There are two lines of thought about 'concepts' in philosophy: one that sees them as shared ideals (either metaphysically (Plato/Frege) or socially (Hegel/Brandom)), and one that sees them as cognitive components (either psychologically (Kant/Fodor) or socially (Quine/Wilson)). https://twitter.com/AlldrittOwen/status/1357848457759883264

The concept [concept] is a peculiarly reflexive knot of misunderstanding not simply between philosophy and other disciplines (e.g., psychology and sociology), but internally between basically everyone in a every philosophical tradition and subfield. It's a semantic clusterfuck.

I've said a few times on here that I'm quite influenced by Wilson's analysis of these problems, both his insistence on using more complex working examples (e.g., 'toughness' rather than 'red'), and the idea that the psychological metaphor of 'concept possession' causes problems.

The German 'Begriff' implicitly included a better metaphor - 'grip', which admits of degrees beyond 'do you have it or don't you?'. It's clear that students get bootstrapped through stages of conceptual competence (e.g., 'atom'), and it's arguable that there's no terminal stage.

But it's important to see that this idea straddles the two strands, because we're talking about something like the (psychological) internalisation of a (sociological) set of practices, that aims beyond itself at some (metaphysically) external ideal or real structure.

The insights that force this view all come from the recognition that concepts change (sense), even and especially in order to remain the same (reference). We can talk about how the usage of the term 'electron' evolved from the C19th to now, by *assuming* continuity of reference.

If we do the same to the concept 'phlogiston', we can and do talk about its history without assuming that it refers to anything at all. The most difficult thing is to consistently articulate what concepts are (psycho-sociologically) when we *bracket* assumptions about reference.

This is basically what Foucault's approach to discourse does, and it's quite explicitly modelled on Husserl, even though his theory regarding how (noematic) reference works owes more to Kant and his sociologically oriented successors (e.g., French philosophy of science).

But there are various frameworks people have developed to do it. Brandom's approach is excellent, as long as you avoid the formal semantics that has increasingly pushed him back towards Aristotelianism (via Lewis). Again, Wilson's framework and its test cases are fantastic.

I try to root this stuff in the passage from Kant (transcendental psychology) to Hegel (metaphysical sociology) and their successors, both because these are my preferred terms, but because it's the best way of uniting the various strands of the discourse/dialectic I've found.

But the key debate in C20th analytic philosophy of logic, language, and mind, is that between Carnap and Quine over the viability of the 'analytic', which Brandom essentially sees reflected in Kant/Hegel and Sellars/himself. It's an extraordinarily subtle problem.

If you want to see an echo of this debate, directly relevant to @AlldrittOwen's worries about the difficulty of deliberate conceptual change, check out this exchange between me and @lastpositivist regarding conceptual evolution and the destiny of 'human': http://sootyempiric.blogspot.com/2017/07/afro-pessimism-and-instantiation-thesis.html

I think I have two basic positions here:

1. We cannot get rid of the (transcendental) psychology of concepts entirely, as individuals must have internalised heuristics/rules that make inference (computationally) tractable. This makes mathematics the optimal test case.

1. We cannot get rid of the (transcendental) psychology of concepts entirely, as individuals must have internalised heuristics/rules that make inference (computationally) tractable. This makes mathematics the optimal test case.

2. The features which makes mathematical concepts a perfect test case (dialectical stability, computational tractability, and inter-translatability) also distinguish them from other concepts, and so we cannot simply treat empirical concepts as 'the same, but moreso'.

I take this to be the properly Kantian position: the semantics of mathematical and empirical terms are in some strict sense dual to one another, and this duality articulates the relation between them (e.g., mathematics → physics, and physics → mathematics). This is deep logic.

However, this is where the tension between Kant and Hegel becomes most apparent, as the transcendental logic that expresses our connection to (mathematical/empirical objects) must be embedded in a deeper dialectical logic that envelops them both. Literally deeper logic.

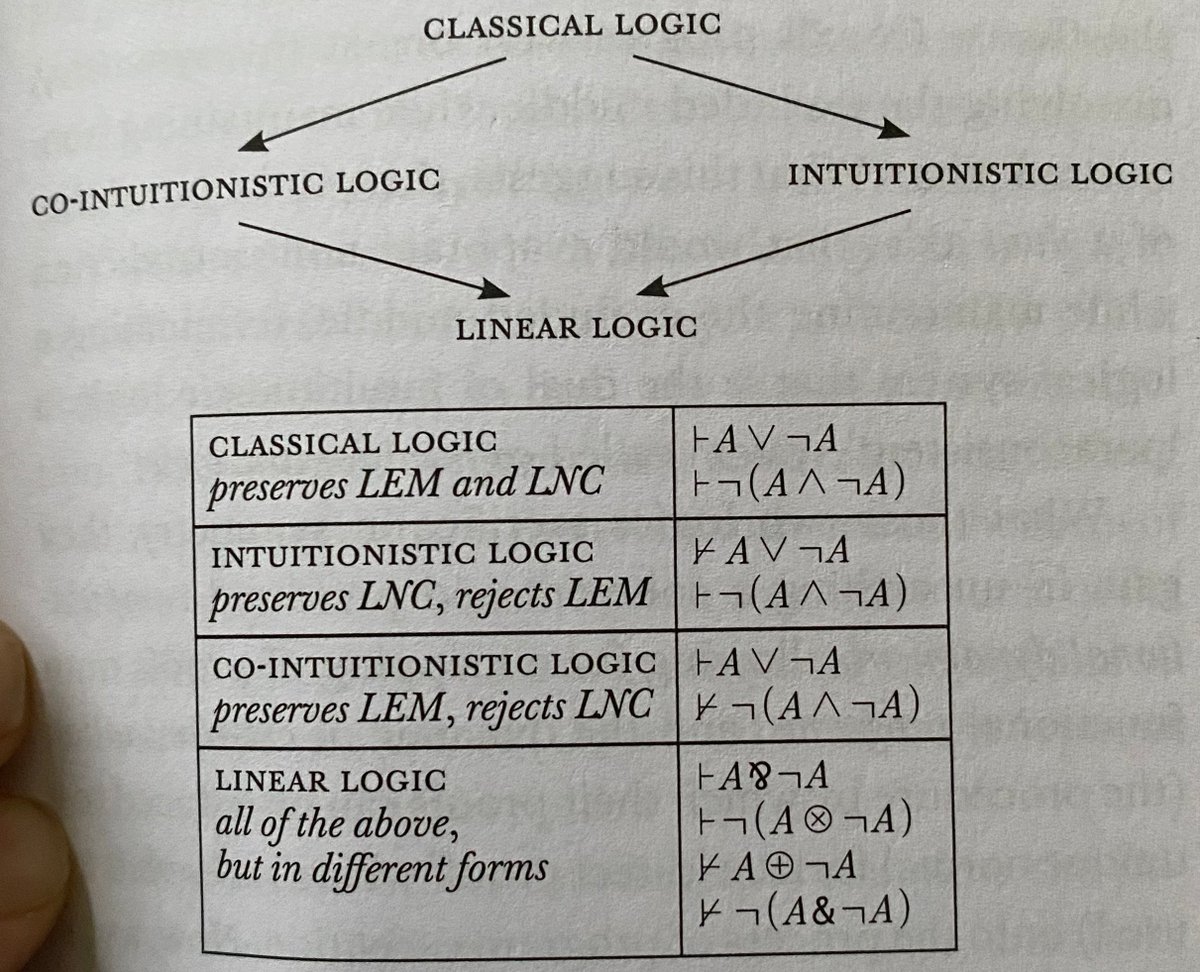

If you want a very limited model of this embedding, look at the way in which classical logic (general) splits in two, into intuitionistic (mathematical) and co-intuitionistic strands (empirical), and how these embed into the substructural framework of linear logic (dialectical).

This is the diagram, originally due to Samuel Troncon ( http://samuel.troncon.name/ ), but introduced to me by @PETARDHOISTER in person, and via her excellent translation of Zalamea's Synthetic Philosophy of Contemporary Mathematics:

This is also where the debate between myself and @lastpositivist segues into my debate with @NegarestaniReza, who has synthesised Hegel and Carnap's logical programs in a way that bypasses my own Kantian defence of transcendental logic and analyticity. We'll see how it goes.

My thought has evolved quite a bit since my 'Essay on Transcendental Realism', precisely because I've learned more about logic and mathematics, but you can still see the foundations of all these ideas therein. The great bastard child of my corpus: https://philpapers.org/rec/WOLEOT-2

There my concern with the 'generic' logic appropriate to talking about things like fictional objects ('Harry Potter') is really a concern with the relation between 'general logic' and the dialectical logic in which it and its mediating transcendental logics are embedded.

Linear logic is something like the logic of fictions, but this is hard to appreciate at the propositional level, because precisely what we're interested in is the connection between sense and reference articulated by the relation between predicates, objects, and types.

The closest I've come to making this case properly is in my still unfinished extended version of 'Castalian Games', in which I try to embed Sellars and Brandom's account of the game of giving and asking for reasons (GOGAR) into the philosophy of games by way of Girard's ludics.

It's dense, unwieldy, and unfinished, but it is available to view ( https://deontologistics.files.wordpress.com/2019/11/gbg.pdf ). It also relates these issues to the Nietzsche/Hegel relationship by framing everything through Hesse's Glass Bead Game, which is all about that relationship.

I've always thought of Castalian Games as my 'French book'. It's not just that it got brutally cut down (by ~10K) because of the budget for translating it into French, but that I was trying to do things you're only really allowed to do if you're French.

If you're English and you right a book about philosophy of games, philosophy of language, aesthetics, logic, and mathematics all at once that's framed as a reading of a modernist novel, there's just no where to put it. If I ever finish it, I'll make sure it's published in France.

To return to the topic from which I started, I'm sympathetic both to @AlldrittOwen's worries, even if I'm also sympathetic to neopositivists and others who want to assert their right to ditch conceptual history and engineer concepts at will. Where do we go from here?

Well, this is where we return to another recent thread: https://twitter.com/deontologistics/status/1356949507297210368?s=20

I think the answer is that we reserve the right to experiment with our expressive devices and the underlying inferential machinery as much as we like, as long as we also recognise the difficulty or doing so, and that experimenting means 'creatively failing' in a variety of ways.

This is where pluralism remains important, because none of us can honestly say what the best way to re-engineer any aspect of our conceptual scheme is, let alone all of it, because the very idea of a best way is completely incoherent here.

The best we can hope for is to start (or reboot) a bunch of distinct research programs that we make compete in dialectically healthy ways. Yet when it comes to articulating what such dialectical health entails, we may find Hegel waiting for us, around every corner, laughing.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter