This is a thread about a plane crash in 1941 that occurred not on a foreign battlefield or a remote training base, but in a suburban street in the Blue Mountains, just west of Sydney.

Around 4.45pm on 28 January 1941, residents in the Blue Mountains town of Glenbrook heard the sound of a RAAF Avro Anson flying overhead. Those who looked for the noise saw the aircraft emerge from overcast clouds.

What happened next would stay with witnesses for a lifetime. The silver Anson’s port wing appeared to ‘shatter’, leaving a trail of debris as the aircraft began to roll. One resident claimed to have even heard the wing ‘crack’.

Witnesses recalled the aircraft’s engines increased in noise and the nose briefly lift, but as more pieces came away – now from the starboard wing as well – the crew and occupants were largely consigned to their fate.

In its final moments, RAAF Anson A4-5 rolled to port before hitting a light post at the corner of Clifton Avenue and Lucasville Road in Glenbrook, sending a cloud of flame and black smoke.

The events leading to the crash took less than 10 seconds to unfold. Within 10min of the crash, a crowd of Glenbrook residents had gathered around the wreck, though it was clear they could offer little assistance.

From a yard on Clifton Ave, 12yo Pam Thompson had watched the entire chain of events whilst playing with her friends that Tuesday afternoon. She recalled her mother closed the gate and told them “that’s no place for children to be”.

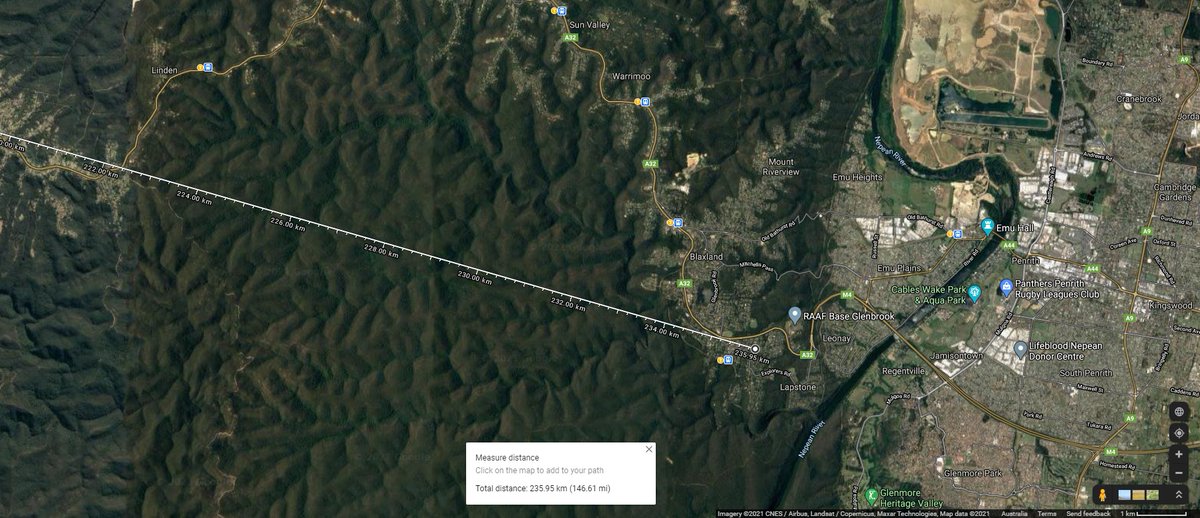

The town of Glenbrook sits on the terrace of the Blue Mountains, and on a clear day offers a view all the way to Sydney. It would take police some time to travel from nearby Springwood and Penrith to arrive at the site.

RAAF personnel from Richmond would be an hour away, and set a guard to block access to Clifton Avenue at both ends. There were only a handful of houses on the surrounding streets, and they were remarkably unscathed.

The RAAF would later retrieve the wreck and remains of the five men on board Anson A4-5, and residents – including 11yo Tim Miers – would assist RAAF investigators with finding pieces of the Anson that had fallen during the crash.

All five men on board were from RAAF Station Parkes, where the RAAF had established its Air Navigation School the previous year. All five had joined the RAAF in the 12 months leading to the accident.

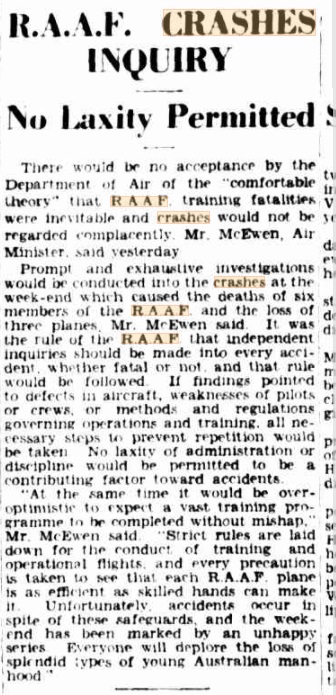

January 1941 was not a good month for RAAF air safety. In the month before January 28, it had suffered no less than 10 aircraft accidents for the loss of 9 lives; before January 28, there were mounting calls for an enquiry into RAAF air safety.

The Minister of Air largely dismissed calls for an enquiry largely on account of these accidents result of pilot error, but bear in mind – the RAAF was undergoing a massive increase in workforce.

From a pre-war workforce of 3500, the RAAF by March 1940 received 68,000 applications to join, approx. 10,000 of which for aircrew. In 1940, it would begin training its contribution to the Empire Air Training Scheme.

Many of those who joined in 1940 were put back into the training pipeline as instructors so that they RAAF could generate aircrew required to support the War in Europe. The growth was repeated everywhere - in technical trades, engineering & sustainment, and fleet management.

A training system producing hundreds of aircrew each month – supported by a technical workforce and airbase infrastructure similarly undergoing massive growth – was bound to produce an environment where accidents were paid for in blood.

In the case of Anson A4-5, the reason for its crash was judged to be a structural failure of its wing, however the reasons for why that wing separated bear closer consideration.

Also, please bear in mind that I have no training aviation safety and I am not a historian.

Also, please bear in mind that I have no training aviation safety and I am not a historian.

Let’s look at the Avro Anson. It was introduced to RAAF service from 1937, and although often referred to as a ‘bomber’ at the time, it was – truth be told – a light twin-engine observation aircraft.

A4-5 is pictured here leading a formation.

A4-5 is pictured here leading a formation.

As you can see, the aircraft was equipped with a turret for a Vickers machine gun and could carrying a few hundred pounds of bombs, but its value to the RAAF would be two-fold.

Firstly, its intended purpose with the RAAF was coastal reconnaissance. The RAAF in 1935 was directed to help secure sealanes. Given the choice of buying a larger number of cheaper landplanes or fewer expensive flying boats, it chose the former option - and went with the Anson.

Secondly, it would allow the RAAF to develop experience with a more 'advanced' aircraft. The Anson was our first monoplane; it was one of our first multi-engine aircraft; and it had an enclosed cockpit and retractable landing gear.

These features don't make the Anson 'advanced' in itself, but it would prove an essential stepping stone for the RAAF in progressing from biplanes of the 20s and early 30s towards the aircraft it would operate in the 40s.

Part of this would see the Anson train and build experience for a generation of pilots, navigators, wireless operators and other aircrew before they progressed to larger and more advanced aircraft.

48 Ansons were introduced to RAAF service over 1937-1938. A handful were lost in accidents during the pre-war years and 1940, but their value to the RAAF – and Commonwealth - was becoming apparent.

With the outbreak of War in September 1939, the RAAF's Ansons were quickly conducting coastal patrols and soon would be assigned to schools training personnel under the Empire Air Training Scheme.

Hundreds more Ansons would be shipped to Australia from England to be assigned to these schools, and aircraft were often passed around. A4-5 was no different.

In 1940, A4-5 was transferred from the General Reconnaissance School at Point Cook to the Air Observers school in Cootamundra, before coming to RAAF Station Parkes to serve with 1 Air Navigation School.

On 28 January 1941, Squadron Leader James Rainbow – the senior medical officer for RAAF Station Parkes – requested the use of an Anson to transport a patient to Sydney for urgent medical care - the alternative of rail transport being deemed unsuitable.

Pilot Officer Bailey Middlebrook Sawyer, a navigation instructor, had suffered an ear infection the previous week. Born in Washington DC, he was an experienced oceanographer and had served with as a merchant marine

Married to an Australian, Sawyer was in Melbourne on his 100ft schooner-yacht ‘Henrietta’ when war broke out. Whilst serving in the RAAF in 1940, he ran his yacht aground at Point Cook. I can't find the story behind that one.

Rainbow, born in London in 1899, was a doctor in Sydney before the war and initially worked on recruitment trains in 1940 before being posted to Parkes. His request to air transport Sawyer was approved.

Around 3pm, Rainbow and Sawyer climbed into the Anson. Their crew was Pilot Officer John Newman as the pilot; Flying Officer Henry Skillman as the navigator; and Aircraft Charles Tysoe as the wireless operator

Pilot Officer Newman over 300 flying hours, of which over 200 were on Ansons. A talented Rugby Union player from Toowoomba before the War, had been assessed as an ‘average’ or ‘average plus’ pilot during his pilot training.

A4-5 was not rigged for dual controls, and Flying Officer Skillman (navigator) sat next to the Newman at the front. Sawyer (patient) sat on the navigator seat; Rainbow next to him; Tysoe at the wireless station.

Taking off from Parkes into clear weather at 3.35pm, Newman had been told to fly at low level to alleviate the pressure on Sawyer’s ear. Passing Orange and Bathurst, the aircraft encountered low cloud on reaching the Blue Mountains.

At 4.32pm, Tysoe reported the aircraft’s position 12 nautical miles south of Lithgow, giving no indication of any problems with the aircraft. At 4.38pm, the last transmission was made to switch radio frequency to Sydney.

Glenbrook residents recalled two layers of cloud over the Blue Mountains that afternoon; it’s speculated Newman flew between layers, remaining clear of terrain but hoping for a gap that would allow him to fly lower.

It’s fair to assume that with Skillman as navigator, Newman was approximately aware he was near Glenbrook and the Sydney basin before he commenced the descent. Never-the-less, Glenbrook is still 300ft above the Sydney basin.

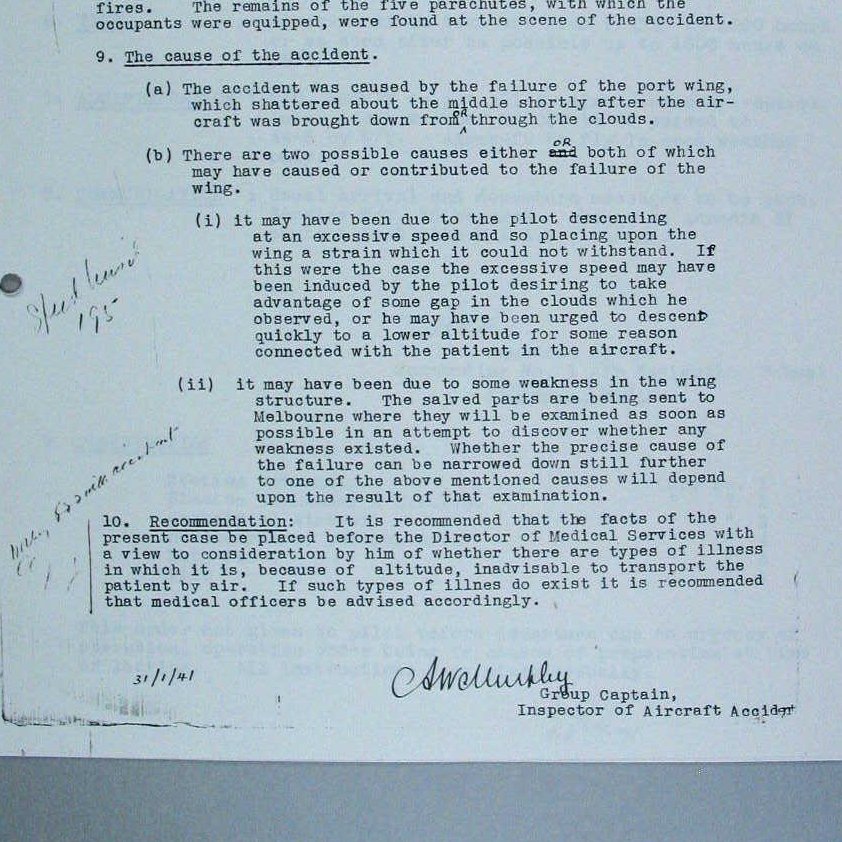

The crash investigation determined the Anson crashed after wing separation during descent from cloud. What’s not clear is whether separation occurred due to existing damage to the wing, an overspeed, or both.

Being a product of the 1930s, the Anson's wing was primarily constructed from plywood and spruce; I would assume even a small failure of the wing structure (or even the surface) could have lead to a catastrophic failure.

As an aside - there's a good look at an Anson restoration at https://acesflyinghigh.wordpress.com/2019/01/19/restoring-an-avro-anson-2019-update/, which gives some impression of the Anson's structure.

During the investigation, the RAAF (aided by Glenbrook residents) recovered a trail of debris approximately 600m long before the crash site. The conclusion they made was the port wing separated first, followed by pieces of the starboard wing.

My assumption is that following separation of the port wing, the stress on the starboard wing led to pieces to come away as well. With the Anson in a dive, and no clear ground surrounding them, there was little Newman could do to recover.

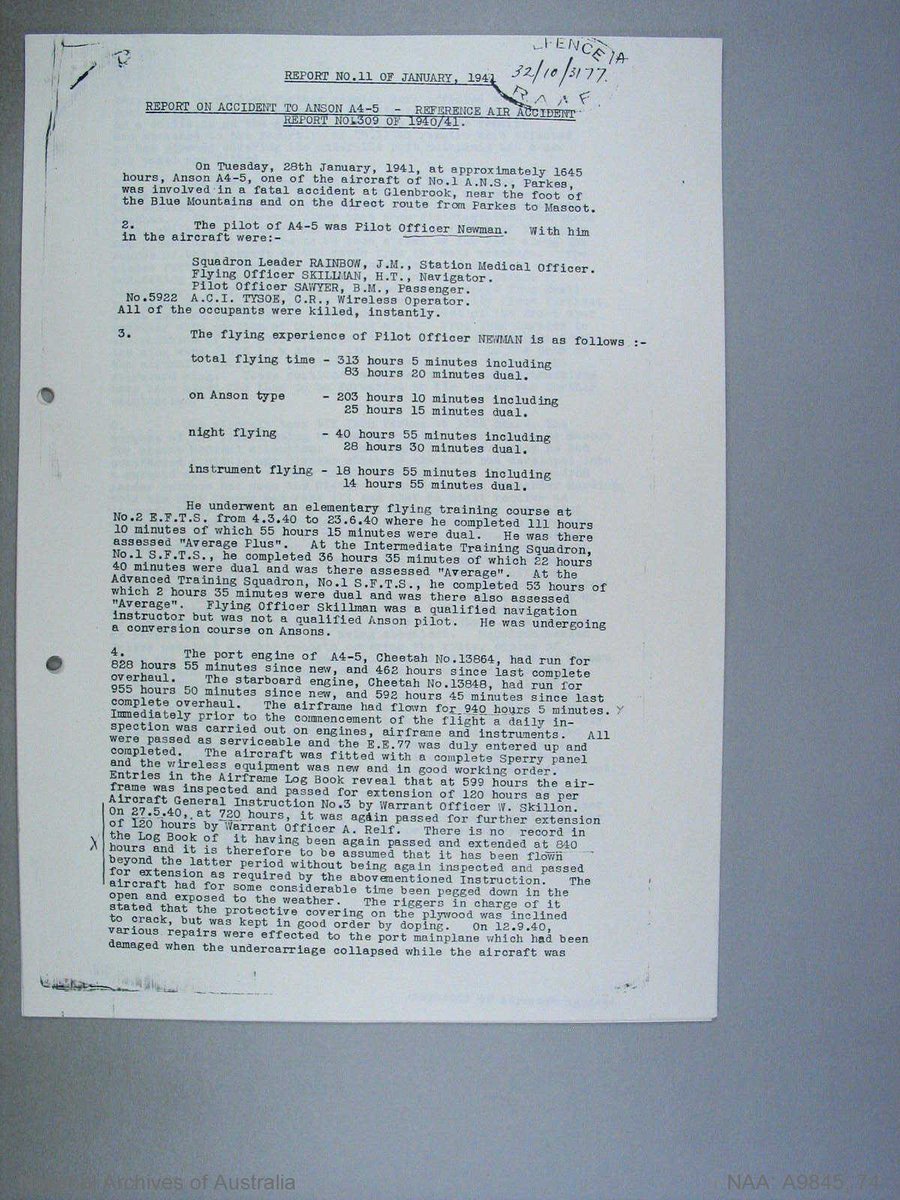

Why did A4-5’s port wing separate at all? The initial - and incorrect - assessment by investigators is that it overflew its inspection by 100 hours.

This assessment that A4-5 missed a major inspection was rejected by engineers, because the aircraft underwent an out-of-cycle inspection. What follows is a convoluted example of RAAF maintenance in the early war years.

In the 12 months prior to A4-5’s crash, the airframe underwent several changes of hands and accidents which might have contributed to its demise.

In 1940, A4-5 was passed from the General Reconnaissance School at Point Cook to the Air Observers School at Cootamundra to the Air Navigation School at Parkes.

It had undergone a routine inspection at Point Cook at 720 flying hours logged; after another 56 flying hours (and shortly after arrival at Cootamundra), it suffered a landing gear collapse in June 1940 that damaged its port wing.

Repairing the wing at Cootamundra, the Warrant Officer Engineer took the opportunity to conduct the regular 120-hour inspection out-of-cycle.

Separate to this and around this time, the RAAF extended Anson scheduled inspections from 120-hour intervals to 180-hour intervals.

Separate to this and around this time, the RAAF extended Anson scheduled inspections from 120-hour intervals to 180-hour intervals.

By my count, A4-5 had approximately 776 hours logged at this time.

In September 1940, A4-5's port wing came for another knock, struct by a taxiing DH84. More repairs were conducted.

In September 1940, A4-5's port wing came for another knock, struct by a taxiing DH84. More repairs were conducted.

In November, parts of its port wing were resurfaced. In Parkes, A4-5 was kept outside; riggers treated plywood cracking with doping.

Here's a summary of the work conducted to A4-5 in the months prior to its crash.

Here's a summary of the work conducted to A4-5 in the months prior to its crash.

According to the summary provided by technical staff following the crash, A4-5 wasn’t due for scheduled 180-hour inspection until 947 flying hours (956 by my count).

It crashed at 940 flying hours logged on the airframe.

It crashed at 940 flying hours logged on the airframe.

Would A4-5 have crashed if it had have received a scheduled 120-hour inspection at ~896 flying hours? Who can say. The question of why the RAAF moved to an extended cycle begs consideration however.

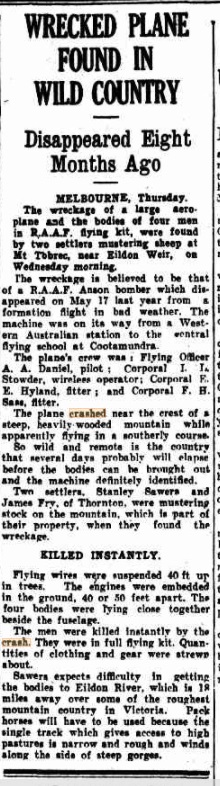

In an odd coincidence, shortly before A4-5’s crash, the wreck of Anson A4-4 was discovered bear Melbourne. It had been missing in May 1940 during a flight to Camden, approx. 15km south of Glenbrook. http://www.adf-serials.com.au/AvroAnsonA4-4CrashMtTorbreck.pdf

Had A4-5 crashed just minutes before it did in Glenbrook, it’s reasonable to assume its wreck too would have been obscured within the Blue Mountains.

The accident investigation for A4-5 recommended future aeromedical evacuations be considered as to whether the patient needed to be transported at low altitude, and speculated Sawyer's condition spurred Newman to dive to a lower altitutde.

In the aftermath of A4-5’s loss, the men on board were buried or cremated. Skillman and Sawyer left widows. Sawyer’s remains were scattered over his yacht at Point Cook.

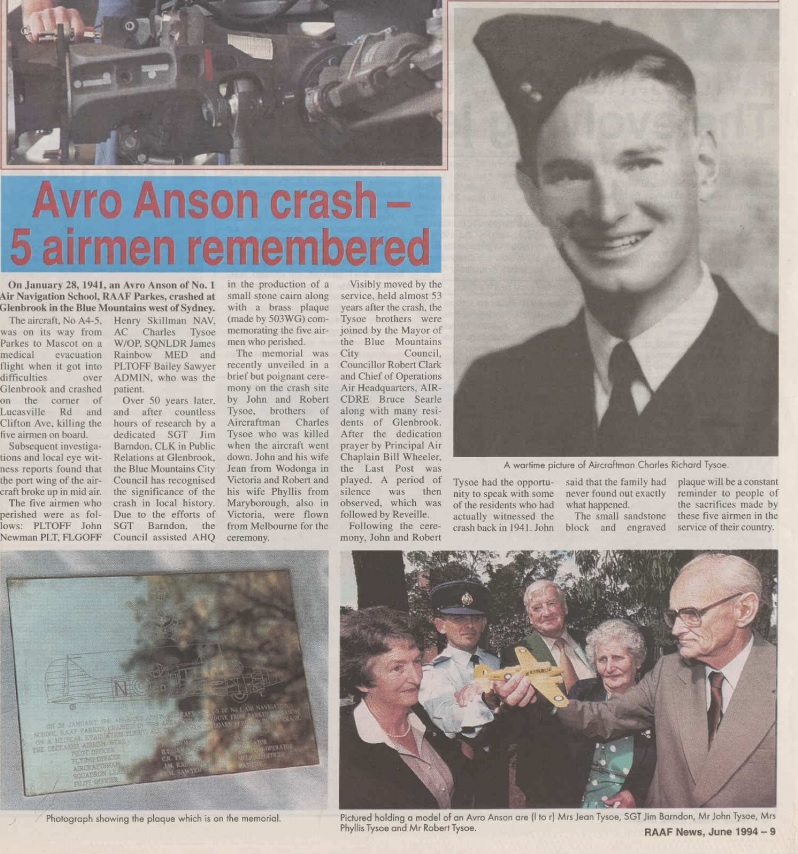

Newman’s loss was deeply felt in Toowoomba, and likewise Tysoe’s loss was similarly felt in Geelong.

For many, Anson A4-5's loss faded as another sad loss amongst the hundreds killed in accidents during the War. Clifton Avenue and Lucasville Road developed into leafy suburban streets, and coincidentally, a RAAF Base was established at the nearby Lapstone Hotel in February 1950.

The story of how Anson A4-5 came to be memorialised brings us to 1992, when a request from an ex-RAAF member E Collas (living in nearby Emu Plains) wrote to RAAF Base Glenbrook’s PR Office

The idea was brought to Blue Mountains City Council, which approved and contributed to a small memorial at the crash site with the RAAF. A plaque was made by RAAF 503 Wing and it was installed 24 Mar 1994.

Over the coming years, the memorial would often be lost or overlooked in its site. Many RAAF personnel who walked through Glenbrook had little idea it existed. The Glenbrook & District Historical Society pushed to have a bronze plaque mounted on 25 Apr 19.

The Historical Society then sourced a large sandstone memorial onto which the plaque was mounted in December 2019

To mark the accident's 80th anniversary, the memorial was re-dedicated in a joint service between the RAAF, Blue Mountains City Council, and Glenbrook & District Historical Society.

Pam Thompson (3rd from right), who witnessed the crash as a 12yo, spoke at the ceremony. Also present was Tim Miers (right, in red), who saw the crash as an 11yo and helped recover the debris.

The re-dedication of the memorial formed part of RAAF Base Glenbrook's Centenary of Air Force activities in 2021, reinforcing the base's links to the community. Sadly, that link was first established with the loss of five men on a Tuesday afternoon, 80 years before.

These connections within the community exist around us, whether or not we realise it; and have connections to faraway communities and families. Every day driving to/from work, I pass the site of at least two major aircraft accidents in the last 77 years.

In choosing photos from the re-dedication service in Glenbrook last week, we deliberately selected this one. While it might be judged for having too much negative space, the brown soil on the roadside almost appears like a scar that hasn't quite healed, eight decades on.

If you've made it this far through the thread, I'm grateful for any corrections you can provide. Special thanks to National Archives Australia, Trove, ADF-Serials, AWM, the OzAtWar website, and Glenbrook & District Historical Society - latter of whom have kept this memory.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter