THREAD. There’s so much water in the fields at present - fields are floating in water. Here in the east of England it’s a practical lesson explaining so much about land use before under-field drainage began in the 17thC.

2. Seasonal springs are suddenly bubbling with water ...

3. and everything is sodden underfoot.

4. This was land that could never have been ploughed before under-field drainage was introduced. Dig down more than 6” here and the hole fills with water. How does that work?

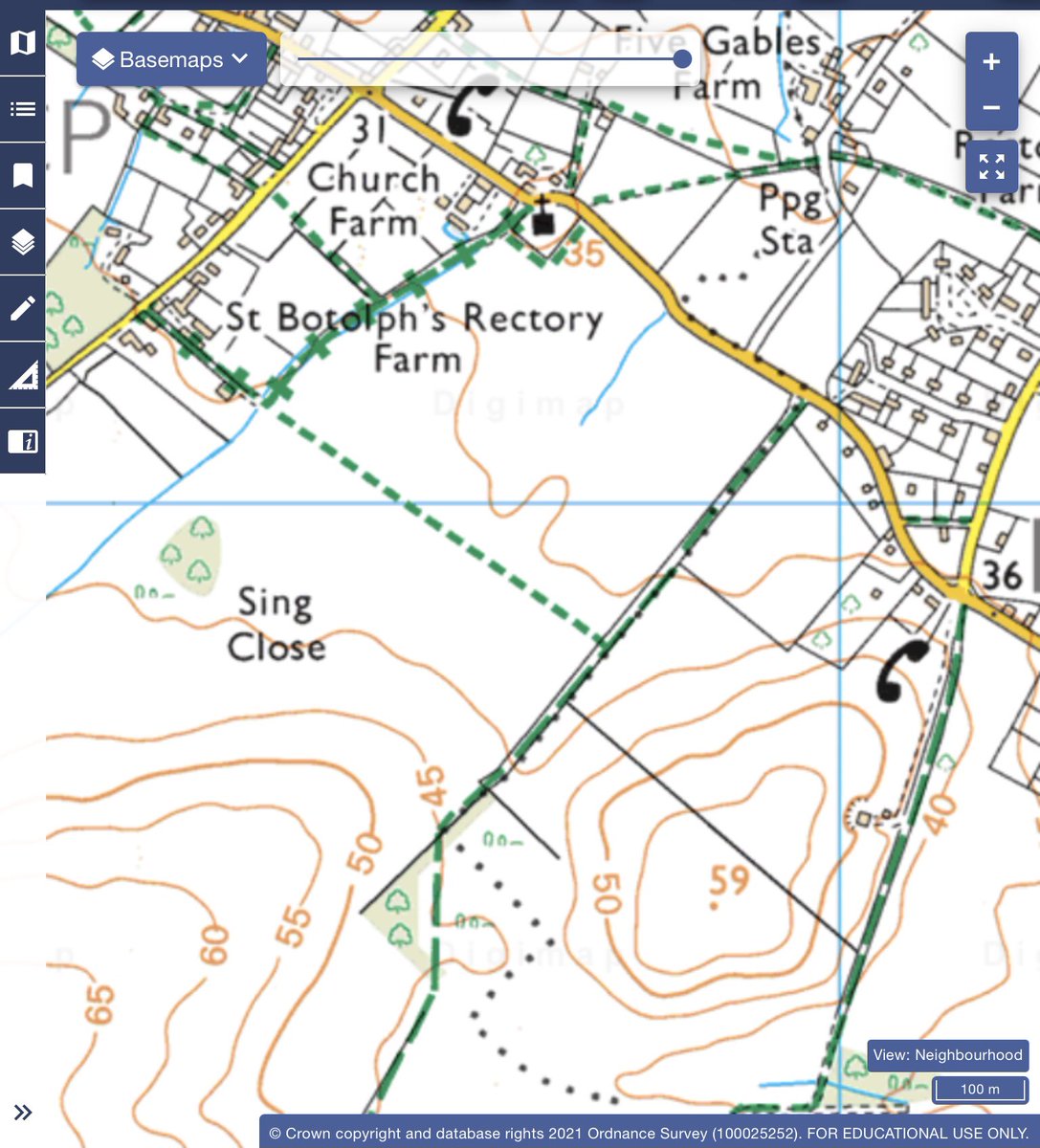

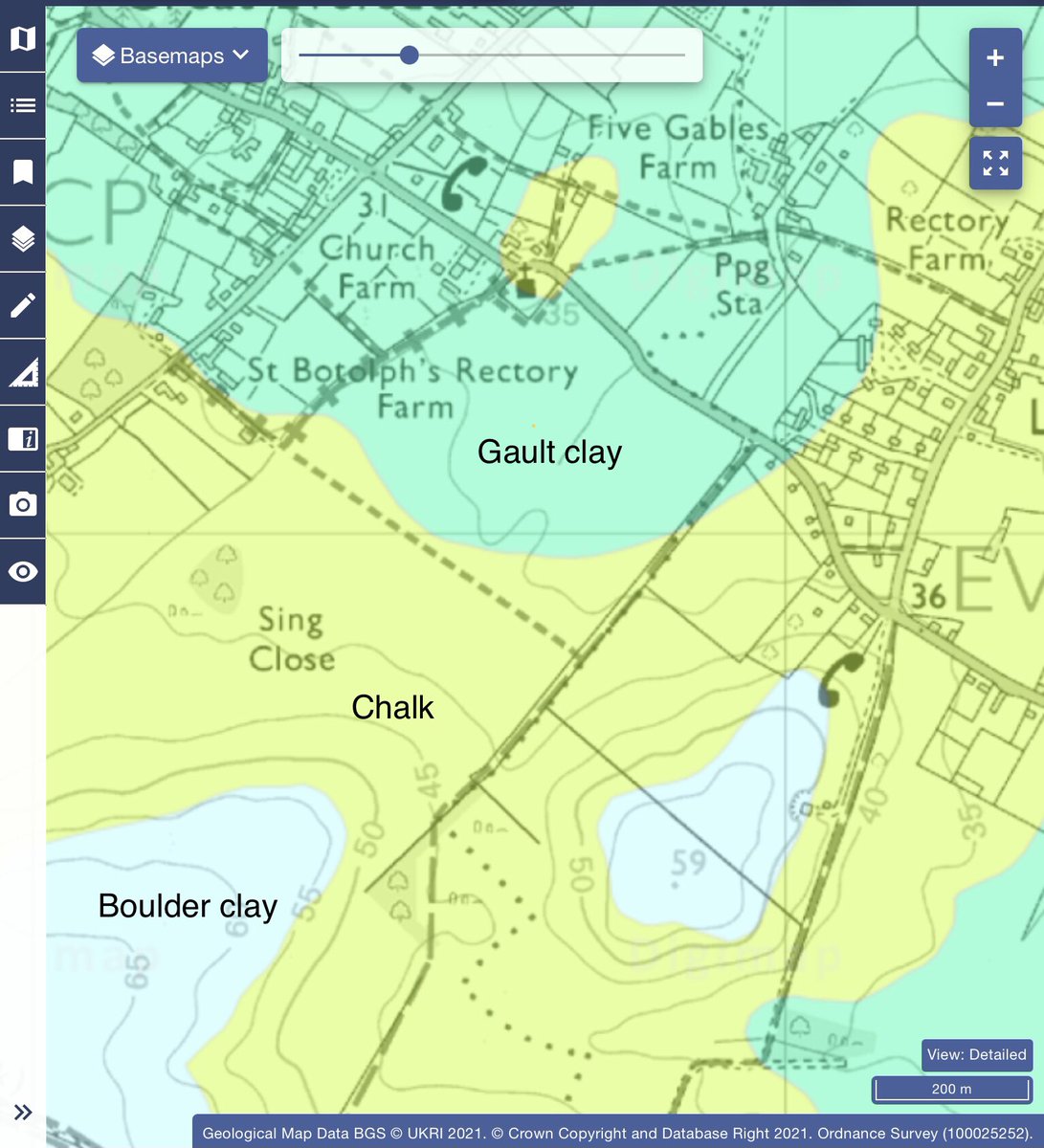

5. Here in S Cambs. it depends in a combination of the lie of the land and its geology. The hill slope at the base (S) of the map, where the contour lines are close together, gives way to a much flatter landscape to the N. That’s enough to begin to slow the flow of water ..

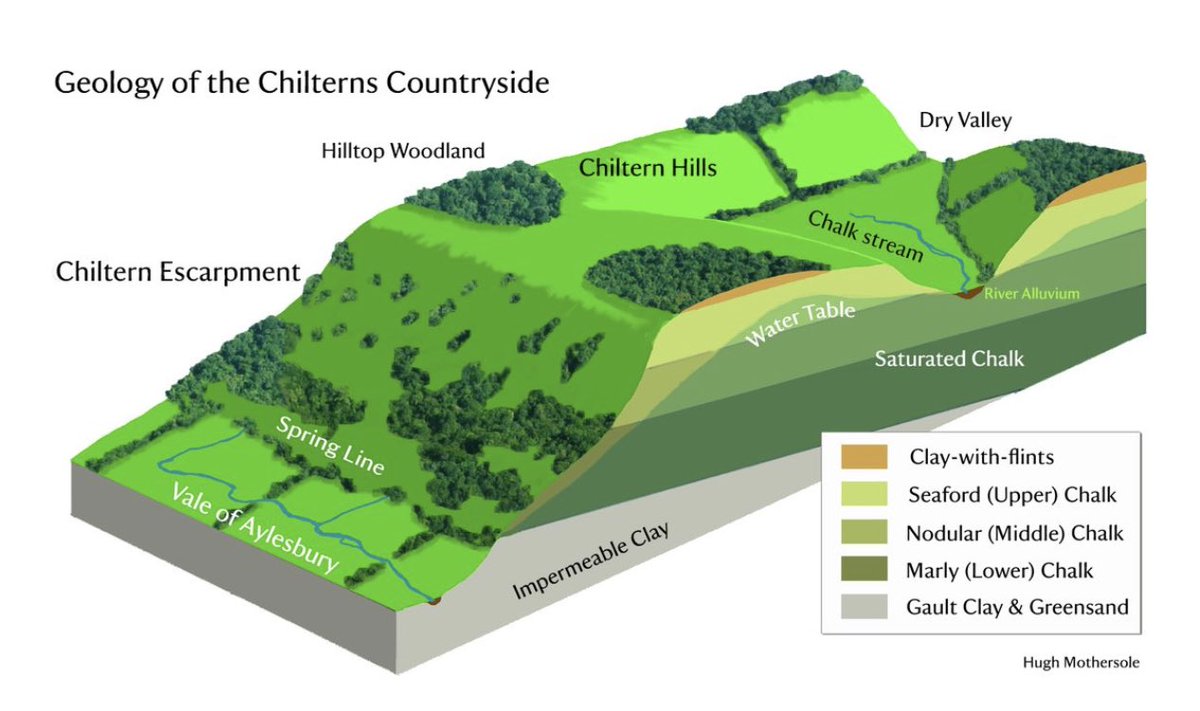

6. .. towards the river a mile or 2 to the N. But geology plays as important a part. Rain falls evenly across the landscape. Some runs down the hill from Boulder clay to chalk to gault clay, but much permeates downwards through the clay & then the chalk. But

7. ..the gault clay is already saturated - it can’t take any more water. So where the water flowing through the chalk meets the gault it’s forced out in springs (image https://astonrowant.wordpress.com/droving-in-the-chilterns/drovers-3-high-ground/) and then flows across the surface of the land. But that’s not straightforward.

8. because it has to cross what Christopher Taylor calls ‘hummocky ground’: ground that traps the water as it’s uneven. Partly because, as in this field, it’s full of anthills, an indication that it hasn’t been ploughed for centuries, and partly because

9. the surface was (before ploughing) interrupted by ponds, small and large, each surrounded by a low bank. They are called pingos. Like this one still surviving in Norfolk, they are remnants in the landscape of the ice age. (Photo https://freshwaterhabitats.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Stow-Bedon-Common-Survey-Report-2016.pdf)

10. Briefly: in the last Ice Age as the water was forced out between chalk & gault, the springs froze creating larger and smaller lenses of ice. Over time a thin layer of soil began to cover them. When the ice eventually melted an embarked pond was left behind. Maybe

11. some of these flooded areas are the remains of pingos in the modern, now more often ploughed, landscape?

12. Waterlogged, hummocky, this was land that was very difficult to plough before the modern era. Some carries faint traces of medieval ridge & furrow, like that outlined by buttercups here - the same field across which my boots were squelching.

13. Such traces were created by tenants so desperate for land/food around 1300 that they put all the extra difficult effort into ploughing the gault, risking losing their crops to floods. When the population fell c1350 these fields were abandoned & once more reverted to pasture.

14. Sometimes that hummocky ground has been manicured into village greens as at Barrington. Taylor reminds us that villages were often settled on the worst land so as to maximise the area of land available for arable. You can also see that in the geology map in this thread.

15. The land overlying the gault had always been used as pasture as far back as one might wish to go. It was an extensive area, exploited under rights of common defensible in law, the focus of a small early medieval polity .. https://twitter.com/drsueoosthuizen/status/1188013045924159488

16. So every time I see water flowing across the fields, down the lanes, I think of the springs, the gault, the hummocky ground & the generations of households whose livelihoods depended in large part on the cattle & sheep that grazed their extensive common pastures. END

More via …https://profsusanoosthuizen.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/oosthuizen-2008-bar.pdf, and …https://profsusanoosthuizen.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/oosthuizen-2002-landscape-history-2002-24-1-73-88.pdf.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter