Kicking off #enigma2021 second day with our Contact Notification panel, moderated by @benadida with panelists Mike Judd, CDC COVID-19 Exposure Notification Initiative; Ali Lange, Google; Tiffany C. Li, Boston University School of Law; Marcel Salathé, EPFL

https://www.usenix.org/conference/enigma2021/presentation/panel-contact-tracing

https://www.usenix.org/conference/enigma2021/presentation/panel-contact-tracing

Ben: The reason why we cannot be here in the same physical space is the same reason we have this panel on Contact Tracing. What is that?

* Run around looking for people who have been infected

* And looking for people who have been exposed to the people who have been infected

* Run around looking for people who have been infected

* And looking for people who have been exposed to the people who have been infected

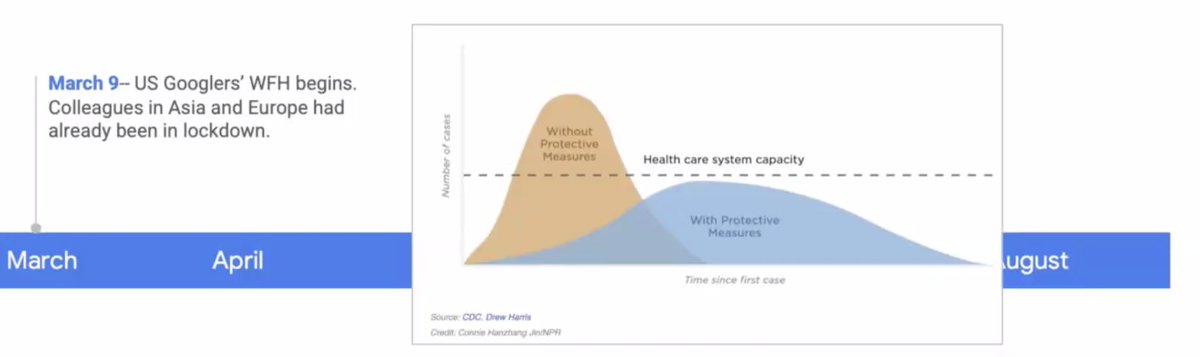

* To try to contain the spread

2020 is when COVID-19 emerged. And people asked "can we apply technology?" can we use our cell phones, which know about location and can contact servers to record who we're close to in case someone is, unfortunately, positive for COVID-19

* should we?

* do we need it?

* will public health know how to use it?

* will they want to?

* will people game it?

* will the location data be misused?

* do we need it?

* will public health know how to use it?

* will they want to?

* will people game it?

* will the location data be misused?

Marcel: runs the digital epidemiology lab at EPFL

Want to talk about development and launch of .ch contract tracing app

"An Ode to Pragmatism"

Want to talk about development and launch of .ch contract tracing app

"An Ode to Pragmatism"

Did one of the first papers on digital contact tracing a decade ago, this represents a long line of work.

See http://sociopatterns.org website for examples

See http://sociopatterns.org website for examples

In the wake of SARS-cov-2 and COVID-19 became very important to aid manual contract tracing with technology. Challenge is that people can be infectious before they're symptomatic, so cannot just focus on isolating people with symptoms -- they have already infected others

So need very rapid contact tracing for this particular bug

That's a better model than non-targeted quarantine (aka lockdown), which is no fun

That's a better model than non-targeted quarantine (aka lockdown), which is no fun

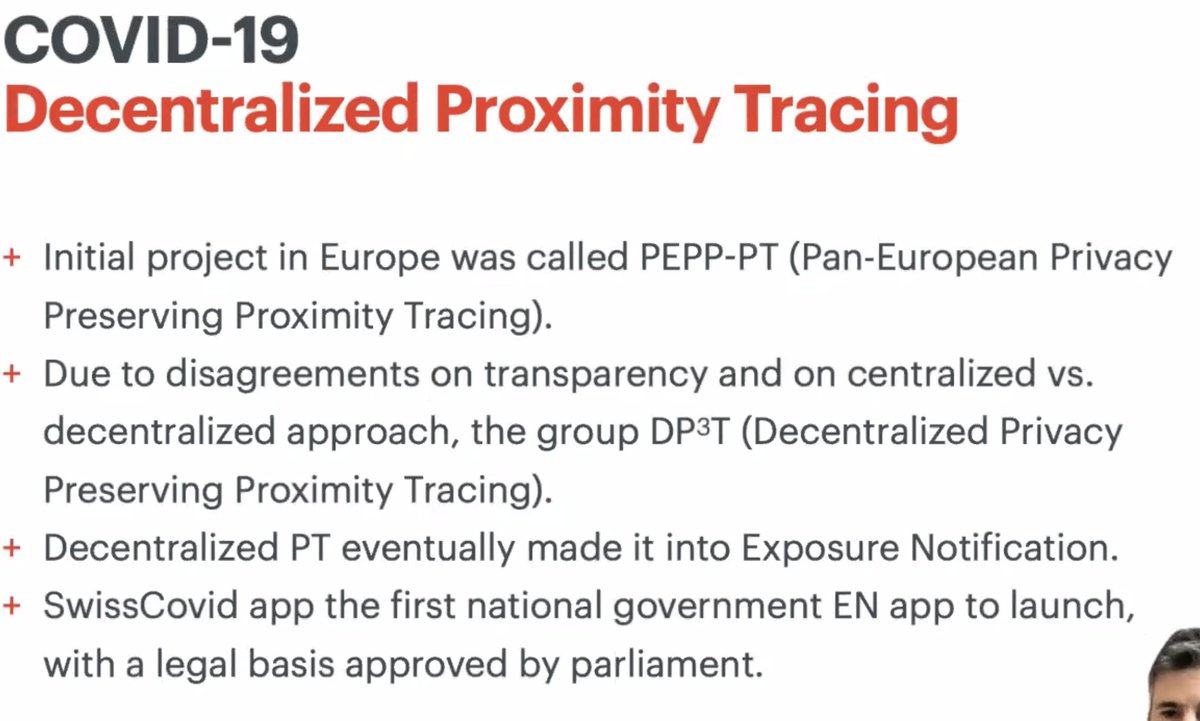

Started initial project in Europe PEPP-PT, but some people wanted to build something completely transparent and decentralised (DP3T) -- made it into the Apple/Google covid app, and was the first national government EN app to launch

Digital proximity tracing is a classical case of needing both tech and relevant domain expertise. At EPFL we'd already been building those bridges -- you can't build them [well] during the crisis.

This is a harder problem than most appreciate!

This is a harder problem than most appreciate!

The academic system has a really hard time with this (especially when it comes to incentives):

* few journals

* few grants

* few prizes

* work reviewed by single-domain experts

All of these things are important in the academic infrastructure.

[ YES! ]

* few journals

* few grants

* few prizes

* work reviewed by single-domain experts

All of these things are important in the academic infrastructure.

[ YES! ]

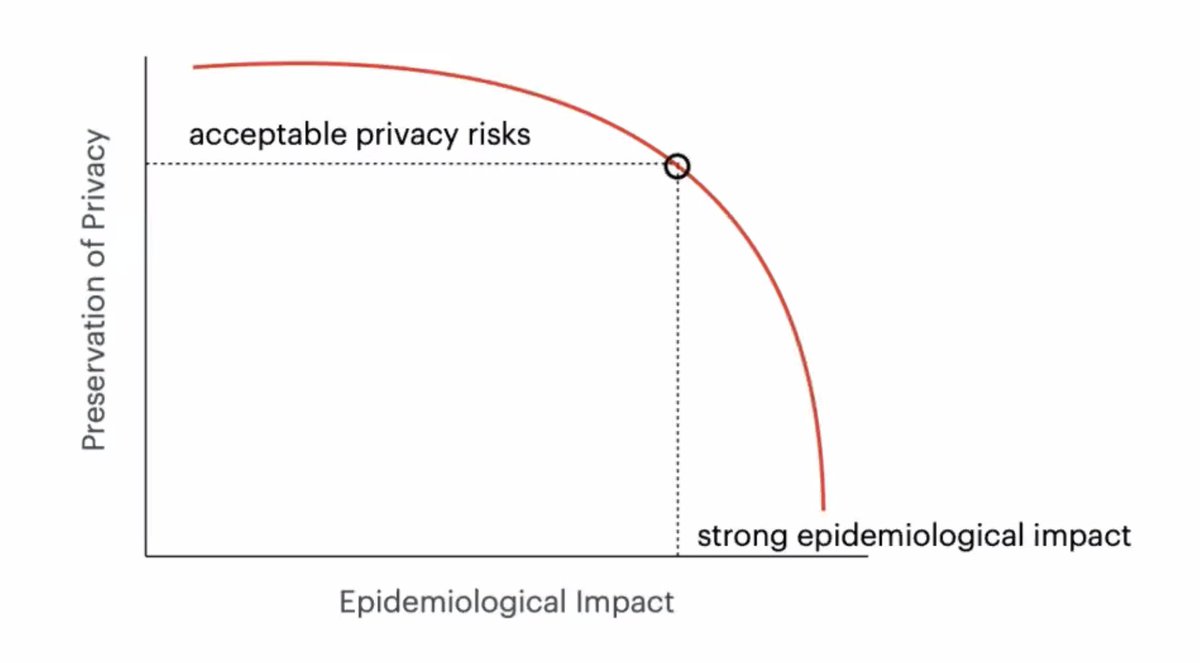

Widespread myth in epidemiology: we need more data to solve the data. Strong belief that privacy preservation means you can't solve the problem (and vice versa).

More data can help, but you first should ask how you can solve the problem without collecting data.

More data can help, but you first should ask how you can solve the problem without collecting data.

Try to harness technology to the maximum extent possible to bend this curve. The exposure notification framework ended up being this.

This is great, but these ideas were attacked heavily be people looking through lens. "This is not the *best* solution from a privacy perspective" or "this is not the *best* solution from an epidemiological perspective" without understanding the very real issues.

So:

* build the bridges early

* sidestep the fights from people with narrower lenses

* build the bridges early

* sidestep the fights from people with narrower lenses

@AletheaLange:

I'm not going to explain the crypto. That's already well-explained online. ;)

Note: literally 100s of people worked on the things I'm going to talk about and this is just my story. I'm also going to be mostly talking about the US, which isn't the full picture

I'm not going to explain the crypto. That's already well-explained online. ;)

Note: literally 100s of people worked on the things I'm going to talk about and this is just my story. I'm also going to be mostly talking about the US, which isn't the full picture

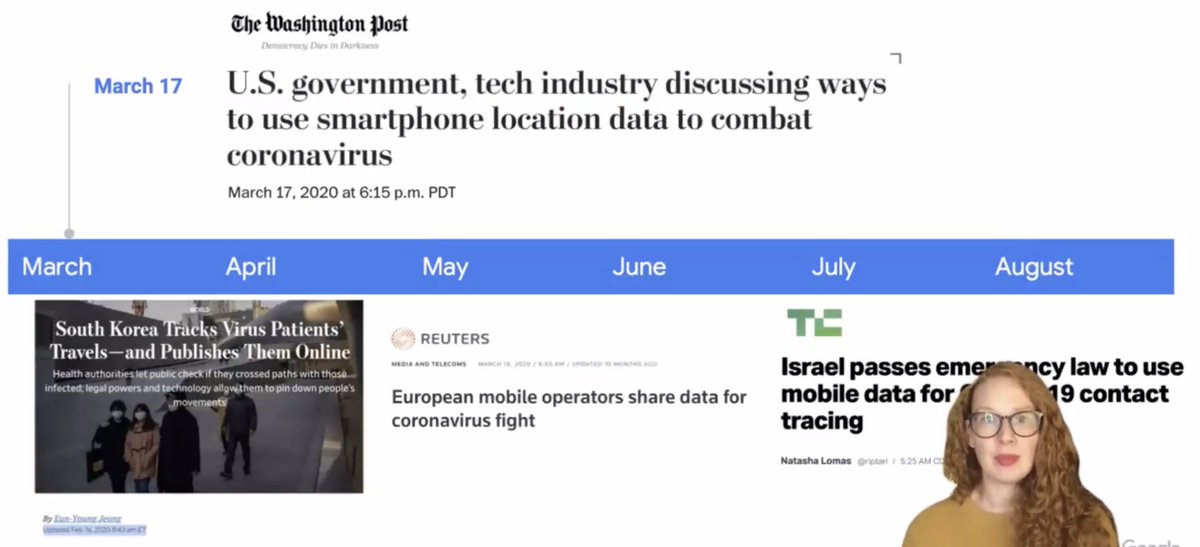

Google put out a statement about what were thinking -- our instincts were to look at aggregate patterns of movement.

The community mobility reports (still up online) help governments and people see how their communities are responding to lockdowns. Have heavy privacy protection.

The community mobility reports (still up online) help governments and people see how their communities are responding to lockdowns. Have heavy privacy protection.

Started talking about contact tracing and conversation shifted to Bluetooth low energy (BLE) rather than location data [it's not fine-grained enough and doesn't work well in buildings]

But there were issues with Apple/Google compatibility, battery issues, issues where the app had to be in the foreground. So Apple/Google partners to solve this problem.

... announced before the tech was built [no one likes that!] and people worked incredibly hard to compress months of work into weeks.

Also renamed "contact tracing" to "exposure notification" to help people understand we were helping contact tracing, not replacing it.

Also renamed "contact tracing" to "exposure notification" to help people understand we were helping contact tracing, not replacing it.

Also made people use API so could protect privacy.

We considered privacy protections key -- if people didn't trust it, they wouldn't use it, wouldn't carry their phones

We considered privacy protections key -- if people didn't trust it, they wouldn't use it, wouldn't carry their phones

Once the Exposure Notification tech launched, governments started launching apps using it.

Also improved the BLE tech, spent a ton of time explaining how it worked and putting out explainer docs.

Also improved the BLE tech, spent a ton of time explaining how it worked and putting out explainer docs.

Growing understanding that it was really hard for governments to build the apps. So we launched "exposure notification express", which is basically building blocks to building an app.

Things we learned

* names matter

* governments need more support

* proactive communications on privacy protections and phone settings

* transparency is essential (open source)

* be humble

* don't give up

* names matter

* governments need more support

* proactive communications on privacy protections and phone settings

* transparency is essential (open source)

* be humble

* don't give up

Tiffany:

As a privacy researcher, when I first started looking at the contact tracing apps, all I saw were the privacy problems (I use it! I urge people in specific states to use it -- why specific states? I'll explain later)

As a privacy researcher, when I first started looking at the contact tracing apps, all I saw were the privacy problems (I use it! I urge people in specific states to use it -- why specific states? I'll explain later)

Other speakers have talked about the specific exposure notification tech, like the Apple/Google protocol which is the most privacy-protective.

* used to supplement, not replace contact tracing (people calling to ask who you've had contact with)

* used to supplement, not replace contact tracing (people calling to ask who you've had contact with)

The tech folks may have gotten a little too excited. They're promising, but they haven't been implemented at the scale needed

There are risks: who is collecting the data and who has access to the data?

There are risks: who is collecting the data and who has access to the data?

We haven't seen as much adoption of even the privacy-preserving apps because people don't trust the governments or these companies

If we think these apps are important, then we need to solve the core trust issue. One way to use privacy-preserving protocols

If we think these apps are important, then we need to solve the core trust issue. One way to use privacy-preserving protocols

This is important because there are many risks to this data being collected, no matter how secure your app or company is, especially sensitive types of heath data.

Have to think about misuse of data by authorized actors like governments. e.g. Singapore admitted their contact tracing app data could be used for other purposes including law enforcement.

This hurts use of the app and can harm civil liberties if governments can access and possibly misuse data for unlimited purposes.

There are also equity concerns. Privacy protections might be enough to get some people to adopt, but privacy harms might be worse for certain marginalized communities

[ I'd say this needs a per-protection-scheme discussion and leaves out the trust issues which are broader]

[ I'd say this needs a per-protection-scheme discussion and leaves out the trust issues which are broader]

How about HIPAA? Only covers "covered entities" like clinics and health care providers. Not application developers.

Google and Apple may not be able to crack down on every app.

Google and Apple may not be able to crack down on every app.

Also if there's a hack, have to send out a breach notification (much worse if it's centralized, not the privacy-preserving Apple/Google approach)

Consumer protection laws can be used to protect people using apps developed be people who aren't public authorities. Enforced by the FTC. Doesn't do enough.

Greatest privacy problem is shifting norms about how we think about health privacy.

The privacy-preserving approach is great! But not all states are using this and users don't necessarily know which one is going on. Users are getting more used to have their data collected

The privacy-preserving approach is great! But not all states are using this and users don't necessarily know which one is going on. Users are getting more used to have their data collected

Laws have some protection, but we need more legal protections.

Health privacy can be more critical than other kinds of privacy. You can't change your health information, like you can change your password. It's unique to you and important.

Health privacy can be more critical than other kinds of privacy. You can't change your health information, like you can change your password. It's unique to you and important.

We need to think about how to protect privacy moving forward and how to shift the norms of privacy back.

Mike:

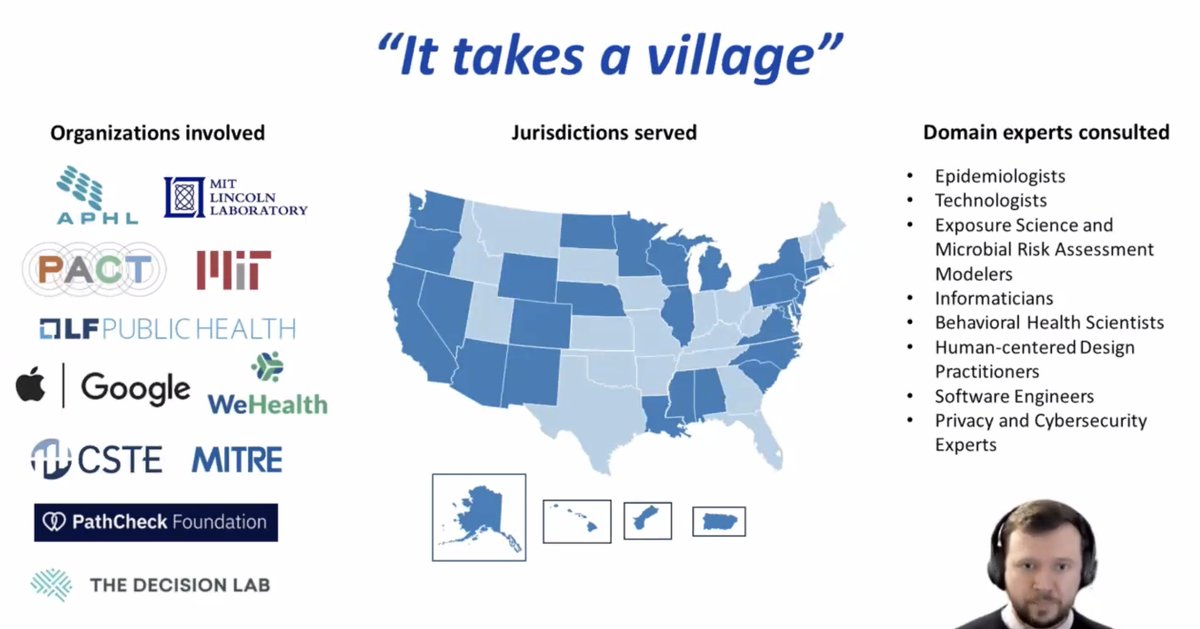

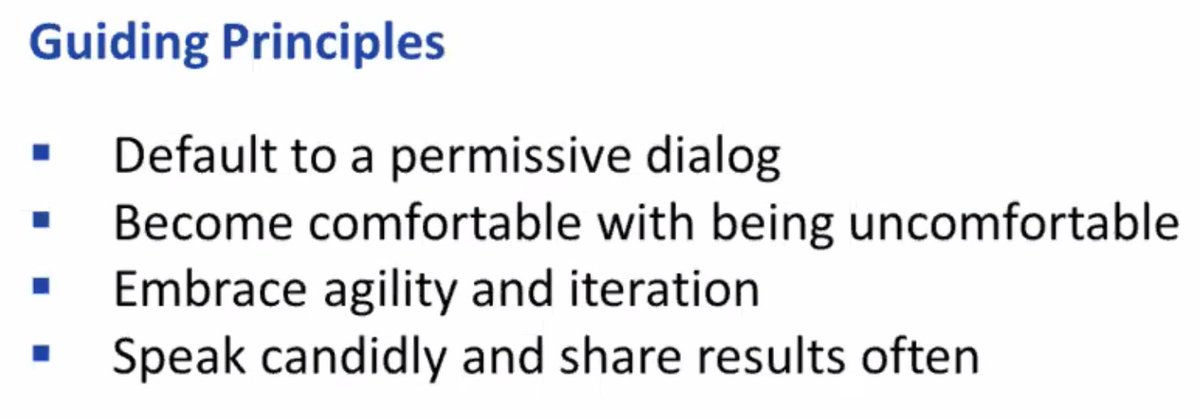

Want to explore interdisciplinary problem-solving and how this has led to some successes in deployment of Apple/Google exposure notification system

Want to explore interdisciplinary problem-solving and how this has led to some successes in deployment of Apple/Google exposure notification system

1. promoting inclusive environment helps get things done. It takes a village. Parochialism can prevent collaboration and can't get things done -- need tech people and public health people (and more)

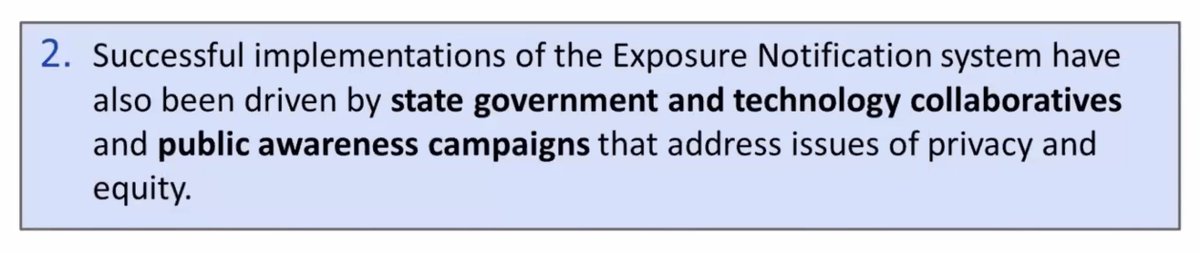

2. successful exposure notification launches have been driven by state government and technology collaborations

State highlights:

* AZ: adding more messages about up-to-date transmission information

* CO: automation of part of the process of verification

* NJ: use of open source code

* WA: marketing including lead singer of Pearl Jam, translation to 36 different languages

* AZ: adding more messages about up-to-date transmission information

* CO: automation of part of the process of verification

* NJ: use of open source code

* WA: marketing including lead singer of Pearl Jam, translation to 36 different languages

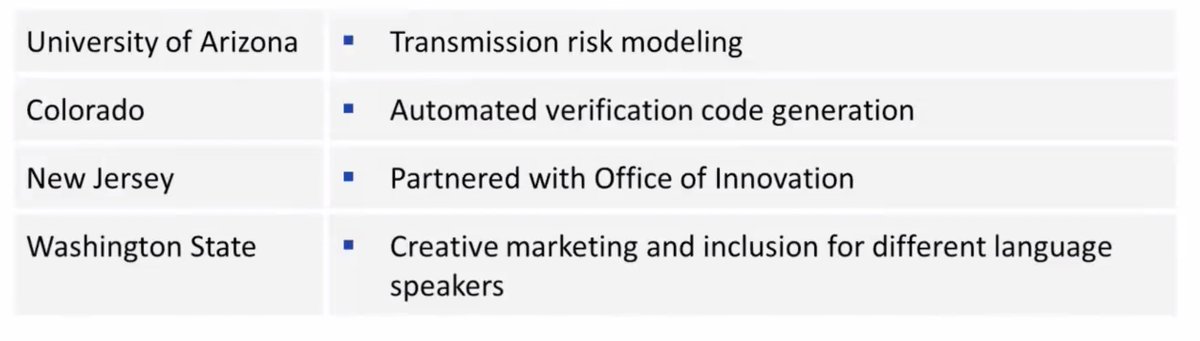

analytics portal will allow more rigorous evaluation

[side note: there are privacy protections on this]

[side note: there are privacy protections on this]

Next steps:

* what's next for these relationships after the pandemic?

* how do we generalize these lessons and apply them to persistent problems in public health?

* what's next for these relationships after the pandemic?

* how do we generalize these lessons and apply them to persistent problems in public health?

[ done with intro and time for questions. I'm going to have to only type some of these to save my hands ]

Ben: thank you so much for taking the time to do this panel! You're all so busy and we deeply appreciate this

Ben: thank you so much for taking the time to do this panel! You're all so busy and we deeply appreciate this

Q: did things like randomized BT/wifi addresses impact the feasibility?

A: Marcel: I'll pass on the technical details, but questions like these came up all the time. How far are you going to go in preservation on privacy and what is the impact from an epidemiological perspective

A: Marcel: I'll pass on the technical details, but questions like these came up all the time. How far are you going to go in preservation on privacy and what is the impact from an epidemiological perspective

If you tweak the protocol you could possibly answer some interesting epidemiological question but you would compromise the privacy. We took the position that we wouldn't try to solve too many problems at once.

Epi wanted to tackle problems that you normally can't tackle at all

Epi wanted to tackle problems that you normally can't tackle at all

Pained me to say this but said let's aid the manual contact tracers, maximum privacy. Once it's taken up we can talk about other points on the tradeoff curve.

Ali: the sentiment was that privacy was not an extra thing we were adding on -- critical to success. Tradeoff is not "same # of participants, more data" -- if you don't make the same promises, you will have fewer participants.

Mike: It worked out how Google/Apple put together this temporary exposure key approach (it's a rotating identifier to foil people sniffing for keys). Rotates once per day. Corresponds to CDC's understanding of exposure to be cumulative across the date. Good to see convergence

Q: Is this working? Is there a difference between countries with low- and high-spread?

A:

Ali: Couple of studies. One from Oxford/Google. Looked at modeling what effectiveness would be at levels of adoption. Saw predicted effectiveness at even low levels of adoption

A:

Ali: Couple of studies. One from Oxford/Google. Looked at modeling what effectiveness would be at levels of adoption. Saw predicted effectiveness at even low levels of adoption

There are some stats on downloads from public health authorities

Real-world study in Spain. 30% adoption, able to detect ~6 contacts per infected individual, which was 2x manual contact tracing. This is doing a good job of supplementing manual contact tracing.

Real-world study in Spain. 30% adoption, able to detect ~6 contacts per infected individual, which was 2x manual contact tracing. This is doing a good job of supplementing manual contact tracing.

Mike: Can think about effectiveness in intermediate outcome or ultimate outcome

want to encourage public health behaviours (masking, quarantine). That's really hard to do in an app -- we can't confirm personal health behaviour.

want to encourage public health behaviours (masking, quarantine). That's really hard to do in an app -- we can't confirm personal health behaviour.

Can do better at intermediate outcomes, e.g. time to contact tracing notification.

Can also increase comprehensiveness of notification

Can also increase comprehensiveness of notification

Marcel: When you ask how well does EN work, that's a difficult question also because the tech is embedded in a public health process where a lot of things can go wrong

for example in a lot of countries including Switzerland you need a code -- and if it doesn't get delivered...

for example in a lot of countries including Switzerland you need a code -- and if it doesn't get delivered...

Q Ben: we have the hard part and the "easy" parts like delivering the code (which clearly isn't easy). What sounds easy to tech people but was actually hard?

A:

Marcel: Many things! People from one field doesn't understand challenges *or* solutions from the other field. Example: blog post from Bruce Schnier saying "digital contact tracing is dumb" and as an epidemiologist this is ... dumb

Marcel: Many things! People from one field doesn't understand challenges *or* solutions from the other field. Example: blog post from Bruce Schnier saying "digital contact tracing is dumb" and as an epidemiologist this is ... dumb

We've been thinking about this for 30 years. It's hard not just to say "this person doesn't get it" when it gets picked up in the media. We can have a debate but when you're in the middle of building something and have a public conversation at this low level...

Have to establish communities way before.

[ suspect Marcel would like Bruce and others not to go off half-cocked as well, but is too polite to say ]

[ suspect Marcel would like Bruce and others not to go off half-cocked as well, but is too polite to say ]

Tiffany:

People were surprised at how few people wanted to download the app even when they know it works. When it comes down to it, most people don't know what these apps are.

People were surprised at how few people wanted to download the app even when they know it works. When it comes down to it, most people don't know what these apps are.

Most people don't know what these apps do, where data is going. All they know is a scary government or company is putting out an app and don't want to download it. We should have worked harder on... but that was pretty difficult last year especially in the US because ... gov't

Need to not only make the tech safer -- need to make it clear to people that the tech is safer. People know they care about privacy, but don't know how to protect themselves. Need to make this usable for people.

Q Ben: Love the point you made about shifting norms and public trust. Most of us carry cell phones. Lots of tradeoffs with that, and now there's this huge possible benefit with EN can can do it without privacy downsides... but how can people understand which are the "good" apps?

A:

Tiffany: Black Mirror joke: "what if phones but too much"

EN can be "what if phones but too little"

What if there was a federal app [US]? Would that help? There should at least be interoperability. Right now some are done in the best privacy-preserving manner. Some are *not*.

Tiffany: Black Mirror joke: "what if phones but too much"

EN can be "what if phones but too little"

What if there was a federal app [US]? Would that help? There should at least be interoperability. Right now some are done in the best privacy-preserving manner. Some are *not*.

For individual consumer it's really hard to know the difference. Could there be a national standard or framework... outside the ones which are already published.

Users also really don't have a choice, they have to use the one where they are

Users also really don't have a choice, they have to use the one where they are

Q Ben: how do you build trust with the public in a pandemic?

A:

Mike: it requires consistent messaging. Support from local trusted figures (e.g. Pearl Jam, Starbucks in WA)

A:

Mike: it requires consistent messaging. Support from local trusted figures (e.g. Pearl Jam, Starbucks in WA)

Making it easier -- a few clicks from the homescreen really helps. Giving the option right there and making it easy really helps.

Q: Why in the US did we make every state make their own app to use the same Google/Apple framework?

A:

Mike: Authority and responsibilities not given to the federal government is given to the states. That's what's spawned the more federated approach. CDC's role is to support.

A:

Mike: Authority and responsibilities not given to the federal government is given to the states. That's what's spawned the more federated approach. CDC's role is to support.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![The academic system has a really hard time with this (especially when it comes to incentives):* few journals* few grants* few prizes* work reviewed by single-domain expertsAll of these things are important in the academic infrastructure.[ YES! ] The academic system has a really hard time with this (especially when it comes to incentives):* few journals* few grants* few prizes* work reviewed by single-domain expertsAll of these things are important in the academic infrastructure.[ YES! ]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EtOwQqhVcAUGuGk.jpg)

![Started talking about contact tracing and conversation shifted to Bluetooth low energy (BLE) rather than location data [it's not fine-grained enough and doesn't work well in buildings] Started talking about contact tracing and conversation shifted to Bluetooth low energy (BLE) rather than location data [it's not fine-grained enough and doesn't work well in buildings]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EtOyTfOU0AEunY1.jpg)

![analytics portal will allow more rigorous evaluation[side note: there are privacy protections on this] analytics portal will allow more rigorous evaluation[side note: there are privacy protections on this]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EtO4ycCUcAI4Fdc.jpg)