This comment by an @Amnesty researcher is absolutely unacceptable - claiming Azerbaijan’s actions don’t qualify as “aggression.”

Let me give you a better word then to describe the dehumanization & systematic targeting of a group on the basis of their ethnicity - genocide. https://twitter.com/kozlovsky_en/status/1350759310935142401

Let me give you a better word then to describe the dehumanization & systematic targeting of a group on the basis of their ethnicity - genocide. https://twitter.com/kozlovsky_en/status/1350759310935142401

If you’re wondering what he’s referring to, it’s the law related to the permissibility of starting war - jus ad bellum.

He claims that because this principle only applies to international conflict, it can’t apply to Artsakh because it is legally considered part of Azerbaijan.

He claims that because this principle only applies to international conflict, it can’t apply to Artsakh because it is legally considered part of Azerbaijan.

Therefore, this is considered a “non-international armed conflict.”

Under the framework of territorial integrity, states have the right to do what they want in terms of threats to sovereignty (e.g. secession).

Despite this, int’l law still holds them to certain standards.

Under the framework of territorial integrity, states have the right to do what they want in terms of threats to sovereignty (e.g. secession).

Despite this, int’l law still holds them to certain standards.

That being said, states are still beholden to the principles of ‘jus in bello’ or the laws of war.

It has been established in a number of cases that jus in bello is autonomous of jus ad bellum - meaning even if a war is ‘legitimate’, states cannot violate fundamental rights.

It has been established in a number of cases that jus in bello is autonomous of jus ad bellum - meaning even if a war is ‘legitimate’, states cannot violate fundamental rights.

This is where groups like @Amnesty - and the @ICRC - come in.

Their scope is entirely within the realm of ‘jus in bello’ - that is, they investigate abuses perpetrated in conflicts regardless the ‘status’ of the conflict.

They explicitly do not deal with jus ad bellum.

Their scope is entirely within the realm of ‘jus in bello’ - that is, they investigate abuses perpetrated in conflicts regardless the ‘status’ of the conflict.

They explicitly do not deal with jus ad bellum.

There may be exceptions, where under jus ad bellum the aggressor is clearly defined.

But more often than not, they aren’t. The UN provides very narrow criteria for legitimacy or use of force: self-defense, or when authorized by the UNSC in response to an act of aggression.

But more often than not, they aren’t. The UN provides very narrow criteria for legitimacy or use of force: self-defense, or when authorized by the UNSC in response to an act of aggression.

As you can see, most war does not occur within the confines of either.

As such, most groups focus on abuses perpetrated within the context of conflict.

So an @Amnesty researcher weigh in on whether or not this is “aggression” is inconsistent with the org’s mission.

As such, most groups focus on abuses perpetrated within the context of conflict.

So an @Amnesty researcher weigh in on whether or not this is “aggression” is inconsistent with the org’s mission.

It’s also inappropriate, because we know that war isn’t that black and white.

As a group that seeks to uphold the principles of international law, self-determination should be just as important a concept for @Amnesty to address.

It is, after all, a fundamental human right.

As a group that seeks to uphold the principles of international law, self-determination should be just as important a concept for @Amnesty to address.

It is, after all, a fundamental human right.

The challenge here is that self-determination and territorial integrity are (ostensibly) conflicting concepts.

However, under int’l law self-determination is considered to precede territorial integrity in cases where the state has violated the right of a protected group.

However, under int’l law self-determination is considered to precede territorial integrity in cases where the state has violated the right of a protected group.

The most comprehensive document affirming this is the “Declaration on Principles of Int’l Law concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation among States.”

This explicitly states secessionism as a legitimate expression of self-determination when a state violates group rights.

This explicitly states secessionism as a legitimate expression of self-determination when a state violates group rights.

As such, the question of jus ad bellum or whether or not “aggression” occurred is irrelevant when it is clear Azerbaijan violated the rights of the Armenians of Artsakh, legitimizing their recourse to remedial secession as a means of securing their fundamental human rights.

If @Amnesty were to act consistent with its mission, instead of allowing researchers to make spurious ‘legal’ claims about the legitimacy of war, they’d dedicate resources to examining the right to self-determination & how Azerbaijan’s actions violate that very basic principle.

There are other inconsistencies worth addressing, such as his claims that Azerbaijan attacking “its own citizens” doesn’t amount to aggression.

But the Armenians of Artsakh are not citizens of Azerbaijan. In fact, they may qualify (under international law) as stateless.

But the Armenians of Artsakh are not citizens of Azerbaijan. In fact, they may qualify (under international law) as stateless.

Maintaining a situation of statelessness is a violation of international law, which guarantees a right to nationality.

This is left out of @Amnesty’s assessment because of its narrow scope of assessment and reporting.

This is left out of @Amnesty’s assessment because of its narrow scope of assessment and reporting.

There are dangers to only assessing this situation as one of internal conflict, because while jus in bello protects civilians as it would as if it were any other conflict (as per Geneva Conventions) - it doesn’t consider captured combatants to be POWs.

This is because POW is a designation reserved for int’l conflict.

In internal conflict they’re technically “citizens” (which we’ve established, the Armenians of Artsakh are not) and thus subject to domestic law as it pertains to ‘rebellion’ for example. https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/resources/documents/interview/2012/12-10-niac-non-international-armed-conflict.htm

In internal conflict they’re technically “citizens” (which we’ve established, the Armenians of Artsakh are not) and thus subject to domestic law as it pertains to ‘rebellion’ for example. https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/resources/documents/interview/2012/12-10-niac-non-international-armed-conflict.htm

If you’re interested in the application of jus in bello and jus ad bellum in the case of non-international armed conflict, here is a great resource.

As you’ll see, it’s a lot more complicated than @Amnesty’s researcher would have you believe.

https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/other/jus_ad_bellum,_jus_in_bello_and_non-international_armed_conflictsang.pdf

As you’ll see, it’s a lot more complicated than @Amnesty’s researcher would have you believe.

https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/other/jus_ad_bellum,_jus_in_bello_and_non-international_armed_conflictsang.pdf

One aspect left out is the question of ending internal conflict.

What happens if an internal conflict ends on the terms of the group seeking self-determination - as the first Artsakh war did?

A ceasefire was signed that Azerbaijan agreed to that determined de facto boundaries.

What happens if an internal conflict ends on the terms of the group seeking self-determination - as the first Artsakh war did?

A ceasefire was signed that Azerbaijan agreed to that determined de facto boundaries.

Or the fact that the int’l community has treated the Artsakh conflict as if it were an international armed conflict - the UNSC resolutions against Armenia, and the use of the term ‘occupation’ are examples of such.

It shows how int’l law is manipulated to suit political ends.

It shows how int’l law is manipulated to suit political ends.

Ultimately, the int’l v. non-int’l conflict designations are used to avoid dealing with the issue of self-determination.

In all of this, the fundamental rights of the Armenians of Artsakh are ignored, a betrayal of what int’l human rights law is meant to stand for.

In all of this, the fundamental rights of the Armenians of Artsakh are ignored, a betrayal of what int’l human rights law is meant to stand for.

Do you think the framers of the UN Charter & int’l law wanted legal technicalities to determine whether blatant acts of aggression were actually aggression - on the basis of the status of conflict & its victims?

Absolutely not. So why is an @Amnesty researcher entertaining that?

Absolutely not. So why is an @Amnesty researcher entertaining that?

Also, Amnesty approaches Israel-Palestine through the lens of int’l conflict - but by this researcher’s assessment it should be considered internal conflict as it’s a self-determination movement.

This inconsistency reveals flaws in the method of assessment, as well as int’l law.

This inconsistency reveals flaws in the method of assessment, as well as int’l law.

Despite self-determination being considered a fundamental right, its application has always been inconsistent - despite the consistent reaffirmation of this principle in legal theory and practice as an inalienable human right.

It started with Wilson's Fourteen Points, was codified (and applied) by the League of Nations, was central to the Atlantic Charter vision of post-war (WW2) order, enshrined in the UN Charter's first article, integral to decolonization efforts, reaffirmed by the ICCPR, etc.

When it came to defining sovereignty and statehood, the Montevideo Convention (1933) sets the foundation for statehood - defining the basic conditions of sovereignty, and asserting that statehood is 'declarative' meaning sovereignty is not contingent upon external recognition.

The Montevideo Convetion was applied during the Badinter Commission's decision on the dissolution of Yugoslavia.

The commission also applied the principle of uti possidetis - that territory remains with its possessor at the end of war (or dissolution) unless otherwise specified.

The commission also applied the principle of uti possidetis - that territory remains with its possessor at the end of war (or dissolution) unless otherwise specified.

And as previously mentioned, the preference for self-determination over territorial integrity has been established in the Declaration on Friendly Relations, as well as the 1993 UN World Conference on Human Rights, and then applied in the case of Kosovo.

As a final note, aggression is defined in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court as being the use of armed force against another state OR in a manner inconsistent with the UN Charter - which prohibits the use of unauthorized force except in the case of self-defense.

Azerbaijan's use of force was not authorized, nor was it in self-defense. It also violates the inalienable right to self-determination outlined in the UN Charter.

By the Rome Statute definition, Azerbaijan's actions would qualify as aggression.

By the Rome Statute definition, Azerbaijan's actions would qualify as aggression.

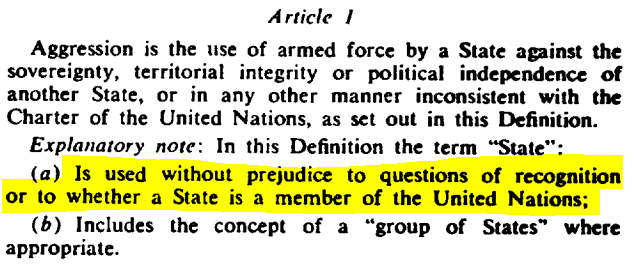

To further clarify, aggression was originally defined by UNGA Res. 3314 and then adopted in the Rome Statute for the purposes of defining the "crime of aggression."

The UN definition, however, has an identical clause re: violations of the UN Charter.

https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/3314(XXIX)

The UN definition, however, has an identical clause re: violations of the UN Charter.

https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/3314(XXIX)

The UN definition of aggression also helpfully clarifies that its definition of a 'state' is not conditional on recognition, or its membership to the UN. This is clearly to take into account aggression directed against non-state actors such as self-determination movements.

This can (and should) be interpreted as a reaffirmation of the Montevideo Convention's definition of declarative statehood (as outlined above, and confirmed through legal precedent) which determines that statehood is not contingent upon recognition.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter