Preregistration helps to distinguish planned "confirmatory" tests of a priori hypotheses from unplanned "exploratory" tests of post hoc hypotheses. However, some people argue that this distinction doesn't really matter.

Let’s talk about that!

A THREAD…

Let’s talk about that!

A THREAD…

Some people argue that the *type* of hypothesis generation (deductive vs. inductive) is more important than the *timing* of hypothesis generation (a priori vs post hoc; e.g., Worrall, 1985, 2010, 2014).

In particular, we can distinguish between: (a) a deduction from pre-existing theory and evidence (“prediction”) and (b) an induction from the current research results (“accommodation”).

According to this deduction-induction perspective, hypothesis testing is valid as long as hypotheses have been deduced from pre-existing theory and evidence (prediction).

Importantly, as I discuss here, hypothesis testing is valid even if this deduction has occurred in a secretly post hoc manner after the researcher has become aware of their results (i.e., “post hoc prediction”; HARKing; Rubin, 2019). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1bGIUjHSEAoJYJke6RWtBphXJjZLr1UeX/view?usp=sharing

Indeed, in his nuanced discussion of HARKing, Kerr (1998) acknowledges that the independence of theory from current results may be more important than the timing of its generation.

https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0203_4

https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0203_4

From the deductive-inductive perspective, hypothesis testing only becomes potentially problematic when this independence is compromised because information from the current test data is used to induce the test hypothesis (i.e., accommodation).

So, for example, if you induce Hypothesis A solely on the basis on Result A, then you can't use Result A to claim support for Hypothesis A, because you've already used it as the rationale for Hypothesis A (i.e., you can't "double-dip" the hypothesis-chip in the result-sauce).

In summary, according to the deduction-induction perspective, the distinction between a priori and post hoc prediction is irrelevant because, in both cases, the prediction is deduced from pre-existing theory and evidence.

In contrast, the distinction between prediction and accommodation is relevant because prediction is based on deduction from independent theory and evidence, whereas accommodation is based on induction from the current result.

Hence, preregistration is not required to distinguish between a priori and post hoc predictions, because this distinction is irrelevant to hypothesis testing (see also Devezer et al., 2020; Keynes, 1921; Rubin, 2020; Szollosi & Donkin, 2019; Worrall, 2014).

Instead, the important difference is between prediction and accommodation. However, preregistration is not needed to distinguish between these two forms of hypothesis generation because….

…readers can check the rationale for a hypothesis to ascertain whether (a) the current results are required to derive the hypothesis (accommodation) or (b) the hypothesis has been logically deduced from pre-existing theory and evidence (prediction; either a priori or post hoc).

Of course, researchers can deduce a potentially infinite number of predictions from pre-existing theory and evidence, and so post hoc prediction allows them to deduce a prediction that fits their current results.

However, during inference to the best explanation, we should be concerned about (a) the relative quality of the theory and deduction, (b) the diagnosticity of the test for the prediction, and (c) the relative fit between prediction and result.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1bGIUjHSEAoJYJke6RWtBphXJjZLr1UeX/view?usp=sharing

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1bGIUjHSEAoJYJke6RWtBphXJjZLr1UeX/view?usp=sharing

To conclude, I want to share a few select quotes that consider (a) the irrelevance of the distinction between a priori prediction and post hoc prediction and (b) the importance of the distinction between prediction and accommodation.

First up is Brush (2015, p. 78), who contrasts the scientific meaning of the word “prediction” with its lay meaning in order to make way for the concept of post hoc prediction or “prediction of the past.”

https://books.google.com.au/books/about/Making_20th_Century_Science.html?id=6H70BgAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y

https://books.google.com.au/books/about/Making_20th_Century_Science.html?id=6H70BgAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y

Next, Szollosi and Donkin (2019) argue that the distinction between prediction and postdiction (i.e., a priori and post hoc prediction) is “irrelevant” given that both are (deductive) implications from theory.

https://psyarxiv.com/suzej/

https://psyarxiv.com/suzej/

Even staunch preregistration advocate De Groot (1969, p. 90) agrees that the distinction between “prediction” and “postdiction” is not “fundamental.”

https://books.google.com.au/books/about/Methodology.html?id=yMl7zQEACAAJ&redir_esc=y

https://books.google.com.au/books/about/Methodology.html?id=yMl7zQEACAAJ&redir_esc=y

Keynes (1921, p. 350) argues that a priori and post hoc theory is the same if it receives equal support from “general considerations” (background knowledge).

(Note that researcher impartiality can be checked via open research data and materials.)

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/32625

(Note that researcher impartiality can be checked via open research data and materials.)

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/32625

Devezer (2020, p. 18; @zerdeve) argue that valid statistical inferences can be achieved either before or after researchers observe their data and, with proper conditioning, even after they use the data.

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.26.048306v1

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.26.048306v1

Similarly, Oberauer and Lewandowsky (2019; @STWorg) explain that the temporal order of hypotheses and data analyses is “superficial,” and that what really matters is whether the choices of hypotheses and analyses are (theoretically) justified or arbitrary.

https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-019-01645-2

https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-019-01645-2

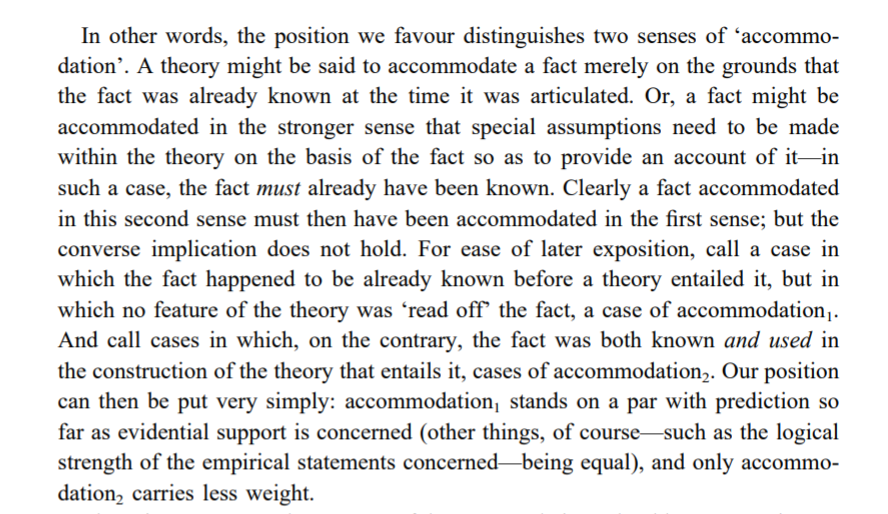

Scerri and Worrall (2001, p. 424) distinguish post hoc prediction (“accommodation 1”) from accommodation (“accommodation 2”) and argue that post hoc prediction has the same value as a priori prediction and greater value than accommodation.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-3681(01)00023-1

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-3681(01)00023-1

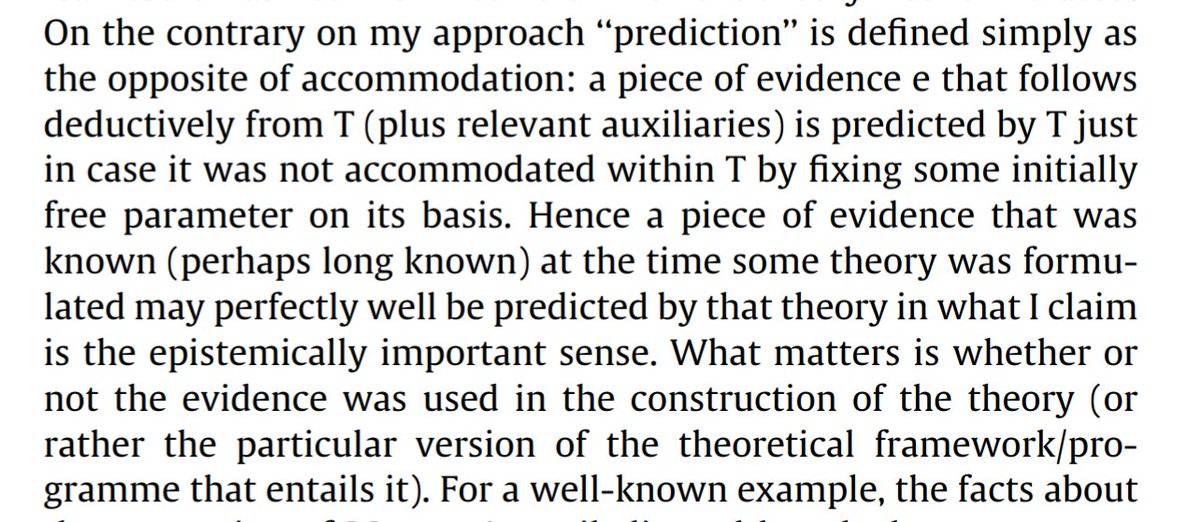

Worrall (2014, p. 55) provides a useful distinction between prediction and accommodation that hinges on whether evidence has been used to fix (specify) an otherwise free parameter in a theory.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2013.10.001

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2013.10.001

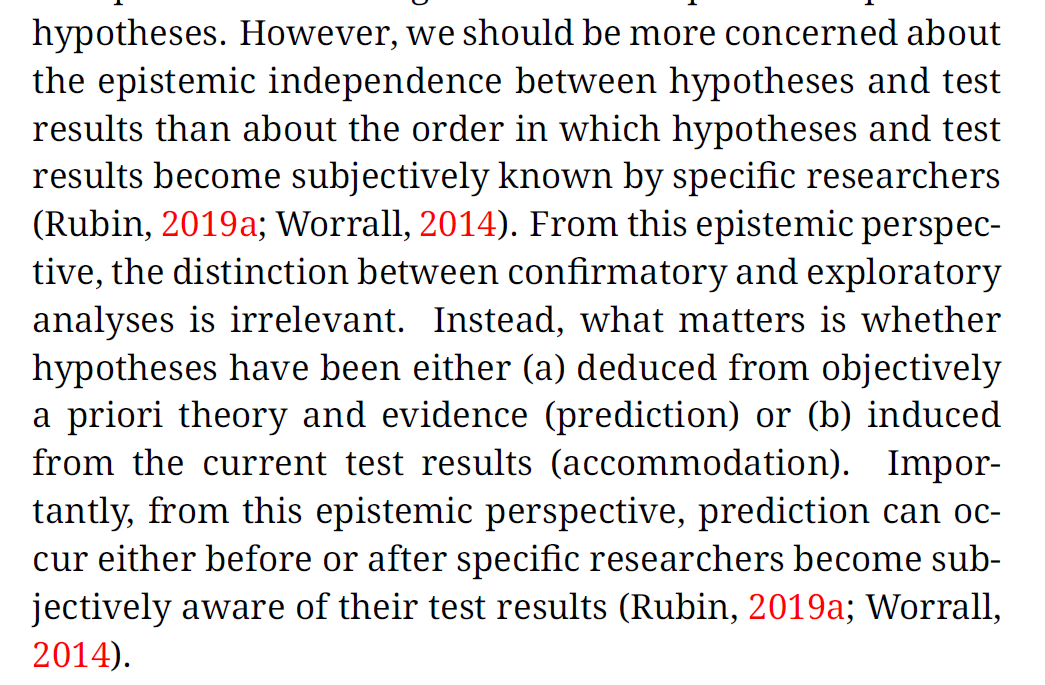

Finally, I argue that the distinction between confirmatory and exploratory analyses is irrelevant, and what really matters is the distinction between deductive prediction and inductive accommodation (Rubin, 2020, p. 379).

https://www.tqmp.org/RegularArticles/vol16-4/p376/p376.pdf

https://www.tqmp.org/RegularArticles/vol16-4/p376/p376.pdf

In summary, several philosophers and scientists think that a priori predictions have the same value as post hoc predictions, and that the distinction between them is “irrelevant" and "superficial."

According to this view, it is not necessary to distinguish a priori and post hoc prediction using preregistration.

Accommodation can have less value than prediction. However, preregistration is not needed to identify this type of hypothesis generation, because it can be readily identified in the rationale for a hypothesis.

I should note that there are plenty of other reasons for preregistration. I undertake a critical review of some of these reasons in my 2020 paper here. I conclude that preregistration is not useful when other forms of transparency are available. https://drive.google.com/file/d/16e4cUDJQ_ZhFxp18OygLyt-uMprbOd4z/view?usp=sharing

OK. That’s it for this mammoth thread! Thanks for listening, and hope you found it interesting!

END

END

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter