I am excited to talk about a new paper that I helped organize describing the ways we characterize @LIGO detectors and improve their sensitivity to gravitational waves! https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.11673

We talk about the types of noises that impact LIGO and how we know that the GWs that LIGO sees aren’t actually caused by anything here on Earth! There’s lots of different types of noises that show up in LIGO data, but I’ll talk about some of the highlights.

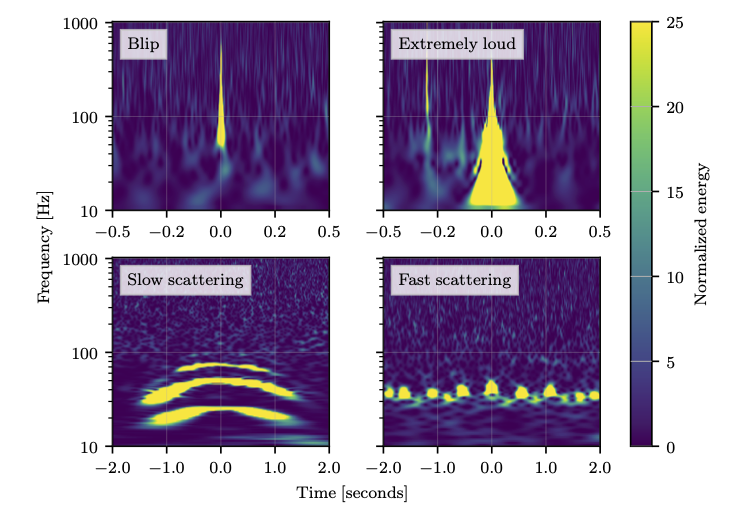

Every few minutes, a loud burst of noise shows up in the LIGO data. Most of the time, these burst aren’t from GWU, but rather from instrumental sources. We call these glitches, and they come in a wide variety of types.

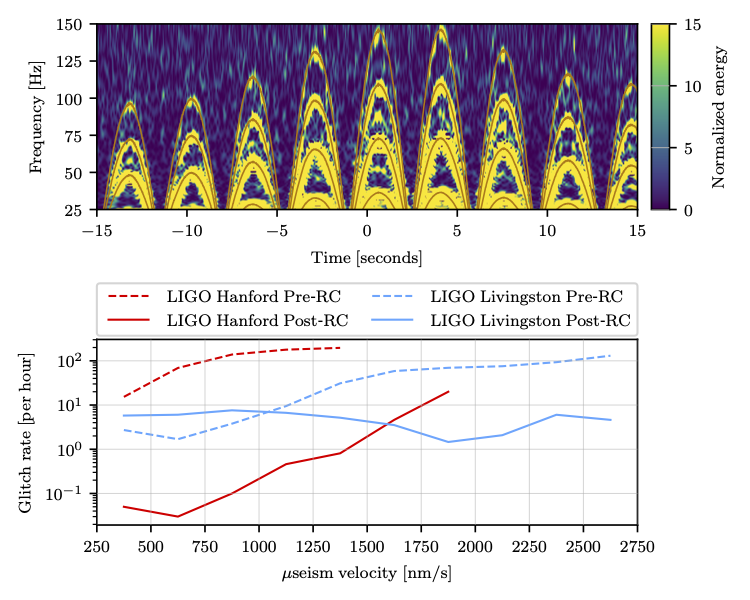

One of the worst sources of glitches is from scattered light. This creates arch shapes in the data that you can see below. One of the biggest improvements in the last observing run was tracking down where some of the scattered light was coming from and stopping it.

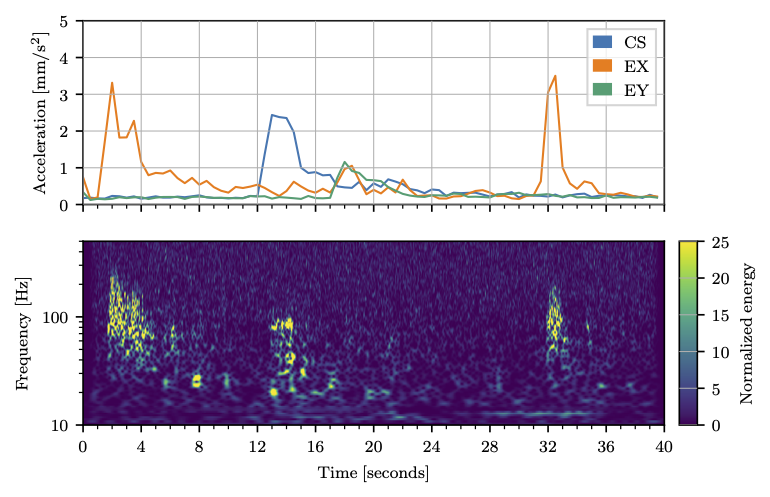

LIGO also is impacted by thunder which shakes the entire detector and adds a rumbling sound to the data. LIGO is so big that the sound from a single lightning strike can arrive at each end of the detector multiple seconds apart!

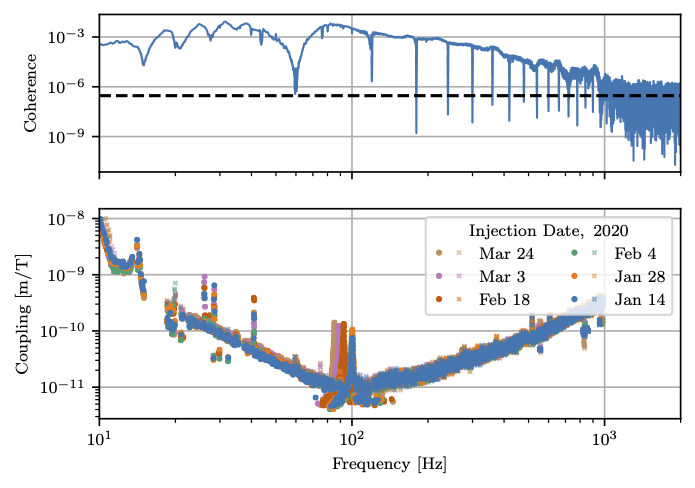

Another concern is magnetic noise that is correlated between both LIGO sites. The main source of these correlations is from the Earth’s magnetic field! Thankfully the noise is very weak and doesn’t impact our GW detections, but we still keep a close eye on it.

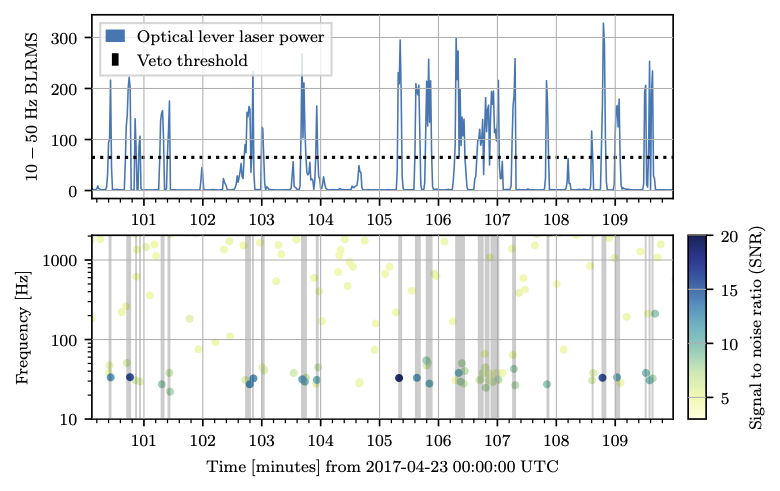

When we do see glitches in the data, we do our best to flag these time periods so that we don’t mistake them for a real GW. In this case, whenever there was a spike in the optical lever laser power, there was also a glitch!

Another way we address glitches is by removing a small amount of data around the glitch, called "gating." In the last observing run, gating loud glitches was a very important part of increasing the sensitivity of LIGO to very weak, continuous sources of GWs.

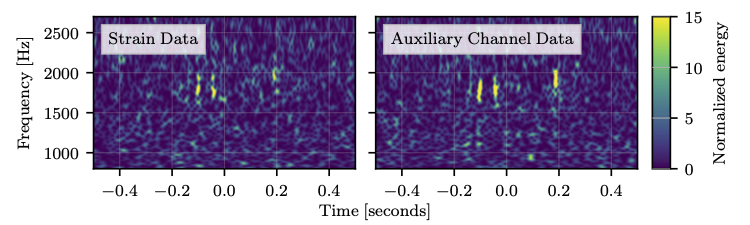

Whenever we think we might have seen a gravitational wave, we perform lots of tests to check if the signal could actually be a glitch. Most of the time we confirm that the event is a real signal, but ever so often we find out that we really just discovered a new glitch.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter