So today let's have a short lesson in survey methodology and how it can lead us astray.

Lots of people would like to know how Iranians actually feel about their government, and what the true religious mix in Iran is.

But this is hard to do, because the government strongly opposes survey research into these topics, and people may fear giving honest answers.

But this is hard to do, because the government strongly opposes survey research into these topics, and people may fear giving honest answers.

The logical conclusion then is to develop a secure platform that people trust the regime won't breach, and to use it to host a survey.

But if you do that, you have a new problem.

What if the sample you recruit is biased? The more secure you make your system, the weirder your respondents may be.

What if the sample you recruit is biased? The more secure you make your system, the weirder your respondents may be.

This is a hard issue to deal with! Conventionally, you deal with this kind of issue by "weighting," figuring our systematic differences between your sample and the population of interest and counting some respondents more/less.

So if your sample got you 25% people ages 20-29, but the true population is 23%, you'll count your 20-29 year olds a bit less each than others.

This approach is great for adjusting for normal sampling error.

However, it really does not work if your sampling error is not random. You have to actually re-weight based on whatever variable you're selecting against: what is the variable driving odds of being surveyed?

However, it really does not work if your sampling error is not random. You have to actually re-weight based on whatever variable you're selecting against: what is the variable driving odds of being surveyed?

This is a famously hard problem. Any given survey has a plausibly infinite number of such selection variables. Virtually no survey is ever actually a perfectly random sample of the population. Incomplete sampling frames and biases in respondent response rates always exist.

But in some cases, this is easy to control for or at least conceptualize. If I survey people at my church, I *know* that answers to the question, "Are you a Lutheran?" are not representative of the wider U.S. population.

I know that I can't make any inference. No amount of weighting will fix this problem, but I can at least understand the limits of my survey.

Enter the problem of sampling in authoritarian states:

If people know the survey is not regime-approved, or that surveys generally are not regime-approved, respondents will tend to be regime-skeptical people.

If people know the survey is not regime-approved, or that surveys generally are not regime-approved, respondents will tend to be regime-skeptical people.

Oddly enough, surveys done in authoritarian places can oscillate wildly between obsequious pro-regime attitudes towards wild-eyed anti-regime attitudes, just based on respondent beliefs about instrument security and orientation towards the regime.

There's a second problem:

Modern surveys down in authoritarian countries often try to leverage secure, remote, online platforms to guarantee privacy. But the people who are online on social media in mid- and low-income authoritarian states may not be representative!

Modern surveys down in authoritarian countries often try to leverage secure, remote, online platforms to guarantee privacy. But the people who are online on social media in mid- and low-income authoritarian states may not be representative!

Again, *within* classic re-weighting groups, like age, education, sex, etc, the group who is online and chooses to respond to a survey may be unusual in hard-to-predict ways, especially if the internet and social media is a key channel for various cultural or political ideas.

In Iran's case, we know that the regime sees social media as a threat to regime stability, and that it has often been used to organize resistance to the regime. Within Iran, there's a strong perception that the internet is an unfriendly place for the regime.

So, when we have an online survey provided in a secure way in an authoritarian context where social media has been a vehicle for anti-regime organizing in recent memory, that sample may not be representative!

But again, if the sample is large enough, and if the bias in selection is *stochastic* and not *deterministic*, i.e. if at least *some* of all the populations of interest are being sampled, with sufficiently creative weighting, we COULD control for this.

One way to control would be to explicitly control for ideology. Basically just re-weight respondents based on support for the regime.

But to do that, you need to know the true distribution of ideology in the society.

But to do that, you need to know the true distribution of ideology in the society.

In Iran's case, you can use election results, in theory. Re-weight based on voting odds.

This works if you think your sample is basically similar to the electorate. But again, this is not an easy thing to test, especially since retrospective recall of voting can be poor.

This works if you think your sample is basically similar to the electorate. But again, this is not an easy thing to test, especially since retrospective recall of voting can be poor.

And if your sample is *hugely* different along this axis, you may worry that weighting isn't enough: a huge disproportion would tend to suggest that your bias is non-random, which suggests you may also have non-random selection *within groups*.

That is, even controlling for who a person voted for, they may be ideologically different from their broader coalition. Pro-regime voters who nonetheless are on social media and will participate in a poll may nonetheless be unusual and different.

So, last year a huge (n=50,000) online survey was taken of Iranian beliefs and opinions by a group of Iranian exiles who set up a special platform to administer this survey. https://gamaan.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/GAMAAN-Iran-Religion-Survey-2020-English.pdf

Their method was basically to set up the link and then do a huge social media promotion on various prominent influencers' pages, and trust participation to snowball from there as people shared the survey with friends.

So right here we can see the problem shaping up.

Snowball sampling is a great method if you want to rack up a huge number of respondents *but don't really care much about how representative they are.*

Snowball sampling is a great method if you want to rack up a huge number of respondents *but don't really care much about how representative they are.*

Say you want to understand the experiences of women in Hasidic communities. Snowball sampling is great for this. You contact a half dozen people, survey them, then say, "Hey, pass me along to your friends who I can't plausibly directly reach myself." And so on.

So if what you want is to get a big, noisy sample of a specific social network, snowball sampling is a good (and relatively "cheap") method.

But it is not a good method for a putatively representative survey.

But it is not a good method for a putatively representative survey.

Why?

Because the social network approach will overwhelmingly bias towards the network of the researchers themselves and likeminded people.

Because the social network approach will overwhelmingly bias towards the network of the researchers themselves and likeminded people.

Of their 50,000 respondents, fully 10,000 had to be dropped on the basis of not being in Iran or inconsistent responses.

The remaining 40,000 they say are representative of literate adults in Iran. Crucially, "literate adults" in Iran is only 85% of adults in Iran. So they are claiming their sample is representative of 85% of adults, who are probably the most-educated, most-Westernized 85%.

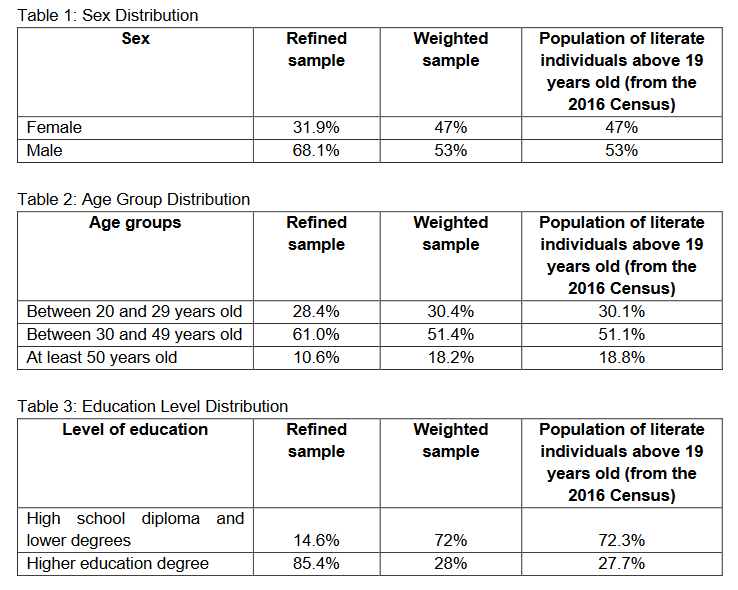

But when we look at their unweighted sample, there's a problem. Compare the refined sample to the census results (1st and 3rd columns).

Their sex split is.... pretty noisy, but workable. Age looks fine.

HOLY COW EDUCATION.

85% of their sample was college-educated vs. 28% of their target population.

HOLY COW EDUCATION.

85% of their sample was college-educated vs. 28% of their target population.

And geographically, they had 4% rural vs. a true 21% rural mix, and they had ***40%*** Tehran vs. 19% in reality.

So they MASSIVELY oversampled educated, urban people.

So they MASSIVELY oversampled educated, urban people.

They reweight for this. But y'all, weighting works fine when you're nudging; when your respondents are getting weights running from like 0.3 to 3.

But with how huge their weight factors are, they've gotta have respondents with weights at like 15 or 20.

But with how huge their weight factors are, they've gotta have respondents with weights at like 15 or 20.

And again, the issue here is that when we see this kind of huge sampling issue, the assumption we have to make is that this is ***not random***. Some non-random factor drove these patterns. The odds of randomly drawing this sample from the underlying population is insanely low.

So re-weighting isn't enough, because we can be pretty confident that what's going on here is a selection bias that probably impacts within-group selection.

They also include a weight variable for presidential vote. Here's how it looks. Again, look at those huge gaps.

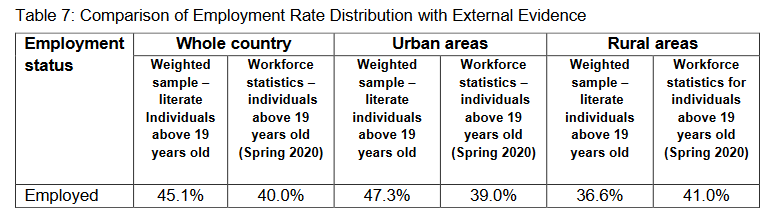

Now, they do an external validity test. They use their data to estimate unemployment rates and compare to the official unemployment rate. They say this shows that their 95% credibility interval is validated by these results. I say it's falsified by these results.

In their *one test*, they did not in fact get within 5% of their target variable for the whole population or either subsample.

It is definitionally less than 5% odds that drawing a >5% error sample would occur, so this tells us they've miscalculated their true error.

It is definitionally less than 5% odds that drawing a >5% error sample would occur, so this tells us they've miscalculated their true error.

The reason they've miscalculated is basically their model assumed random noise as the kind of variation in a lot of places where in fact the noise was not random, but highly selective on important unobserved (or even observed but uncontrolled) attributes.

They are claiming that 40% of literate Iranians are non-religious, that 8% are Zoroastrians, and that a mere 32% are Shia Muslims.

Y'all, we've got non-totalitarian Muslim countries with reliable survey results. Take Tunisia for example; surveys reliably show 99% Muslim. Iran is not a mere 32% Shia.

Y'all, we even have surveys done in Iran: by Pew, by the World Values Survey program, by others..... *nobody* finds less than 85% Shia Muslim in Iran.

I mean look if 8% of literate Iranians are Zoroastrians, that would imply 4 million Zoroastrians.

I regret to inform you all that there are not 4 million Zoroastrians.

I regret to inform you all that there are not 4 million Zoroastrians.

It would be extremely interesting and fun if there were actually 4 million Zoroastrians!

Alas, there are in fact not 4 million Zoroastrians.

Alas, there are in fact not 4 million Zoroastrians.

There are other red flags. 10% of the respondents had personally participated in surveys by this same group before in the past, and it's a group heavily composed of exiles and refugees. That almost certainly explains the religious mix.

Beyond that, only about 50% of Iranian adults use social media, and the survey was distributed via social media. So it's *more* plausible the data represents the opinions of Iranians *who use social media*.

But even there, the selection bias and snowball approach is just very problematic.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter