A counterpoint to the alarm bells that are sounding over novel SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Is it possible that we are misinterpreting differences in human behavior as differences in the biological fitness of viral variants?

A thread to explain this hypothesis...

Is it possible that we are misinterpreting differences in human behavior as differences in the biological fitness of viral variants?

A thread to explain this hypothesis...

1. Infectious disease transmission is heterogeneous (overdispersed), largely due to human behavior.

Large "superspreading events", differences in behavior, and/or people who have many contacts generate an outsized number of transmission events.

Large "superspreading events", differences in behavior, and/or people who have many contacts generate an outsized number of transmission events.

2. This makes it easy for viral variants - even those with no inherent transmission advantage - to take over a population.

Imagine an infected person attending a large indoor gathering with hundreds of people. That viral strain will expand - because of behavior, not biology.

Imagine an infected person attending a large indoor gathering with hundreds of people. That viral strain will expand - because of behavior, not biology.

3. If we look for viral variants that are expanding in the population, and transmission is (behaviorally) heterogeneous, we will find certain variants that take over - even if those variants are not biologically more transmissible.

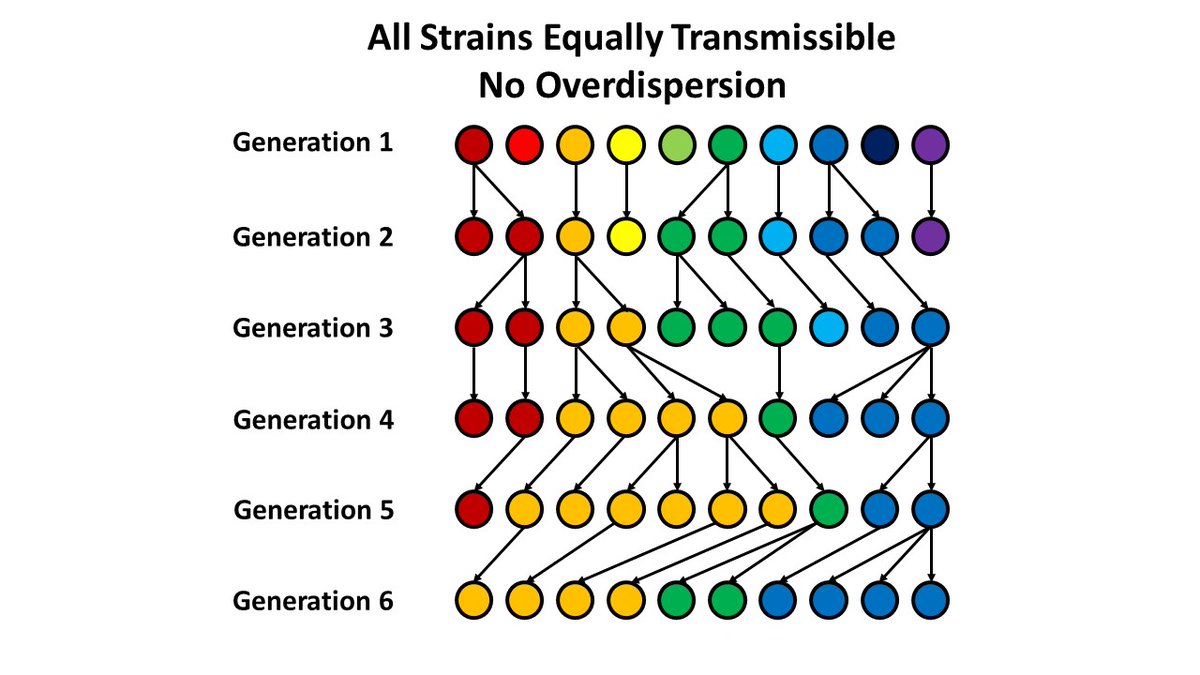

4. An example (based on a random number generator): Assume you have 10 people infected with 10 different strains. On average, each person infects one other person (R=1). If each transmission event is random (Poisson distributed), no one variant tends to take over.

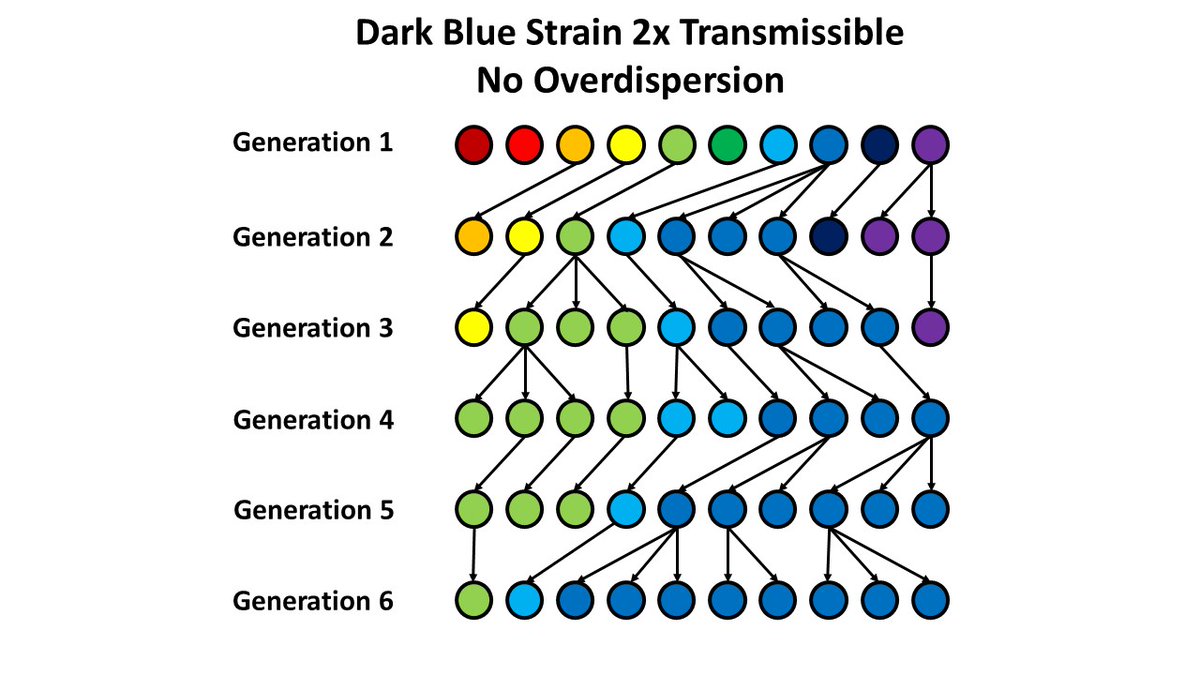

5. Now, consider a biologically more transmissible variant. Not surprisingly, this strain will take over the population - as we saw with the B.1.1.7 variant in England, for example.

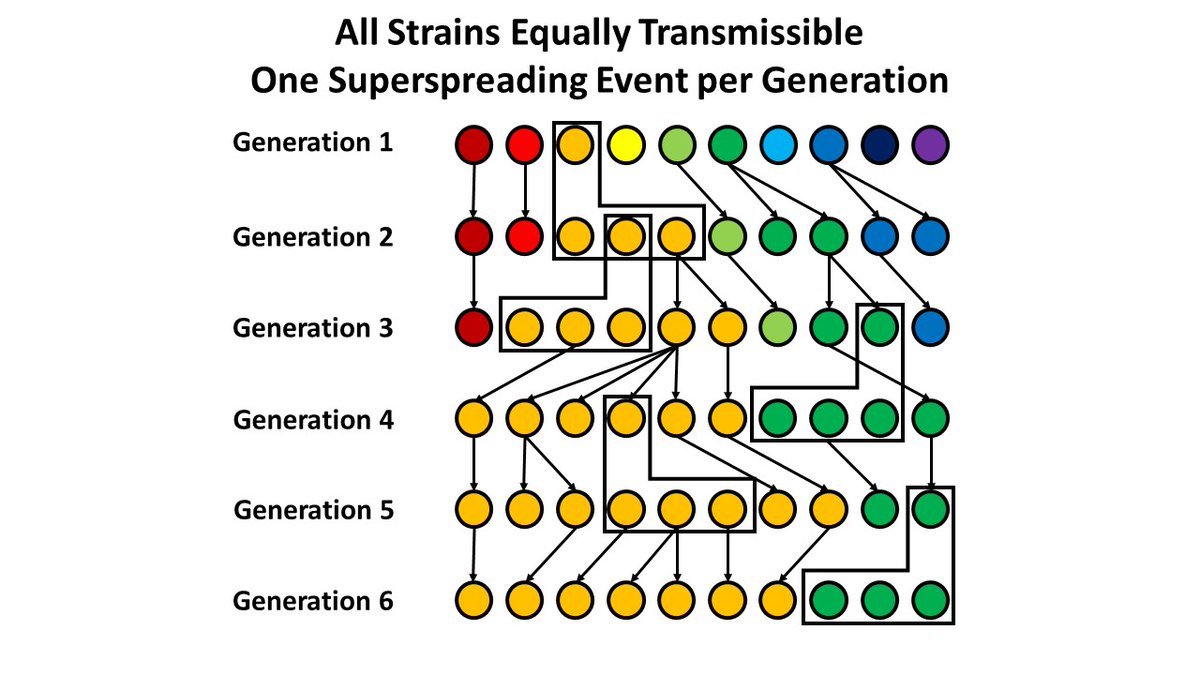

6. But, now consider transmission with "superspreader" events. What happens in this system looks very similar to the more transmissible strain above - it's just that one (orange) variant gets "lucky" to be involved in those events more than other variants.

7. So, if you just look retrospectively, it's impossible to tell the difference between a "fit" variant and a "lucky" one - and easy to interpret the "lucky" strain as being more biologically transmissible.

8. Additional evidence has been cited for the transmissibility of B.1.1.7. First, this variant has mutations that increase transmissibility in the lab. I agree, but would argue we as scientists should be humble & skeptical - we have a strong bias toward finding such evidence.

9. It's also true that the areas of England where the variant first took over also saw more rapid increases in case counts.

But this would be true whether the underlying mechanism was increased transmissibility of the virus, or more frequent superspreading events.

But this would be true whether the underlying mechanism was increased transmissibility of the virus, or more frequent superspreading events.

10. Also, contacts of people with B.1.1.7 were more likely to be infected than contacts of people w other variants.

But superspreading events (or people taking fewer precautions) would also be expected to affect contacts - again without having to invoke higher transmissibility.

But superspreading events (or people taking fewer precautions) would also be expected to affect contacts - again without having to invoke higher transmissibility.

11. The best way to evaluate increased transmissibility is to *prospectively* determine whether incidence continues to increase in areas with these new variants (or can take over new populations) - *after* the variant has been identified. "Lucky" strains won't persist forever.

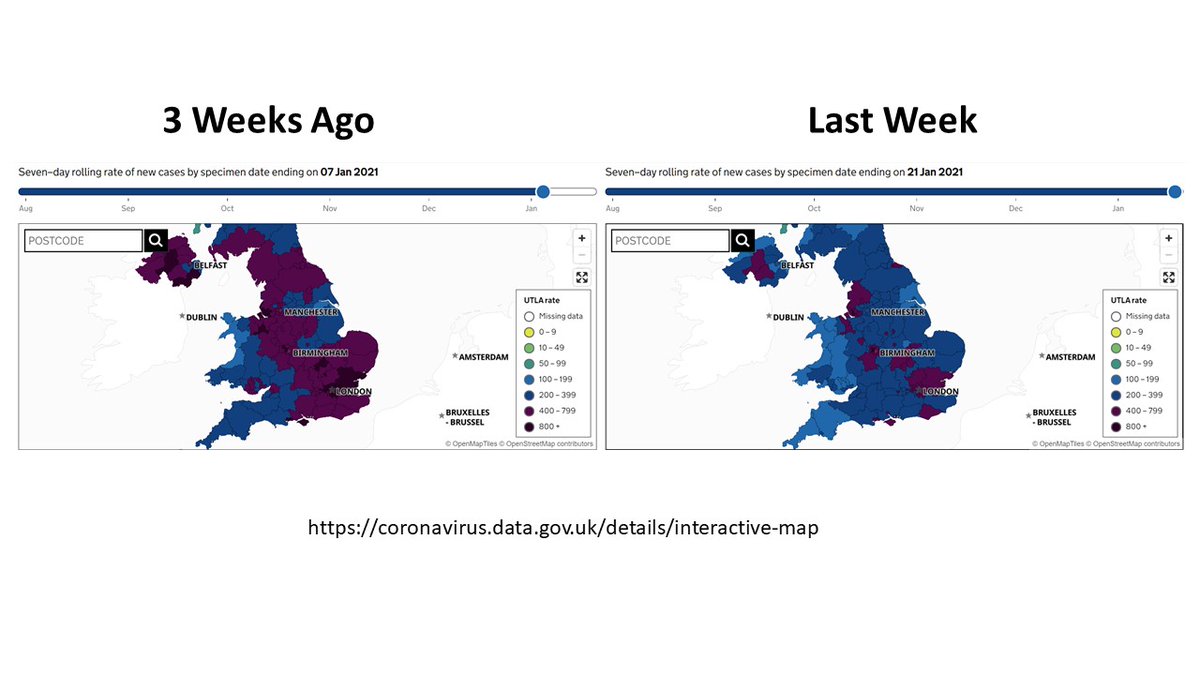

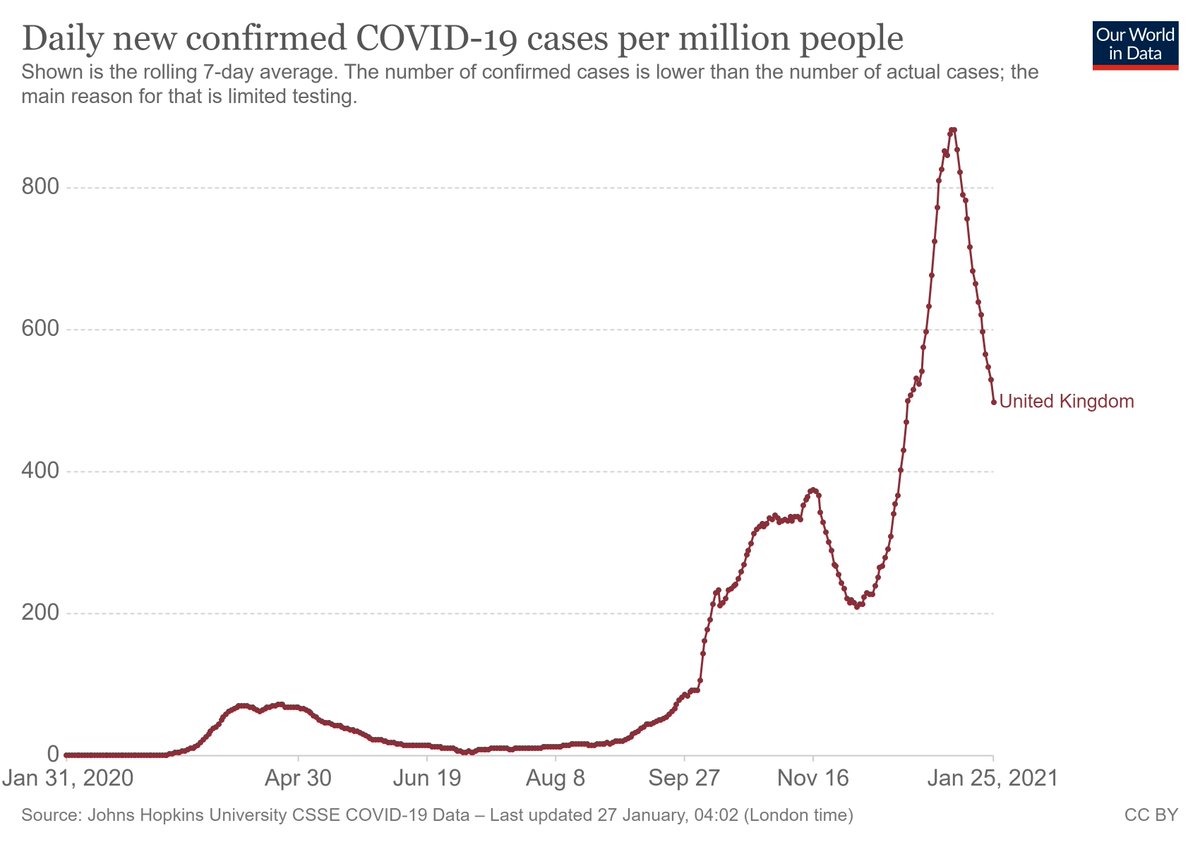

12. So, what is happening in England now? I'll let the maps below speak for themselves - cases per 100,000 population in the week of Jan 7 (~2 generation times after the variant was first widely publicized) and the week of Jan 21 (2 weeks later).

13. It's true that this also reflects a strict lockdown in England - but worth noting that this decline was much more rapid than in March. Herd immunity tends not to generate rapid drops in incidence - and hard to believe this could be achieved if R0 had gone up 50% with B.1.1.7

14. It's also true that B.1.1.7 has been detected in many other countries - but despite this variant being in circulation since Sept., there's no evidence that it has taken over any other large-sized population. Again, difficult to square with a 50% increase in R0.

15. All this to say, the most parsimonious explanation for the rise of variants like B.1.1.7 might be simple overdispersion and human behavior, not increased viral transmissibility. It's not a scientifically sexy explanation, but imho one worth considering more carefully.

(16. And can we please stop calling these the "UK variant", "South African variant", etc? Countries should not be penalized/stigmatized for conducting good surveillance...it creates a strong incentive not to collect these data...)

(17. Also, I would argue that we need to check our own cognitive [political?] biases - arguments that augment the the pandemic are generally better received by scientists than arguments that we may be overstating the problem. This can have negative consequences.)

Sorry for a long thread.

Long story short, it's critical to study these new variants - and in general wise to proceed with caution.

But we also need to take care with concepts that can stoke panic, when cases are falling & the public may perceive scientists as biased.

Long story short, it's critical to study these new variants - and in general wise to proceed with caution.

But we also need to take care with concepts that can stoke panic, when cases are falling & the public may perceive scientists as biased.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter