Robinhood is selling order flow. Anyone who has read Flash Boys will agree that it's a joke that it is being allowed. @chamath is right to pass on it for integrity. My bet is that Payment for Order Flow will be banned entirely within a year. A quick glimpse of Flash Boys

The olden days’ image of the stock market is that it’s loud, crowded with traders running around frantically to get to act first on information. Today’s the majority of trading happens through computers located in data centers all over the world.

There used to be only private investors, institutional investors, brokers and one or two exchanges; now there are numerous exchanges as well as several middlemen. Today high frequency traders (HFTs) make up more than half of US stock trades.

They operate in obscurity because their business model depends on being secretive; they profit from taking advantage of others by keeping information hidden from them.

The stock market is fast paced and sensitive to the speed of data transmission. As a result, high-frequency traders (HFT) place their computers as close as possible to those at the stock exchange; this is known as co-location.

This allows HFTs to get information about trades that investors are making before it reaches its destination. They can also issue buy orders for stocks they plan on selling back at a higher price in what’s called front running.

The victims here are investors who pay more money for shares than they would have if there were fair practices in play.

https://twitter.com/tyler/status/1354812210481008640

@tyler

https://twitter.com/tyler/status/1354812210481008640

@tyler

Flash Boys main character Katsuyama worked for RBC (Royal Bank of Canada) for many years – first in Canada and then on Wall Street. The bank is known for its conservatism and focus on value.

In 2006, RBC acquired Carlin Financial Group USA Inc., a firm specializing in electronic trading whose goal was simple: become rich quickly. Katsuyama felt he didn't fit in with the new culture.

He also encountered problems with the market, as every time he wanted to buy stocks they were more expensive and when he wanted to sell them they were cheaper. The other traders on the floor felt the same way.

Katsuyama suspected that someone was manipulating stock prices by taking advantage of how long it takes for orders to go through and arrive at their destination (i.e., high-frequency trading).

Before RBC acquired this supposed state-of-the-art electronic-trading firm, Katsuyama’s computers worked as he expected them to. Suddenly they didn’t.

It used to be that when his trading screens showed 10,000 shares of Intel offered at $22 a share, it meant that he could buy 10,000 shares of Intel for $22 a share. He had only to push a button.

By late 2007, however, when he pushed the button to complete a trade, the offers would vanish.

He asked the developers to stand behind him and watch while he traded. “I’d say: ‘Watch closely. I am about to buy 100,000 shares of AMD. I am willing to pay $15 a share.

He asked the developers to stand behind him and watch while he traded. “I’d say: ‘Watch closely. I am about to buy 100,000 shares of AMD. I am willing to pay $15 a share.

There are currently 100,000 shares of AMD being offered at $15 a share — 10,000 on BATS, 35,000 on the New York Stock Exchange, 30,000 on Nasdaq and 25,000 on Direct Edge.’ You could see it all on the screens.

We’d all sit there and stare at the screen, and I’d have my finger over the Enter button. I’d count out loud to five. . . .

“ ‘One. . . .

“ ‘Two. . . . See, nothing’s happened.

“ ‘Three. . . . Offers are still there at 15. . . .

“ ‘Four. . . . Still no movement. . . .

“ ‘One. . . .

“ ‘Two. . . . See, nothing’s happened.

“ ‘Three. . . . Offers are still there at 15. . . .

“ ‘Four. . . . Still no movement. . . .

“ ‘Five.’ Then I’d hit the Enter button, and — boom! — all hell would break loose. The offerings would all disappear, and the stock would pop higher.”

At which point he turned to the developers behind him and said: “You see, I’m the event. I am the news.”

At which point he turned to the developers behind him and said: “You see, I’m the event. I am the news.”

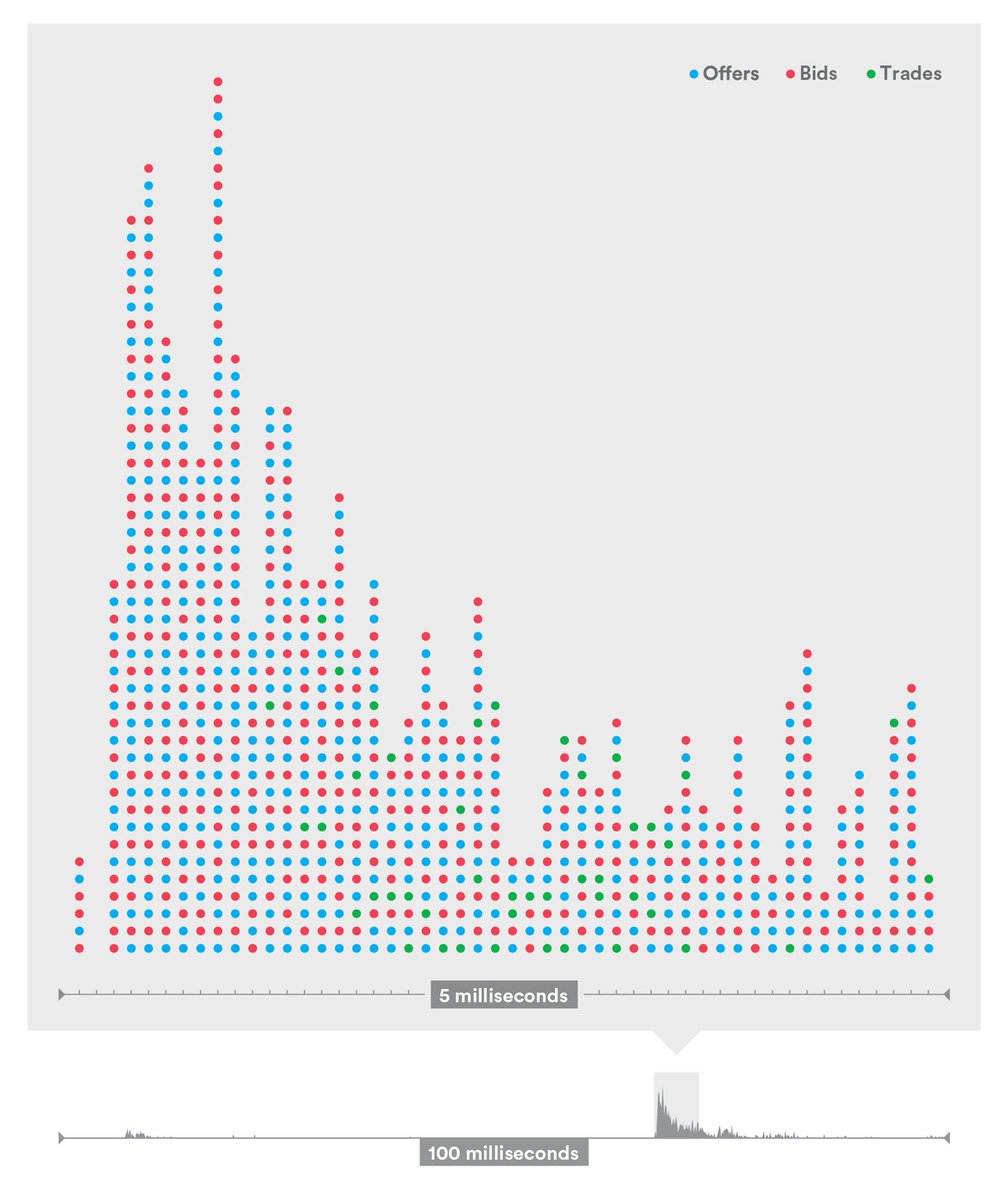

High-frequency-trading activity is not constant; it occurs in microbursts. The gray box magnifies a five-millisecond window, during which GE experienced heavy bid and offer activity and a total of 44 trades.

Graphic: CLEVERºFRANKE. Data source: IEX.

Graphic: CLEVERºFRANKE. Data source: IEX.

In the microseconds it takes a high-frequency trader — depicted in blue — to reach the various stock exchanges housed in these New Jersey towns, the conventional trader’s order, theoretically, makes it only as far as the red line. Graphic: CLEVERºFRANKE. Data source: IEX.

Turns out As of 2010, every American brokerage and all the online brokers effectively auctioned their customers’ stock-market orders. The online broker TD Ameritrade, for example, was paid hundreds of millions of dollars each year to send its orders to a hedge fund called Citadel

For instance, they bought 10 million shares of Citigroup, then trading at roughly $4 per share, and saved $29,000 — or less than 0.1 percent of the total price.

“It was so insidious because you couldn’t see it,” Katsuyama says. “It happens on such a granular level that even if you tried to line it up and figure it out, you wouldn’t be able to do it. People are getting screwed because they can’t imagine a microsecond.”

Broadly speaking, it appeared as if there were two activities that led to a vast amount of unfair trading. The first is electronic front-running — seeing an investor trying to do something in one place and racing ahead of him to the next.

Second is called slow-market arbitrage. This occurred when a high-frequency trader was able to see the price of a stock change on one exchange and pick off orders sitting on other exchanges before those exchanges were able to react.

This is basically why Robinhood is "free".

This is basically why Robinhood is "free".

To Read More:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B00HVJB4VM/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?_encoding=UTF8&btkr=1

https://twitter.com/TheSiskar/status/1354957254202687492 @TheSiskar

Accounts to follow on the subject: @hanstung @hunterwalk @toxic @APompliano

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B00HVJB4VM/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?_encoding=UTF8&btkr=1

https://twitter.com/TheSiskar/status/1354957254202687492 @TheSiskar

Accounts to follow on the subject: @hanstung @hunterwalk @toxic @APompliano

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter