conservators are an essential part of museum life. They ensure that objects are preserved in as close to original condition as possible for future generations. You rarely see a conservator at work, but you certainly have seen the results of their work. #ConnectingCollections

They advise on storage, and help prevent issues arising (e.g. by monitoring humidity with a sensor like this). They check that objects are stable before they're handled--when someone wants to study it, for example. They also check them before they go on display or travel on loan.

Conservation is painstaking work. The conservators spend countless hours treating objects. For the recent Ashurbanipal exhibition, a team spent thousands of hours making the sculptures look their best.

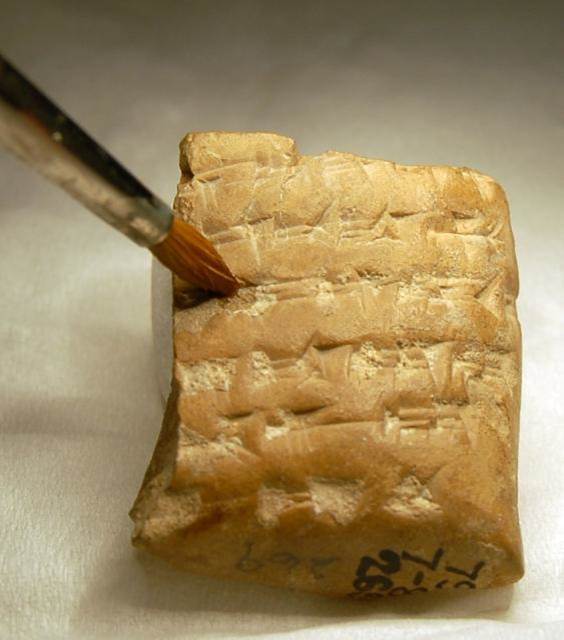

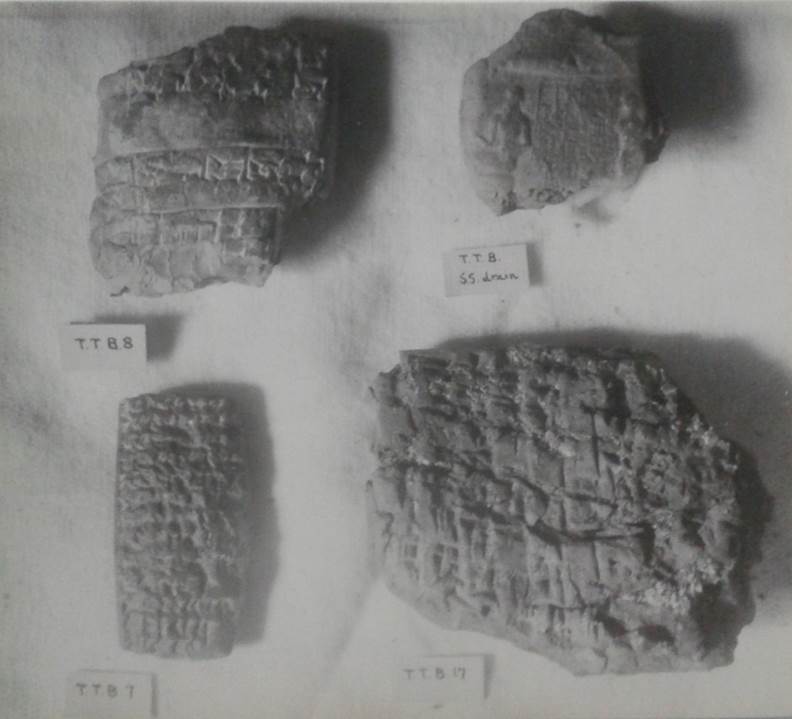

Ceramics conservators clean excavation dirt from the wedges of clay tablets bearing cuneiform inscriptions. Sometimes there are other encrustations. They can be soft or hard. Using a microscope and tools from a small wooden pick to a scalpel, they can clean the surface safely.

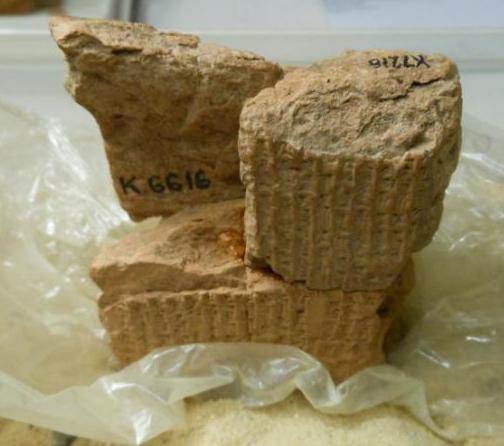

Conservators join fragments of tablets back together. Tablets are often found in broken condition. Curators & visiting scholars work out which pieces belong together. These are then glued. It's like a 3D jigsaw puzzle. Tablets can be reconstructed from many separate fragments.

Sometimes a "support fill" is needed to make the newly joined fragments stable. Small fills use a paste of micro-balloons and a special glue.

Larger supports can be created from plaster and then attached. The tablet is protected with a barrier material to prevent migration of water.

If needed, tablets can be consolidated (strengthened) with an adhesive, applied with a micro-pipette, under magnification.

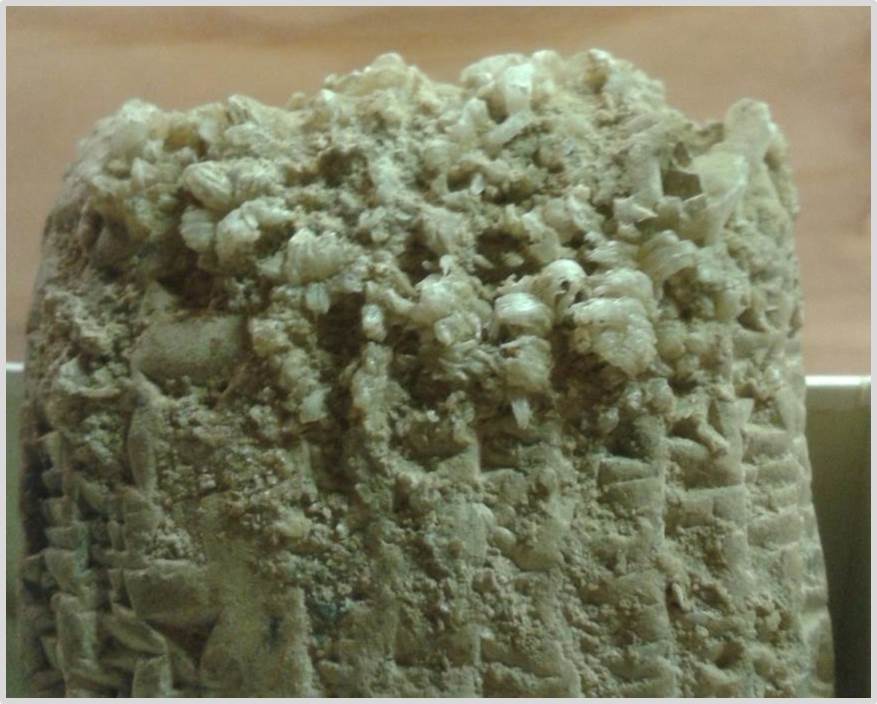

Tablets are difficult to conserve. Different approaches have been taken around the world. The basic problem is salts crystallising, pushing the surface from the tablet. Salts come from the clay of the tablet, but can combine with gasses from wooden storage to form new salts.

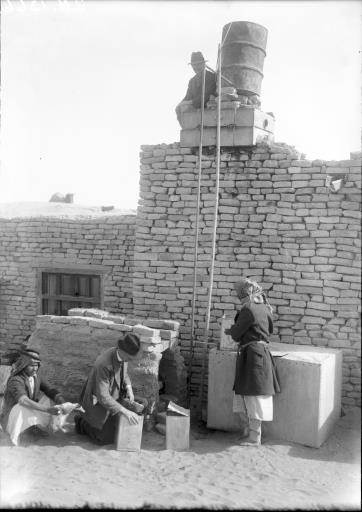

Over 100 years ago, it was discovered that firing tablets could help stabilise them. Once fired, the tablets could be soaked in water to remove the salts. Sometimes this firing was done on excavation (seen here at Ur, 1920s), at other times it was done in museums.

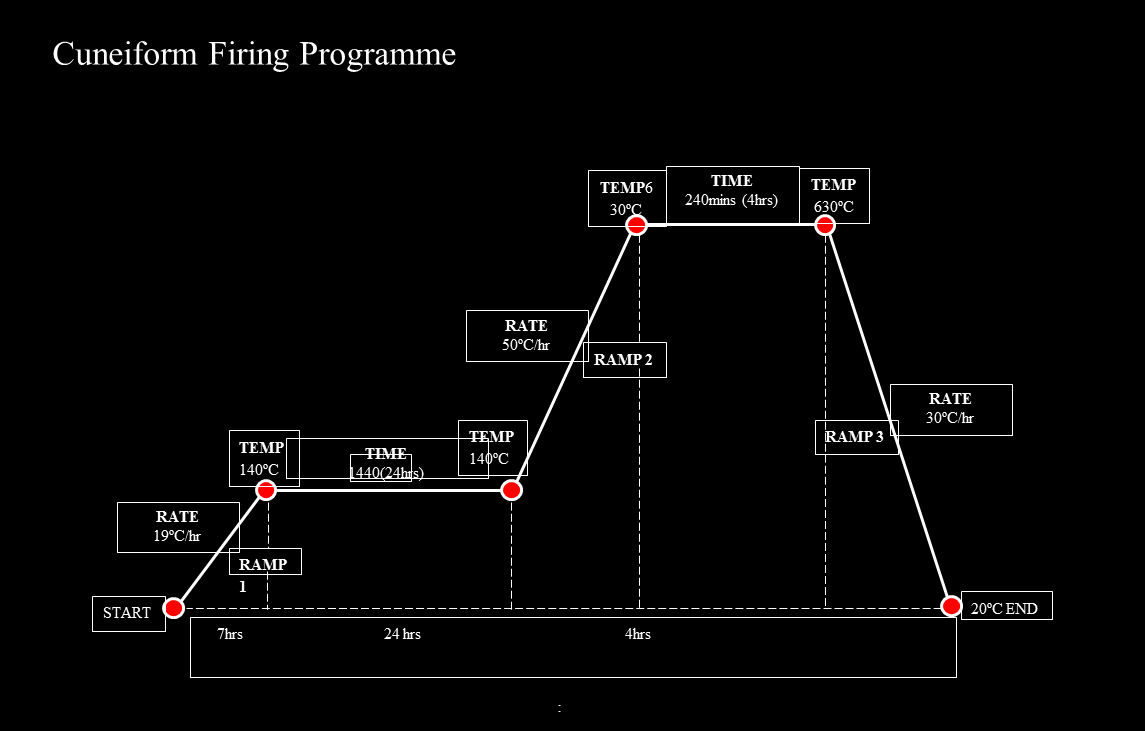

Nowadays, it's rare to fire a tablet. To avoid damage, you need to control the temperature carefully, raise & lower it slowly, and set it at the right level for the right length of time. If the problem salts are not water soluble, firing won't help. Tablets still need monitoring.

Firing is a major intervention, and is not reversible. It changes the nature of the material. And it can remove all sorts of information. For example, organic materials--such as plant and shell remains, as well as inks--will be burnt off.

Tablets from the same ancient archive behave differently in different collections around the world, depending on local conditions, storage and treatment. Conservators document their work carefully, & share their experience and knowledge, helping each other find the best solutions

Conservation is an active field, with new treatment methods being found. Here's a paper on a new treatment method for cleaning naturally deposited dirt from sculptures. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6412/10/11/1099/htm

Conservators can also be active on excavations. Here's Duygu Çamurcuoğlu working at Çatalhöyük in Turkey. You can read more about her and her work here: https://duygucamurcuoglu.com/cv/

If you'd like to hear more about what conservators do and how they do it, you might like this podcast interviewing Carmen Gütschow. http://www.wedgepod.org/episode-list/

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter