Why do inequality and deprivation produce high crime and low trust?

Our humble proposition with @danielnettle is out today: http://nature.com/articles/s41598-020-80897-8#code-availability. Here’s a little thread to give a flavour of the theoretical model.

1/

Our humble proposition with @danielnettle is out today: http://nature.com/articles/s41598-020-80897-8#code-availability. Here’s a little thread to give a flavour of the theoretical model.

1/

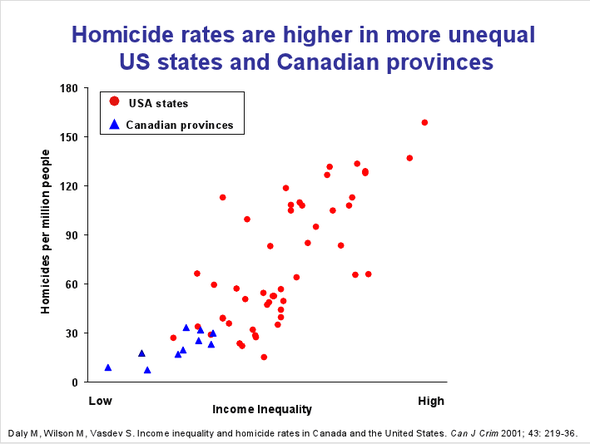

So, countless empirical studies found that unequal and deprived communities are associated with lower trust and higher crime. Such an effect has been found at multiple levels of analysis: countries, provinces, cities, and even neighbourhoods.

2/

2/

Though, there’s no formal model explaining these relations. The evolution of cooperation literature is full of models, but (i) pretends that punishment can stabilise cooperation and (ii) sheds no light on why population-level parameters such as inequalities should matter

3/

3/

Here, we model heterogenous agents in a state-dependent way. Without jargon: our little guys in my laptop differ in their levels of resources, and they decide according to their level. There is no absolute “optimal strategy”, the behaviour is a response to one’s “state”.

4/

4/

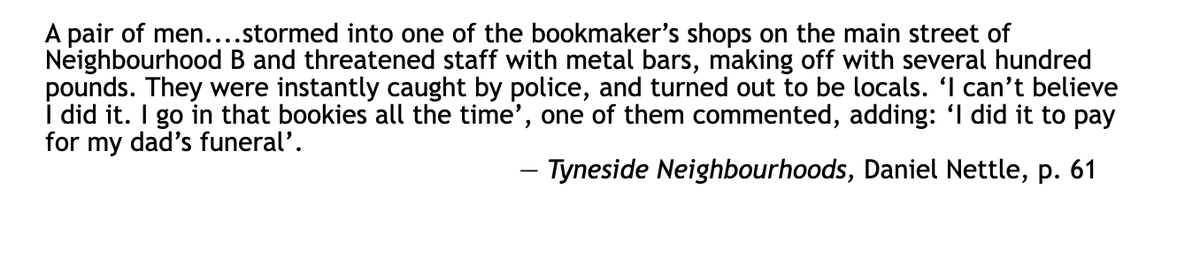

Our intuition is that crime is done in moments of “desperation”. Crime is usually unprofitable as the risks are awful, but can be very rewarding if successful. If you need money right now, (e.g. to pay your rent), stealing it the only way to get a chance to have this money.

5/

5/

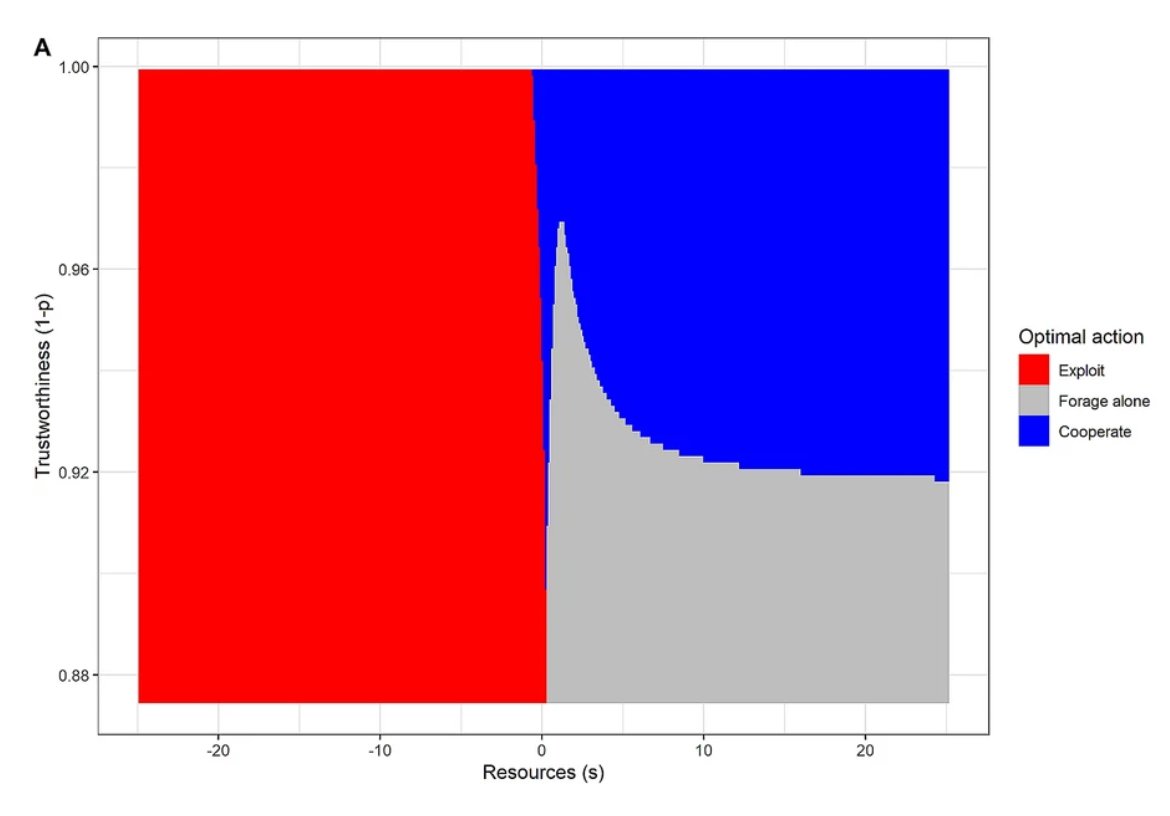

Agents choose between 3 options. They can (i) cooperate, (ii) exploit (on average stupid, sometimes very profitable) or (iii) forage alone (less profitable than cooperation, but safe from exploitation).

6/

6/

Importantly, we also assume that agents are not so much trying to get as many resources as possible, but trying to “stay afloat”, above some “desperation threshold”. The fitness is slashed by some amount for each round spent below the threshold.

7/

7/

This crucial assumption represents the fact that fitness is not a simple linear function of resources. Below some level, fitness is null (it’s starvation). In humans, some needs are deemed “essential”, it is very painful (or socially humiliating) not to meet them.

8/

8/

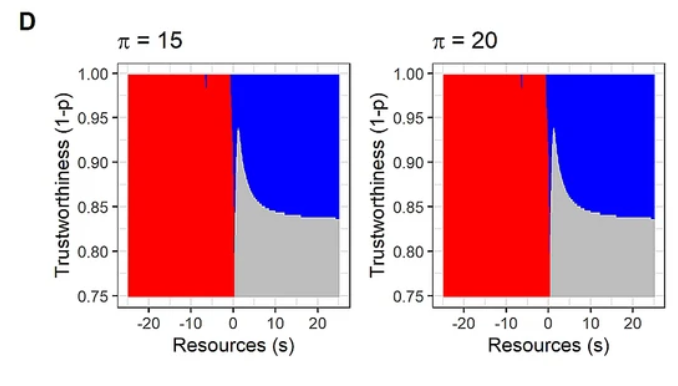

With stochastic dynamic programming, we derived the “optimal policy”, i.e. the best action for each level of resources and of social trust (an estimation of the probability of not being exploited). Below the desperation threshold (0), it is rational to exploit.

9/

9/

The rationale is the following: if you are deprived enough, you need to take a gamble. Though it is on average unprofitable, it gives you the biggest probability to jump back above the threshold.

10/

10/

To catch the intuition, think of football. For goalkeepers, going up and leaving the net empty is usually a very stupid thing to do. But it becomes clever in some circumstances: in the last minutes of the game and when your team is losing.

Reference:

11/

Reference:

11/

Now, let’s look at the population level. If a neighbourhood’s levels of resources are too close to the threshold (deprivation) or too widely spread (inequalities), a significant fraction of people will fall below the threshold. For others, it makes cooperation risky.

12/

12/

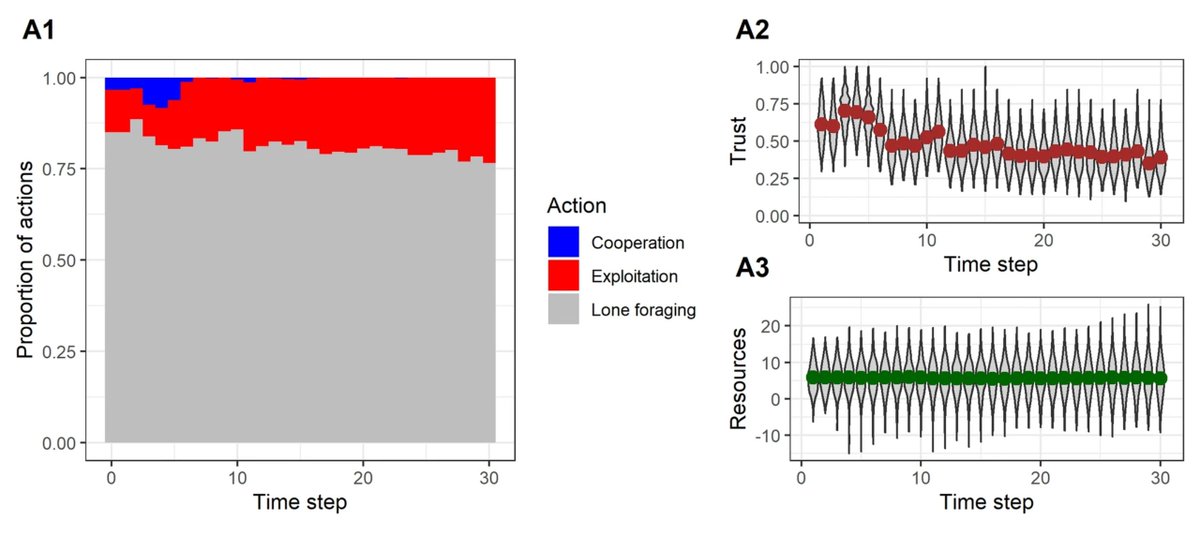

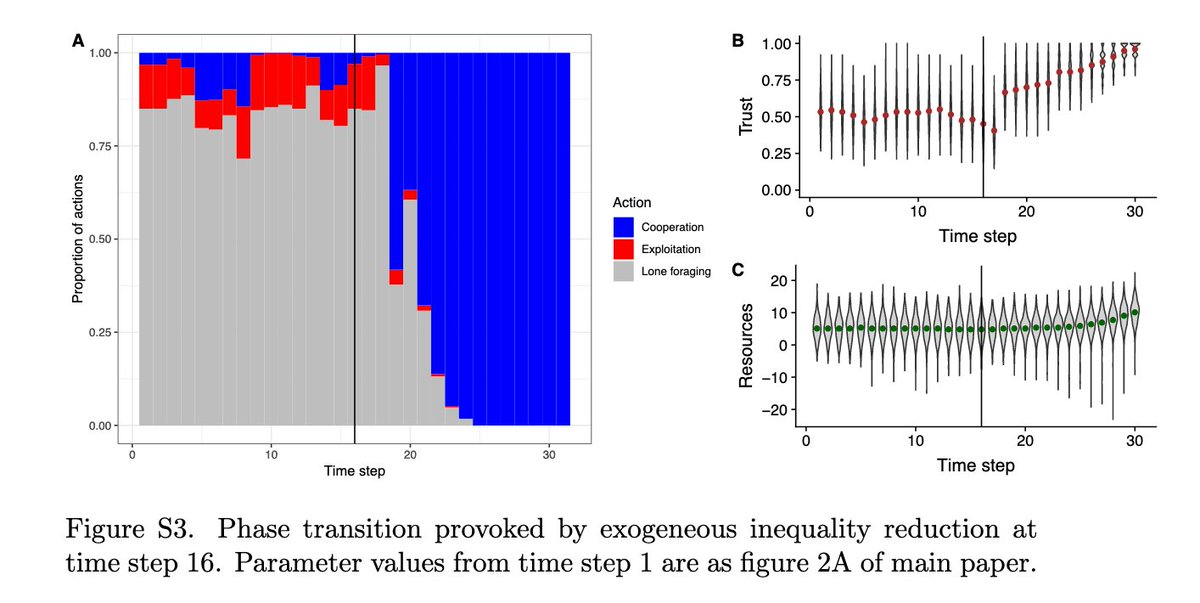

So, an excessively deprived or unequal population will be “trapped” in a low trust and low cooperation equilibrium (left). If you decrease inequalities exogenously (redistribution), cooperation spreads (right).

13/

13/

For nerds, two additional results. First, states also evolve stochastically through a stationary AR(1) process. We called “social mobility” the perturbations' intensity: the bigger they are, the more uncertainty, and the more the social hierarchy is strongly shuffled.

14/

14/

This parameter (r) also impacts cooperation: the more social mobility, the more easily the population will escape the poverty trap equilibrium. For sociologists, this is strikingly reminiscent of Robert K. Merton’s “strain theory”.

15/

15/

On the contrary, the intensity of punishment (imposed on agents who tried to exploit and got caught) has *no* deterring effect. If anything, it makes crime more likely by maintaining agents in desperation. The mad goalkeeper does not care how many goals he might concede.

16/

16/

Interestingly, this is completely at odds with the enormously influential Gary Becker’s “Crime and punishment” model. But it’s what criminologists tend to find empirically. Sorry not sorry, Gary.

17/

17/

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter