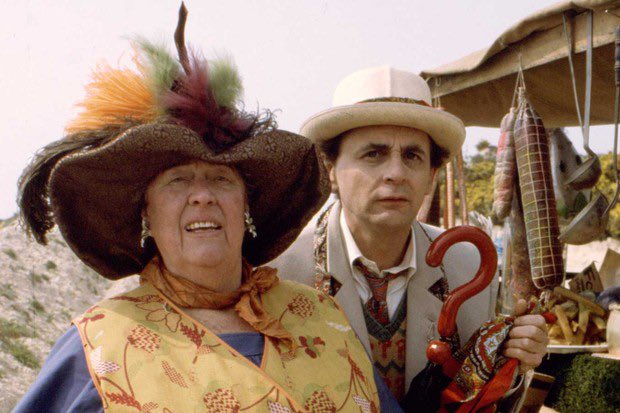

#NowWatching “The Greatest Show in the Galaxy.”

I’d argue that it’s among the most underrated serials in the history of #DoctorWho, along with “The Ribos Operation”, “Warriors’ Gate” and “The Awakening.”

It’s a masterpiece.

I’d argue that it’s among the most underrated serials in the history of #DoctorWho, along with “The Ribos Operation”, “Warriors’ Gate” and “The Awakening.”

It’s a masterpiece.

There are plenty of genuinely hated McCoy era stories like “Silver Nemesis” and “Time and the Rani”, plenty of divisive ones like “Paradise Towers”, “The Happiness Patrol” and “Ghost Light” and some beloved ones like “Remembrance of the Daleks” or “Curse of Fenric.”

I find it fascinating how rarely “Doctor Who” fans talk about “The Greatest Show in the Galaxy”, because it’s fantastic.

Even the production is top notch. The asbestos discovery at the BBC studios forced the crew to shoot it in the parking lot, lending it a great atmosphere.

Even the production is top notch. The asbestos discovery at the BBC studios forced the crew to shoot it in the parking lot, lending it a great atmosphere.

“I thought you’d be interested in the circus.”

“Nah. Kid’s stuff.”

“The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” is, like a lot of “Doctor Who”, a potent metaphor for the show itself.

In particular, the idea of an institution past its glory days, gathering dust, becoming a graveyard.

“Nah. Kid’s stuff.”

“The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” is, like a lot of “Doctor Who”, a potent metaphor for the show itself.

In particular, the idea of an institution past its glory days, gathering dust, becoming a graveyard.

Indeed, the circus metaphor seems particularly pointed given McCoy’s own history as a performer, even if he was never a conventional circus performer.

He was largely presented in the press as a man who shoved ferrets down his pants before being cast in the role.

He was largely presented in the press as a man who shoved ferrets down his pants before being cast in the role.

(There’s also probably something self-aware in the introduction of the painfully hip “rapping ring master.”

After all, the Seventh Doctor engaged repeatedly with black music, like blues in “The Happiness Patrol” or jazz in “Silver Nemesis.”

Self-criticism, maybe?)

After all, the Seventh Doctor engaged repeatedly with black music, like blues in “The Happiness Patrol” or jazz in “Silver Nemesis.”

Self-criticism, maybe?)

Crucially, though, the Cartmel era is particularly interested and engaged with the idea of “Doctor Who” as children’s entertainment.

“Paradise Towers” is “High Rise”... but for kids. “The Happiness Patrol” is fascism reimagined as a kid’s game show, right down to the gunging.

“Paradise Towers” is “High Rise”... but for kids. “The Happiness Patrol” is fascism reimagined as a kid’s game show, right down to the gunging.

Ace’s character arc is largely built around the idea that Ace is not a real teenager, but a sidekick from a children’s television show.

She then crashes into the real world and grows into an actual woman, and the contrast or tension between those two ideas.

She then crashes into the real world and grows into an actual woman, and the contrast or tension between those two ideas.

“The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” suggests that something rotten has taken root in “the Psychic Circus”, as if something monstrous is stirring in the collective subconscious, reflected in our media and entertainment.

Has British culture become warped and monstrous?

Has British culture become warped and monstrous?

“She apparently thinks we're a pair of undesirable intergalactic hippies. We must try and convince her we're nice, clean-living people who eat up all our fresh fruit and pay our way.”

“The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” interrogates the legacy of the sixties, as a sixties show.

“The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” interrogates the legacy of the sixties, as a sixties show.

People often talk about “Remembrance of the Daleks” and “Silver Nemesis” as the obvious companion pieces in the twenty-fifth season, and that makes sense. They have similar plots and returning villains.

But “The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” extends the themes of “Remembrance.”

But “The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” extends the themes of “Remembrance.”

“Remembrance of the Daleks” and “The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” are both stories about using the twenty-fifth anniversary as an excuse for “Doctor Who” to cast its gaze backwards and engage with the legacy of the sixties.

What has changed since then? What hasn’t?

What has changed since then? What hasn’t?

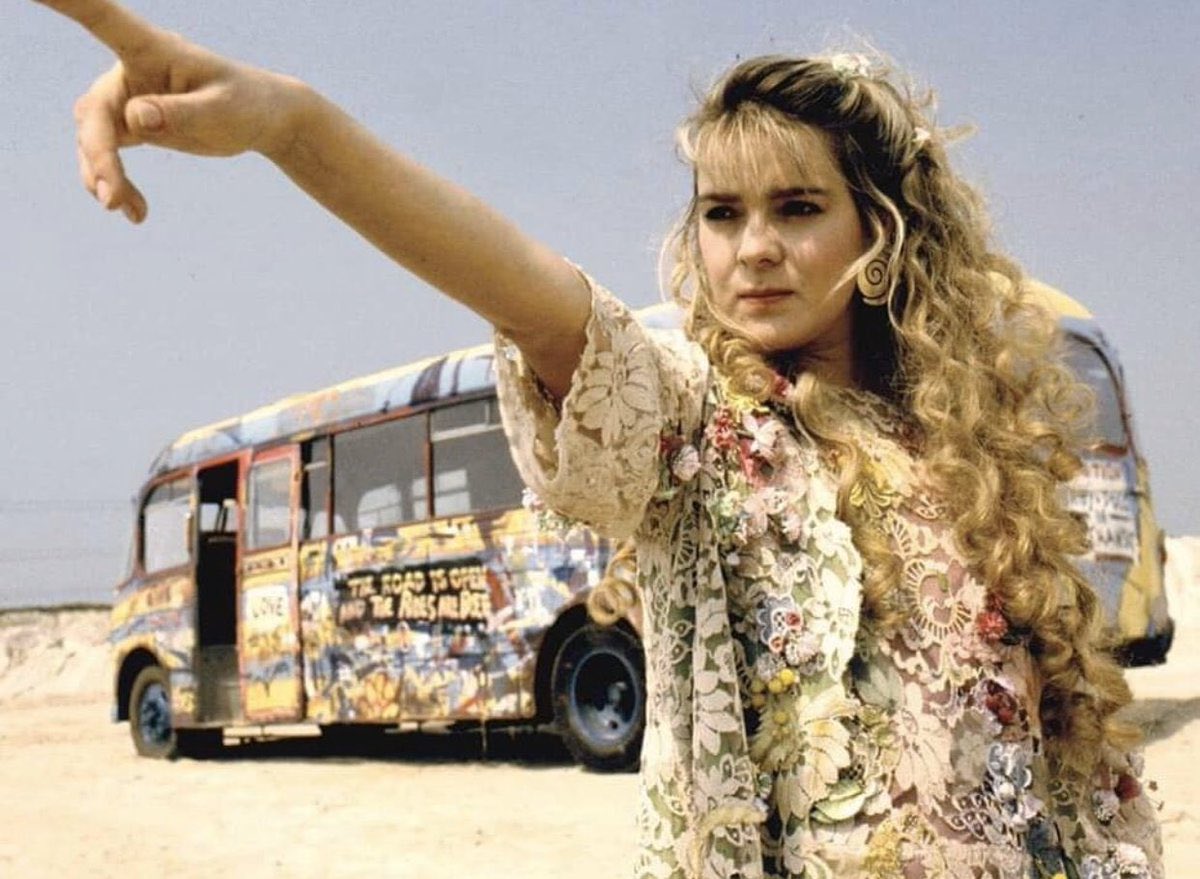

“The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” embraces the iconography of the sixties counterculture: the bus, the hippies, the idea the circus is “psychic.”

However, it looks at how that iconography has rotted, how that generation sold out, settled down, became corrupted.

However, it looks at how that iconography has rotted, how that generation sold out, settled down, became corrupted.

Again, this is hardly a radical idea.

People had been asking these questions about the counter-culture since the seventies.

The remake of “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” is about watching flower power transform into yuppie-dom in San Francisco.

People had been asking these questions about the counter-culture since the seventies.

The remake of “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” is about watching flower power transform into yuppie-dom in San Francisco.

But still, it’s interesting to see “Doctor Who” interrogate this idea, as a show that had been running (mostly) continuously since the early sixties.

More than most other television shows, “Doctor Who” had a thread from 1963 to 1988. And it could pull at it.

More than most other television shows, “Doctor Who” had a thread from 1963 to 1988. And it could pull at it.

Indeed one of the great things about the twenty-fifth anniversary season, in contrast to the tenth or twentieth, was that Andrew Cartmel and his crew actually seemed to engaged with the passage of those twenty-five years and what they meant beyond returning monsters.

“The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” is not particularly subtle in its condemnation of this sold out counterculture - because subtext is for cowards.

In case the audience misses the subtext, there’s even an old hippie bus run aground, scrawled with graffiti: “Give Some Money.”

In case the audience misses the subtext, there’s even an old hippie bus run aground, scrawled with graffiti: “Give Some Money.”

As an aside, buses run aground and destroyed is an interesting recurring motif in the Andrew Cartmel era, also appearing in “Delta and the Bannermen.”

It suggests a world and a universe off-course, broken down, going nowhere fast. Reflecting the show’s mood and outlook.

It suggests a world and a universe off-course, broken down, going nowhere fast. Reflecting the show’s mood and outlook.

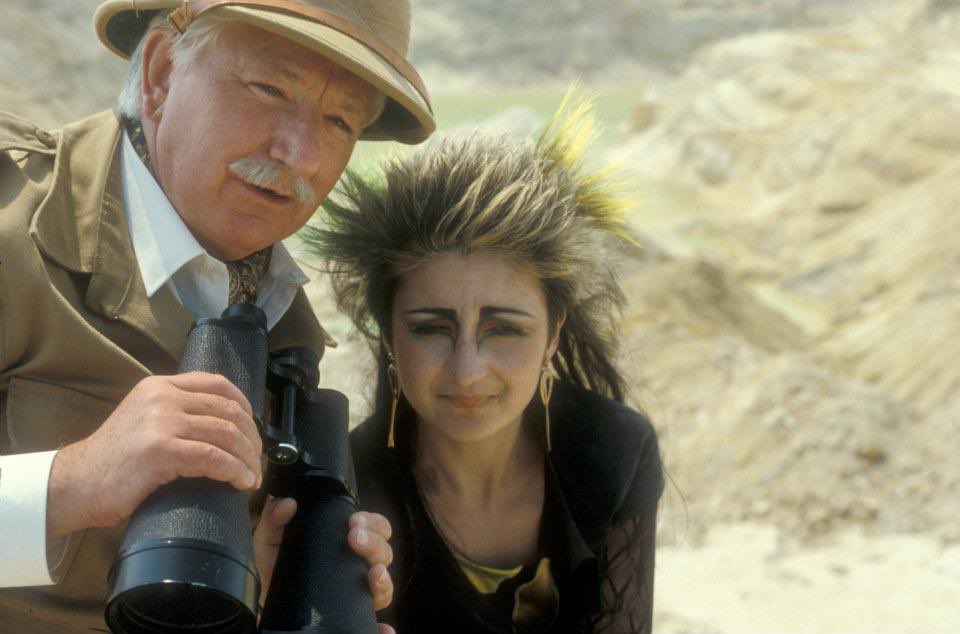

“I am Captain Cook, the eminent intergalactic explorer. You happen to have heard of me, old boy?”

One of the bolder things about the Cartmel era is that the Doctor himself is not exempt from this interrogation.

The show is constantly contrasting the Doctor with alternates.

One of the bolder things about the Cartmel era is that the Doctor himself is not exempt from this interrogation.

The show is constantly contrasting the Doctor with alternates.

“The Happiness Patrol” contrasted its proactive Doctor with its passive Census Taker, for example.

“Ghost Light” will drop the Doctor into an attic filled with Victoriana, suggesting a particular context for the character.

“Ghost Light” will drop the Doctor into an attic filled with Victoriana, suggesting a particular context for the character.

The Doctor himself is a peculiarly British archetype, a patriarchal male explorer with a glamourous young female assistant to whom he can explain the world.

He lands in strange places, and upends the established order. The implications are not entirely comfortable.

He lands in strange places, and upends the established order. The implications are not entirely comfortable.

The show has arguably been unpacking that idea since the Peter Davison era.

Under Andrew Cartmel, “Doctor Who” begins very consciously and deliberately interrogating its lead character and the archetype that he represents.

Under Andrew Cartmel, “Doctor Who” begins very consciously and deliberately interrogating its lead character and the archetype that he represents.

This interrogation of the Doctor as archetypal, pseudo-colonial and patriarchal figure continues from Andrew Cartmel’s tenure through Russell T. Davies and Steven Moffat.

Moffat upends the Doctor/companion power dynamic and Chibnall has the Doctor regenerate into a woman.

Moffat upends the Doctor/companion power dynamic and Chibnall has the Doctor regenerate into a woman.

(There’s an argument, for another time, that Chibnall rendering the Thirteenth (and first woman) Doctor as strangely passive is a bizarre over-correction along this trend.

But that is a discussion for another time.)

But that is a discussion for another time.)

“The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” explores this side of the Doctor by contrasting him with Captain Cook, who is explicitly named to evoke a relic of Britain’s colonial past.

Cook (or “the Captain”) even has a companion in Mags, whose name seems deliberately similar to Ace.

Cook (or “the Captain”) even has a companion in Mags, whose name seems deliberately similar to Ace.

“What about yours?”

“I never think of Ace as a specimen of anything.”

“Keep your shirt on, Doctor. Everything's a specimen of something.”

Cook’s relationship with Mags is explicitly paralleled with the Doctor’s relationship with Ace.

Cook sees Mags as a tool, not a person.

Cook’s relationship with Mags is explicitly paralleled with the Doctor’s relationship with Ace.

Cook sees Mags as a tool, not a person.

A less complicated and interesting version of “Doctor Who” would treat this as an obvious point of contrast, insisting that the Doctor isn’t like Cook because he doesn’t treat Ace as a tool.

But his use of Ace in, say, “Curse of Fenric” complicates this comparison.

But his use of Ace in, say, “Curse of Fenric” complicates this comparison.

The Seventh Doctor is a decidedly ambiguous iteration of the Time Lord. Part of that ambiguity stems from the reworking of his character in “Remembrance of the Daleks.”

But another part stems from the show’s willingness to put the archetype in context.

But another part stems from the show’s willingness to put the archetype in context.

“Is there no end to you wierdos?”

“The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” also codifies a recurring motif of the McCoy era. It isn’t just a surreal or unusual setting, it’s populated by surreal and contrary figures.

“The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” also codifies a recurring motif of the McCoy era. It isn’t just a surreal or unusual setting, it’s populated by surreal and contrary figures.

The weird elements in “The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” aren’t just the circus clowns and acts, like one might expect.

The visitors and tourists are all weird and cartoonish, heightened. You can sense the influence of 2000 A.D. and British comics on the show.

The visitors and tourists are all weird and cartoonish, heightened. You can sense the influence of 2000 A.D. and British comics on the show.

Again, you can easily draw a straight line from this aspect of stories like “The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” to the futuristic stories overseen by Russell T. Davies like “The End of the World” or “Gridlock.”

World inhabited by all manner of disparate and surreal creatures.

World inhabited by all manner of disparate and surreal creatures.

While Davies famously blew through a large portion of the first season budget on “The End of the World”, the surreal and colourful characters in “The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” are an effective budget saving measure.

After all, most of the costumes are (individually) familiar.

After all, most of the costumes are (individually) familiar.

After all, the BBC likely had plenty of circus, clown, colonial explorer, hippie and nerd costumes in storage. Because few of them are odd on their own.

But put them together and you end up with something delightfully strange and uncanny.

But put them together and you end up with something delightfully strange and uncanny.

“I hope he's better than the last one.”

“Couldn't be much worse.”

If the Psychic Circus is a metaphor for the sorry state of “Doctor Who” in the late eighties, sixties culture stuck aground, then there’s something interesting in how “The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” frames it.

“Couldn't be much worse.”

If the Psychic Circus is a metaphor for the sorry state of “Doctor Who” in the late eighties, sixties culture stuck aground, then there’s something interesting in how “The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” frames it.

After all, the central horror of “The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” is the Psychic Circus transformed into a charnel house to entertain a stereotypically middle class and unengaged audience.

In case you don’t get the subtext, acts are dependent on audience ratings to survive.

In case you don’t get the subtext, acts are dependent on audience ratings to survive.

After all, Sylvester McCoy inherited the role at a time when “Doctor Who” had a particularly antagonistic relationship with its audience.

The Colin Baker years, including the “Doctor in Distress” fiasco, had cost the show a lot of goodwill. The show’s future was in doubt.

The Colin Baker years, including the “Doctor in Distress” fiasco, had cost the show a lot of goodwill. The show’s future was in doubt.

It’s hard not to read “The Greatest Show in the Galaxy” as an extended metaphor arguing that the version of “Doctor Who” that might scrape by for a few more seasons appeasing that hostile mainstream audience wasn’t worth making.

“Doctor Who” should go out on its own terms.

“Doctor Who” should go out on its own terms.

There’s a credible argument that the last couple of seasons of “Doctor Who” were a cult show, rather than a populist one.

However, they were also brilliant, provocative, engaged and necessary for the show’s growth and evolution in its time off the air.

However, they were also brilliant, provocative, engaged and necessary for the show’s growth and evolution in its time off the air.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter