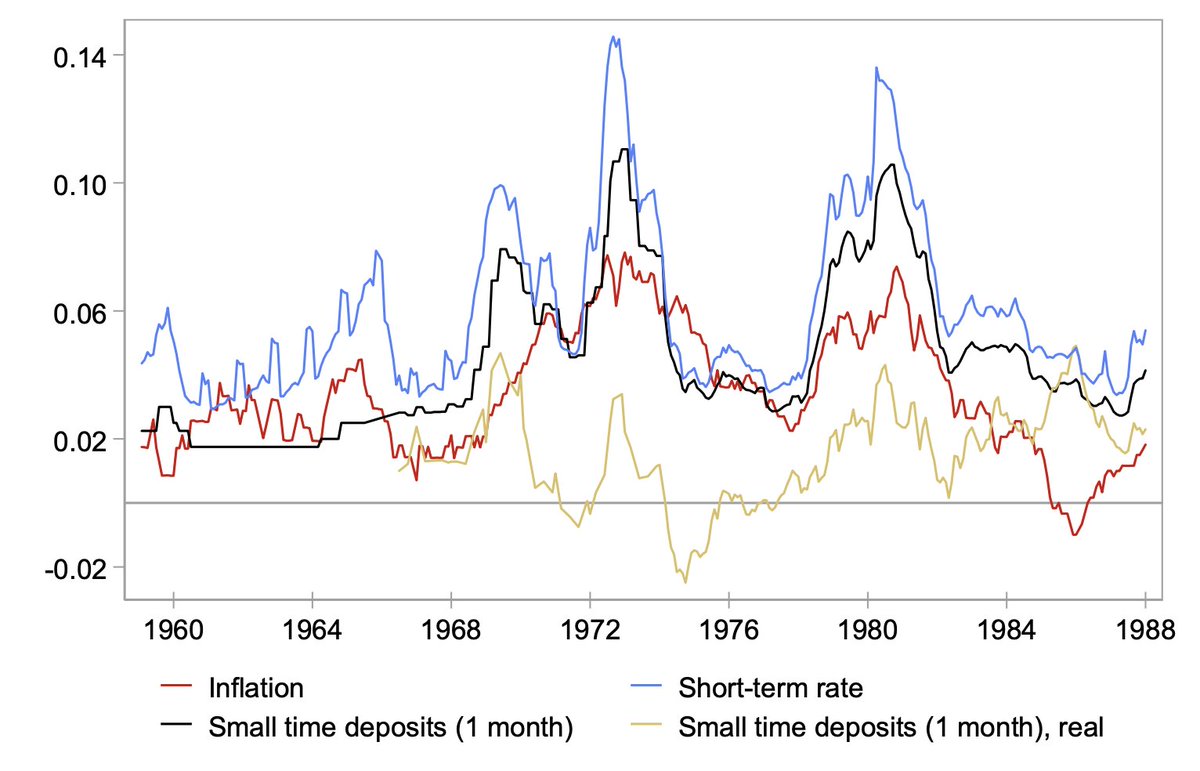

In 1965, the economy was running hot and inflation ticked up. The Fed raised rates but deposit rates hit the ceiling. People just weren't seeing the Fed’s higher interest rates in their bank accounts.

Instead, the higher inflation was eating away at their savings. So households increased spending, which led to more inflation. So they increased spending more, which led to even more inflation – an inflation spiral.

The Fed kept raising rates but because of Reg Q it didn’t matter – the transmission of monetary policy through the financial system was broken.

It got so bad that by 1979 households were getting a -7% real rate on deposits (by contrast, the real Federal funds rate was close to zero):

This massive disincentive to save explains the double-digit inflation (and the run-up in house prices). But what about the “stag” part of stagflation (high unemployment/low GDP growth)? Reg Q can explain that too.

While most households kept their savings in deposits, wealthy households had alternatives like money market funds. Whenever the Fed raised rates and Reg Q became more binding, they just took their money out.

This led to massive credit crunches as banks (and S&Ls) were forced to cut lending. The credit crunches dealt a negative supply shock to the economy at the same time as demand from households was high:

The combination of high demand and low supply pushes inflation higher while shrinking output and creating unemployment – stagflation.

So what ended the stagflation? By the late 1970s everyone was fed up with Reg Q. Congress finally repealed it in steps starting in late 1978 and 1979 by allowing banks to offer new, unregulated deposit products.

The rates on these new products (MMCs and SSCs) shot up far above the old ceilings. Households poured vast sums into them, the equivalent of 16% of GDP (~$3.5 trillion today). Within a year, deposit rates had increased by over 7% and monetary policy transmission was restored:

Inflation dropped quickly (it had already dropped in half by the time Volcker hiked rates at the end of 1980). This made the real rate on deposits go up even more. The inflation spiral was going in reverse and the credit crunches were over.

At this point you might be thinking, what about the oil shocks? The first oil shock came in October 1973 and the second in 1979 - they were important but inflation was already up a lot and persistent. This is why the standard narrative focuses on the Fed and Paul Volcker.

What about other countries that didn't have Reg Q? It turns out many had equivalent forms of financial repression, some on the deposit side, others on the asset side of bank balance sheets. Either way, financial repression blocked monetary policy transmission.

One exception was Germany, which abolished its version of Reg Q in 1965. Consistent with the importance of monetary policy transmission, Germany had high deposit passthrough and relatively mild inflation:

So what are the lessons for today? The most straight-forward lesson is that since we don’t have Reg Q on the books, runaway inflation is less likely to be right around the corner.

More broadly, the standard view of the 1970s is that the Fed didn’t fight inflation hard enough. Over time, it lost credibility and inflation expectations drifted up. It took Volcker’s sustained rate hike (and a huge recession) to restore credibility and bring inflation down.

Based on this credibility view, the Fed’s loose monetary policy over the past decade should have set off runaway inflation. This is why some observers keep predicting runaway inflation even though it keeps not happening.

Reg Q helps understand why. Unlike in the 1970s, monetary policy transmission is not broken and the Fed can do its job. Moreover, credibility is less fragile than we thought – it does not hinge on the details of the Fed’s policy rule.

If there is a transmission problem today it is a different one: the zero lower bound. Unlike Reg Q – a deposit rate ceiling – the ZLB is a deposit rate floor. And just like Reg Q led to high inflation, the ZLB is thought to contribute to low inflation today.

So the transmission view helps us make sense of both the 1970s and the 2010s (and Japan but let’s leave that for another day). It tells us to focus less on the details of the Fed’s policy rule and more on whether it reaches people through the financial system.

If you’re interested to know more about this research, check out our paper. It has a lot of evidence I didn’t get to, like the famous NOW Account experiment in New England:

http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~asavov/alexisavov/Alexi_Savov_files/DSS_Inflation_Feb_2020.pdf

http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~asavov/alexisavov/Alexi_Savov_files/DSS_Inflation_Feb_2020.pdf

We’ve also prepared slides and a non-technical summary, which you can find here:

http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~asavov/alexisavov/Alexi_Savov_files/DSS_Inflation_Slides_Feb_2020.pdf https://voxeu.org/article/what-really-drives-inflation

http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~asavov/alexisavov/Alexi_Savov_files/DSS_Inflation_Slides_Feb_2020.pdf https://voxeu.org/article/what-really-drives-inflation

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter