In the early 2000s, dramatic shifts in radio spectrum allocation for mobile data applications, combined with advances in radio transmission and receiving prompted some networking engineers to propose a radical rethink of radio.

1/

1/

Our current spectrum management assumes that senders and receivers have characteristics that are fixed at the point of manufacture, determined by things like the shape of an antenna and the type of quartz crystal used as an oscillator.

2/

2/

But software-defined radios (SDRs) and software-tunable phased-array antennas make those assumptions obsolete. Today, a radio can be a commodity computer that can sense other devices' RF use and transmit and receive on multiple frequencies to share the airwaves.

3/

3/

This was dubbed "cognitive radio" and its proponents imagined a world where the exclusive spectrum allocations handed out to telcos, broadcasters and other powerful entities would be replaced by a cooperative spectrum model.

4/

4/

Two radios that needed to talk to one another might make contact in one band, switch to another, or ask a third receiver to relay messages for them, using just enough power to reach one another, avoiding the bands that were already in use.

5/

5/

These proposals - which would vastly increase wireless data capacity - were met with fierce resistance, from incumbent licensors, from spectrum speculators, and from HAMs, who are brilliant but also tend to be conservative about spectrum allocation.

6/

6/

These debates inevitably ran up against a hard limit: no one had ever built any kind of serious cognitive radio network. Just trying it would likely trigger massive, brutal FCC enforcement action, as it would trample all that exclusive spectrum.

7/

7/

But that didn't cool the ardor of cognitive radio's fiercest proponents. People like @wa8dzp roamed the world, looking for spectrum havens - places where cognitive radio could be tried. The King of Tonga greenlit one project!

https://www.wired.com/2002/01/hendricks/

8/

https://www.wired.com/2002/01/hendricks/

8/

But the most promising on-shore spectrum laboratories were First Nations territories - sovereign nations whose treaties predated any understanding of electromagnetic spectrum and thus did not cede spectrum rights to settler colonial powers.

9/

9/

Though the legal theory was as untested as the technical one, some First Nations bands dallied with it, wondering if they leverage their position to race past the hidebound rules in the US and Canada to bring money and connectivity to their communities.

10/

10/

I wrote a short story about this in 2002, "Liberation Spectrum," which @Salon published in 2003:

https://www.salon.com/2003/01/16/liberation_spectrum/

11/

https://www.salon.com/2003/01/16/liberation_spectrum/

11/

Making sovereign spectrum policy is one of the better interpretations of treaty law; it has the potential to be as lucrative as, say, casinos - and could also bridge the digital divide for First Nations communities.

12/

12/

Certainly, it's a better idea than the pharma trolls who briefly experimented with transfering patent portfolios to sovereign bands in the hopes of of muddying the jurisdictional questions so that their profiteering would be harder to shut down.

https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2017/09/how-a-native-american-tribe-ended-up-owning-six-key-patents-on-an-eye-drug/

13/

https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2017/09/how-a-native-american-tribe-ended-up-owning-six-key-patents-on-an-eye-drug/

13/

Thankfully, that plan petered out. Likewise, First Nations experiments with spectrum policy seem also to have lost momentum, since then - at least, none have crossed my radar.

Until now.

14/

Until now.

14/

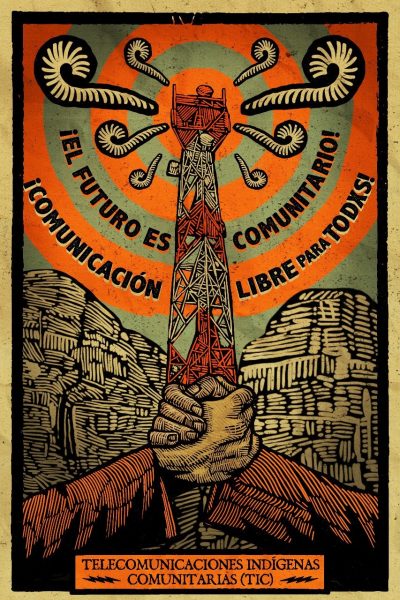

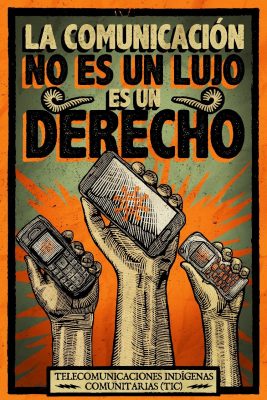

On Jan 13, the Mexican Supreme Court found in favor of Indigenous Community Telecommunications (TIC), unanimously finding that community groups like TIC were entitled to free "social use" spectrum licenses.

https://globalvoices.org/2021/01/27/indigenous-led-telecommunications-organization-wins-historic-legal-battle-in-mexico/

15/

https://globalvoices.org/2021/01/27/indigenous-led-telecommunications-organization-wins-historic-legal-battle-in-mexico/

15/

The decision did not rely on treaty rights, but rather upon a carve out in Mexican spectrum policy that gives free spectrum to community groups. TIC is an incredibly effective network of 80 towns in 18 Indigenous communities operating voice and data mobile networks.

16/

16/

Since 2018, TIC has been under threat, with the regulator demanding 1m pesos for continued access to spectrum; a demand the Supreme Court unanimously voided.

17/

17/

The decision will ease expansions of TIC's service into the vast majority of Indigenous communities that lack reliable mobile service.

http://www.ift.org.mx/sites/default/files/reporte-coberturapueblosindigenas_finalpublicar.pdf

18/

http://www.ift.org.mx/sites/default/files/reporte-coberturapueblosindigenas_finalpublicar.pdf

18/

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter