Curious about how we study tiny #chameleons, why we look at their #genitals, and how minuscule #animals can change the way we understand the world?

Here's a T H R E A D

T H R E A D

(1/21)

Here's a

T H R E A D

T H R E A D

(1/21)

You may know #chameleons from the flashy big species that are so charismatic and available in the pet trade, like Furcifer pardalis or Chamaeleo calyptratus. They're famed for their colour change, long prehensile tails, ballistic tongue, bizarre eyes, weird feet. (2/21)

But there are quite a lot of #chameleons that are much smaller, don't have such prehensile tails, and have only limited colour change. There are a few different genera of such 'dwarf' chameleons, but I'll be talking about #Brookesia, one of the genera from #Madagascar (3/21)

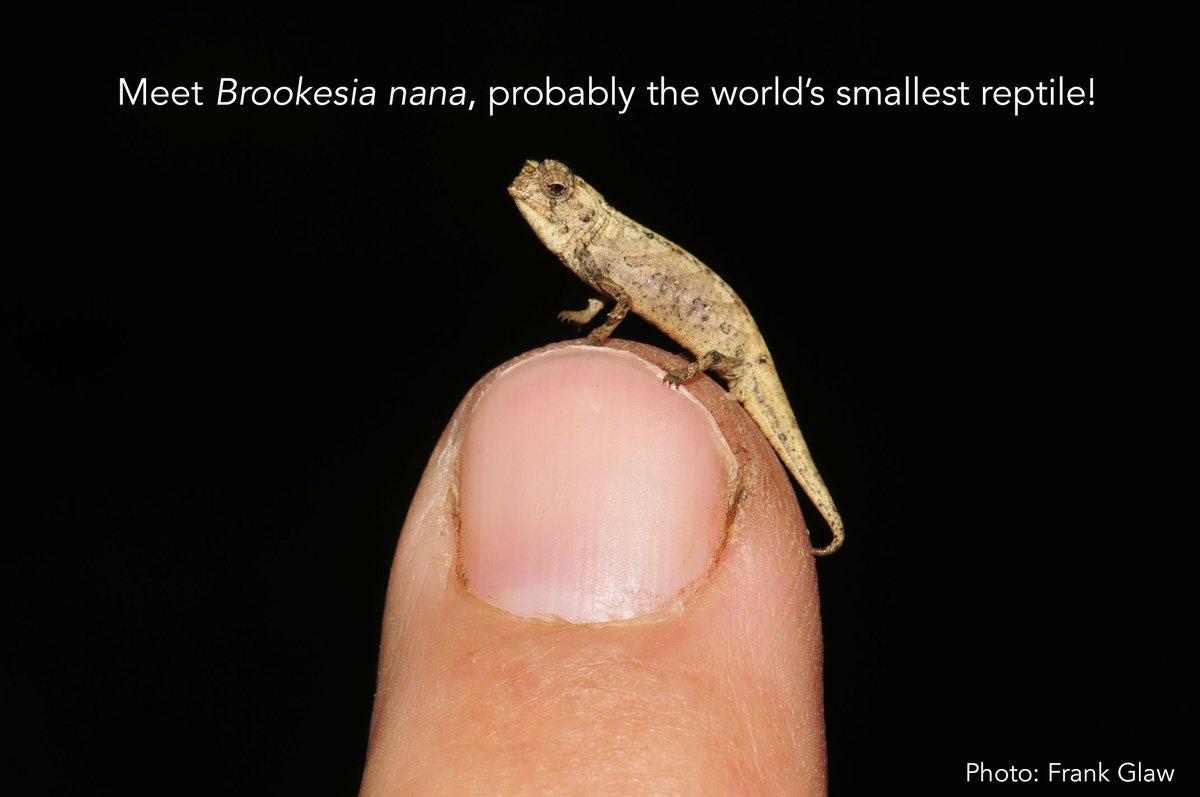

Brookesia range in size from the modestly sized Brookesia perarmata at ~110 mm total length, down to the smallest reptile in the world, Brookesia nana, described today in @SciReports, with an adult male total length of 21.6 mm. (4/21)

https://rdcu.be/cemcW

https://rdcu.be/cemcW

But size variation in Brookesia is not continuous: there is one group of relatively large species, and one group of relatively small ones. In our new paper we revalidated the subgenus Evoluticauda for the clade of 13 extremely small species, like this Brookesia tuberculata (5/21)

Yes, you read that right: as of today there are 13 species of miniaturised chameleons. You may have heard of Brookesia micra, which until today held the title of 'smallest chameleon'—it was described with three other species and much fanfare in 2012 (6/21) https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0031314

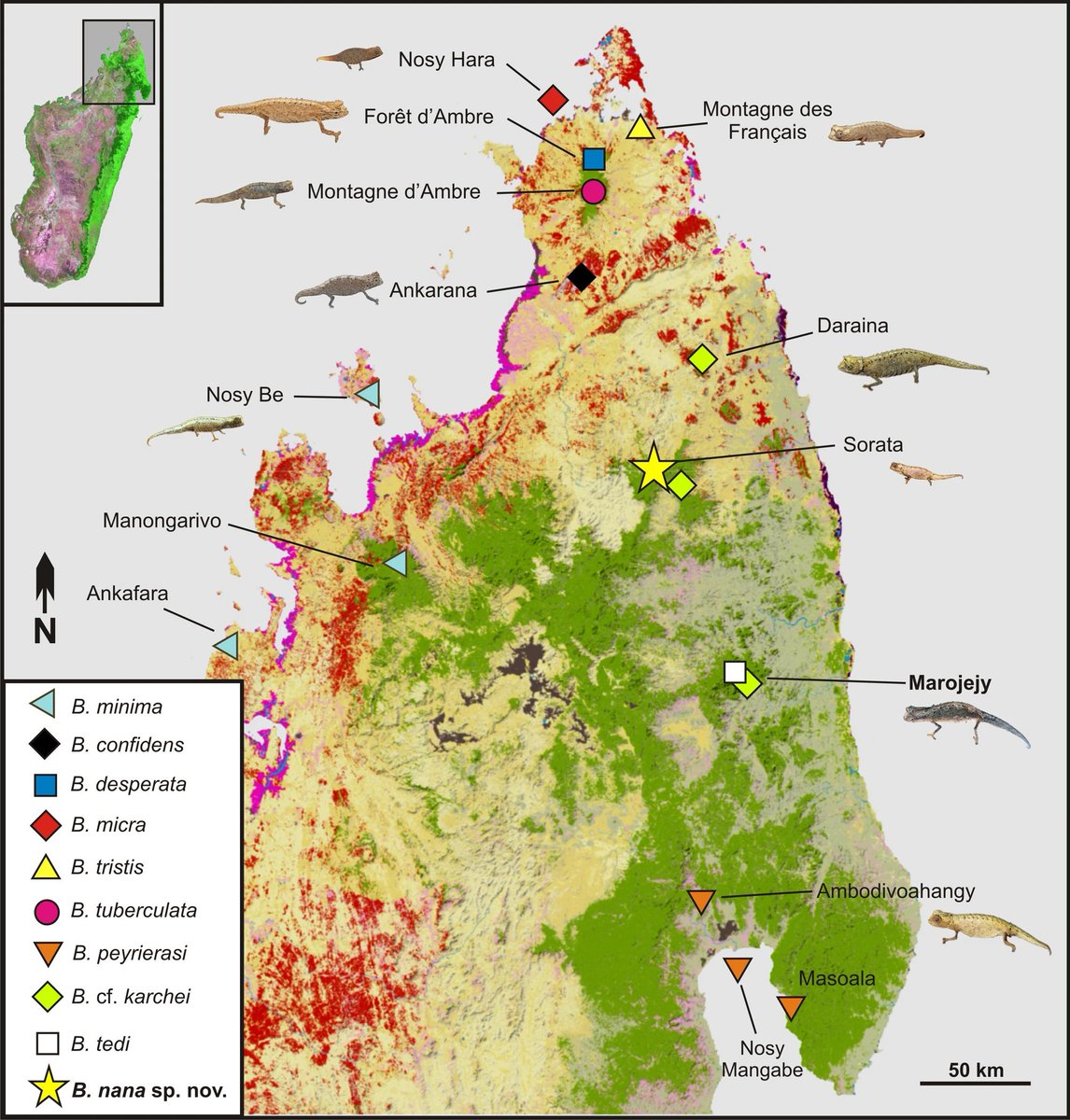

We are slowly piecing together the distribution of this group of tiny chameleons. Unsurprisingly, most are microendemic to tiiiny areas. So, every time we visit a new area, there's a decent chance of finding a new species!

Fig. 3 from our new paper

Fig. 3 from our new paper

(7/21)

Fig. 3 from our new paper

Fig. 3 from our new paper(7/21)

So now to the burning question: how the hell do you even find a tiny chameleon? Well, it takes a lot of practice, and in my experience, you have to be looking specifically for them, because they're damn small and very well hidden both night and day. (8/21)

At night, pretty much all chameleons roost above the ground on some kind of plant. They also reflect torchlight a little, so with good eyes you can spot that (especially large species). Here are a few examples of B. minima and B. tuberculata.

(9/21)

(9/21)

During the day you can more or less forget about finding Evoluticauda. We sometimes employ leaf-litter quadrats, scraping 1 square metre of leaf litter into a bag and then sorting through it slowly, but I wouldn't recommend it.

B. minima from Nosy Be.

B. minima from Nosy Be.

(10/21)

B. minima from Nosy Be.

B. minima from Nosy Be.(10/21)

But the real secret to finding these tiny Brookesia is working with the experts. This man, Angeluc Razafimanantsoa, a guide who works mostly in Montagne d'Ambre National Park in the north of Madagascar, is the absolute master. We hire him to come with on most expeditions (11/21)

Angeluc, and his twin brother Angelun, have been working with members of our team for decades. In 2017 we named a species of frog Stumpffia angeluci after Angeluc, and back in 1995 Chris Raxworthy and Ron Nussbaum named a skink Pseudoacontias angelorum after both brothers

(12/21)

(12/21)

Anyway, once you've found the chameleon comes the question of identifying the species. Well, the fact that most areas have only one species makes this comparatively easy, but if you're somewhere new it's much harder. Here is where the genitals come in. (13/21)

In general, reptile hemipenes (paired ~penises) can often be species-specific in their morphology, meaning that you can use them to identify species. The same is true of beetles and many other arthropods. In the case of chameleons, the structures can be… absolutely crazy (14/21)

But in Evoluticauda, genital morphology stays quite simple, limiting variation mostly to #JustTheTip. This figure from the 2012 paper on Brookesia micra and co shows a bit of that variation.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0031314

(15/21)

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0031314

(15/21)

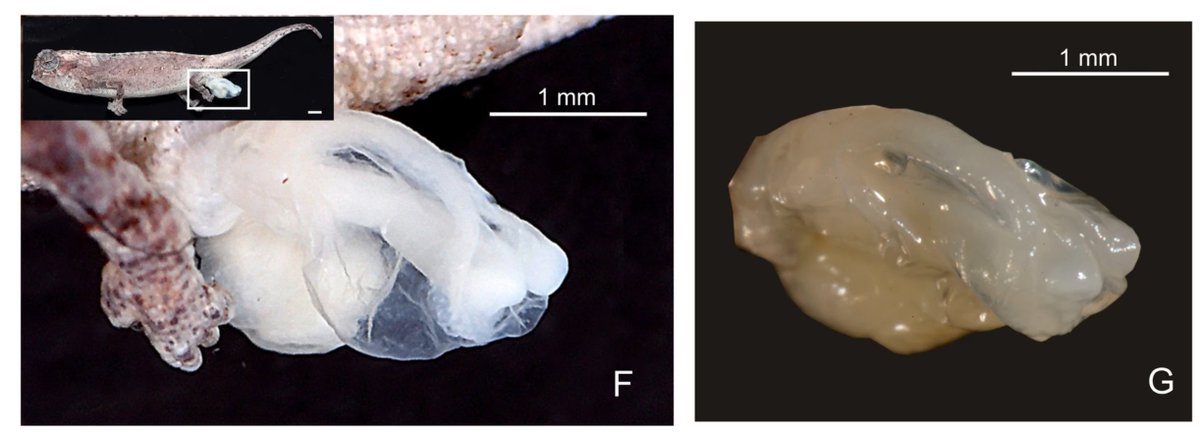

So when we looked at Brookesia nana, the genitals were one of the first things we examined. Sure enough, they are different from all other species. See for yourself if you can spot the differences to the last tweet. (16/21)

from Fig. 5 of our new paper.

from Fig. 5 of our new paper.

from Fig. 5 of our new paper.

from Fig. 5 of our new paper.

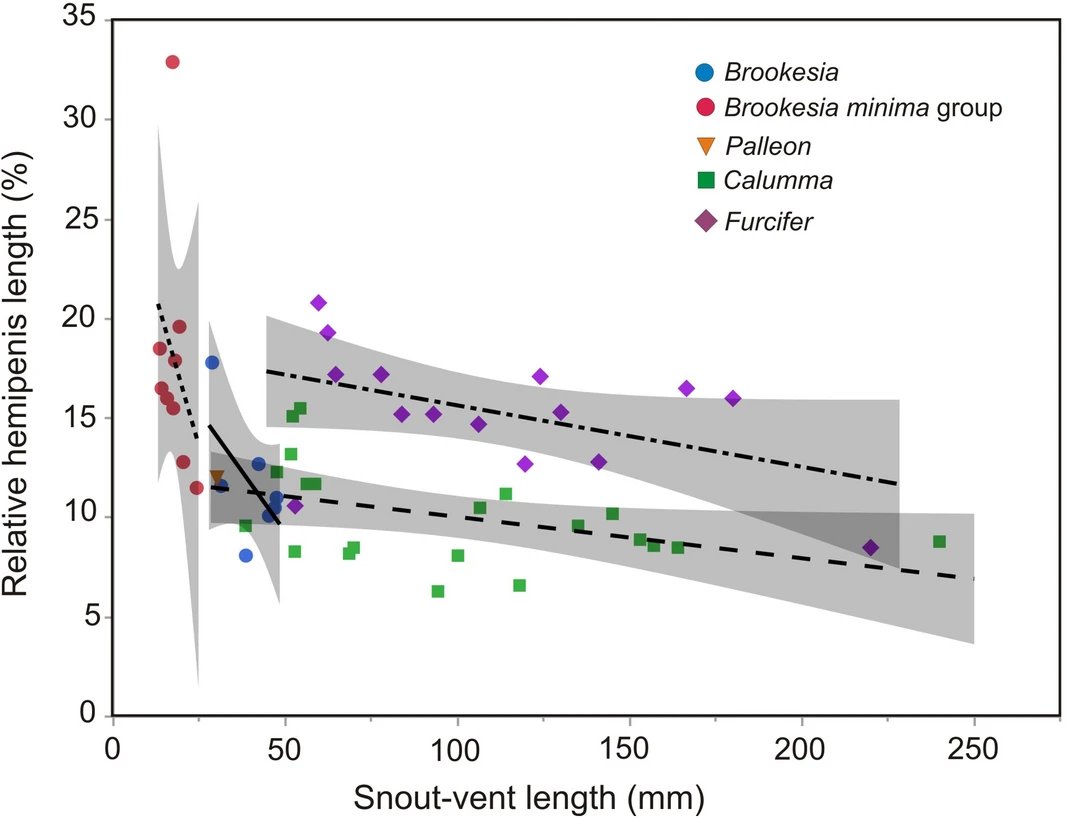

While we were doing this work, we also started to wonder if there is a pattern between body size and genital size, because we knew that B. tuberculata has extremely long hemipenis, and B. nana's seemed quite large as well. The answer: yes! (17/21)

The keen among you will notice that this is not a phylogenetically corrected plot. That is correct and intentional, because (1) multiple individuals of some species are present, and (2) the current chameleon tree is okay, but will be overhauled soon. The trend stands. (18/21)

So why are the hemipenes of these tiny chameleons so long? Well, a great suggestion came from one of our reviewers, and we have worked it into the manuscript. The idea is mechanical coupling: if the male  but female doesn't, his genitals still need to fit hers (19/21)

but female doesn't, his genitals still need to fit hers (19/21)

but female doesn't, his genitals still need to fit hers (19/21)

but female doesn't, his genitals still need to fit hers (19/21)

We know that Brookesia species have substantial sexual size dimorphism, with the males much smaller than females. The male in fact rides around on the female's back until she is ready to mate. So it makes sense that their genitals are limited in ways their bodies aren't (20/21)

By studying these tiny chameleons we have expanded our understanding of how body size relates to distribution, and how constraints work on different parts of the body. It is these kinds of insights that get me so excited to work on the world's smallest vertebrates! (21/21)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter