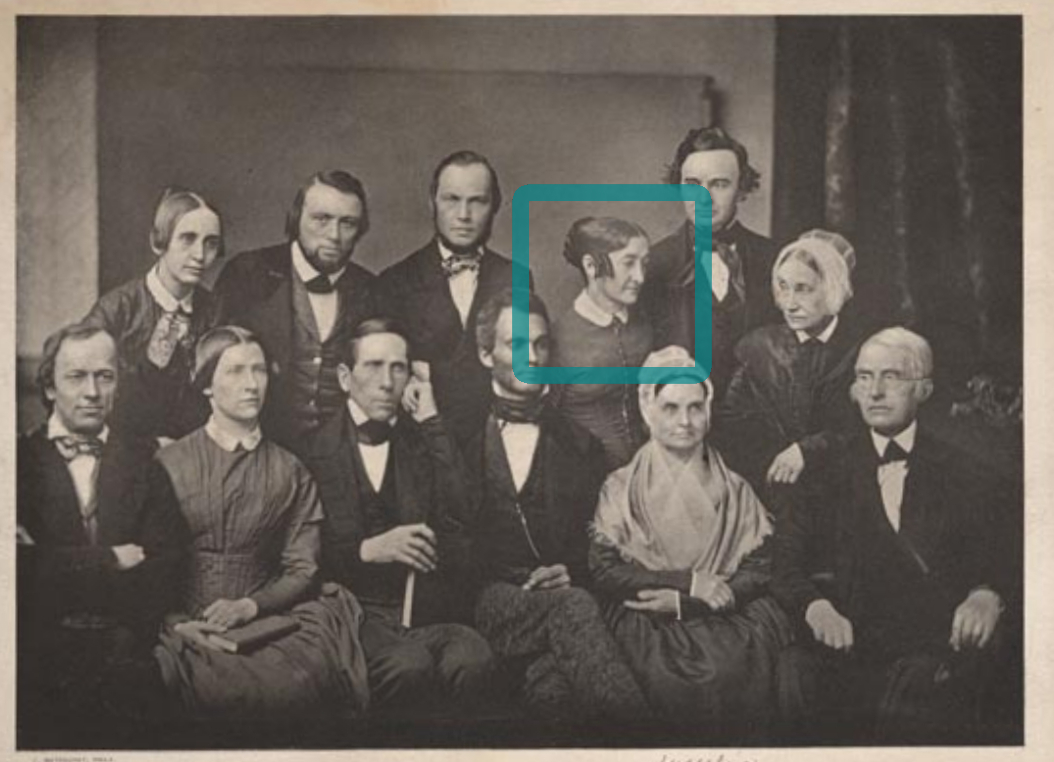

This is the Pennsylvania AntiSlavery Society in 1851.

You might recognize Lucretia Mott, front row in the bonnet, between her husband James and Robert Purvis.

But who are the other women? And why is this building on fire?

Long thread.

You might recognize Lucretia Mott, front row in the bonnet, between her husband James and Robert Purvis.

But who are the other women? And why is this building on fire?

Long thread.

The four other women in this picture had politics as radical as Lucretia Mott’s — and their personal lives were even more unusual.

Today, meet Sarah Pugh.

Sarah Pugh was 35 years old when she heard British abolitionist George Thompson speak and was converted to the cause.

Today, meet Sarah Pugh.

Sarah Pugh was 35 years old when she heard British abolitionist George Thompson speak and was converted to the cause.

Until then she had spent her life teaching; by 1829 she ran a Quaker school with two close friends, Rachel Peirce and Sarah Lewis.

Lewis joined her in the cause and they soon devoted themselves to running the newly-formed Philadelphia Female AntiSlavery Society.

Lewis joined her in the cause and they soon devoted themselves to running the newly-formed Philadelphia Female AntiSlavery Society.

In 1837 Pugh traveled to New York City for the first American Women’s AntiSlavery Convention. The next year she didn't sail for New York—that’s right, sail—as Philadelphia would host the convention.

It was to be held at the brand new Pennsylvania Hall, built by the community.

It was to be held at the brand new Pennsylvania Hall, built by the community.

They needed to build a building.

You see, no one in town would rent abolitionists space to meet.

So white abolitionists & free people of color bought $20 shares—2,000 shares in all—and built their own building.

It had a lecture hall, meeting rooms, galleries, a bookstore.

You see, no one in town would rent abolitionists space to meet.

So white abolitionists & free people of color bought $20 shares—2,000 shares in all—and built their own building.

It had a lecture hall, meeting rooms, galleries, a bookstore.

The building lasted four days.

Its first big event was the second annual American Women’s AntiSlavery Convention.

As the women spoke, a mob surrounded the building and threw rocks at the windows.

Later that night, a huge crowd overran the building and set it on fire.

Its first big event was the second annual American Women’s AntiSlavery Convention.

As the women spoke, a mob surrounded the building and threw rocks at the windows.

Later that night, a huge crowd overran the building and set it on fire.

What upset them?

Black and white women and men mingling, and women speaking in front of an integrated, male audience.

Especially the mixed seating, and that Black and white attendees had exited the hall arm-in-arm. (Otherwise the Black attendees would have been lynched.)

Black and white women and men mingling, and women speaking in front of an integrated, male audience.

Especially the mixed seating, and that Black and white attendees had exited the hall arm-in-arm. (Otherwise the Black attendees would have been lynched.)

The fire department didn’t try to save the building, which was damaged beyond repair.

In the investigation that followed, the city blamed the abolitionists.

They had inflamed the mob by “advocating doctrines repulsive to the moral sense of a large majority of our community.”

In the investigation that followed, the city blamed the abolitionists.

They had inflamed the mob by “advocating doctrines repulsive to the moral sense of a large majority of our community.”

The Convention continued the next day.

They reconvened in Sarah Pugh’s schoolhouse.

And the following year they made a point to hold the convention in Philadelphia again.

They reconvened in Sarah Pugh’s schoolhouse.

And the following year they made a point to hold the convention in Philadelphia again.

The Philadelphia Female AntiSlavery Society was integrated fr. the beginning—Black women like Sarah Mapps Douglass & Margaretta Forten were among its founders.

But no Black woman was invited to join the deliberately co-ed delegation to the World AntiSlavery Convention in London.

But no Black woman was invited to join the deliberately co-ed delegation to the World AntiSlavery Convention in London.

Sarah Pugh was, along with Lucretia Mott & several others.

When they arrived in London the women were feted with teas, but weren’t welcome to be delegates at the convention.

Sarah Pugh wrote the letter of protest. “While as individuals [the women] return thanks for these favors

When they arrived in London the women were feted with teas, but weren’t welcome to be delegates at the convention.

Sarah Pugh wrote the letter of protest. “While as individuals [the women] return thanks for these favors

...as delegates from the bodies appointing them they deeply regret to learn” they will be excluded from acting as “coequals in the advocacy of Universal Liberty.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton wasn’t a delegate, but her husband was. Witnessing the insult to Mott and the other women

Elizabeth Cady Stanton wasn’t a delegate, but her husband was. Witnessing the insult to Mott and the other women

made a lasting impression on Cady Stanton.

Eight years later she and Mott would convene a women’s rights meeting in Seneca Falls, New York.

Sarah Pugh supported the developing women’s rights movement, but devoted herself to ending slavery.

Pugh was a doer, not a strategist.

Eight years later she and Mott would convene a women’s rights meeting in Seneca Falls, New York.

Sarah Pugh supported the developing women’s rights movement, but devoted herself to ending slavery.

Pugh was a doer, not a strategist.

She chaired meetings, gathered signatures, and organized the craft fairs that funded the abolitionist movement for 25 years.

When Pugh first met Frederick Douglass, he was 24 years old.

She met Harriet Jacobs shortly after publication of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

When Pugh first met Frederick Douglass, he was 24 years old.

She met Harriet Jacobs shortly after publication of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

In 1855, Pugh and Lucretia Mott acted as bodyguards for Jane Johnson. They surrounded Johnson as she risked her freedom to appear in court after her sensational escape from her enslaver. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/courageous-tale-jane-johnson-who-risked-her-freedom-testify-those-who-helped-her-escape-180976302/

After the war Pugh embraced women’s suffrage, though the post-War conflict among suffragists pained her.

Privately, she preferred the daring of the National Woman Suffrage Association to the caution of Lucy Stone's American.

Pugh signed the National's 1876 centennial protest.

Privately, she preferred the daring of the National Woman Suffrage Association to the caution of Lucy Stone's American.

Pugh signed the National's 1876 centennial protest.

Pugh doted on Lucretia Mott in the last years of Mott’s life, helping her attend her final women’s rights conference celebrating the 30th anniversary of Seneca Falls.

But Pugh didn’t envy Mott’s husband and many children.

Instead, Pugh created an intentional household of women.

But Pugh didn’t envy Mott’s husband and many children.

Instead, Pugh created an intentional household of women.

She and Sarah Lewis lived together for decades.

From 1856-64, they lived with three other women in “a pleasant home” on Green Street.

The Pennsylvania AntiSlavery Society executive committee met in their parlor.

From 1856-64, they lived with three other women in “a pleasant home” on Green Street.

The Pennsylvania AntiSlavery Society executive committee met in their parlor.

Pugh was particularly close to Abby Kimber, another member of the frustrating 1840 delegation to London. They toured freedmen's schools together after the war.

They are buried in the same plot at Fair Hill Burial Ground.

They are buried in the same plot at Fair Hill Burial Ground.

Sarah Pugh’s diaries were excerpted after her death in an admiring book by her cousins.

Each year on her birthday she would reflect on her faith, her intellectual life, what she had accomplished.

It is a portrait of an unapologetically autonomous life.

/End

Each year on her birthday she would reflect on her faith, her intellectual life, what she had accomplished.

It is a portrait of an unapologetically autonomous life.

/End

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter