Our latest publication revisits a well-known problem: reporting of relative effect estimates without absolute effects in journal publications of clinical trials:

https://ebm.bmj.com/content/early/2021/01/31/bmjebm-2020-111489

on this issue

on this issue

("nah, show me the findings": )

https://ebm.bmj.com/content/early/2021/01/31/bmjebm-2020-111489

on this issue

on this issue("nah, show me the findings": )

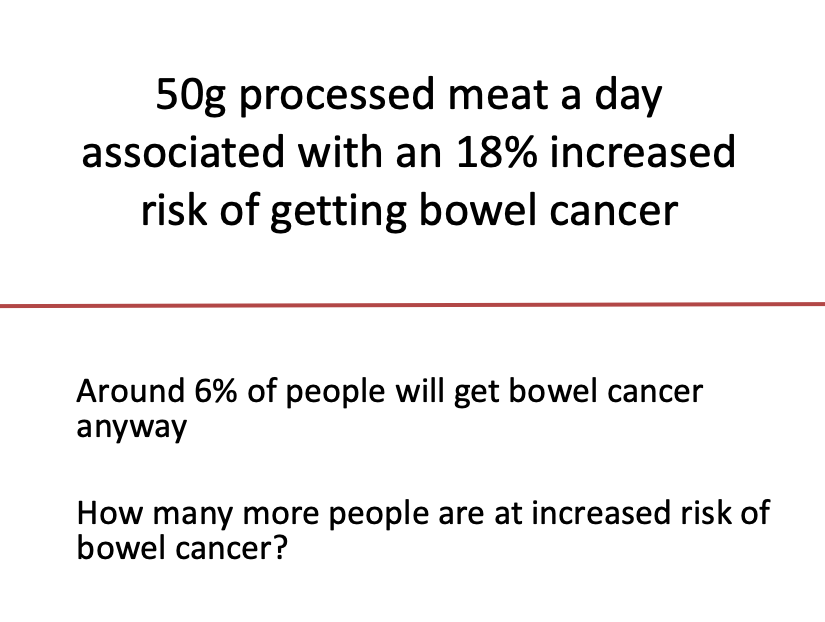

First an intro to the problem. A practical example is probably best here. Take a look at the image. How many more people are at increased risk bowel cancer?

I'll be nice by making it multiple choice:

'1' =  If you chose '1%' then you were close - I wanted to turn %'s into actual numbers of people as this is generally better understood by most people when communicating risk. Here's the math:

If you chose '1%' then you were close - I wanted to turn %'s into actual numbers of people as this is generally better understood by most people when communicating risk. Here's the math:

6% = 6 in 100

18% of 6 = 0.18 * 6 = 1.08

6 + 1.08 = 7.08 = 1 more person (in 100)

If you chose '1%' then you were close - I wanted to turn %'s into actual numbers of people as this is generally better understood by most people when communicating risk. Here's the math:

If you chose '1%' then you were close - I wanted to turn %'s into actual numbers of people as this is generally better understood by most people when communicating risk. Here's the math:6% = 6 in 100

18% of 6 = 0.18 * 6 = 1.08

6 + 1.08 = 7.08 = 1 more person (in 100)

I've shamelessly stolen this exercise from @d_spiegel - who incidentally coined this the "number needed to eat", genius!

It illustrates the problem of using relative risk estimates ALONE that we see almost daily in media reports of health research. 18% sounds a lot worse than 1%

It illustrates the problem of using relative risk estimates ALONE that we see almost daily in media reports of health research. 18% sounds a lot worse than 1%

Whenever you see " [X] increases risk of disease/health outcome [Y] by...", always ask yourself "What is the risk of [Y] without [X]?". This risk (Y without X) is also known as the baseline risk which is how often (or the 'likelihood') disease/health outcome Y occurs anyway.

Baseline risk for, or the likelihood of, many diseases/health outcomes is actually quite low. Any RELATIVE increase, even a large one, most likely moves a low risk to still a low risk. The difference between 'low risk to low risk' is called the absolute risk or risk difference

Sometimes low risk goes to high risk (or vice-versa), but it's not that common.

Here's a useful read on all this: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63647/

Here's a useful read on all this: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63647/

Because we humans appear to be impressed by big numbers, & because humans produce health research & run journals within which this research is published, we see the bigger relative risk estimate reported way more often than its smaller absolute cousin.

Wait. That's not the only problem. Because the human brain is quite easily fooled (see work by Daniel Kahneman & Amos Tversky), we can use the relative & absolute risk estimates to influence our interpretation and our (health care) decisions.

Oh yes. Say hello to "Mismatched framing" = the benefits are presented in relative terms, while the harms or side effects are presented in absolute terms = the benefits look bigger and the harms look smaller.

Doesn't take much to see why this is so tempting.

Doesn't take much to see why this is so tempting.

Want more proof of the importance of this issue? Take a look at these studies which show the influence on patient and health professionals decisions when presented with relative or absolute risk estimates:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18631406/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7909875/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1443954/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18631406/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7909875/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1443954/

Many have argued that this framing is bad science, some even calling it immoral:

https://www.healthnewsreview.org/2010/12/leading-risk-comm-guru-gigerenzer-argues-that-absolute-risk-communication-is-a-moral-issue/

These same folk have sought to find solutions to the problem.

https://www.healthnewsreview.org/2010/12/leading-risk-comm-guru-gigerenzer-argues-that-absolute-risk-communication-is-a-moral-issue/

These same folk have sought to find solutions to the problem.

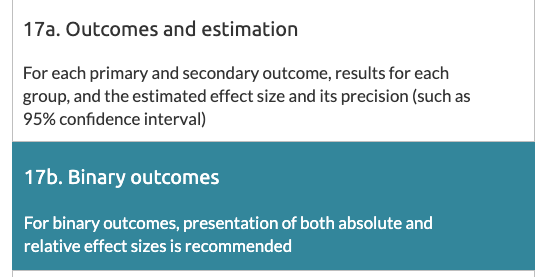

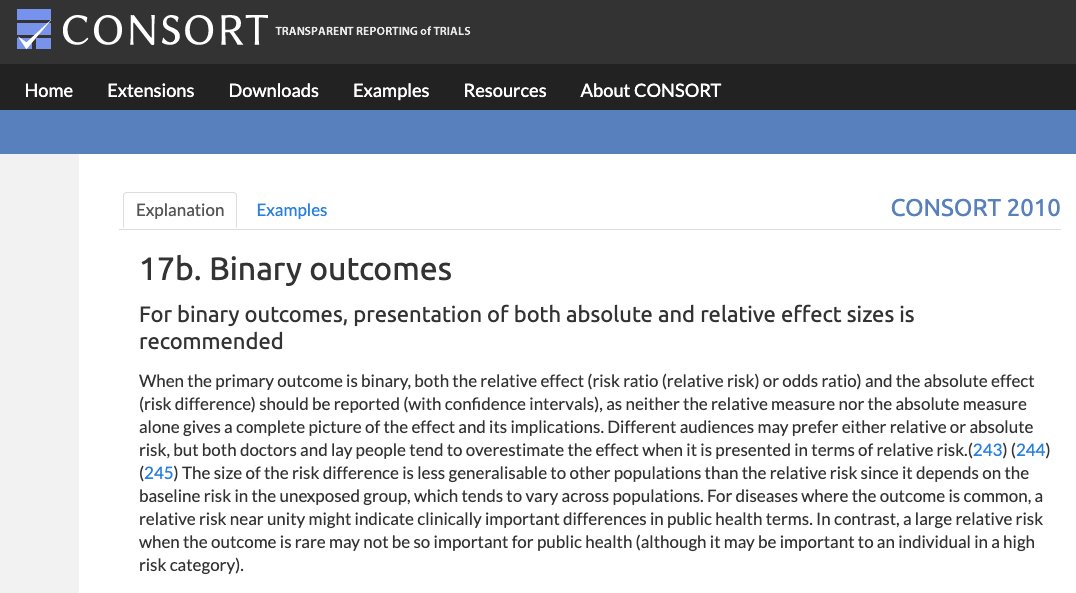

One solution is setting standards & consensus on the reporting of relative & absolute risk estimates in published clinical trials. I give you the CONSORT (CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting) statement:

http://www.consort-statement.org/

Conceived in 1993, born in 1996, updated 2010

http://www.consort-statement.org/

Conceived in 1993, born in 1996, updated 2010

The statement is an agreed minimum standard of key design/methods for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) + how they should be reported. Item 17b relates specifically to reporting of relative & absolute effect estimates & a measure of their uncertainty (=95% confidence interval)

Having developed the tool, the creators worked hard to engage journal editors to endorse it. Here they were successful. Over 600 journals and editorial organisations now endorse CONSORT: http://www.consort-statement.org/about-consort/impact-of-consort

Job done then!

Well...

Job done then!

Well...

You'd think that journal endorsement would help with our framing problem. Even more so if a journal requires authors to submit a completed CONSORT checklist, marking down exactly where in their manuscript they meet each item, including item 17b.

That's what we assessed.

That's what we assessed.

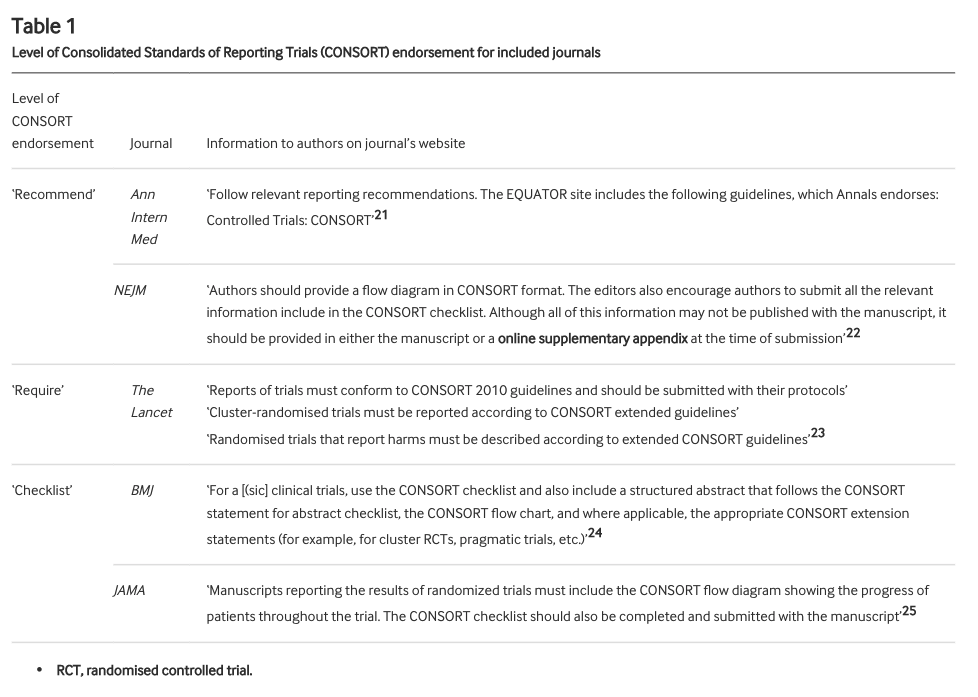

We looked at all RCTs published in @TheLancet @NEJM @bmj_latest @JAMA_current and @AnnalsofIM in 2019 that reported the type of outcome* where the CONSORT statement recommends reporting both relative & absolute risk.

*binary outcomes (e.g. death, heart attack, hospitalisation)

*binary outcomes (e.g. death, heart attack, hospitalisation)

These journals all endorse the CONSORT statement to differing degrees. We defined the level of endorsement in 3 categories: "recommend" (ok), "require" (good), "checklist" (best). As well as overall adherence to item 17b, we checked how level of endorsement related to adherence

So what did we find? ("FINALLY!").

258 RCTs were included.

Of these, 53 adhered fully to item 17b. That's 20.5% (95% CI 15.8% to 26.0%) or 1/5 or 1 in 5.

Meaning 80% or 4/5 or 4 in 5 did not report both relative & absolute effect estimates as recommended.

258 RCTs were included.

Of these, 53 adhered fully to item 17b. That's 20.5% (95% CI 15.8% to 26.0%) or 1/5 or 1 in 5.

Meaning 80% or 4/5 or 4 in 5 did not report both relative & absolute effect estimates as recommended.

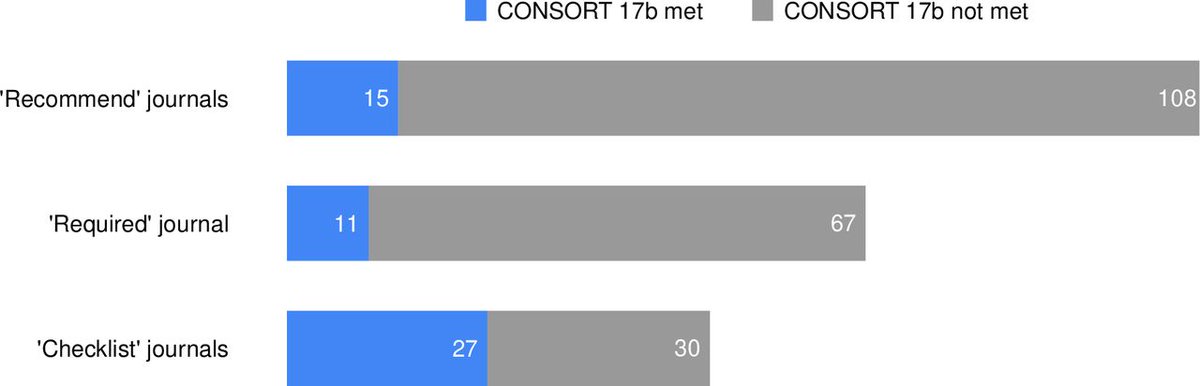

What about the breakdown by level of endorsement?

Journals that only "recommend" = 15 out of 123 (12.2%, 7.0% to 19.3%) adhered

Journals that "require" = 11 out of 78 (14.1%; 7.3% to 23.8%)

Journals where "checklist" = 27 out of 57 (47.4%, 34.0% to 61%)

Checklist = better

Journals that only "recommend" = 15 out of 123 (12.2%, 7.0% to 19.3%) adhered

Journals that "require" = 11 out of 78 (14.1%; 7.3% to 23.8%)

Journals where "checklist" = 27 out of 57 (47.4%, 34.0% to 61%)

Checklist = better

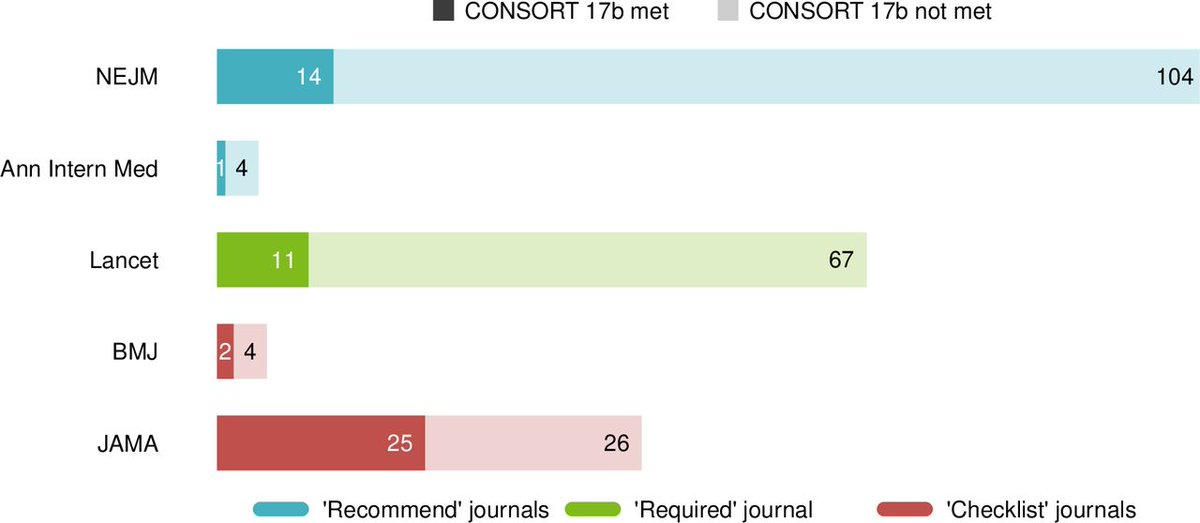

Ah, but what about individual journal's you say:

Recommend = NEJM and Ann Int Med

Require = Lancet

Checklist = BMJ and JAMA

Recommend = NEJM and Ann Int Med

Require = Lancet

Checklist = BMJ and JAMA

Even in journals requiring completion of the checklist, over half did not report relative and absolute risk estimates in accordance with the CONSORT statement.

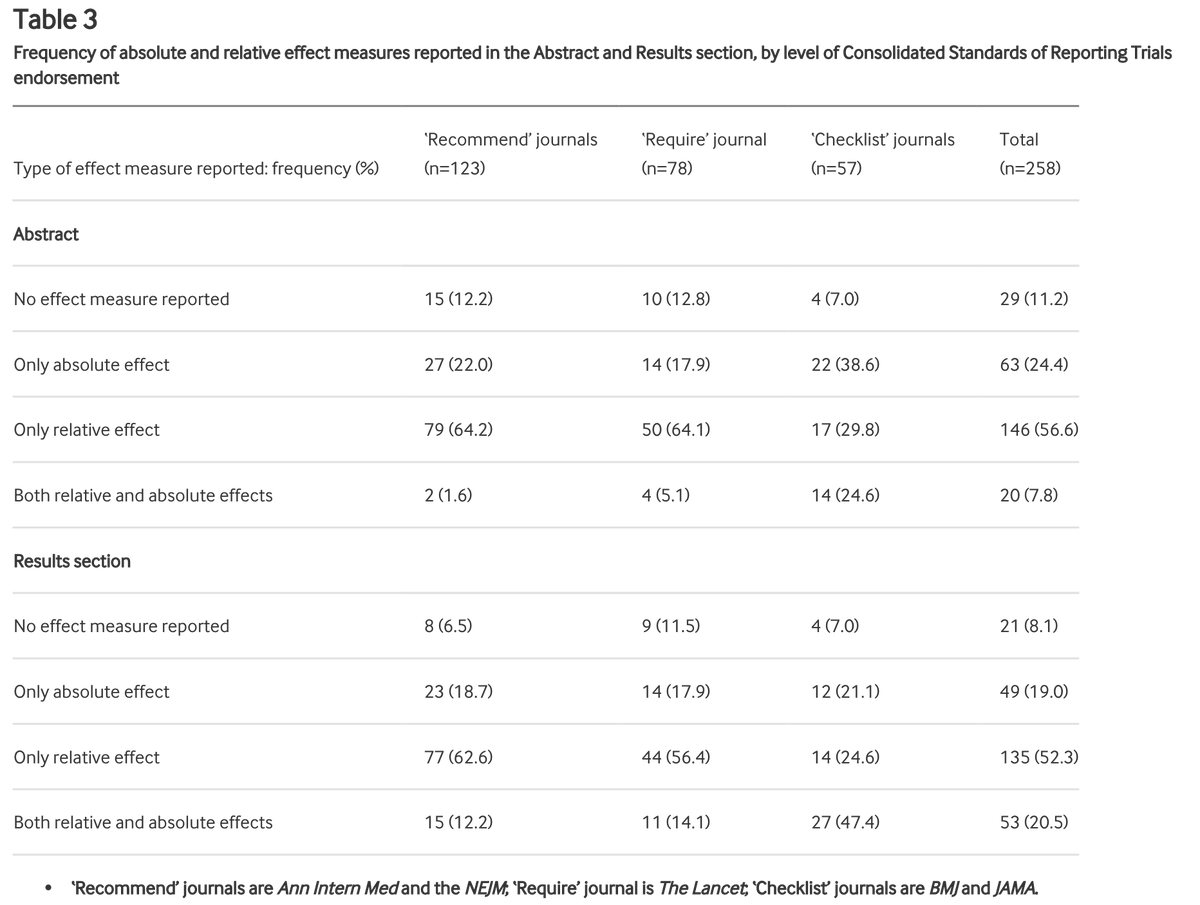

We also looked at reporting in the abstract section:

Relative effects only were reported in 64.6% of articles published in recommend journals. Both effects were reported in only 1.6% of articles in these journals

This compares with 29.8% and 7.8% in checklist journals.

Relative effects only were reported in 64.6% of articles published in recommend journals. Both effects were reported in only 1.6% of articles in these journals

This compares with 29.8% and 7.8% in checklist journals.

It's Friday. I need a drink. You deserve one too if you followed this far. TBC....

Ok. Where were we? Oh yes, ~80% of RCTs with a binary outcome published in 2019 in the top 5 medical journals did not adhere to item 17b of the CONSORT statement (= reporting both relative & absolute risk estimates)

Despite all the journals endorsing CONSORT to varying degrees

Despite all the journals endorsing CONSORT to varying degrees

The question then is why?

Do the findings reflect administrative or technical problems with adhering to the reporting guideline?

Are authors attempting, consciously or otherwise, to inflate or deflate treatment effect estimates?

Do the findings reflect administrative or technical problems with adhering to the reporting guideline?

Are authors attempting, consciously or otherwise, to inflate or deflate treatment effect estimates?

The best way to get an idea of this is to ask them, right?!

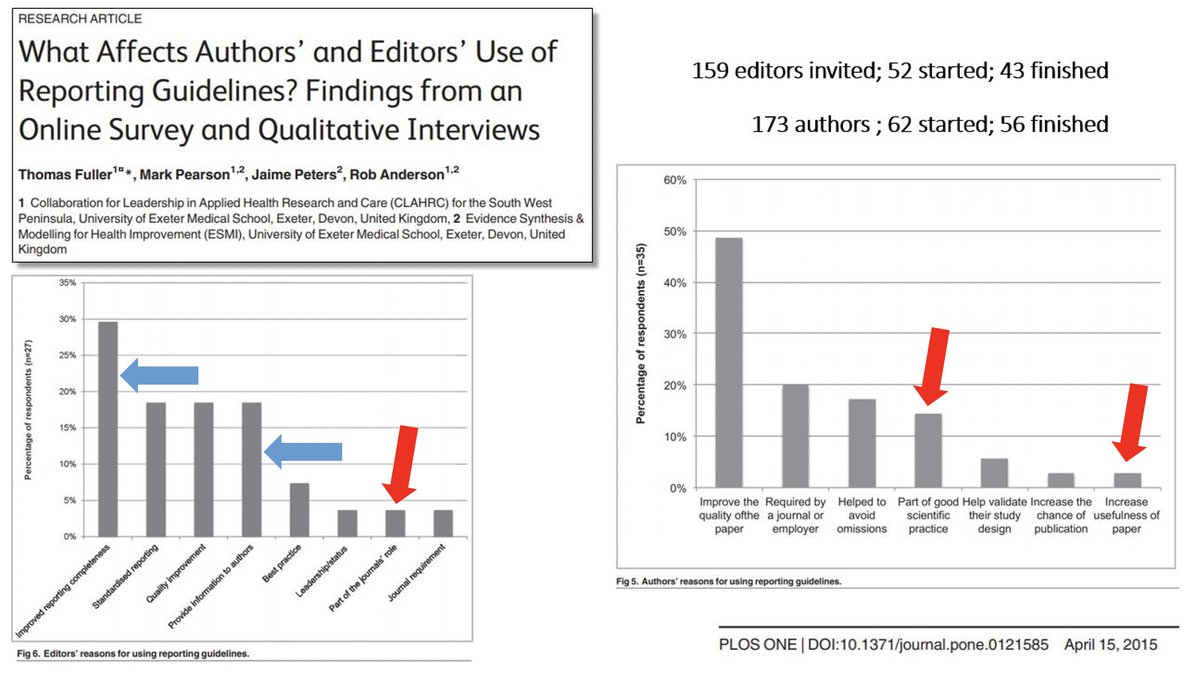

That's what Fuller et al (2015) did: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0121585#

Key findings:

~4% of journal editors felt it was the journal's role to use reporting guidelines. ~4% also felt they are a journal requirement.

Worrying.

That's what Fuller et al (2015) did: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0121585#

Key findings:

~4% of journal editors felt it was the journal's role to use reporting guidelines. ~4% also felt they are a journal requirement.

Worrying.

As for authors, ~13% felt reporting guidelines were part of good scientific practice; ~2% felt they improve the usefulness of their paper!

Equally worrying.

Equally worrying.

So some editors & authors have a stance indicating we shouldn't be surprised with poor adherence to reporting guidelines

Fuller et al was a small sample - ?? re: representativeness

Another reason is a failure to recognise the problem (of poor reporting) even when made aware

Fuller et al was a small sample - ?? re: representativeness

Another reason is a failure to recognise the problem (of poor reporting) even when made aware

See @bengoldacre and the @COMPare_Trials team on this (and many another troubling editorial/author responses) in relation to outcome reporting: https://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13063-019-3172-3

Spin bias is another possible reason:

https://catalogofbias.org/biases/spin-bias/

Editors and peer-reviewers, knowingly and unknowingly, may facilitate all of these.

https://catalogofbias.org/biases/spin-bias/

Editors and peer-reviewers, knowingly and unknowingly, may facilitate all of these.

Journal editors who endorse CONSORT might think this means it is being adhered to. Including item 17b.

A recent example highlights the difficulty in unknowingly facilitating the problem. I give it not to call anyone out, but to illustrate why we need better systems.

A recent example highlights the difficulty in unknowingly facilitating the problem. I give it not to call anyone out, but to illustrate why we need better systems.

In a Sept 2020 episode of his podcast, the EIC of @JAMA_current, Dr Howard Bauchner, was discussing an editorial on communicating treatment effects with its authors including @dr_dmorgan (it's a great editorial & I highly recommend you read/listen) https://edhub.ama-assn.org/jn-learning/audio-player/18539849

At 13:22 in, Dr Bauchner states: "...we never allow original research to report just relative differences..."

Whilst RCTs in JAMA had better adherence to item 17b, we found 11 of 51 (22%) reported only relative effects in the results section & 15/51 (25%) in the abstract.

Whilst RCTs in JAMA had better adherence to item 17b, we found 11 of 51 (22%) reported only relative effects in the results section & 15/51 (25%) in the abstract.

Our task was made hard by ambiguity in author instructions in relation to their responsibility for CONSORT guideline adherence.

This has been highlighted by others: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1408-z

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-60

Standardised instructions remains an easily resolvable issue.

This has been highlighted by others: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1408-z

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-60

Standardised instructions remains an easily resolvable issue.

In terms of other things we can do:

Some have called for journal editors to insist authors provide, with guidance if needed, absolute effects adjacent to corresponding relative effect sizes, with failure to do so resulting in no publication: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38985.564317.7C

Some have called for journal editors to insist authors provide, with guidance if needed, absolute effects adjacent to corresponding relative effect sizes, with failure to do so resulting in no publication: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38985.564317.7C

One of these was Lisa M Schwartz, who was an advocate for clear communication of medical risks and spent an amazing career doing great work to highlight and help solve problems like framing. You can read more about her and her great work here: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)30150-3/fulltext

No publication is probably at the extreme end of measures (though we may well have arrived there).

Another issue we had was we could not ascertain how authors submitting to "checklist" journals (BMJ, JAMA) were answering item 17b.

Another issue we had was we could not ascertain how authors submitting to "checklist" journals (BMJ, JAMA) were answering item 17b.

These journals don't provide completed checklists as part of the supplements. Why not? Not much to add is it?

We recommend as a minimum that all journals require submission of a completed checklist & that these be published in the supplementary material for readers to review.

We recommend as a minimum that all journals require submission of a completed checklist & that these be published in the supplementary material for readers to review.

None of the journals provide information on their processes for reviewing adherence to CONSORT to ensure accuracy etc. Again, why not? It's likely because there isn't much of a review process. Ok. Be transparent about that. It's better than the current facade.

The @EQUATORNetwork provides an avenue for journal editors to share case studies of their implementation & compliance strategies: https://www.equator-network.org/toolkits/using-guidelines-in-journals/case-studies-how-journals-implement-reporting-guidelines/

Former director of the UK HTA, Prof Hywel Williams, shows us how it's done: https://www.equator-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/3242_Clinical+Trial+Journal+of+Investigative+Dermatology+final+EQ.pdf

Others could too.

Former director of the UK HTA, Prof Hywel Williams, shows us how it's done: https://www.equator-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/3242_Clinical+Trial+Journal+of+Investigative+Dermatology+final+EQ.pdf

Others could too.

It's 14 years since Lisa Schwartz called for improvements in effect estimate reporting in journals. It appears we are 14 years and still waiting.

It will be 3 yrs this June since the death of Doug Altman who led the way on all of this (a great article on his legacy from his colleagues:

https://twitter.com/GSCollins/status/1357630606411186177?s=20)

It would be a fitting honour to them (& many others) to finally walk-the-walk & not just talk-the-talk.

FIN

https://twitter.com/GSCollins/status/1357630606411186177?s=20)

It would be a fitting honour to them (& many others) to finally walk-the-walk & not just talk-the-talk.

FIN

One last one to thank my co-authors @carlheneghan and the 3 medical students from @OxfordMedSci who did lots of the heavy lifting as part of their research placement @OxPrimaryCare

Sterling effort.

Sterling effort.

Unroll @threadreaderapp

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter