In the run up to the #Perseverance landing, we will be tweeting about some of the earlier missions to Mars to show the rollercoaster of emotions that the people involved will - as they always have done - have gone through.... So with no further ado..... Mariner 4

The Red Planet was always a difficult object to observe from Earth. It is a small object, even when passing close to us and the Martian surface had little inherent colour and variation apart from dustiness @howellspace @Thievesbook @tanyaofmars @robert_zubrin @timmermansr

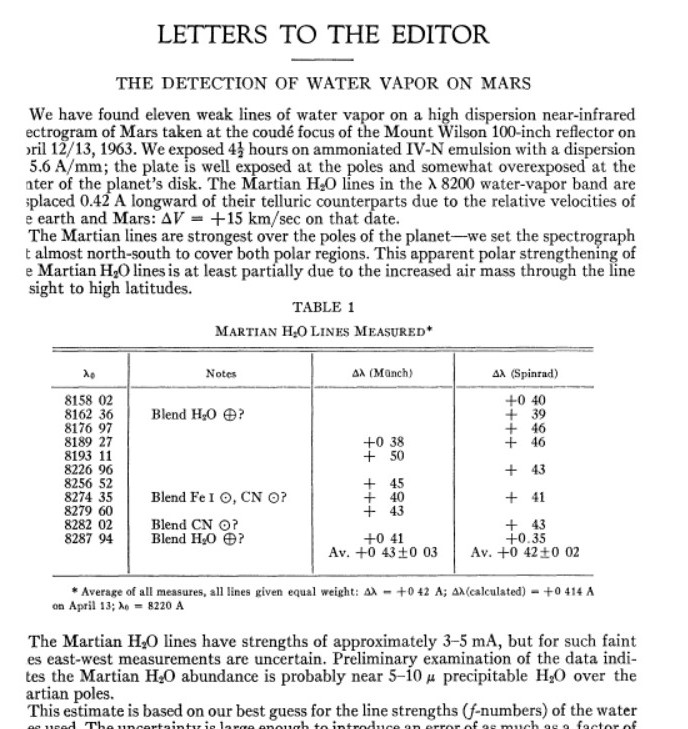

A case in point was water. As late as the spring of 1963, Spinrad, Neuagbauer and Munch found the first spectral lines for water vapour. That was the good news. The bad news it also implied that the atmosphere was very, very thin. https://www.caltech.edu/about/news/50-years-ago-first-look-dry-mars-42694

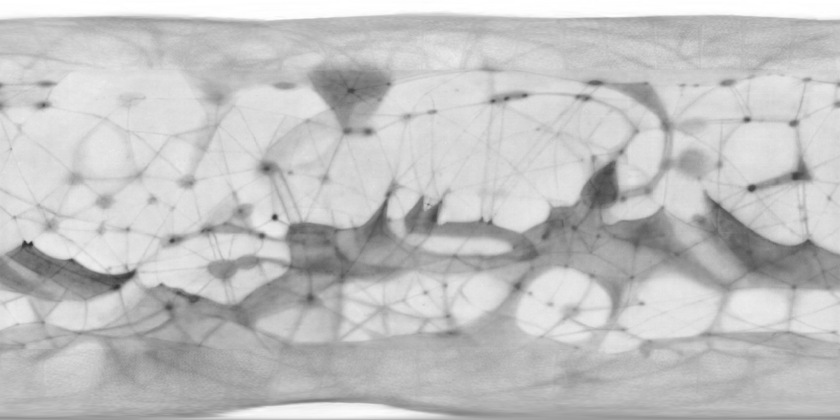

The irony is that Percival Lowell had mapped whole canals across the surface. As late as 1964, the official U.S. Air Force Cartography Centre map of Mars was still covered in.... canals

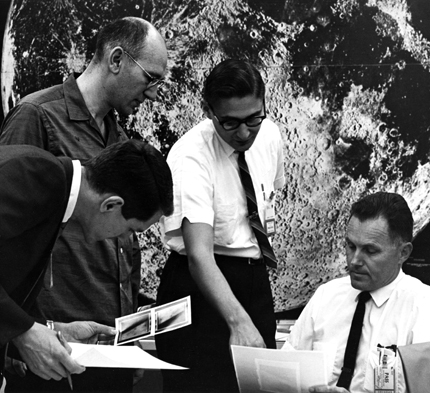

In July 1964, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory sent the first successful mission to the Moon, Ranger 7 – after six straight failures - and prepared to fire the first Mariners towards Mars (shown here as they celebrated) @MoonToMarsQuest

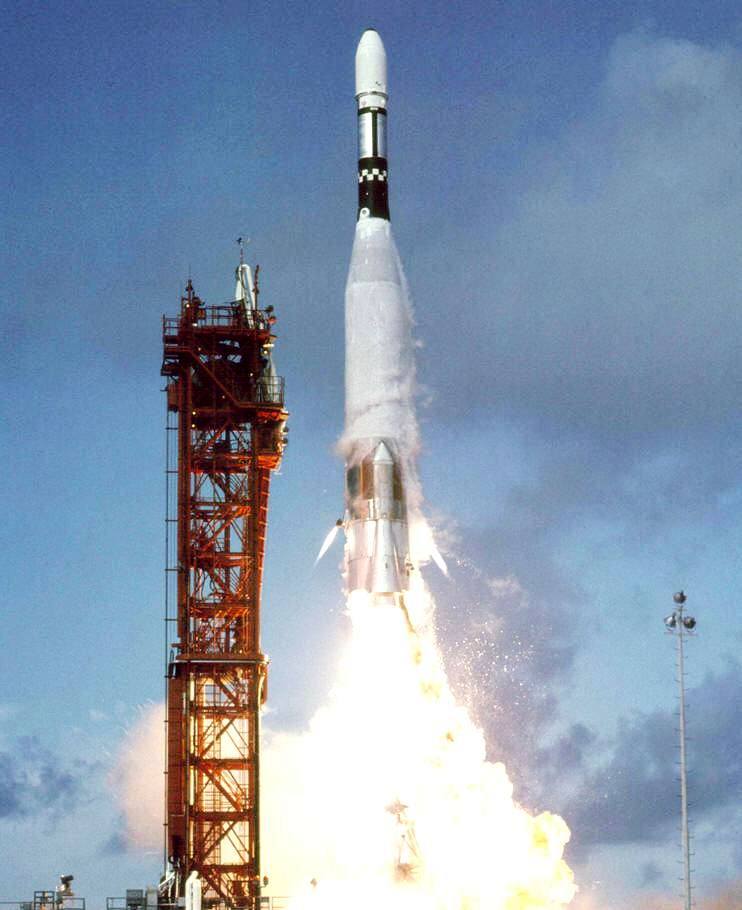

On November 5th, 1964 the fairing on the Agena upper stage failed to deploy as it collapsed – so Mariner 3 was stuck “Like a butterfly in a cocoon” in the words of one JPLer

The Lockheed and JPL teams had three weeks to re-design the shroud – which they did, and thankfully it worked. Mariner 4 lifted off successfully .....and then its own problems began

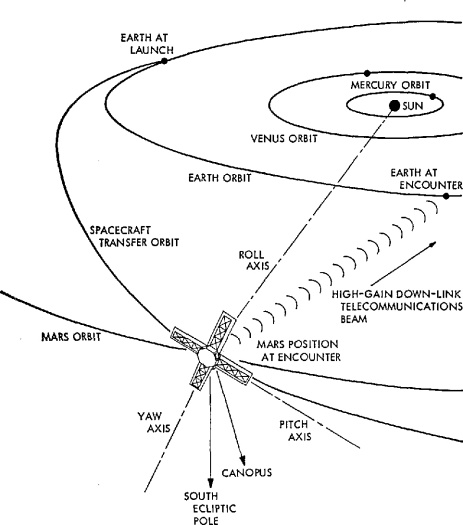

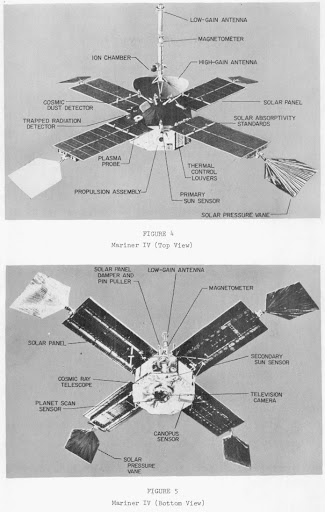

As with their nautical namesakes, the Mariners navigated by the stars – in this case, using the Sun and Canopus, a bright star seen to best advantage from the southern hemisphere (and in the apt constellation of Vela, the sail!)

Within minutes, Mariner 4 was going "crackers". Its Canopus tracker was wandering all over the sky. At the Cape, the JPL flight team wondered what on Earth was going wrong. Paint flakes. In the vacuum of space, paint from the Agena upper stage had flaked off reflecting sunlight

A week later, just before its first "mid course correction", Mariner 4 lost Canopus again. With minutes to spare, controller re-orientated it. And then it lost Canopus again

Worse, ground-based radio telescopes started to see some inexplicable high-energy bursts from where Mars was in the sky. If they were Martian, it was obvious Mariner 4 was not hardened against such bursts

Thankfully, the bursts were from "behind" the planet and stayed put as Mars moved along its orbit. But then in early 1965, Mariner 4's solar wind detector went haywire and switched itself off.

How do you build a spacecraft with sixties technology to reach another planet? That was exactly the problem that JPL engineers Jack James and Dan Schneiderman had in 1962 when they began “Mariner Mars 1964”

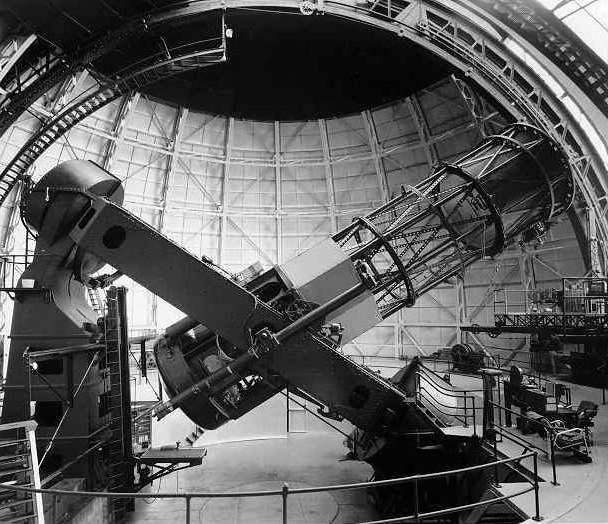

Computers were rudimentary. Many commands had to be sent up from earth. To do that required improved radio telescopes so a dedicated “Mars station” at Goldstone was enhanced for that very purpose

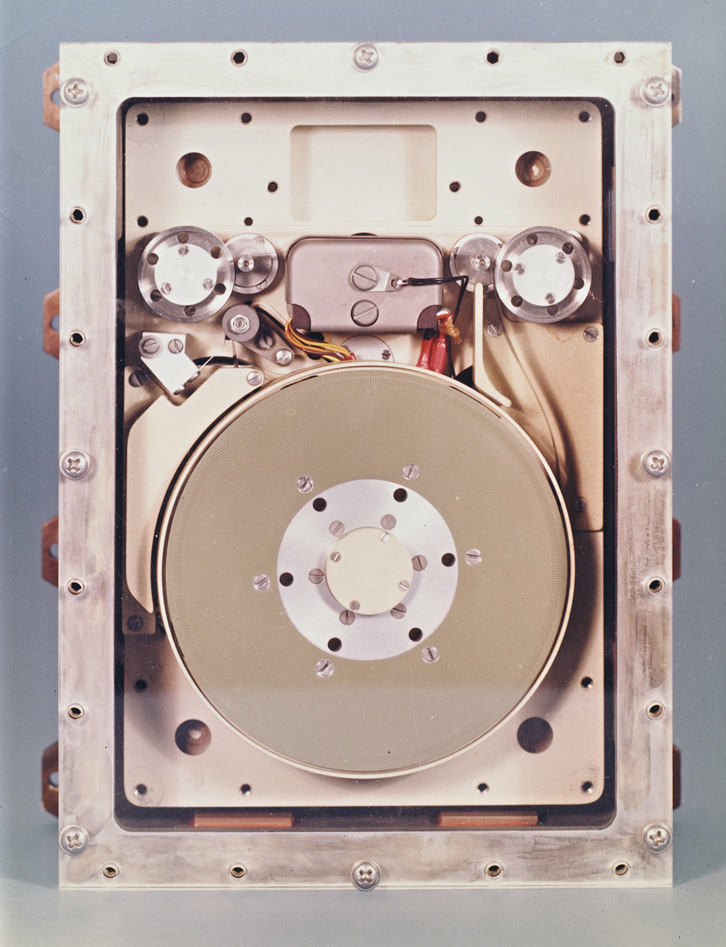

And to store data and marshall the telemetry back and to, high tech in 1964 was the tape recorder flown aboard Mariner 4 itself. Many of the commands to switch on and record data were sent from Earth.

The full, rollercoaster ride was recorded by film cameras behind the scenes at JPL It shows the full gamut of emotions that anyone flying a mission to Mars would - then and now - undergo.

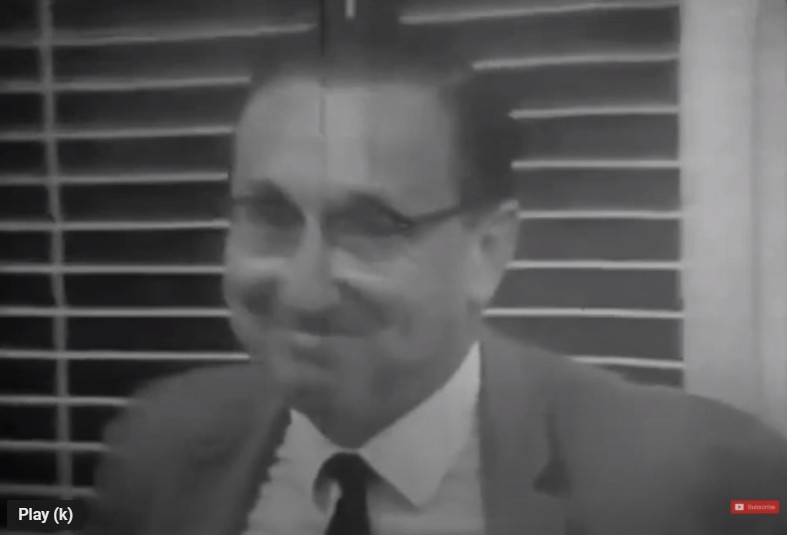

The public wanted to see Mars in close-up. To build the first lightweight digital TV camera capable of taking photographs they turned to a phenomenal instrument builder at Caltech: Professor Robert Leighton (Caltech photo, bottom right)

The Mariner 4 TV camera team - shown here with the Friedan calculators in the foreround - included Bob Sharp, another Caltech professor, whose name lives on at the landing site for the Curiosity lander which the rover is driving up today

And then on Bastille Day 1965, Mariner 4 encountered. Would it work? There was no way of knowing and at first it seemed set fair. The spacecraft was working well.

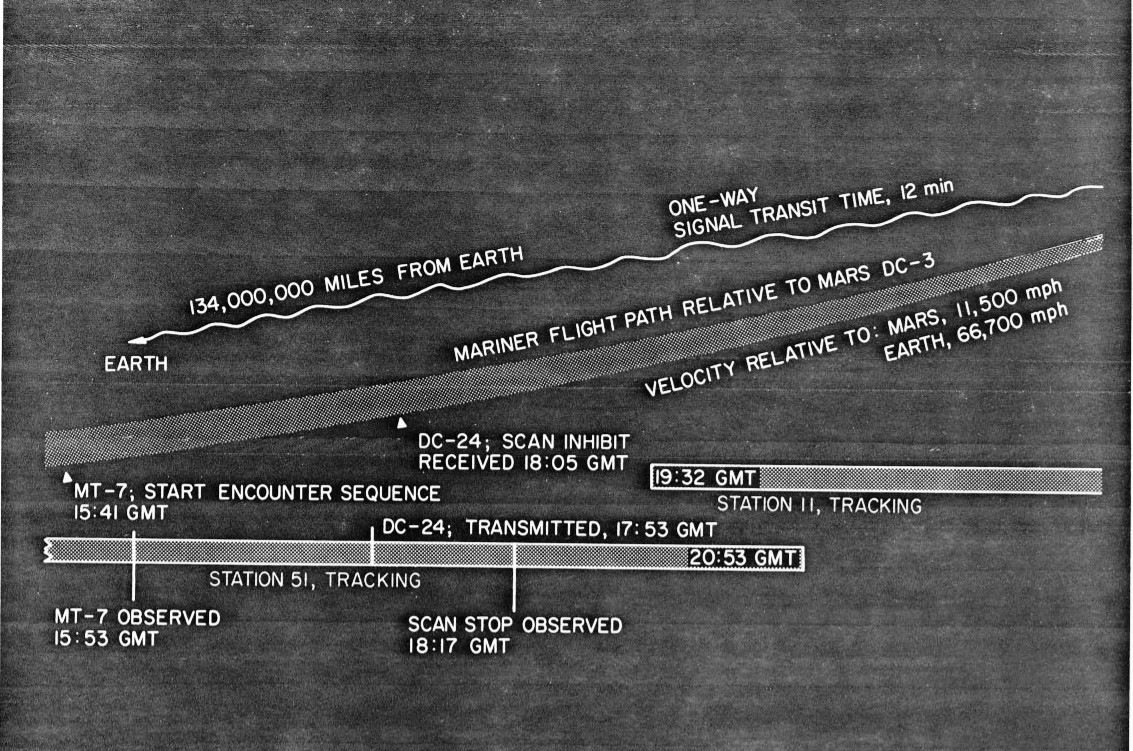

July 14th 1965. It took about twelve minutes on encounter day for a signal to reach Mars. Add another twelve for the return confirmation. Patience has always been a virtue anybody wanting to explore the Red Planet has needed.

As the behind the scenes footage shows, there was a horrible moment when it looked like one command had been received but the next, not. Had the tape recorder spool not been commanded off? The precious data would literally have been taped over as the spool wound on.

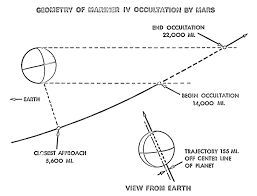

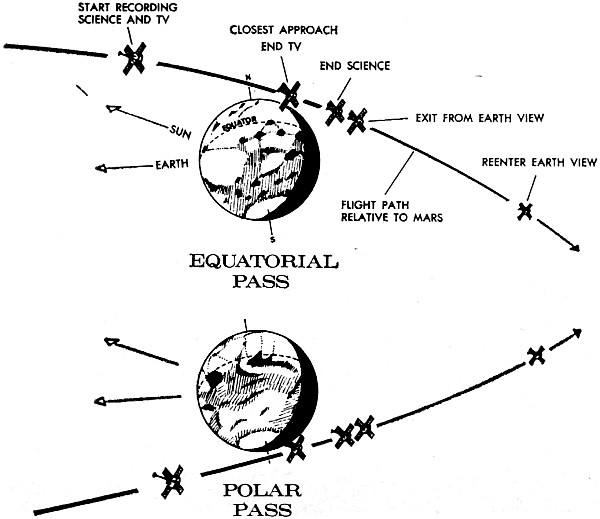

But it hadn’t. The command had arrived. As can be seen in these stills, the scientists and engineers had prevailed. Twenty-two precious images were recorded as Mariner 4 flew high over the southern hemisphere before passing behind the Red Planet as seen from Earth

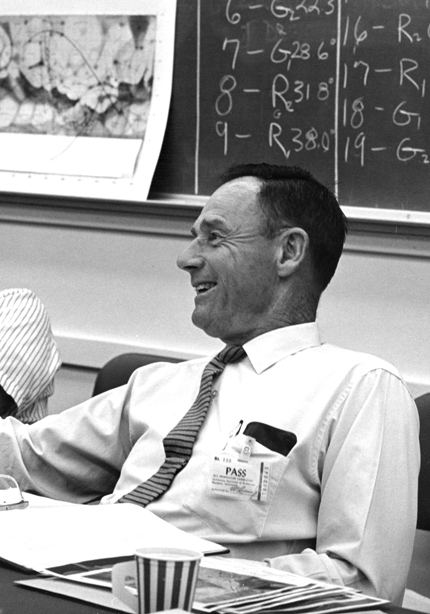

Even the recalcitrant solar wind instrument switched itself back on in time for the fly-by and the guy puffing happily on his pipe was James Van Allen, who had worked with JPL – and its director, Bill Pickering – for many years

Then the media clamour began. Where were the pictures? Mariner 4 could only transmit at 8 bits per second; each frame was made up of 10,000 bits of information.

All the camera data would take another ten days to transmit back to Earth. The press got a shade impatient: so some JPLers took the actual data – the print outs of ones and zeroes - and coloured them in. There were 256 levels of light which could be shaded in using crayons

As the late Jurrie van der Woude, a legend in the photolab at JPL (and later in public information) said: what they produced was as precious as a Rembrandt (he was born in the Dutch East Indies). And it’s still there in the basement of Building 180 at JPL. @GabriellBirchak

Early on in the mission planning, Dan Schneiderman realised they could pull another rabbit out of a hat. If Mariner 4 passed behind Mars it would emerge from the other side – and as it did so, its radio signals would pass through the atmosphere, revealing clues to its structure

And for that he turned to a remarkable JPL engineer called Arvydas Kliore –

https://dps.aas.org/news/arvydas-j.-kliore-1935-2014

- who worked out how to do exactly that. The Martian atmosphere was very very thin, less than 10 millibars (the same on Earth at 100,000 feet).

https://dps.aas.org/news/arvydas-j.-kliore-1935-2014

- who worked out how to do exactly that. The Martian atmosphere was very very thin, less than 10 millibars (the same on Earth at 100,000 feet).

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter