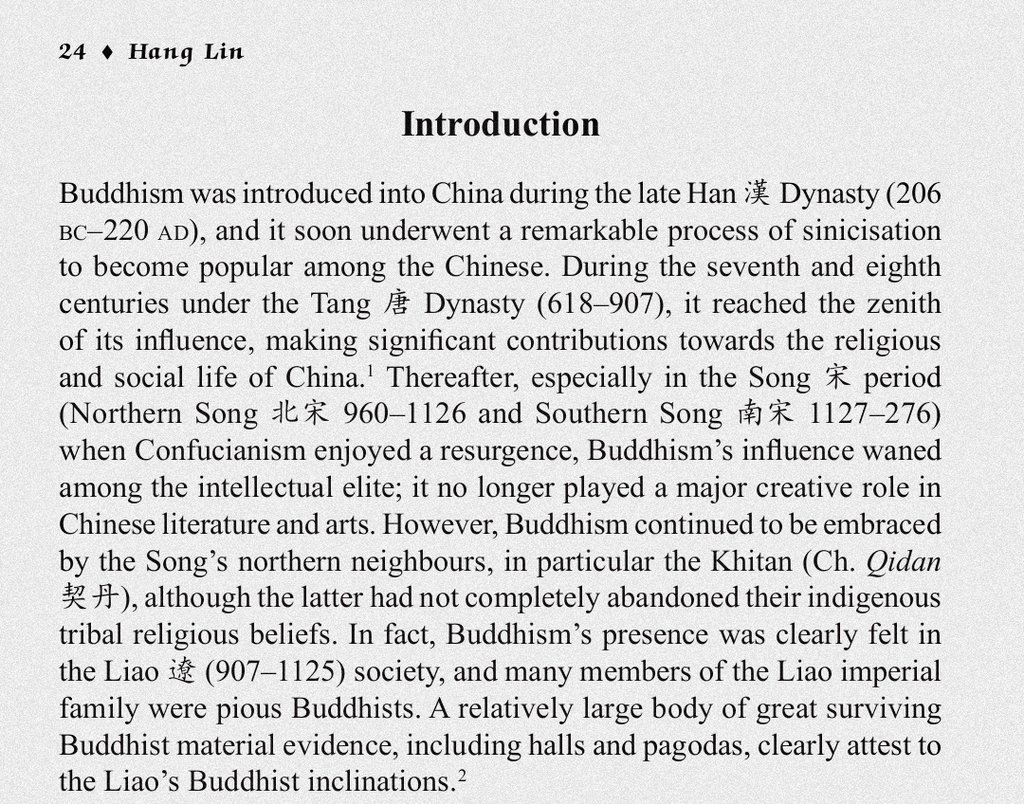

This Buddhist statuette/figurine is from the Khitan Liao Dynasty (916-1125)

The empire during its heyday stretched from modern day Kazakhstan all the way to the Sakhalin Island, and ruled a big chunk of northern China.

The Xiongnu empire was a polyethnic tribal confederation, but their exact imperial structure remains poorly understood.

Later nomadic empires’ inability to maintain territory unity was foretold in the Xiongnu’s fragmentation.

The Xiongnu empire’s collapse triggered further Turkic and Hunnic expansion into central and western Eurasia.

Taizong was a veritable Chinese kaghan, a great horseman and warrior, dynamic enough to murder his brothers and depose his father to get to the throne.

The Turkophile crown prince Li Chéngqián (李承乾, 618 – 645) died in exile for plotting against his father.

The kaghan's blood can not be shed; when one of the Ashina line was executed, it was by strangulation.

By the late 6th century, the ruler of the East and West had fallen out with each other over succession issues.

The volume of resources extorted from China meant that the Uyghurs had too much wealth not to have a permanent fortified capital.

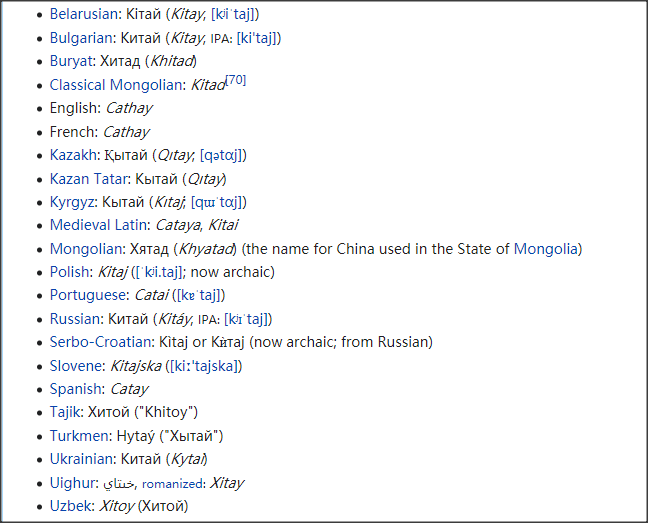

After the Uyghurs fell in 840 at the hands of the Kyrgyz, the Tang sank into internal revolt within a generation.

As Central Asia began to become part of the Muslim World, Islam began to influence the indigenous population.

Source,

The Turks in World History

By Carter V. Findley (Ohio State University)

https://books.google.com/books?id=ToAjDgAAQBAJ

The Turks in World History

By Carter V. Findley (Ohio State University)

https://books.google.com/books?id=ToAjDgAAQBAJ

Related,

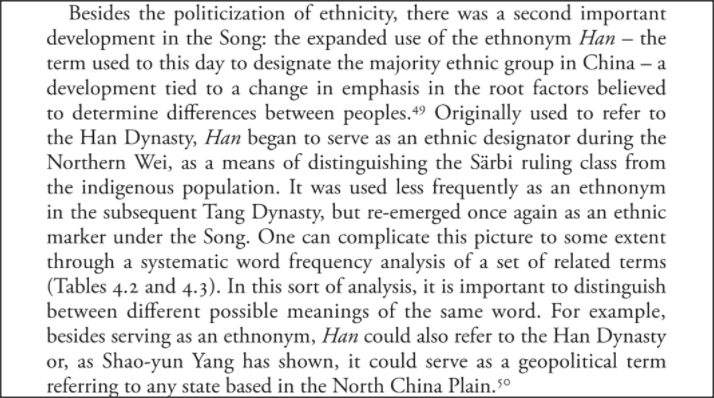

The Origins of the Chinese Nation: Song China and the Forging of an East Asian World Order

By Nicolas Tackett

(page 156)

https://books.google.com/books?id=G8k-DwAAQBAJ

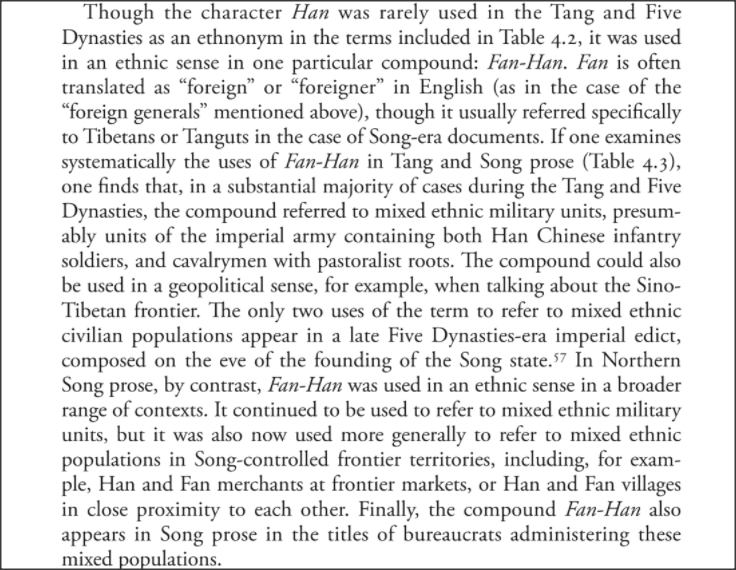

The Origins of the Chinese Nation: Song China and the Forging of an East Asian World Order

By Nicolas Tackett

(page 156)

https://books.google.com/books?id=G8k-DwAAQBAJ

The term 蕃汉 (Fan-Han) referred specifically to Tibetans or Tanguts in the case of Song-era documents.

"To transform Song China into an ethnic Han state, it was necessary to homogenize the population by concealing the non-Chinese backgrounds of top officials, while simultaneously clarifying ethnic boundaries in frontier regions."

Numerous regimes during the 10th century, Sinitic or not, made alliances with the Khitans indiscriminately in their struggles to survive within a complex multi-state system.

Throughout the Sui-Tang period, the court was far more interested in preserving the authority and prestige of the regime than in seizing 'former' territory.

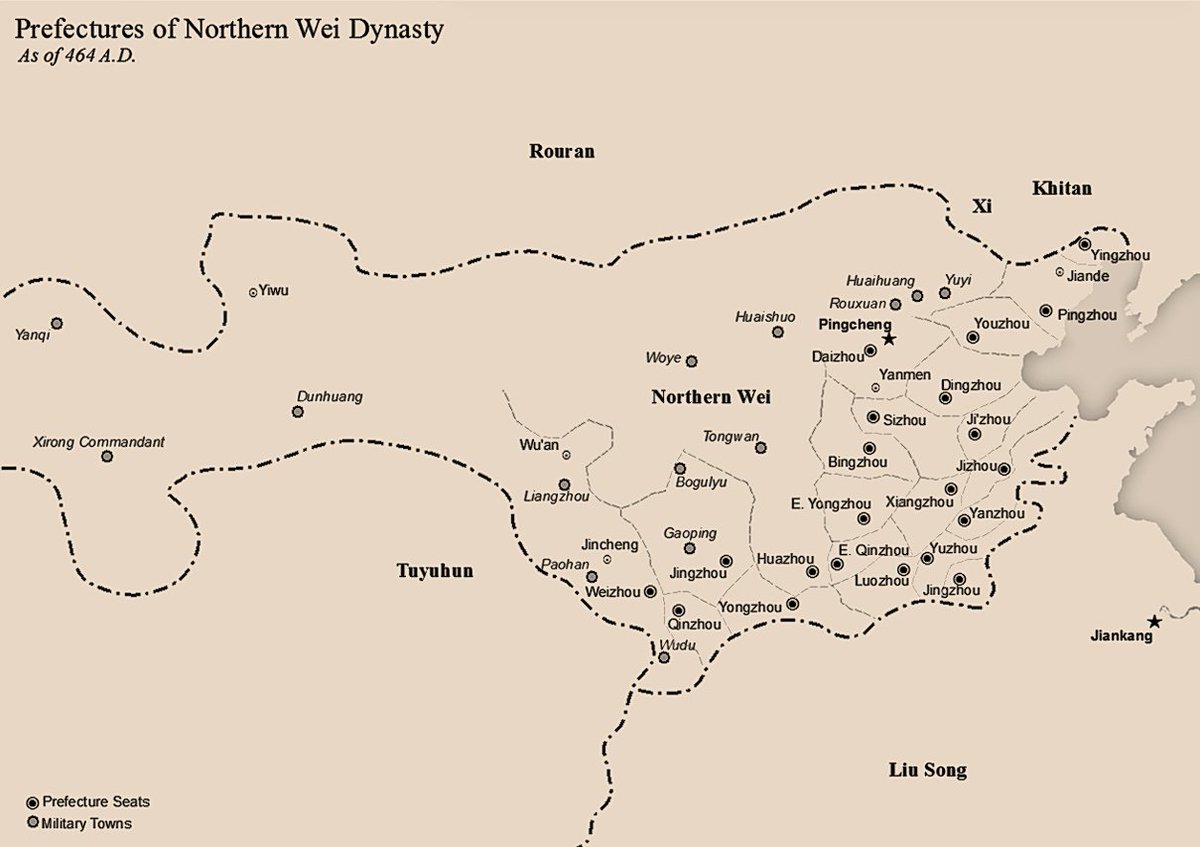

Military forays into the north during the Northern Wei Dynasty were spurred by military men seeking to expand their power and influence, not with a mind toward the reconquest of lost Han territory.

In Europe, claims to territory based on ethno-cultural principles ultimated stemmed from Romantic ideas of self-determination.

In Song-dynasty China, they derived from the concept of grand unity (大一统).

In Song-dynasty China, they derived from the concept of grand unity (大一统).

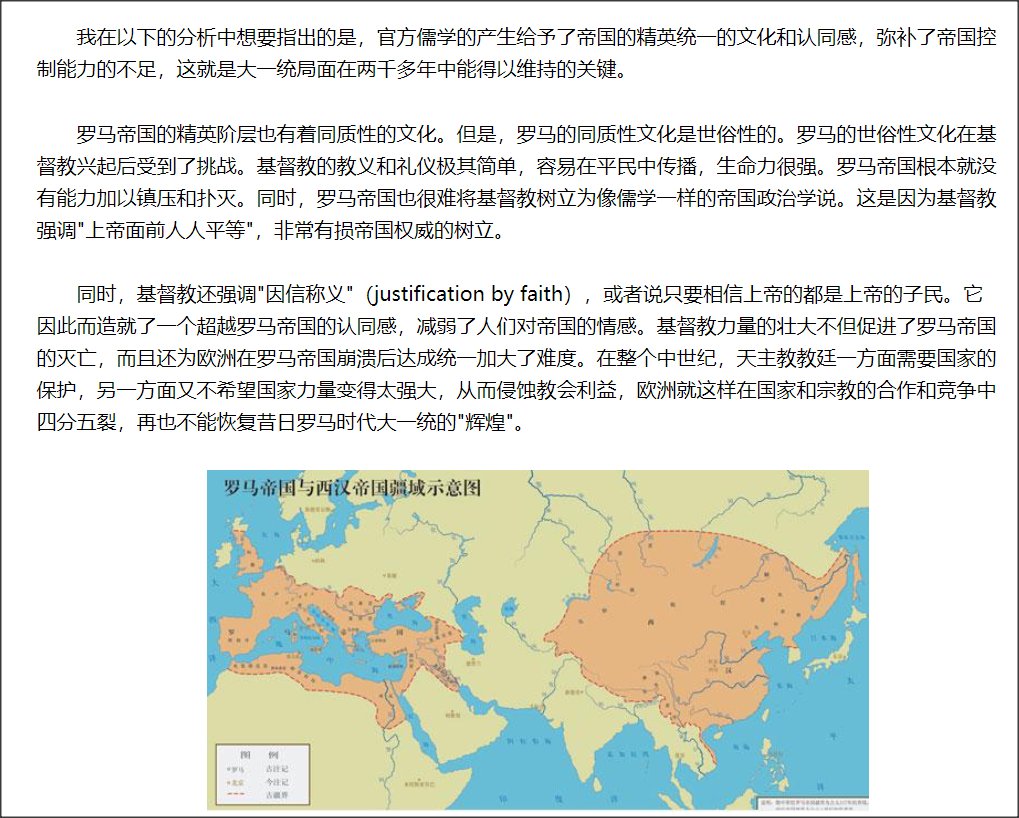

赵鼎新:官方儒学的产生给予了帝国的精英统一的文化和认同感,弥补了帝国控制能力的不足,这就是大一统局面在两千多年中能得以维持的关键。而基督教力量的壮大不但促进了罗马帝国的灭亡,而且还为欧洲在罗马帝国崩溃后达成统一加大了难度。

https://www.guancha.cn/ZhaoDingXin/2018_05_17_457070_s.shtml

https://www.guancha.cn/ZhaoDingXin/2018_05_17_457070_s.shtml

中国每个朝代的倒台原因非常不同,但是新的大一统局面形成的背后却都有着相似的原因,那即是统治阶级在上台后马上会发觉儒学是最为适合的统治意识形态。儒学为中华帝国提供了一个同质性的文化和认同感基础,从而在很大程度上弥补了古代帝国控制能力有限这一局限。

先秦中国和前现代欧洲有很大不同。在欧洲,在战争越打越大的同时,商业竞争越来越激烈,商人的权力也不断越高。商人与在战争中不断加强的国家之间的冲突和合作为君主立宪、代议制民主、民主国家和工业资本主义的兴起铺平了道路,而先秦中国主导社会变迁的动力主要是战争。

儒学作为官方意识形态是逐渐建立起来的,并且在东汉才逐渐完成了所谓的圣典化 (canonization)。董仲舒就是在这圣典化过程中被吹大的,在《汉书》中董的传记占了整整一章。最后,汉武帝虽然把儒学上升成为国家意识形态,但是他用的人杂七杂八,什么样子的都有,他的大量政策也是以法家为主。

古代社会的主流价值观都是宗教或类宗教的价值观,不论它是儒学,佛教,伊斯兰教,还是基督教。前现代各个文明区别如此之大,一个重要原因就是因为它们有着不同的宗教。相较于其它宗教,儒学作为国家统治工具有着特殊的“优越性”。

儒学讲三纲五常,它把社会不平等看做正常,只不过要求德位相匹配。不像基督教,讲上帝面前人人平等,国君地位总是有点危险。《古兰经》强调部落力量,给强势的部落存在提供了合法性。印度教给了一个没有流动的种姓社会一个合法性和功能,国家几乎成了多余,所以印度长期不能统一。

古代西方的国家与基督教的关系较之中国的国家与儒学的关系要来得平等,但是这平等却给西方国家和宗教之间带来了很大的紧张:统治者想摆脱教会的控制,而教会对其它宗教或者是不同教义的教会都具有很低的容忍度。基督教世界于是就充满了宗教战争和迫害。

如果不站在中国中心主义立场的话,你会发现直到晚清中国还在扩张,还在加强统治能力。内边疆在改土归流,新疆建立了行省。直到19世纪末,清朝还在加强对蒙疆的控制,军事实力也在增强。但是清朝碰到了先前的中原王朝所未遇到的问题,它的挑战者不再是来自北方的游牧部落,而是正在经历工业革命的西方。

如果中国最后一个皇朝的统治者是汉人的话,革命也许就能避免。满清政权始终面临着两个难以调和的问题:救满清和救中国。清统治者在改革强国的同时还想加强满人的权力,以抗衡在甲午失败后不断上升的汉人民族主义思潮,边缘化袁世凯、张謇、汤化龙这样的汉人精英的权力。

世界上所有的宗教在现代化的冲击下都有所衰退。这个衰退,西方学者搞错了,把它看成了“世俗化”。其实在最近到几十年里,除了民族主义之外的所有大型世俗意识形态(从社会主义到自由主义)在世界范围内都在走下坡路,取而代之的是宗教的复兴。但是,其它宗教在复兴,偏偏儒学复兴不起来。

这背后的原因就是现代化并没有摧毁其它宗教的制度基础 (比如和基督教相应的教会组织和资源),这些宗教因此都能逐渐适应现代社会,并在现代条件下找出生存和发展的道路。唯独儒学,这个在传统世界无比强势的思想体系在现代化过程中衰退成了一个无根的哲学,因为它的制度基础已经被摧毁了。

持有道德史观的学者热衷于从历史中找正义找道德。搞过了,特别和权力与利益结合后就会促使造假。当权力和利益需要烈女时,社会就会突然出现大量的烈女;当权力和利益需要雷锋时,社会上就会到处是活雷锋;而当权力和利益需要天才和特异功能时,具有各种“天才”和“特异功能”的人就会铺天盖地而来。

从马克思主义到社会达尔文主义再到自由主义等等的各种进步史观都是十九世纪欧洲人自我感觉良好的产物。十九世纪的欧洲人打仗厉害再加上生产能力强,欧洲的思想家就把他们在经济和军事方面的优势当成了历史进步,把其它地区的国家看成野蛮或落后。可怕的是其它国家的精英还不得不接受进步史观。

人类历史上有很多重大的同构节点,都发生在军事和经济竞争占主导的时期。比如战国时代的法家改革,一个国家搞了改革,别的国家不搞就不行。并不是法家代表进步,而是打仗的需要。

历史不会有一个统一的终结,因为人类还在政治和意识形态层面上展开竞争。意识形态层面上的竞争既没有明确的输赢准则 (想象一个基督徒和佛教徒辩论哪个宗教更优越会有什么结果),也不会促进社会的积累性发展。当意识形态竞争和政治竞争在社会中成为主导时,该社会就不会有很强的积累性发展动力。

To read » The Confucian-Legalist State: A New Theory of Chinese History - Dingxin Zhao - Google Books https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Confucian_Legalist_State.html?id=wPmJCgAAQBAJ

The Confucian-Legalist political system that emerged in China during the Western Han lasted for two millennia.

By no means does “lasted” imply that this political system underwent no significant changes over that time.

By no means does “lasted” imply that this political system underwent no significant changes over that time.

It was precisely because of this resilience that China, for better or worse, did not develop industrial capitalism as Western Europe did, notwithstanding China’s economic prosperity and technological sophistication beginning with the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127).

Bowing to the current dominant beliefs that history is non-teleological, non-directional, and contingent, historians today tend to focus on brief time periods and specific aspects of history.

Imperial China was the only world civilization where transcendental world religions exerted no major influence on politics and where a strong state exhibited great tolerance toward, and even actively sponsored, countless kinds of religious beliefs.

In contrast with early-modern European cities, the cities of late imperial China, even though many of them were highly commercialized, were governed by state-appointed officials, and merchants were never able to carve out an independent role in politics.

By the late Eastern Zhou period,

Legalism, a philosophy that justified heavy-handed state power, became the prevailing political philosophy;

armies came under the firm control of governments;

and merchants were unable to turn their wealth into political power.

Legalism, a philosophy that justified heavy-handed state power, became the prevailing political philosophy;

armies came under the firm control of governments;

and merchants were unable to turn their wealth into political power.

Both early China and second-millennium Europe were caught up in multi-state competition, and the military competition in both societies generated enormous social dynamism.

Europe developed in the direction of constitutional government and industrial capitalism; China, toward a bureaucratic empire.

Most significantly, the competition among the states, churches, and the aristocracy in medieval Europe effectively checked state (political) power.

The fierce military and economic competition in Europe compelled all the political actors to enhance their capacity to organize, to tax the people, and to extract natural resources.

That compulsion imbued European society with a strong developmental character.

That compulsion imbued European society with a strong developmental character.

The balance between military competition economic competition, in conjunction with the influence of religious actors in Europe, allowed churches, universities, cities, and guilds to form themselves into corporate entities with protected rights and roles in society.

Together and in competition with each other, these power actors gave rise to bureaucratic states in which power was checked and balanced by a constitution.

They also promoted bourgeois power and ideologies glorifying privately oriented instrumental rationalism.

They also promoted bourgeois power and ideologies glorifying privately oriented instrumental rationalism.

The aristocracy since the Eastern Zhou period has been increasingly incapable of competing with the state as warfare expanded in scale, a meritocratic bureaucracy took root, and Legalism became the prevailing state ideology.

The Qin empire, after subduing all the other states to its rule, controlled a battle-hardened military of over half a million warriors, a highly sophisticated bureaucracy, and an advanced transportation and communication system.

Yet only 15 years after its inception, this mighty empire was overthrown, making it the shortest-lived major dynasty in Chinese history.

The synergistic relationships among Legalist ideologies and regulations and military mobilization greatly strengthened the Qin state, encouraging Qin rulers to base their control on harsh Legalist ruling techniques rather than on state-society cooperation and normative consensus.

The lessons influenced early Western Han politics to form a highly stable crystallization of the four power sources:

the Confucian-Legalist state,

a system of government that merged political and ideological power,

harnessed military power,

and marginalized economic power.

the Confucian-Legalist state,

a system of government that merged political and ideological power,

harnessed military power,

and marginalized economic power.

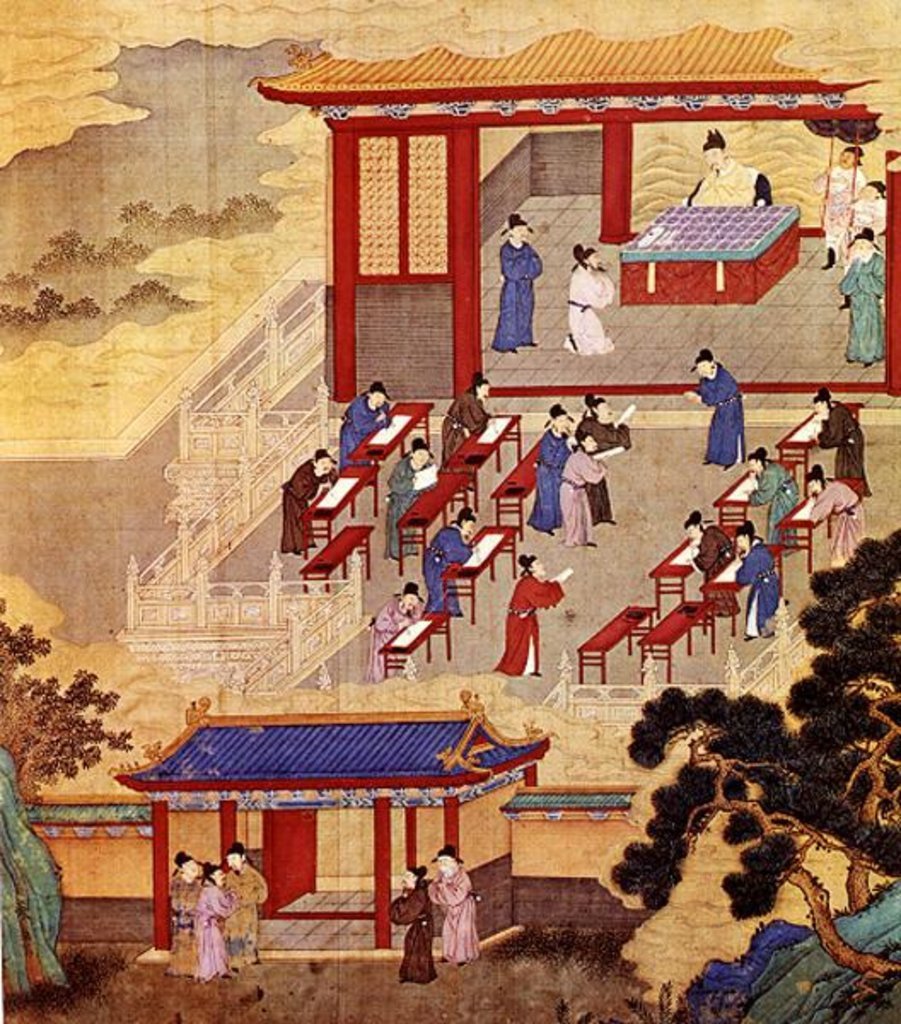

In the Confucian-Legalist state, the emperors accepted Confucianism as a ruling ideology, while Confucian scholars supported the regime and supplied meritocratically selected officials who administrated the country using an amalgam of Confucian ethics and Legalist techniques.

As the Confucian-Legalist system achieved a more developed form during the Song dynasty (960–1279), China became home to a form of “compulsory cooperation” that was more sophisticated than the Roman counterpart.

Whereas the Roman elites shared only a similar secular culture, the Chinese elites were inculcated with quasi-religious Neo-Confucian values.

The Roman rulers tried to but could neither suppress nor co-opt Christianity after its rise; the Chinese rulers on the other hand actively adopted Confucianism as a ruling ideology.

With such a structure in place, it was in the interests of any new ruler of China, whether indigenous or foreign, to seek the cooperation of the Confucian elite and to amend rather than overturn the Confucian-Legalist political arrangement.

Imperial Confucianism as it emerged during the Han dynasty was more a this-worldly ethical system than a transcendental religion.

Yet it also incorporated many religious elements common to ancient China, such as ancestor worship, a concept of heaven as a conscious overseer of the affairs of the human realm, divination, predetermination, and yin-yang cosmology.

In many ways, the role of Confucianism in China was similar to that played by Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism in other societies.

在今天,合法性则涵盖了国家权力来源的各种不同面向,包括法理性的和非法理性的。对于任何一个国家来说,合法性都是一个根本性的,同时也是一个非常实际的政治问题。这是因为统治者掌握着被统治者所没有的、带有强制性的权力,但他们在人数上相对于广大被统治民众来说却永远处于绝对少数。

古代中国曾出现过大量的、从今天来看是有关国家合法性的论述。《尚书》中的“天命”观、孔子的“正名”和“仁”、荀子的“水能载舟、亦能覆舟”、陆贾的“马上能打天下,却不能治天下”这些都可以被看作古代中国有关国家权力合法性的理论。

一个国家合法与否不在于知识精英的评判,而在于普通民众的感受。西方民众对政府的支持度经常会低达百分之十几,但是西方民众反感的主要是当政者,而不是西方国家的政体。因此,西方的政客很少因为支持率低而产生合法性危机感或惧怕过政治不稳定。

人有论证自己行动正确性的能力,也有口是心非的能力;人有虚幻意识,往往自以为是,并想扩大自己的影响;针对某一个具体目标,人的动机也并不单纯。因此,当具有这些驳杂性质的人组成社会之后,人的驳杂就会转化为社会组织行为的驳杂和人类所创造的各种日常概念的“不纯性”。

如果国家统治的正当性基于的是一个被大众广为接受的意识形态,这个国家的统治是基于意识形态合法性。如果统治正当性源自国家为大众提供公共物的能力,统治基于的是绩效合法性。如果国家统治的正当性来源于一套被有能力影响政治过程的群体所广泛接受的程序,这个国家的统治就是基于程序合法性。

任何政权都不会把合法性完全建立在单一类型上,或者说任何一个国家的合法性来源都是这三个理想型的混合体。但是,在特定历史时段中,某一理想型合法性会成为一个国家统治最为重要的来源,并在很大程度上定义了这一国家的性质乃至这一国家民众的政治认知模式和政治行为特征。

内在逻辑自洽这一准则决定了成功核心价值观建构的真谛在有所侧重。如果一个国家要搞宗教极端主义,就很难把言论自由和性别平等作为其核心价值观的一部分。如果一个国家想要提倡把社会等级和秩序视为合理的儒学,就很难把追求平等和强调社会冲突的马克思主义也作为核心价值观的一部分。

作为核心价值观来说,宗教就要比某某主义来说更具有稳定性。因为某某主义承诺的东西太具体太容易被证伪,而宗教承诺的“来世”和“天堂”永远不会被证伪。核心价值观和政体形式必须有一定程度的一致性。比如,作为一个保守的伊斯兰教政权,伊朗是不可能把平等、特别是性别平等作为自己的核心价值观的。

从统治者角度来说,宗教和自由主义都是比较容易竖立的价值观;因为宗教贴近了人怕死和喜欢放大自己生命意义的本性,而自由主义则贴近了人自利和工具理性的本性。在民智已开、人员流动很大的现代社会中,失去了宗教性的儒学对于统治者来说就是一个很难树立的核心价值观。

在具有很强意识形态合法性的国家中,大众的政治认知和行为模式会呈现以下一些特色:社会精英会心甘情愿并且带着激情来制造与主流价值观相一致的舆论(从批判的角度可被称之为“制造共识”);民众对符合主流价值观的舆论坚信不疑且为之鼓舞;社会精英和大众都会追求与主流价值观一致的政治正确。

在这样的社会中政治信任极高,但是有的民众却不得不在政治正确的压力和由之带来的各种利益下作出伪装。政治正确的压力达到一定高度后,道德高调就会与社会实际严重脱节,社会走向专制。这类现象发生在威权国家中会被称之为“专政”,发生在民主国家中则被称为“多数暴政”。

为了不使反体制意识形态坐大,国家就势必对社会舆论设限,比如,对媒体从业人员有所要求,但他们会对这些要求产生抵触。当然,国家可以通过金钱来收买一部分媒体从业人员,面对伴随国家权力的各种利益诱惑有些媒体从业人员也会主动向国家靠拢,媒体从业人员中也总会有一些人能认同国家意识形态合法性。

同样重要的是,虽然金钱和利益能收买一些人心,但是在意识形态合法性有严重缺失的情况下,社会一流人才就会不屑于制造共识,而愿意参与制造共识的人往往是一些素质不高的机会主义者。意识形态合法性有严重缺失的情况下制造出来的新闻往往既缺乏专业主义,也不会为民众喜闻乐见。

在意识形态合法性有严重缺失的情况下,社会精英和民众都不会在乎与主流价值观一致的政治正确。由于缺乏政治信任,主流新闻媒体往往不能建构社会舆论,但是政治谣言和小道消息却能盛行。因为没有核心价值观带来的政治正确压力,除了在面对国家暴力时有人会免不了缄口外,他们想讲什么就讲什么。

在现代社会,成功的魅力合法性的建构必须具备两个条件:第一是大多数民众都对该领袖身上体现的意识形态有着强烈的认同;第二是该领袖有着特殊履历。该领袖必须身处一个在当时被广泛认可的“伟大时代”;其二是该领袖有着一个进行有限的包装就可以被神化为“伟大时代缔造者”的履历。

意识形态合法性并不是国家合法性的唯一面向;即使是在革命前夜,即将倒台的统治者也不乏支持者;大众的政治思维和行为模式也并不完全由国家合法性所决定。因此,以上分析的都是理想状态下的社会现象和可能性,而不是任何一个具体国家的情况。

不同的人对国家的要求必然会有不同的和相互冲突的侧重,对国家提供公共物的能力和质量也会有不同评价。但是,人的差异性只会给一个只具有绩效合法性的国家带来更大的麻烦。比如,老人可能还记得起过去的苦难,因而比较容易满足,而青年人就会把今天的“美好”视为理所当然,因此容易产生不满。

古代欧洲身份区分严格,不同阶层之间的流动较小,因此每个阶层(特别是精英阶层)都有比较统一的、并且是清晰的客观标志和主观认同(比如谁是贵族、谁是僧侣等等)。现代社会中每个人的身份趋于多样,并且身份的变动比较大,大量的人(包括处于社会下层的民众)不再有清晰客观的身份标志。

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter