#HistoryKeThread: Mutiny Of The Panyako

As #WW1 raged in Europe, the British sought to recruit more Africans into the King’s African Rifles (KAR) . There was need by the British to bolster their troop numbers on the Taveta front, where they faced a large contingent of German troops in German East Africa (Tanganyika).

In Nyanza region, if one was forcefully conscripted, he became the laughing stock of their women. For anyone to be forced to join the KAR, the women believed, he must have been a sissy - a coward of a man.

Let’s pause there for a moment and fast-forward to 1939.

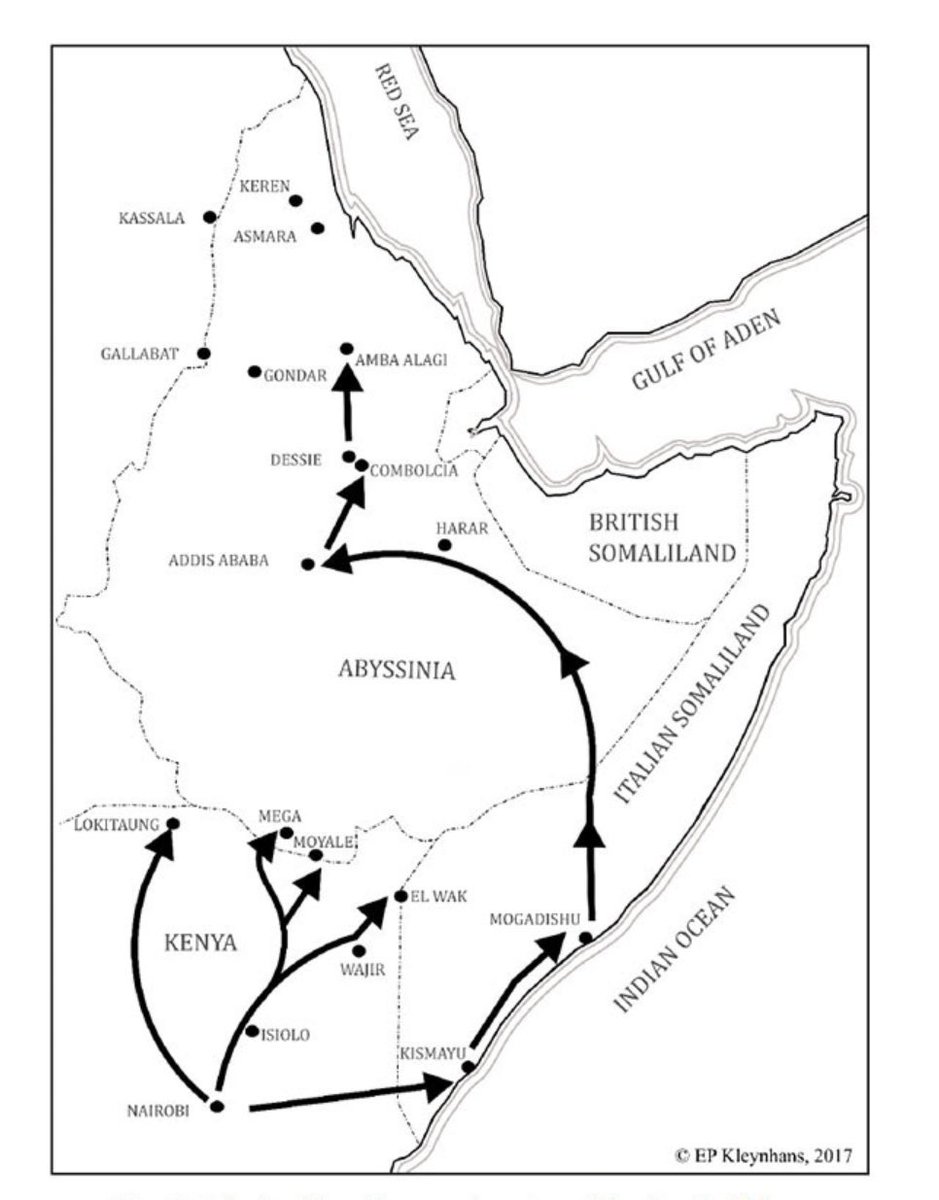

In that year, there were fears that World War 2 would break out. Italy under their fascist leader Mussolini had taken control of Ethiopia, whose leader, Emperor Haile Selassie, was consequently forced into exile in the United Kingdom.

There were at least 100,000 Italian troops in Ethiopia. Back in Rome, Mussolini threatened to invade territories of Africa that were under British control.

This was a nervy prospect for the colonial government in Kenya. The fear was that Kenyan forces would be greatly outnumbered if the Italians decided to roll their war machine across the border into Kenya.

The threat of war also caused consternation among settlers. They were concerned that military officials would take over their african farm labour and channel it into the army.

In actual fact, the colonial government was thinking about the impact of war on farm production. They did not want war to disrupt labour supply in settler farms.

So a plan was hatched to come up with an African “Labour Corps”. This was a force that could be called upon to, among other things, build roads and bridges as well as undertake such other works as would be necessary for the military in case of war.

The government didn’t want to employ a strategy that had proved extremely unpopular among Africans during World War 1, when at public meetings convened under the pretext of government barazas, many Africans were frequently kidnapped and forced to military labour camps.

This time round, government officials believed that if young men started running away from their homes out of fear of forced recruitment, and the military took over control of the remaining African labor, there would be shortage of labour, and conflicts between....

....civilian and military authorities would ensue, putting the interests of the colonial government and the powerful settler class in colonial Kenya into jeopardy, and, overall, undermining the ability of the govemment to mount a formidable defence against an Italian invasion.

So there was need to devise a plan that would endear the proposed Labour Corps to Africans.

In March of 1939, the Chairman of the “Manpower Committee of Kenya” circulated a communique to various heads of Kenya‘s provinces soliciting suggestions on the formation of the Labour Corps.

In those years, the colonial government considered “warlike tribes” to comprise of Maasai, Samburu and Kalenjin. Indeed, many tribesmen from those communities were recruited into the KAR.

On the other hand, “non-warlike tribes” considered for non-combat roles such as supply of manual labour included the “Kavirondo” (Luo), Kamba, Gîkûyû, Meru and communities from the Kenyan coast.

It was eventually proposed that members of the Labour Corps be drawn from communities found in western Kenya and, specifically, from Nyanza Province.

The region, it was argued, had an “inexhaustible reservoir” of labour.

The region, it was argued, had an “inexhaustible reservoir” of labour.

A target of 3,000 men was set and a camp put up at Ahero.

During the ensuing recruitment exercises, however, locals had a problem with the word “Labour Corps”.

During the ensuing recruitment exercises, however, locals had a problem with the word “Labour Corps”.

The name was deemed demeaning. Conscripts wanted people in the village to know that they were brave, and that they had been recruited not to help build roads and dig latrines, but to fight real war.

Conscripts also demanded to be given first priority whenever there were vacancies in the main fighting force - the KAR. To this demand, the military acceded.

To appease the conscripts, the military also decided to do away with “Labour Corps” and rechristen the unit “Pioneer Corps”.

The word “Pioneer” in England has military origins. It is from the French word “pionnier” and referred to “one of an advance company of soldiers,” whose task in western armies was to travel ahead of fighting units to “clear and make roads”.

To the conscripts, the name “Pioneer Corps” sounded macho. They could live with “Panyako”, as they called the unit, obviously a corruption in pronunciation (the word “corps” is pronounced “Koh”, hence “Panyako”. Some people from western Kenya bear the name Panyako to this day).

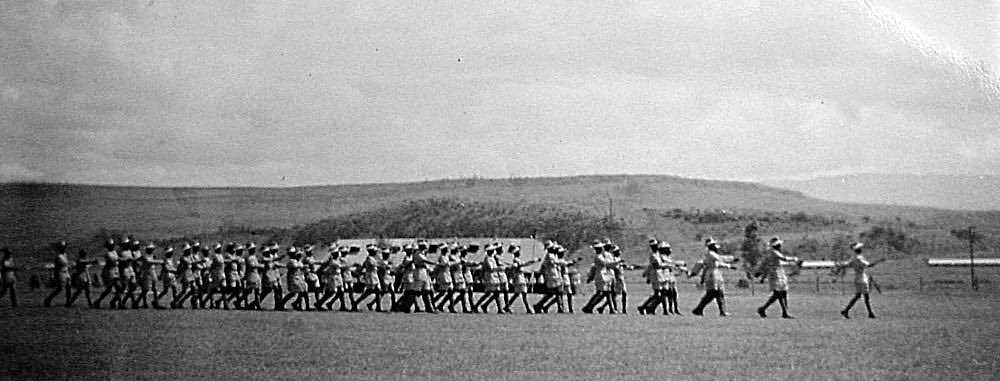

By 3rd July 1939, training was underway at Ahero, where the military managed to recruit 350 men into the Corps.

Then after a few weeks, there was another problem - an unrest, or sort of mutiny - took place.

Then after a few weeks, there was another problem - an unrest, or sort of mutiny - took place.

Pioneers at the Nairobi camp confronted officers and demanded to know why the military had not armed them with rifles as promised during recruitment.

“You told us that we were as much askaris as the KAR because they cannot fight unless they have roads for lorries to take supplies to them”, they told officers.

“Surely, if we are ordered on the frontline without arms, we shall be slaughtered like chicken!”

“Surely, if we are ordered on the frontline without arms, we shall be slaughtered like chicken!”

Additionally, Pioneers felt that their French infantry-like pillbox caps with a back flat they wore gave them an inferior status. They wanted to wear slouch hats similar to those worn by KAR askaris.

Determined to stamp out the unrest, which also spread to Ahero, military administrators led by the commanding officer, Lt. Col. Michael Blundell, assured recruits that the Pioneer Corps would be different from the Labour Corps of previous military expeditions.

Further, Force members would be fast-tracked to KAR, and their general terms of service improved.

When civilians learnt that members of “Panyako” would have better chances of joining KAR, earn better pay, carry rifles and “fight like real men”, the number of recruits increased significantly.

As a result, the Ahero camp was expanded.

As a result, the Ahero camp was expanded.

According to researcher Meshack Owino, who wrote on “The Impact Of Kenya African Soldiers On The Creation and Evolution of The Pioneer Corps During The Second World War”, many African soldiers joined the military for economic reasons, while others joined for prestige reasons.

He cites the example of Okola Omolo, for example. Okola was attracted to the military “because certain retired soldiers in his village owned beautiful things like beds, blankets, and curtains in their homes”.

This kind of lifestyle endeared him to the military.

This kind of lifestyle endeared him to the military.

The author also cited the case of Alex Ochieng Onyango, who joined the military on 8th August 1939 because his father told him that that was what “real men" did.

By October 1939, unrest by dissenting Panyako members had been snuffed out. This happened after the colonial government agreed to a raft of concessions.

For example, on 18th September 1939, the government agreed to issue “a quarter” of the pioneers with arms. The entire Force would however be trained on how to use them.

Moreover, a Gazette Notice designated the Pioneer Corps as an official military unit. Pioneers also received a significant pay increase by the end of 1939.

Although the Italians did not attack Kenya, members of Panyako were deployed in the north of Kenya to carry out various kinds of civil and engineering works for the military.

It is worth noting that Lt. Col. Blundell spoke good Luo, and this fact alone helped a great deal in quelling the mutiny.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter