The sonnet form remains very much in use and is well esteemed.

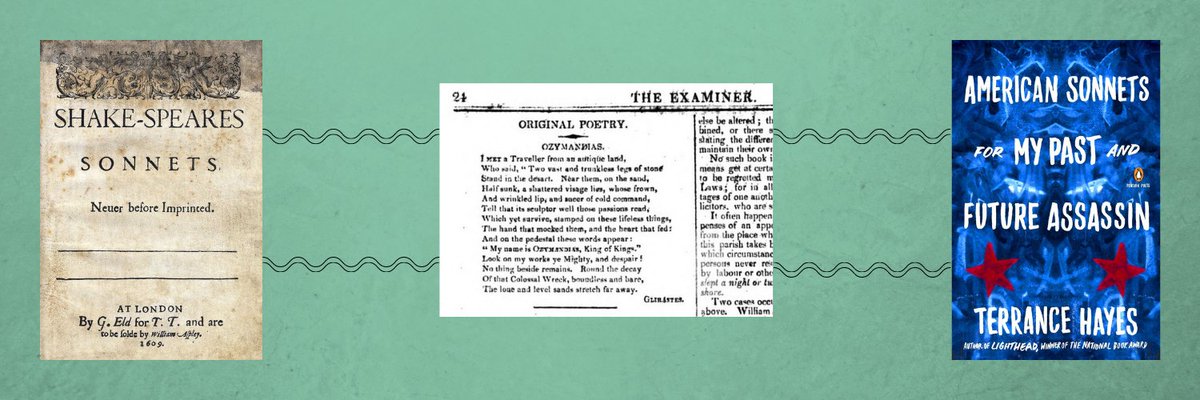

We can look back to Shakespeare's as one of the heights of not just poetry, but English literature overall. "With this key," Wordsworth writes of the sonnet, "Shakespeare unlocked his heart."

We can look back to Shakespeare's as one of the heights of not just poetry, but English literature overall. "With this key," Wordsworth writes of the sonnet, "Shakespeare unlocked his heart."

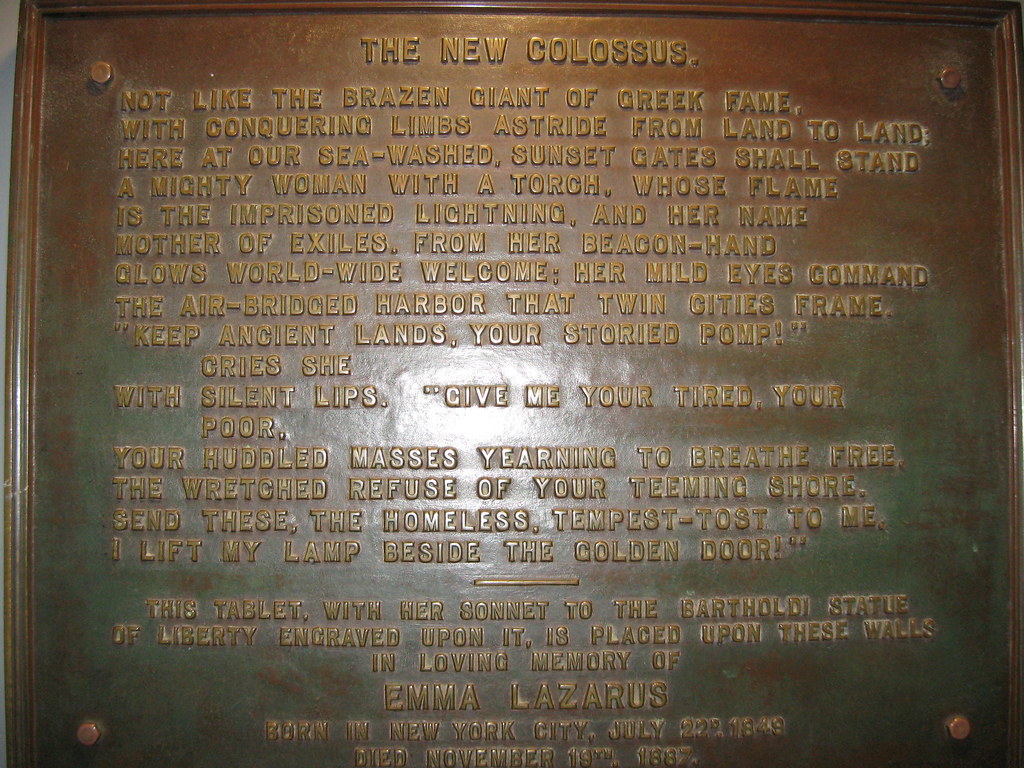

This sonnet, written 1883 and placed inside the Statue of Liberty in 1903, continues to be cited in national debates as though it were a founding document of the country.

(Interestingly, mostly just the part after the volta is quoted. The sonnet structure is somewhat lost.)

(Interestingly, mostly just the part after the volta is quoted. The sonnet structure is somewhat lost.)

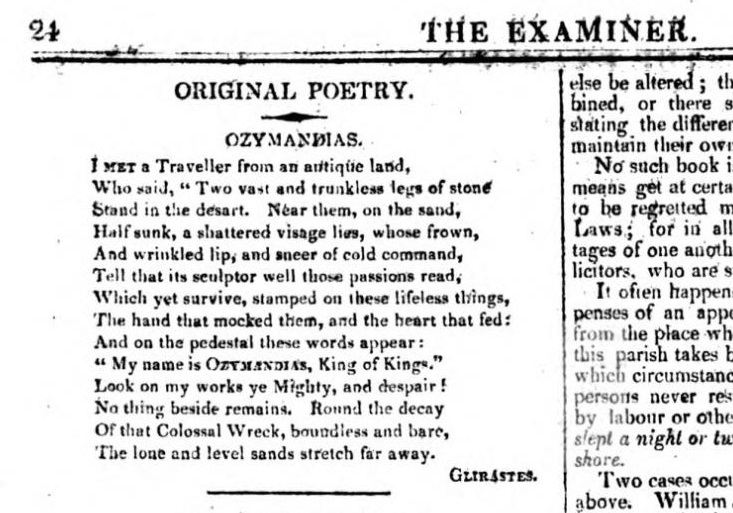

In popular culture, Percy Shelley's depiction of Ozymandias continues to excite the imagination. In particular, the striking impact expressed through the sonnets turn is what is lasting.

That was in 1818.

That was in 1818.

If that was 1818, what could Wordsworth mean in 1826 beginning his own sonnet:

"Scorn not the Sonnet; Critic, you have frowned,

Mindless of its just honours"

In 1803, for instance, sonnets were being critiqued as "stiff difficult trifles." Where does this sense come from?

"Scorn not the Sonnet; Critic, you have frowned,

Mindless of its just honours"

In 1803, for instance, sonnets were being critiqued as "stiff difficult trifles." Where does this sense come from?

The sonnet form had fallen out of popular use, and then revived in the late 18th century.

Prominent was Smith's collection, which also changed the popular content of the form, to "expression of melancholy and sorrowful meditation" (Bishop C. Hunt, Jr.). https://twitter.com/PreCursorPoets/status/1352625818241961987

Prominent was Smith's collection, which also changed the popular content of the form, to "expression of melancholy and sorrowful meditation" (Bishop C. Hunt, Jr.). https://twitter.com/PreCursorPoets/status/1352625818241961987

So you have this history of Shakespeare, Petrarch, Tasso, Camões, Dante, Spenser, Milton, etc., but cast in the light of this current sonnet movement, the sonnet form suddenly seemed much more lowly and trifling to a certain type of critic.

In "Scorn not the Sonnet," Wordsworth praises the "Soul-animating strains" which the form allowed Milton. In "Nuns Fret Not at Their Convent’s Narrow Room," Wordsworth argues that the sonnet form is not "stiff" (per the critic), or a prison, but freeing.

Consider our current perception of sonnets against the 1813 critique as "stiff difficult trifles."

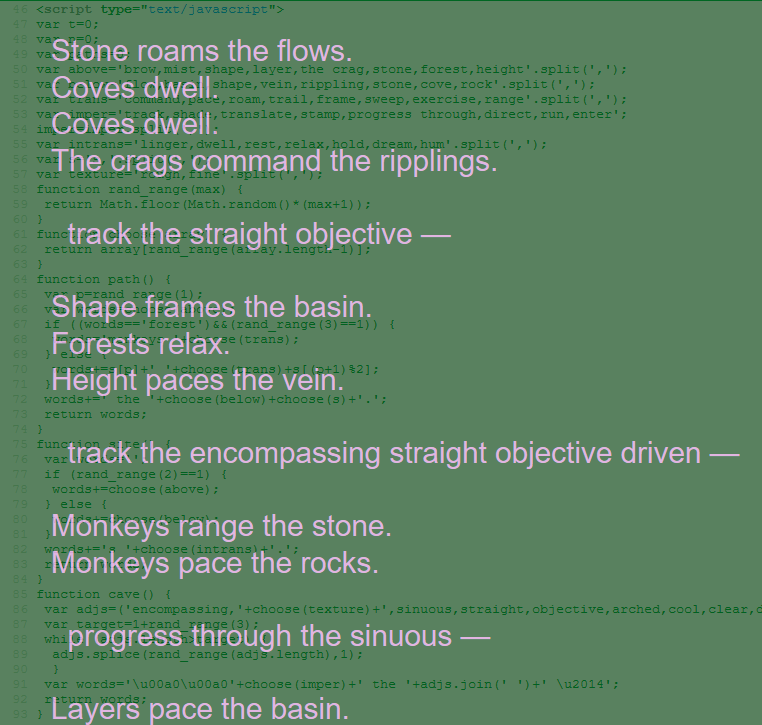

Then consider the stiffness and difficulty of a computational poem, the possible disregard of popular subjects as trifles. In the grand scope of literary history, will this last?

Then consider the stiffness and difficulty of a computational poem, the possible disregard of popular subjects as trifles. In the grand scope of literary history, will this last?

When I polled last month, 80% thought that at least one of the ten most prominent works of poetry from the 2040s would require a computer to read.

So even if you tend not to like current e-poetry, you could learn the fundamentals of the form today. https://twitter.com/PreCursorPoets/status/1343936185626931206

So even if you tend not to like current e-poetry, you could learn the fundamentals of the form today. https://twitter.com/PreCursorPoets/status/1343936185626931206

Or perhaps more enticing, if you look at that history of the sonnet and think digital poetry will inevitably hold a prominent place in the vast poetic tradition, but it does not yet have an "Ozymandias," why wait?

As a reader or a writer, you can learn how that will work today.

As a reader or a writer, you can learn how that will work today.

Far from the only way to learn, but if you can join me on Tuesday, I promise to make the possibilities of this form really come alive and get our imaginations, individual and collective, flowing. https://twitter.com/PreCursorPoets/status/1352416244872437760

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter