Pondering the story of how my 3 books (a literary biography of Nabokov, a global history of concentration camps, & ICEBOUND, an Arctic story from 400 years ago) all rose out of my search for the King of Zembla, which began in 2008. The Zembla Trilogy. Would you like to hear more?

All right! So I'll tell the story. But I'll want to pull together some neat images for it, so it won't be tonight. I'll try to post it this weekend...

As promised, here we go! (It will be a long thread--feel free to mute me...)

I want to tell you how I came to write ICEBOUND, in which William Barents & 16 Dutchmen get stranded on Arctic Nova Zembla more than 400 years ago. It's the story of my search for the King of Zembla, which ties my 3 books together & in the end took me all the way to Nova Zembla.

In early 2008, I was reading Nabokov's PALE FIRE, in which the delusional narrator believes he's the exiled ruler of a kingdom called Zembla. I got fascinated by Zembla, because Nabokov seemed to be winking at something outside the book itself. I decided to investigate.

Nabokov scholars knew that there were islands north of the Russian mainland called Nova Zembla (in Russian: Novaya Zemlya, or "New Land"). In his autobiography SPEAK MEMORY, Nabokov writes of his great-grandfather going there and the family legend of a Nabokov's River there.

But Zembla went farther back in Nabokov's catalog than SPEAK, MEMORY or PALE FIRE. Nova Zembla came up in his New Yorker poem from 1942, "The Refrigerator Awakes." He had been thinking about this part of the world two decades before PALE FIRE. https://genius.com/Vladimir-nabokov-the-refrigerator-awakes-annotated

While Nabokov worked on PALE FIRE, I discovered, Nova Zembla had been covered, dramatically, in several front-page stories in the newspaper he read. Those stories were about the Russians setting off the Tsar Bomba, the largest man-made explosion in history (then or since).

That bomb may have been a tsar, but was no king in any real sense. I continued my search. I found a 1958 book by a former American prisoner in the Gulag, who managed to sneak out a postcard alerting the West about his detention. Eisenhower successfully demanded his release.

In a memoir of his experiences, this man, John Noble, made mention of Novaya Zemlya (Nova Zembla), saying it was the legendarily worst site of the Gulag, the place to which they sent the career criminals and worst of the worst. But there was still no king.

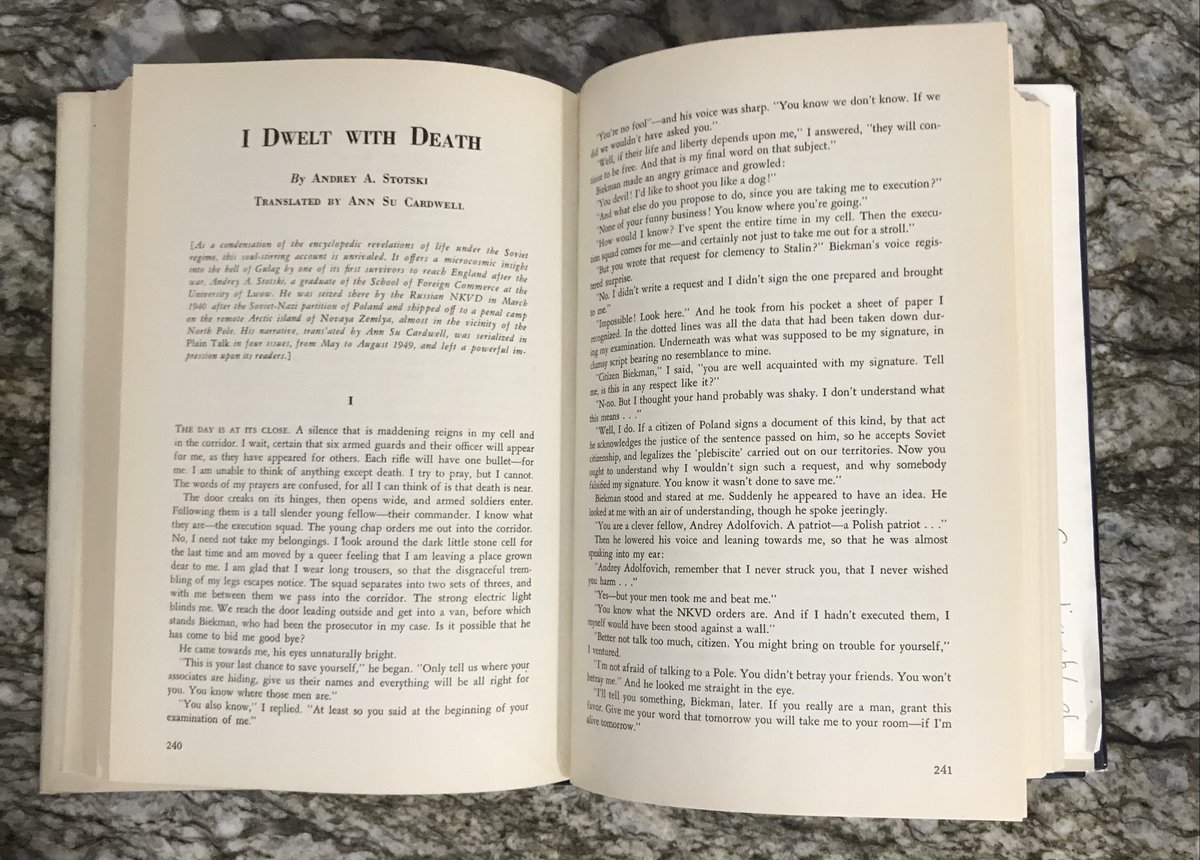

I found reference after reference in Western sources that recorded former detainees identifying Novaya Zemlya as an iconic Gulag site: from this Polish prisoner released to fight the Germans, and in other terrifying accounts passed on by refugees.

Nabokov had made mention of Gulag and pre-Gulag camps in more than one book. And the mad king of Zembla in PALE FIRE—a man we find out at one point is really a Russian refugee—talks about "the frozen mud and horror" in his heart.

With all the stories of Gulag camps on Nova Zembla, I wondered 1) was it really the site of some of the most horrific camps? 2) Did Nabokov know about these stories? 3) Did he mean the mad king to be an escapee from the Gulag? and 4) (Still!) Was there ever a real king of Zembla?

I won't focus on #1 or #3, which are in my first book. But the search for #1 led me from Prague into the Czech countryside (in a car with a former interpreter of Schwarzenegger's & her unhappy ex-husband) to meet with a man identified as a former Gulag prisoner from Nova Zembla.

And as to question #2, I went further and further back. The first story I could find about prisoners sent by the Bolsheviks to Nova Zembla (Novaya Zemlya) predated the existence of the USSR itself. It appeared in the Times of London and the New York Times in August 1922.

It was known that Nabokov's brother, Sergey, had died at Neuengamme, a Nazi camp. I traveled there for research in 2011. I began more research about pre-WWII camps mentioned by Nabokov, how the concept of concentration camps first emerged, and how humanity got to Auschwitz.

I couldn't find an English-language history of this idea. I read one in French, but it had limitations. So I kept researching after I finished the Nabokov book. In time, this work would become ONE LONG NIGHT, my global history of concentration camps from the 1890s to the present.

But I still hadn't found a real-world King of Zembla! I went back past the 20th century into the 19th, when expeditions to Nova Zembla were attempted, with one finally reaching the ruins of a cabin built there in the 1590s by a crew of Dutchmen.

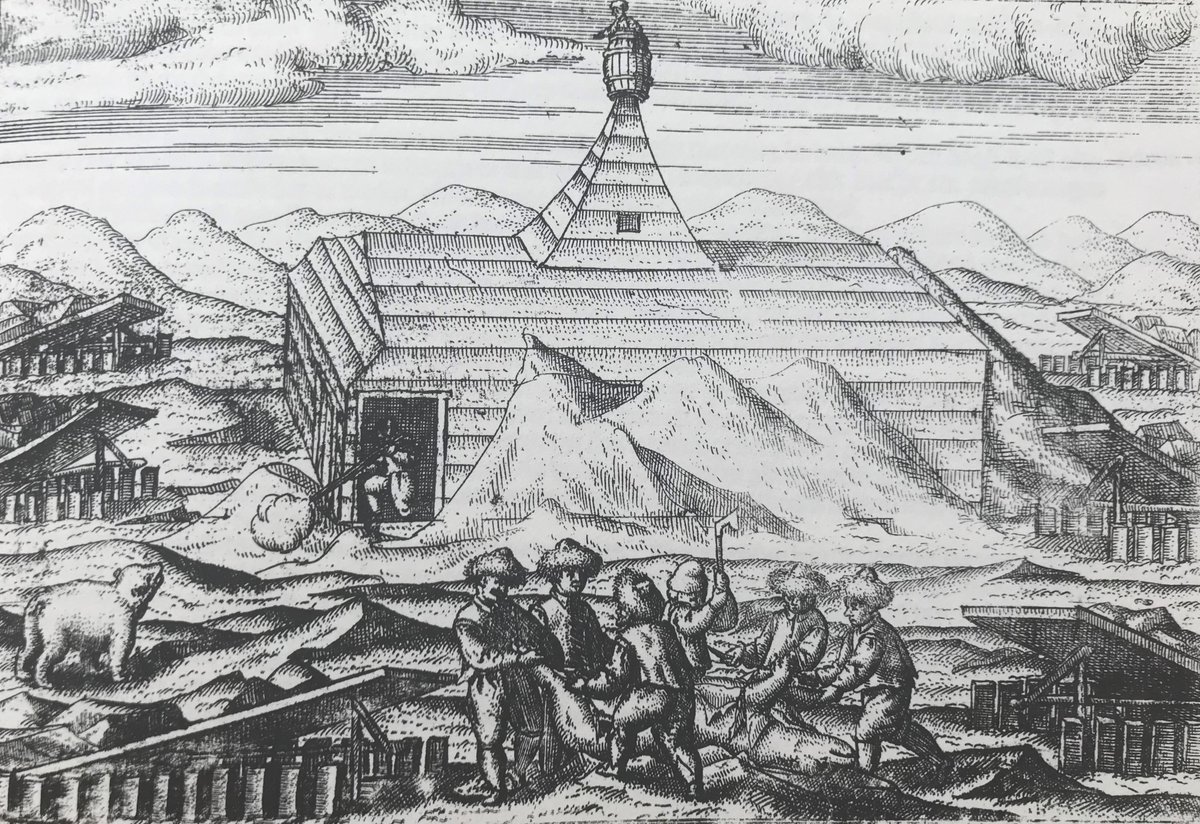

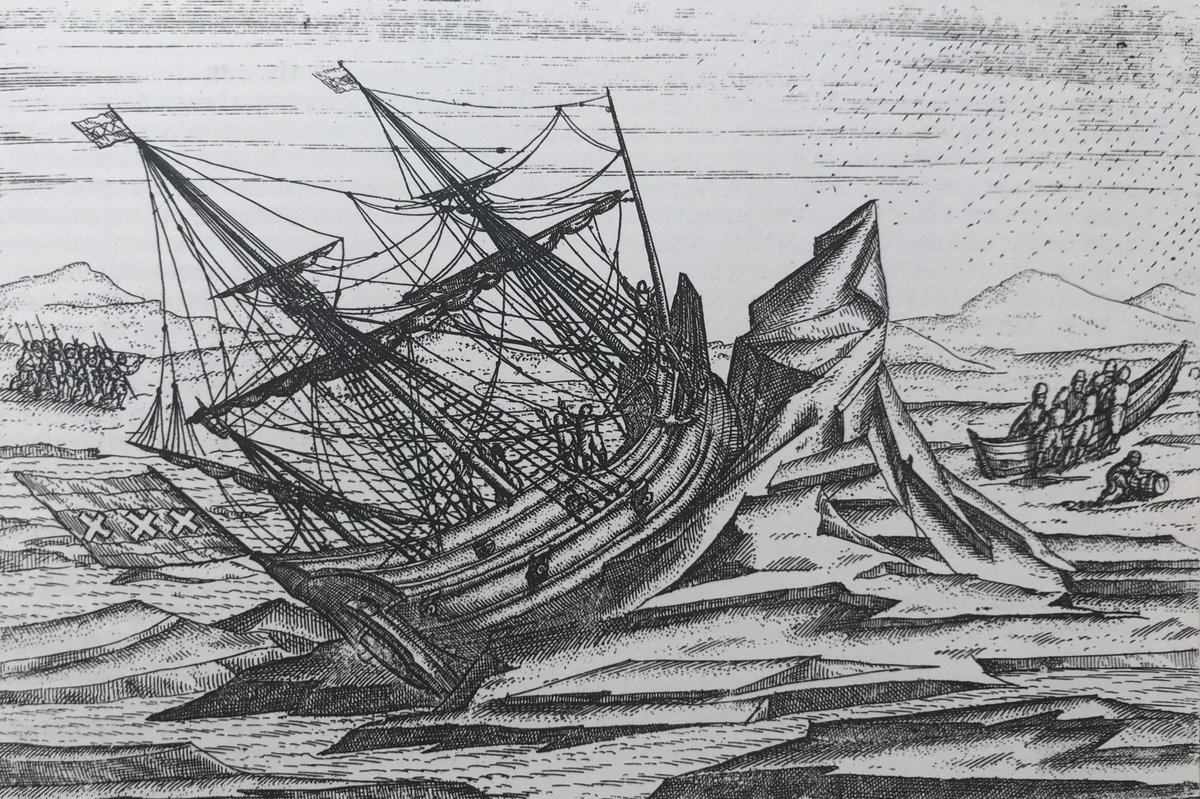

The Barents Sea west of Nova Zembla is today named for one of those Dutchmen: William Barents (Willem Barentsz in his native tongue). He was stranded for the winter of 1596 on the northeastern side of Nova Zembla at Ice Harbor when the sea turned solid all around.

The more I read about them, the more I pondered why we in the US know so many stories of attempts to find a Northwest Passage but so little about the search for a northeastern route to China. In part, of course, it's geographical proximity, but there are some amazing stories.

As for Barents, an official account of his voyages was translated into English centuries ago. Another book-length tale was written by Rayner Unwin, the man who, as a child, recommended his father greenlight the MS for THE HOBBIT and later himself acquired THE LORD OF THE RINGS.

But important things were missing from both. I couldn't find an English-language telling of the *whole* story, from polar bears to mutiny, keelhauling, smothering ice, astronomical wonders, & scurvy eating away a little more at the men each day. I began to think I might write it.

By now, you're probably wondering, "Wait! What happened to the King of Zembla?" Had Nabokov been thinking of anything from the real world when he created his mad king in PALE FIRE?

I have to take a break to do something! But I'll return before too long...

Nabokov had likely read Barents' story—not only because of his long interest in Nova Zembla but also because he knew about & recommended expedition narratives from the society that republished and annotated the original English-language translation of Barents' voyages.

Looking through the narrative of Barents' third expedition, I found that just after New Year's in 1597, the men hunkered inside their cabin surrounded by snow & ice. They suffered terribly. They had no idea if they would survive the winter or not, but they wanted to have a feast.

Back home, Twelfth Night was a huge event. Tradition held that the Wise Men were about to arrive to see the newborn Christ. To celebrate, revelry and drinking were embraced. It was understood the world would be turned upside down. Social positions were upended for one night.

People would draw lots, tickets, or cards, & randomly find themselves assigned to roles for the evening. The servant in the house might reign over everyone. The head of the house might become a servant. It drew as much from Roman Saturnalia & carnival as any Christian tradition.

Facing a winter of thinning rations ahead and more than an inch of ice on the inside of their cabin, the men stranded on Nova Zembla wanted to try to replicate a little of the gaiety from Twelfth Night at home. Their captain said they could hold a feast.

Given two pounds of meal that had been intended for other purposes, they made fried cakes. They each got a biscuit, and drank wine that they had saved up. And they drew lots, much as they would have in Amsterdam. By chance alone, the ship's gunner became their king.

And so for one night in January 1597, Nova Zembla, with no indigenous population wintering on its shores, had a king. I had found the king of Zembla and the story for what would, more than a decade later, become ICEBOUND.

When Barents' story made its way back to the Netherlands (I won't tell you how here), it would be translated into several languages. And William Shakespeare would hear of the amazing overwintering of these Dutchmen on Nova Zembla.

And just as the Dutchmen had made their Twelfth Night, Shakespeare would, less than five years later, create a "Twelfth Night" of his own, which also features a shipwreck and the world turned upside down.

When one character offends another in the play, Shakespeare writes that he has "sailed into the north of my lady's opinion; where you will hang like an icicle on a Dutchman's beard..."

Barents et al. were so famous in that moment, Shakespeare could refer to them in passing without mentioning them by name or noting their "Twelfth Night" feast—the feast at the heart of what I had been looking for, the ship's gunner who had for one night been King of Nova Zembla.

I would end up sailing to Nova Zembla myself to the ruins of their cabin. I would touch the relics that they'd handled more than 400 years ago. And all the time, I would remember that gunner freezing in his bed, going from darkness to moonlight to darkness, all polar night long.

And that's the story of how I set out to find the King of Zembla and ended up writing a Zembla trilogy. FIN.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter