2nd of 2 threads on the #digitaltrade provisions in the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement

: This one asks: is the #TCA going to affect AI regulation in the EU?

: This one asks: is the #TCA going to affect AI regulation in the EU?

: This one asks: is the #TCA going to affect AI regulation in the EU?

: This one asks: is the #TCA going to affect AI regulation in the EU?

1st thread on the regulation of data flows and the interim solution for the UK’s adequacy under #TCA (including link to the #TCA and last week's @nyuiilj @megareg_iilj event) here: https://twitter.com/t_streinz/status/1351558893403570184

It’s, of course, impossible to answer the question of how international economic law (in this case: the #TCA) intersects with AI regulation in a Twitter thread (sorry for the clickbait up top!). That’s a whole research agenda.

Later this year @CUP_Law will publish a volume edited by @pengshinyi @chingfulin and myself that lays out some ideas and questions as to what such a research agenda might look like.

One idea is that international economic law regulates trade and investment with regard to the constitutive components of AI: machines/hardware, software/algorithms, and data. If data regulation is also AI regulation, then data regulation in trade agreements is also AI regulation.

In light of the push towards AI regulation that the @EU_Commission announced with last year's white paper on AI https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/white-paper-artificial-intelligence-european-approach-excellence-and-trust_en it is important to consider how existing and new commitments under international economic law might affect this agenda.

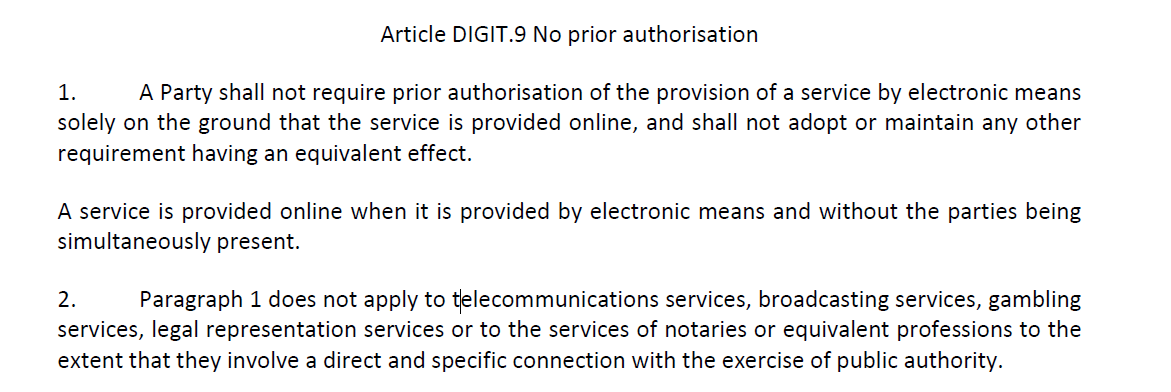

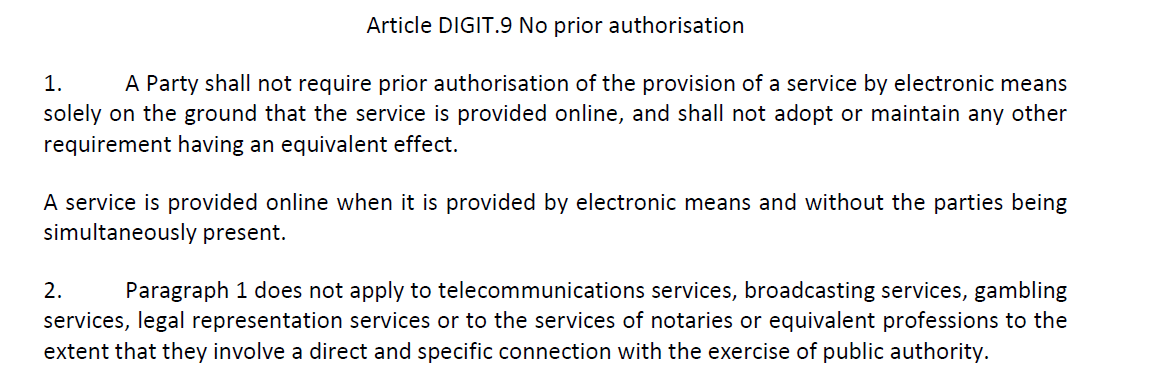

In this Twitter thread let me just hone in on one innocent looking provision in #TCA: Article DIGIT.9 titled "no prior authorisation"

To be clear, this provision is not unique to the

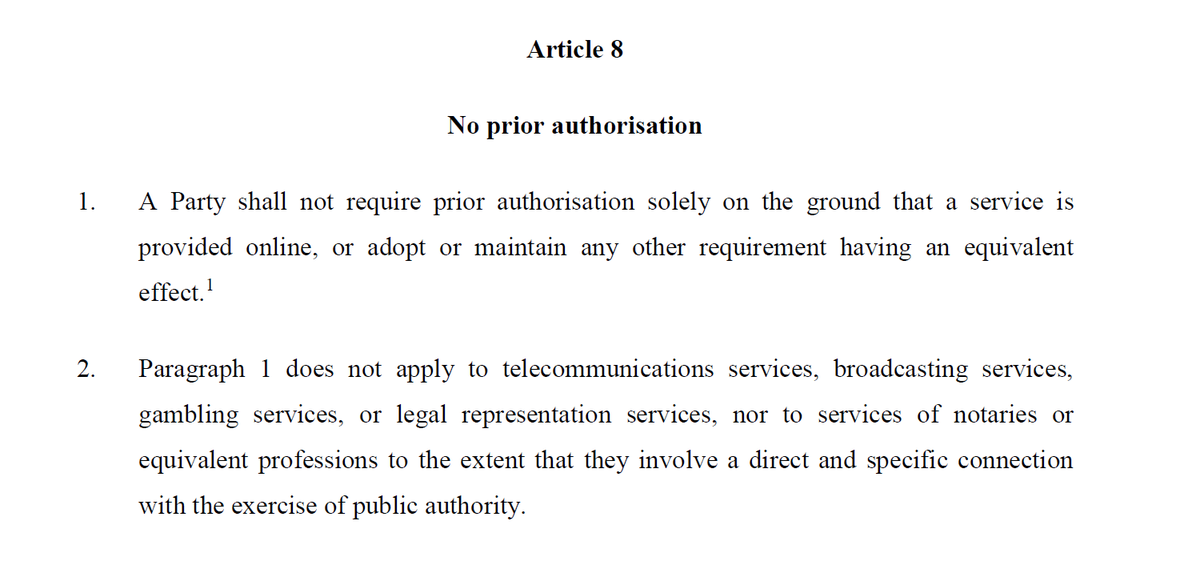

#TCA. An almost identical provision is also included in the EU's proposal for the EU-NZ FTA

#TCA. An almost identical provision is also included in the EU's proposal for the EU-NZ FTA

. It hence seems safe to assume that this was an EU ask, not a concession to the UK.

. It hence seems safe to assume that this was an EU ask, not a concession to the UK.

#TCA. An almost identical provision is also included in the EU's proposal for the EU-NZ FTA

#TCA. An almost identical provision is also included in the EU's proposal for the EU-NZ FTA

. It hence seems safe to assume that this was an EU ask, not a concession to the UK.

. It hence seems safe to assume that this was an EU ask, not a concession to the UK.

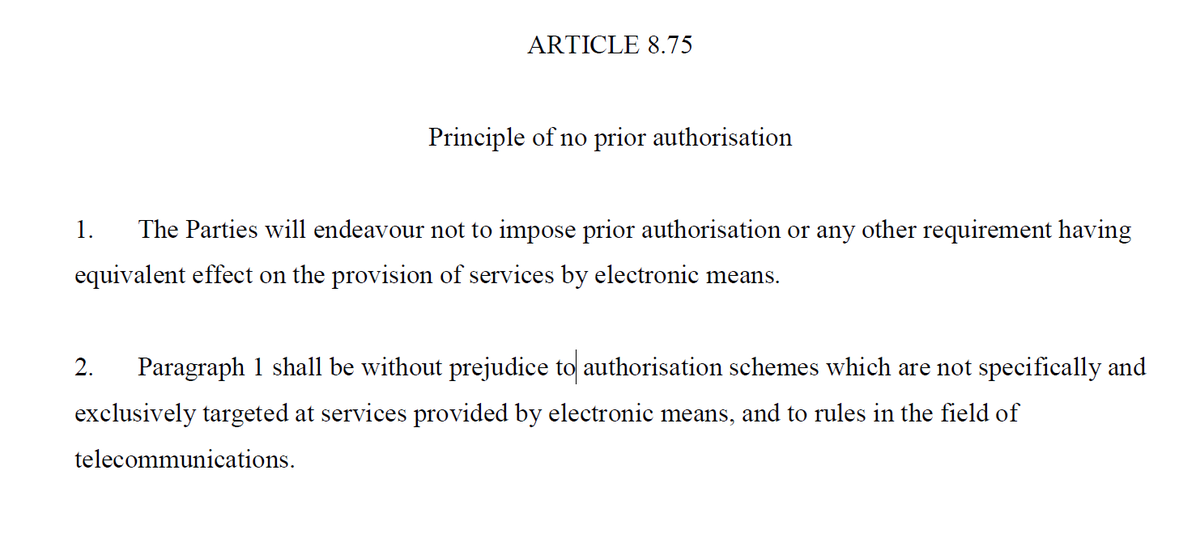

Article DIGIT.9 differs in interesting ways from the analogue provision in

#JEEPA that the UK carried over into

#JEEPA that the UK carried over into

#UKJCEPA

#UKJCEPA

#JEEPA that the UK carried over into

#JEEPA that the UK carried over into

#UKJCEPA

#UKJCEPA

In contrast to #JEEPA, Article DIGIT.9 TCA uses binding language ("shall not") instead of aspirational language ("will endeavour not to"). Moreover, Article DIGIT.9 targets the regulation of services that are provided "online", while #JEEPA speaks of services by electronic means.

What is Article DIGIT.9 TCA trying to achieve? That's the question that the members of the European Parliament should ask themselves and the European Commission as they are evaluating (and voting on) the TCA.

That's the question that the members of the European Parliament should ask themselves and the European Commission as they are evaluating (and voting on) the TCA.

That's the question that the members of the European Parliament should ask themselves and the European Commission as they are evaluating (and voting on) the TCA.

That's the question that the members of the European Parliament should ask themselves and the European Commission as they are evaluating (and voting on) the TCA.

My impression is that this article seeks to outlaw an outdated regulatory paradigm but does so in a way that might affect the emergence of new regulatory approaches in the digital domain, in particular with regard to AI regulation.

Read on its face, Article DIGIT.9 tells regulators not to require prior authorisation *solely* on the ground that services are being provided online.

Through a trade lens, this reads like a non-discrimination provision: online services (which can easily be provided transnationally) ought not to be discriminated against in comparison to non-online services (which are often domestic), by subjecting them to authorisation req.

Note, however, that this article does not require a transnational element at all (which is a frequent feature of "digital megaregulation" https://global.oup.com/academic/product/megaregulation-contested-9780198825296?cc=de&lang=en&). The article also protects *domestic* online services against prior authorisation requirements.

I would be interested to know which concrete regulatory proposals or existing laws (note that DIGIT.9 applies to both!) the treaty drafters had in mind? Which services are subjected to prior authorisation *solely* because they are online?

I am emphasizing *solely* because this word is critical in limiting DIGIT.9's de- or anti-regulatory effects. One *can* read the article very narrowly so that only regulation that's explicitly requiring prior authorisation *solely* because the service is online would be affected.

However, I am concerned that's not how interested parties are going to read this article. International economic law is not only relevant during dispute settlement proceedings. It also shapes the broader regulatory discourse.

The best paper on this phenomenon is by @paulmer and @TimDorlach and published in the Law & Society Review: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/lasr.12495

If lawyers for the global food industry can misinterpret the TBT agreement against food labeling, lawyers for the tech industry can misinterpret #digitaltrade provisions.

On the role of lawyers in coding (digital) capital and in using legal technologies to sustain contemporary informational capitalism let me again recommend (particularly for EU lawyers) the work by @julie17usc @KatharinaPistor and @akapczynski https://twitter.com/t_streinz/status/1348784524784771072

So, to the lawyers out there, ask yourself: how could Article DIGIT.9 TCA be used against AI regulation?

It depends, of course, on what kind of AI regulation a polity pursues. Mere AI ethics won't be an issue (though watch out for a great chapter by @neha_mishra_nm on the interplay between IEL and AI ethics).

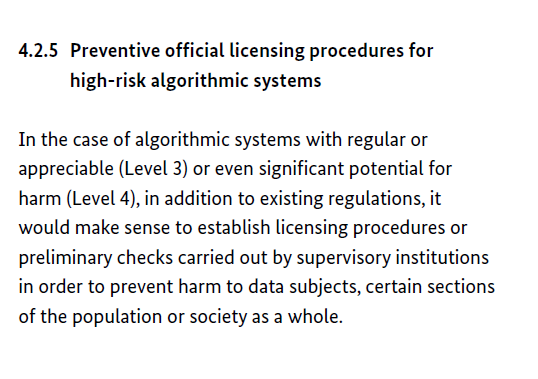

Several expert groups, including the (misleadingly labeled) German Data Ethics commission, have called for licensing requirements, at least for high-risk algorithmic systems https://www.bmjv.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Themen/Fokusthemen/Gutachten_DEK_EN_lang.html;jsessionid=34B2293F696E96B2830C0DCBDEDB7EBC.2_cid289?nn=11678512

So again: if such a regime was adopted, one could of course defend it against Article DIGIT.9 by saying that prior authorisation is required because the algorithmic system is dangerous--not *solely* because it's online.

But interested parties are going to argue the opposite: AI systems are likely going to operate "online" (cloud based) all the time. And that's why they are being singled out for prior authorisation (the argument will go).

That's why it's imperative to rethink our regulatory paradigms as @FrankPasquale has done in his pioneering work on new laws for AI/robotics: https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674975224

The online/offline dichotomy on which Article DIGIT.9 relies is unsustainable. It's almost embarrassing to put this into a treaty in the year 2021 (especially during COVID!). We are constantly connected by electronic means without being (physically) simultaneously present.

That's no new insight at all but it somehow has escaped the drafters of #digitaltrade provisions. I recommend reading @mireillemoret https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/gbp/smart-technologies-and-the-end-s-of-law-9781786430229.html who discusses our life in an "onlife" world.

The "online" terminology is also deployed by @Floridi in his "onlife manifesto": https://www.springer.com/de/book/9783319040929

Internet governance scholar @LauraDeNardis makes a similar point in her book "The Internet in Everything: https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300233070/internet-everything

We are constantly connected. This is not the 1990s anymore, where the fear was that established industries would push anti-Internet regulation (protecting "offline" against "online" services). That's no longer our main concern, is it?

The online/offline distinction needs to be rethought if not retired. And AI lawmakers, particularly in the European Parliament, need to pay attention towards the emerging meta-regulatory framework that the EU and other countries construct in digital economy agreements.

I'm hence directing this thread at leading EU AI experts @NathalieSmuha @PaulNemitz and members of the European Parliament's special committee on AI in a digital age #AIDA: @IoanDragosT @miapetrakumpula @GeoffroyDidier @BirgitSippelMEP @AlexandraGeese @d_boeselager @AndrusAnsip

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter