The #SuperBowl  has long been the top sports event in the US. But 100 years ago pro football was a minor league affair, viewed as derivative to the college game.

has long been the top sports event in the US. But 100 years ago pro football was a minor league affair, viewed as derivative to the college game.

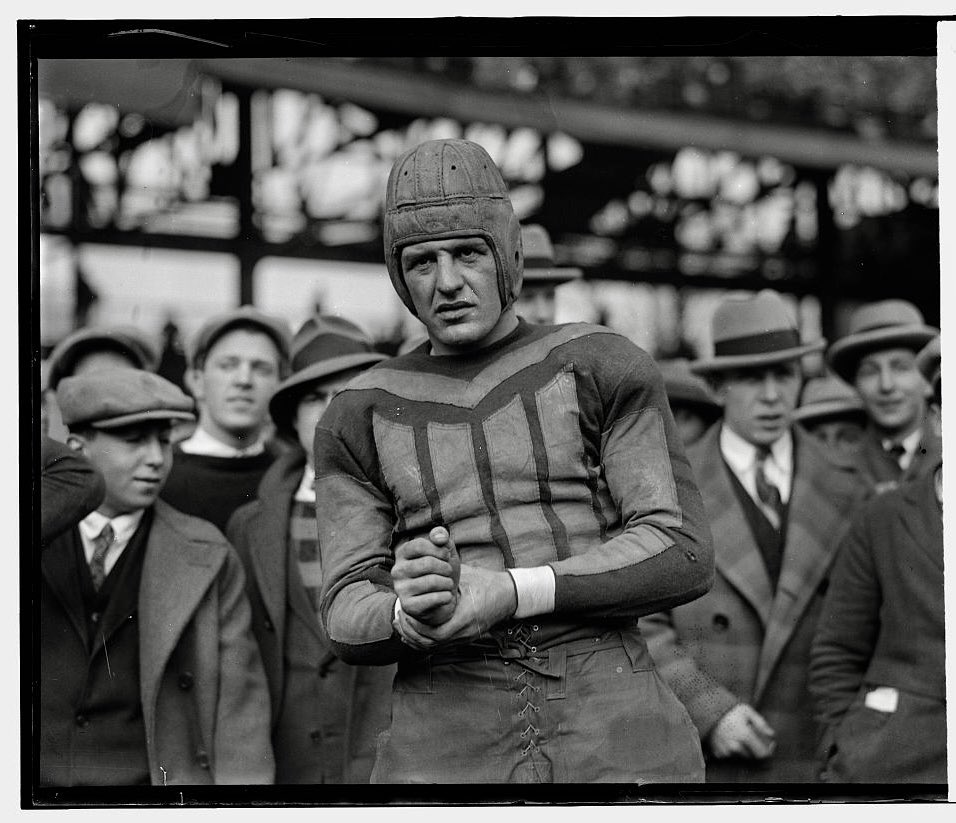

To see how far the @nfl has come, let’s look at the backlash in 1925 when college star Red Grange turned pro

has long been the top sports event in the US. But 100 years ago pro football was a minor league affair, viewed as derivative to the college game.

has long been the top sports event in the US. But 100 years ago pro football was a minor league affair, viewed as derivative to the college game.To see how far the @nfl has come, let’s look at the backlash in 1925 when college star Red Grange turned pro

Grange, star halfback for @IlliniFootball, wasn’t the first college player to go pro. But his considerable fame and the way he announced his decision—immediately after his last college game—made him a national scandal.

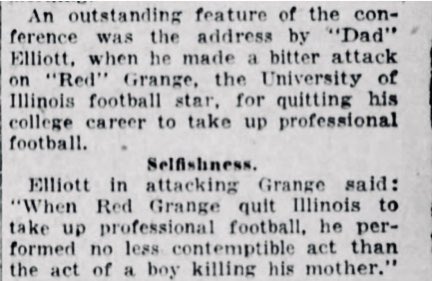

One former player said it was akin to killing one’s mother

One former player said it was akin to killing one’s mother

Grange’s college coach, Robert Zuppke, had a hard time with it too. At an end-of-the-year team banquet, he gave a passionate speech lamenting Grange’s decision.

Grange was in attendance and he left mid-speech, which the Illinois student newspaper tried to explain away

Grange was in attendance and he left mid-speech, which the Illinois student newspaper tried to explain away

Other guardians of college football weighed in. The American Football Coaches Association passed a resolution banning members from associating with pro football (left).

Big 10 commissioner John Griffith expressed sympathy, but also sorrow that Grange was being exploited (right)

Big 10 commissioner John Griffith expressed sympathy, but also sorrow that Grange was being exploited (right)

What was going on here? What was the logic behind this backlash?

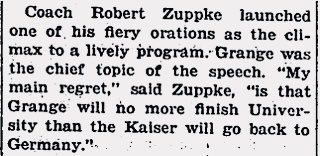

Football coach Amos Alonzo Stagg, who coached against Grange, laid out the basic reasoning in his 1927 autobiography. He noted the post-Grange rise of pro football, but saw it as a parasite on the college game.

Football coach Amos Alonzo Stagg, who coached against Grange, laid out the basic reasoning in his 1927 autobiography. He noted the post-Grange rise of pro football, but saw it as a parasite on the college game.

He went on to argue that pro football could never replicate the popularity of the college version because it could not foster the spirit of college sports, where players competed out of love for the game, each other, and their school.

It was, he said, like love of country.

It was, he said, like love of country.

He also explained that this college spirit was represented by the “Order of the C,” a club he created at Chicago to honor athletes who supposedly represented his amateur sport ideals.

Members of the club, Stagg said, were unlikely to debase themselves by pursuing “easy money”

Members of the club, Stagg said, were unlikely to debase themselves by pursuing “easy money”

And if pro football managed to defy Stagg’s predictions and overtake the college version, Stagg declared that “we shall have to plough up our football fields” because the game would no longer be a force for building character

Stagg’s view was not universal. While many within college sports expressed outrage or concern with Grange’s decision, others saw nothing wrong.

James Naismith fit this camp. Asked about Grange, he said that if coaches could get paid, there was no harm in players getting paid

James Naismith fit this camp. Asked about Grange, he said that if coaches could get paid, there was no harm in players getting paid

DeHart Hubbard supported Grange, too. A former track star at Michigan and the first Black athlete to win individual gold in the Olympics (1924), Hubbard wrote a column stating he would do the same thing if he could

Ironically, soon after that column, Hubbard was lifted up as the anti-Grange by a white Methodist magazine. Using racialized language, the Christian Advocate praised Hubbard for accepting a YMCA job rather than turning pro

But Hubbard saw things more clearly than most.

Not only did he support athletes turning pro, he also recognized that Grange’s fame was less about his on-field abilities than the power of publicity. Here he compares Grange with Fritz Pollard (one of the first Black NFL players)

Not only did he support athletes turning pro, he also recognized that Grange’s fame was less about his on-field abilities than the power of publicity. Here he compares Grange with Fritz Pollard (one of the first Black NFL players)

As it turned out, Grange was a solid pro but hardly the mythological “Galloping Ghost” of his college years.

Still, his decision did help to legitimize pro football a bit, and he also helped normalize the idea that there was nothing wrong with college players turning pro

Still, his decision did help to legitimize pro football a bit, and he also helped normalize the idea that there was nothing wrong with college players turning pro

Grange’s role in those developments should not be overstated. He served as a symbol of larger debates about the compatibility of college and pro football, debates that now seem obsolete.

The NFL rode TV to sports supremacy in the 1960s. The football fields are not plowed up yet

The NFL rode TV to sports supremacy in the 1960s. The football fields are not plowed up yet

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter