THREAD on why

1. Primary school transmission depends crucially on child prevalence, not just community prevalence, and

2. Why we see delays for primary school transmission to ramp up, if child prevalence starts low. 1/

1. Primary school transmission depends crucially on child prevalence, not just community prevalence, and

2. Why we see delays for primary school transmission to ramp up, if child prevalence starts low. 1/

Imagine an ideal world where people with noticeably covid-like symptoms can afford to immediately isolate (a disastrously poor assumption in many places, but I’ll return to it briefly in tweet 6). 2/

Adult X transmits to coworker Y.

2 days later, X develops symptoms and isolates. On day 4, X gets a test. On day 5, it comes back positive. On day 6, X contacts coworker Y.

In this ideal world, Y immediately isolates, but by then he's already infected someone on the subway. 3/

2 days later, X develops symptoms and isolates. On day 4, X gets a test. On day 5, it comes back positive. On day 6, X contacts coworker Y.

In this ideal world, Y immediately isolates, but by then he's already infected someone on the subway. 3/

Next, consider 14-year-old teenager T. She doesn’t have a paid job, but she’s unlucky and gets infected while queuing at a shop, on an errand for family.

5 days later, she develops symptoms after school, but by then she has already infected a friend at school that morning. 4/

5 days later, she develops symptoms after school, but by then she has already infected a friend at school that morning. 4/

But now consider a young child.

Parent P transmits to his 8-year-old, C.

2 days later, P develops symptoms and the whole family isolates. C attended school for those two days, but 2 days was way too short for C to become contagious,

so C infected no one. 4/

Parent P transmits to his 8-year-old, C.

2 days later, P develops symptoms and the whole family isolates. C attended school for those two days, but 2 days was way too short for C to become contagious,

so C infected no one. 4/

For young children, the main sources of infection are households and other children.

If child prevalence is LOW, then most child infection comes from home,

and USUALLY, an infected parent will develop symptoms early enough for the child to isolate before infecting anyone. 5/

If child prevalence is LOW, then most child infection comes from home,

and USUALLY, an infected parent will develop symptoms early enough for the child to isolate before infecting anyone. 5/

So in a situation of low child prevalence, usually an infected young child can only transmit at school if

a) their infected parent never developed symptoms,

b) their infected parent couldn’t afford to isolate, or

c) the child had an unusually short incubation period. 6/

a) their infected parent never developed symptoms,

b) their infected parent couldn’t afford to isolate, or

c) the child had an unusually short incubation period. 6/

When you combine these constraints with the fact that the majority of young child infection is coming only from households in such a context, this adds up to very slow initial increases in child prevalence.

Like this: 7/

Like this: 7/

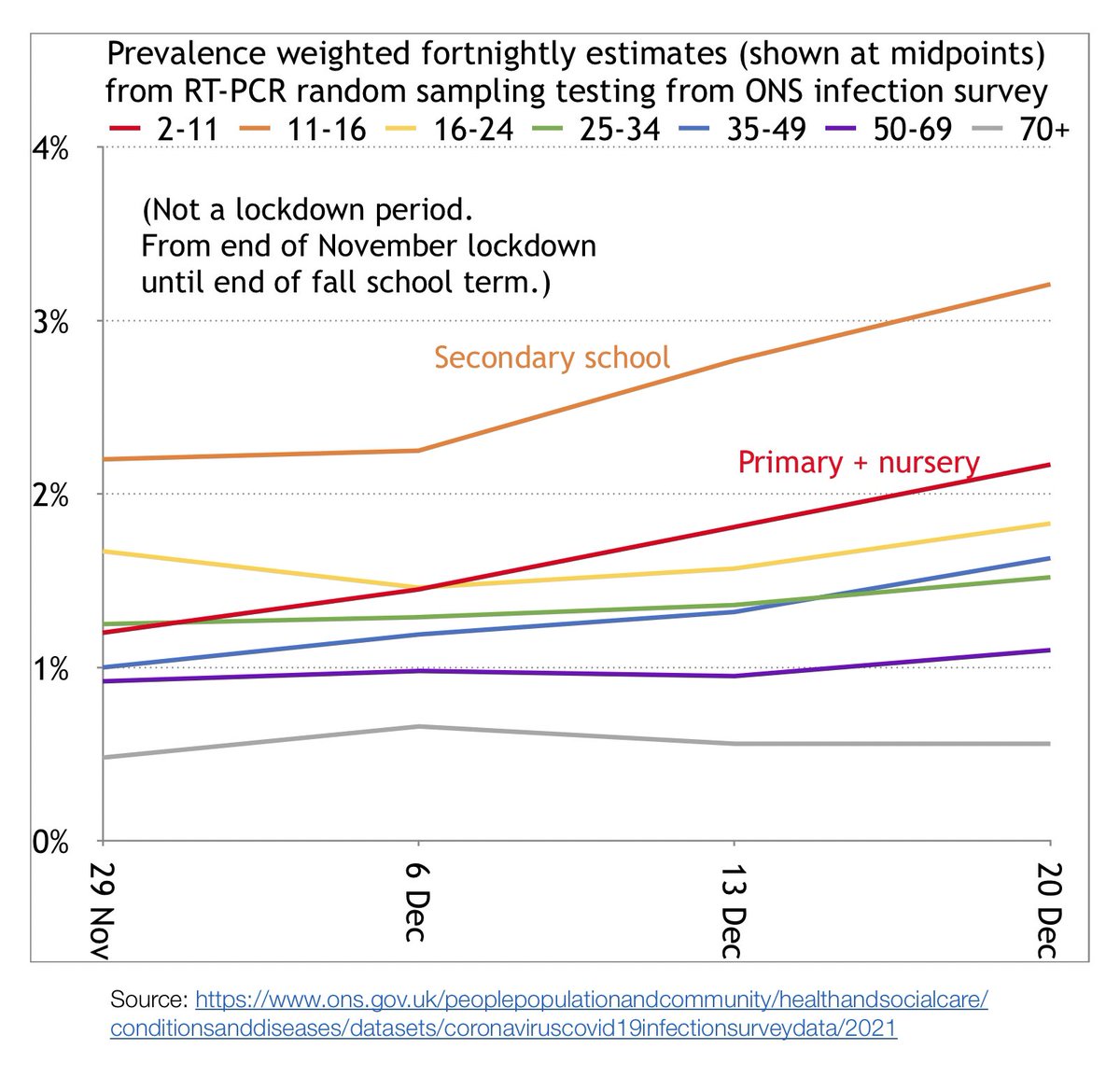

However, once child prevalence surpasses a certain critical threshold, a phase transition of sorts occurs.

Suddenly, the majority of child infection isn’t coming from homes; it’s from pauci-/pre-/a-symptomatic kids at school,

and we see relative increase trends like this: 8/

Suddenly, the majority of child infection isn’t coming from homes; it’s from pauci-/pre-/a-symptomatic kids at school,

and we see relative increase trends like this: 8/

When we locked down in November but left schools fully open, that no longer left us with a low-child-prevalence cushion.

So when lockdown lifted, primary school student infection had faster growth than any adult age group did, both from an absolute and a relative standpoint. 9/

So when lockdown lifted, primary school student infection had faster growth than any adult age group did, both from an absolute and a relative standpoint. 9/

What happened next?

From 27 Dec-3 Jan (with schools closed) 2-11s and 11-16s were the only 2 age groups to drop in prevalence, while all other age groups increased.

Note: this might be confounded by spread of the B.1.1.7 variant from children to adults during this period. 10/

From 27 Dec-3 Jan (with schools closed) 2-11s and 11-16s were the only 2 age groups to drop in prevalence, while all other age groups increased.

Note: this might be confounded by spread of the B.1.1.7 variant from children to adults during this period. 10/

On 6 Jan, primary schools opened fully for one day, followed by 21% of primary students in-person, with nurseries at 54% usual (13 Jan DfE values, high regional variance).

From 10 to 17 Jan, 2-11s and their parent age group were the only 2 groups to increase, 2-11s faster. 11/

From 10 to 17 Jan, 2-11s and their parent age group were the only 2 groups to increase, 2-11s faster. 11/

(Secondary schools had much lower attendance upon reopening—just 5%.)

Warning: the above data from January should be interpreted with caution, since ONS WFE prevalence is only one source of data, and some effect sizes were small, relative to certainty of measurement. 12/

Warning: the above data from January should be interpreted with caution, since ONS WFE prevalence is only one source of data, and some effect sizes were small, relative to certainty of measurement. 12/

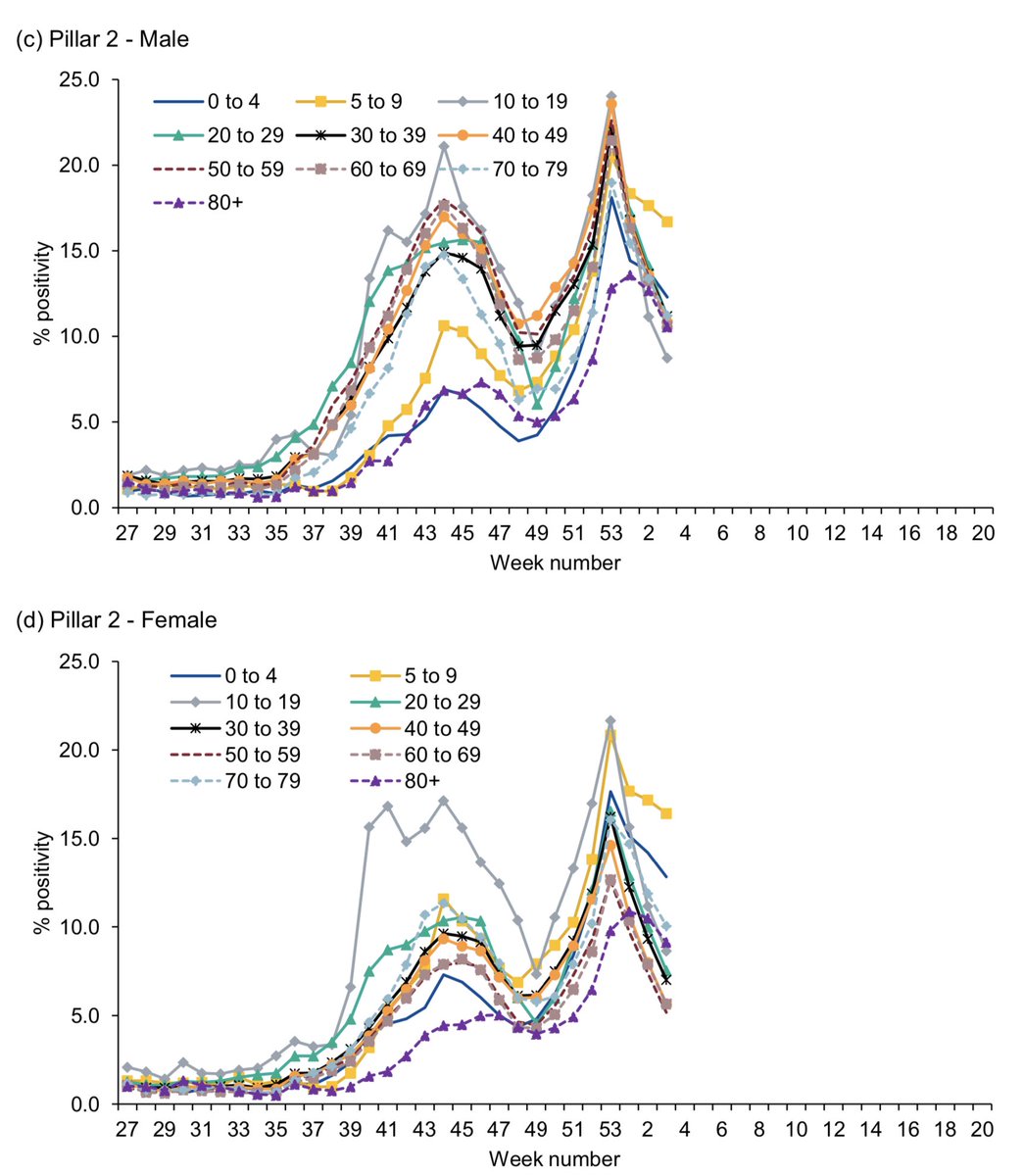

Also, some sources of data from January and late December are slightly conflicting.

For instance, Pillar 1 shows somewhat differing trends in positivity from those of Pillar 2. These data are much more impacted by targeting and test methodology.

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/956709/Weekly_Flu_and_COVID-19_report_w4_FINAL.PDF. 13/

For instance, Pillar 1 shows somewhat differing trends in positivity from those of Pillar 2. These data are much more impacted by targeting and test methodology.

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/956709/Weekly_Flu_and_COVID-19_report_w4_FINAL.PDF. 13/

But I’ve kind of meandered off topic here.

The real point of this thread was to emphasise that the dynamics of primary school transmission depend crucially on whether a critical threshold for child prevalence has been reached. 14/

The real point of this thread was to emphasise that the dynamics of primary school transmission depend crucially on whether a critical threshold for child prevalence has been reached. 14/

The transmission dynamics for an index child at school who acquired their infection from adults at home

should differ, on average, to those for an index child who acquired infection from non-household children.

The latter occurs more often when child prevalence is high. 15/

should differ, on average, to those for an index child who acquired infection from non-household children.

The latter occurs more often when child prevalence is high. 15/

It’s also an oversimplification to say that school transmission just depends on community prevalence.

Even with high community prevalence, if young child prevalence starts out low, primary school transmission will be low... for a time. 16/

Even with high community prevalence, if young child prevalence starts out low, primary school transmission will be low... for a time. 16/

Conversely, if you lockdown enough to lower community prevalence on average, but child prevalence remains high, then in some circumstances that can springboard back into rapid rises in prevalence as soon as lockdown is lifted.

Still, that depends on many other factors. 17/

Still, that depends on many other factors. 17/

In any case, asking questions about how primary school transmission functions without specifying what the underlying child prevalence is

is a bit like describing the behaviour of water without mentioning whether you’re discussing ice or steam. 18/

is a bit like describing the behaviour of water without mentioning whether you’re discussing ice or steam. 18/

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter