I’m retweeting this one not because I agree with it, but because I want to emphasize that all of this is so speculative. What does the exclusion of the president’s inability to pardon in cases of impeachment mean? https://twitter.com/steve_vladeck/status/1351511809883193350

Is it only limited when the president is impeached and removed? Clinton’s pardons were allowed to stand, after he was impeached by the House—but the impeachment cause was so trivial—& they were also unrelated to the causes of his impeachment.

I actually think that allowing Clinton to grant pardons after impeachment was a big mistake, one that went against the intention of the Constitution, & one that helped to create the current mess. But that narrow precedent stands. What about the longer history & larger question?

After impeachment, President Johnson gave at least two pardons but they were reversed by President Grant immediately afterwards. How many did he give once impeached? Can other historians pipe in?

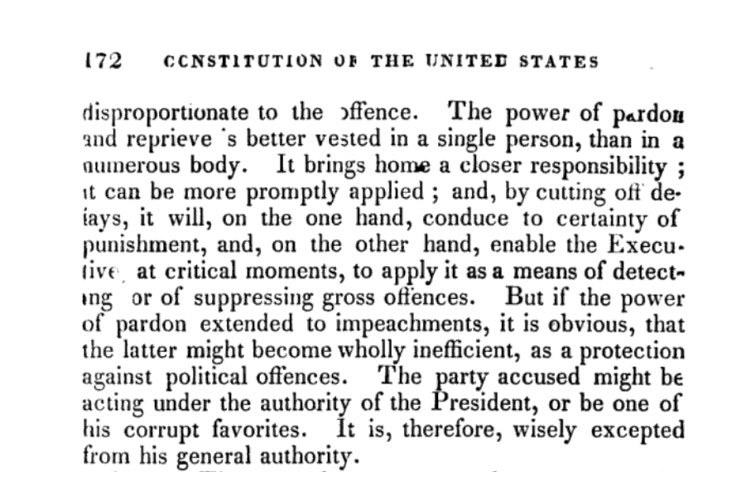

The revised edition of Joseph Story’s textbook of constitutional interpretation, published in 1868, said that presidents cannot pardon after impeachment as such a power “might become ... a protection against political offenses...the party accused might be acting under ...”

We are left with many questions surrounding presidential pardons that have never been litigated in the courts, but that can and in this case should bring us back to a deeper discussion of the debates during the Const. Conv. so we can see what the “except” clause meant.

There are strong grounds for an understanding of the “except in case of impeachment” that is broad—that is meant to thwart the president from pardoning those colluding with him in the effort that led to impeachment . The Constitutional debates show deep awareness of monarchical

Abuses of power. They were aware of and concerned about exactly the predicament that Trump has created. Why? Because this had been a key issue of dispute in English history. And was even part of the Settlement Act of 1701. They were also aware of abuses by their own governors.

At the Constitutional Convention, Edmund Randolph said that even allowing a president to pardon for treason “was too great a trust. The president may himself be guilty. The Traytors may be his own instruments.” While final clause in Const. allowed pardons for treason generally

The debate seems to me — to make clear— that they intended the impeachment exclusion to prevent exactly the scenario that Randolph outlined. As Wilson argued: if the president “be himself a party to the guilt he can be impeached and prosecuted.”

In other words: the impeachment exception was precisely meant to exclude a corrupt president like Trump, who has engaged in treasonous activities, from being able to pardon those who helped him, from pardoning “his own instruments.”

I conclude with a brief comment about the difficulties of determining original intent, and a remark about the imperfections of the founders. While they had many faults, they certainly understood the potential for corruption, including in the person chosen president.

For a marvelous discussion of interpreting intent through the imperfect lens of the surviving notes on the Constitutional Convention, see Mary Sarah Bilder’s _Madison’s Hand_

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter