Ok, my own answer to @JSEllenberg's question.

Here are some important statements that come up in economics:

"Nice estimators are consistent even in complicated models."

"Nice financial markets are informationally efficient."

1/

Here are some important statements that come up in economics:

"Nice estimators are consistent even in complicated models."

"Nice financial markets are informationally efficient."

1/

"Nice markets have price equilibria."

"Nice games have Nash equilibria."

The way these ideas are taught to Ph.D. economists in any field, even in core courses, involve very explicitly and extensively ideas extending ones in basic analysis.

2/

"Nice games have Nash equilibria."

The way these ideas are taught to Ph.D. economists in any field, even in core courses, involve very explicitly and extensively ideas extending ones in basic analysis.

2/

In particular, those ideas are: convergence (in fairly big spaces), integration and probability/martingales, continuity and fixed points.

Though you could get across aspects of these ideas at a high school level, econ grad school doesn't do them that way.

3/

Though you could get across aspects of these ideas at a high school level, econ grad school doesn't do them that way.

3/

Relatedly, an interesting feature of academic econ is that it seems much more interested in mathematical rigor than, say, physics. So most working economists need not only to understand these ideas but to work, at least a little, with proofs.

4/

4/

While there's no standard math course that perfect practice for the econ kinds of proofs, the one that's the closest is probably basic real analysis, so think of this as the closest-to-relevant training in "proof weight lifting" for what you'll do.

5/

5/

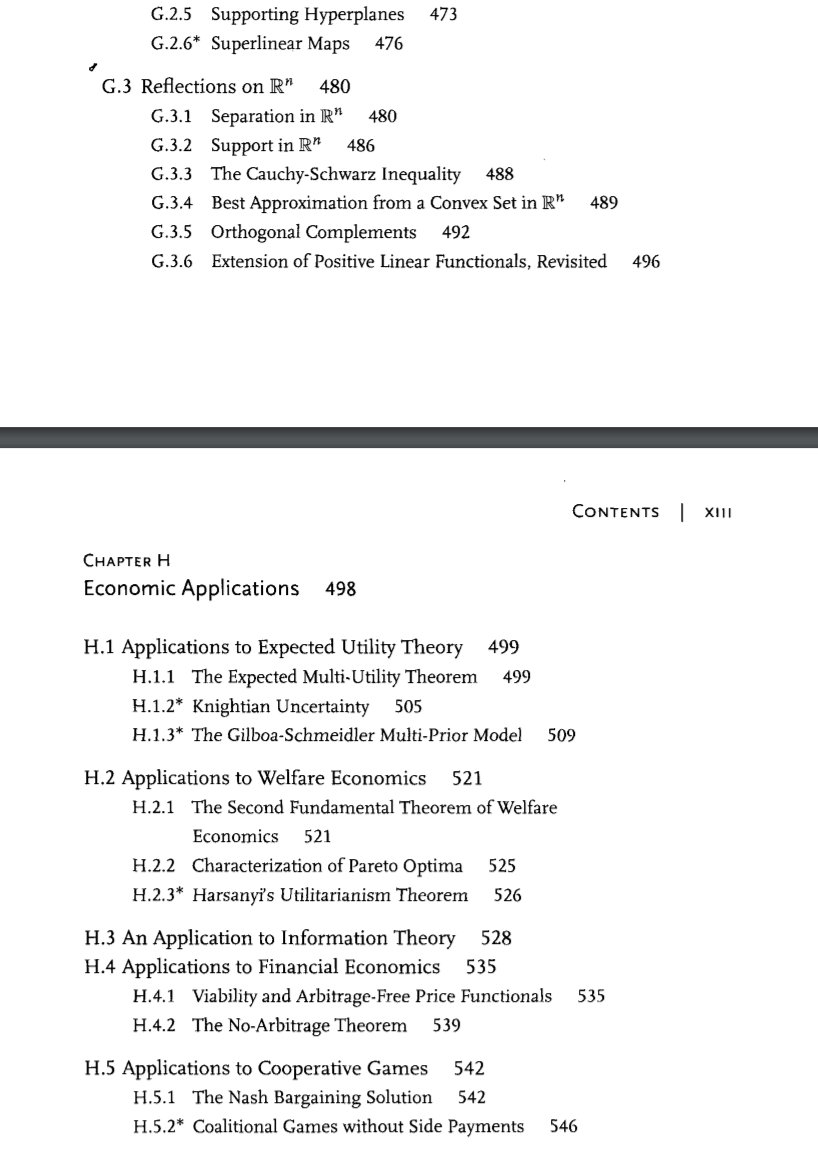

Much more down-to-earth: people interested in social science, finance, etc. who want something to "read along with" a real analysis course might enjoy Efe Ok's book. It develops economic applications right alongside the math.

6/

6/

Despite the fact that basic real analysis can seem a little abstract, the applications in the above screenshot (along with game theory and basic finance theory) might be some of the most direct "practical applications" of real analysis in any field.

7/7

7/7

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter