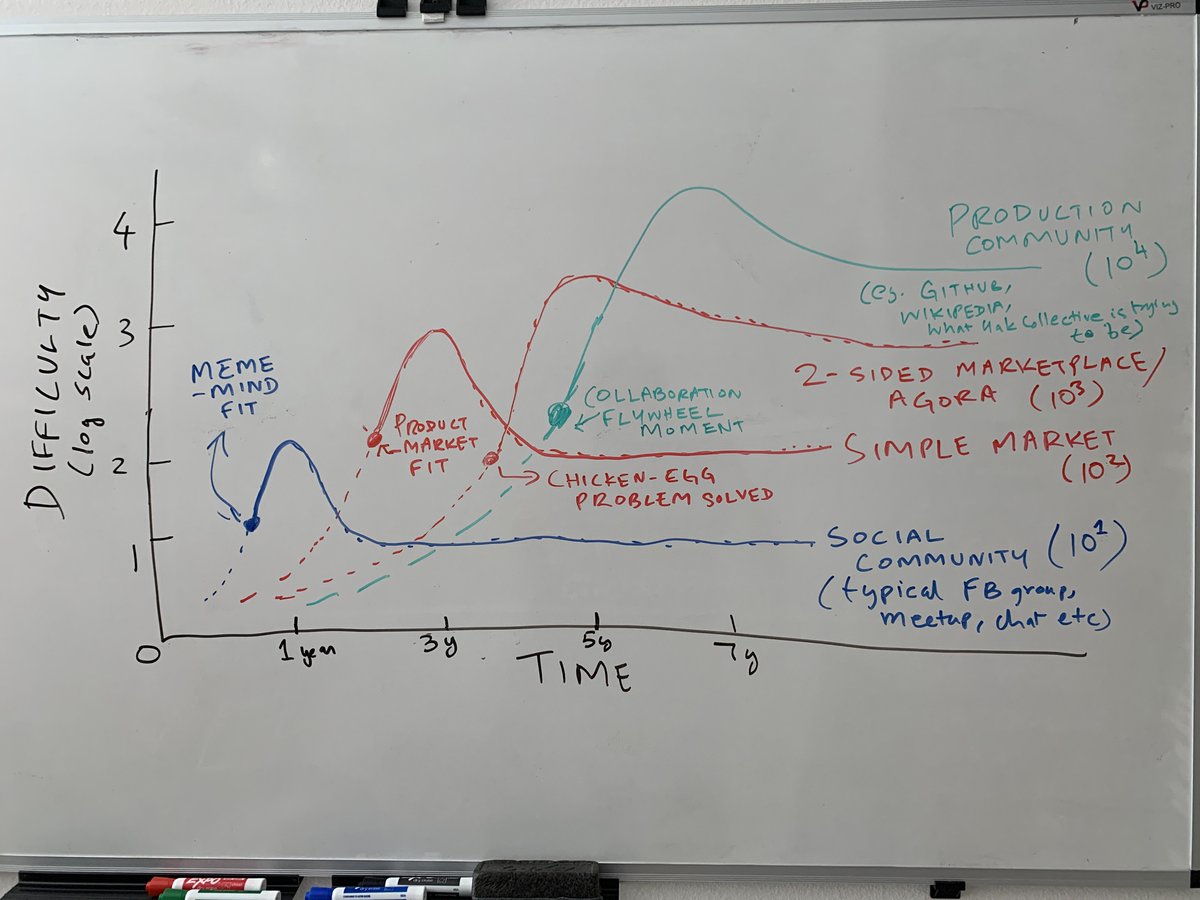

following a discussion at @yak_collective this morning, I came up with this chart to capture a hypothesis I have that the difficulty of creating communities scales exponentially with the the "depth" of what you're trying to do

thanks @grigorimilov for leading the discussion that sparked this.

The way to read the graph is: each line is a time history of difficulty. It starts dotted, goes through a criticality inflection point, and then crests in difficulty before coming down to a stable plateau.

The way to read the graph is: each line is a time history of difficulty. It starts dotted, goes through a criticality inflection point, and then crests in difficulty before coming down to a stable plateau.

The inflection points have different names depending on context, but are all topologically similar. They are the make or break moment when a network-effect either kicks in, or fails to. "Product-market fit" in the case of market is the best known such point.

Level 1 is a basic social community, such as a FB group, meetup etc. There are millions of successful ones, and 100s of millions of failures. The "fit point" is what I call a meme-mind fit, when some social object catalyzes a sustainable long-term conversation of growing richness

Almost everything I've helped instigate is Level 1. My contributions to the social-object soup have been things like the vocabulary around sociopaths/clueless/losers, legibility, 2x2s etc.

Level 2 is 10x harder, and takes 3x as long to get to its fit point typically (3y instead of 1). This is simply creating a customer/simple market for a single product. The product-market fit moment is usually (but not always) a word-of-mouth network effect moment.

This is when you don't just "create a customer" in the Drucker sense, but the customers form a special type of deep community -- a market -- that is an order of magnitude deeper than a merely social one. When you buy together, and create a community of consumption.

Communitarians tend to look down on markets as "impoverished" communities. They are wrong. Shopping and consumption are age-old activities, and a community that has that behavior around a successful product or service (think farmer's market, barber shop) is a richer thing.

I've successfully sold things and made decent money at a personal scale, and I've been a ringside spectator to true PMF moments. Something magical happens when the cash register starts to ring faster and faster like a geiger counter. Something much richer than mere talk.

Level 3 is yet another order of magnitude harder, and takes like 5y to get to its fit moment. In tech, this is often called the "2-sided marketplace" problem, but I think of it as creating a full-blown agora, connecting buyers and sellers of *many* products.

The fit point is when the "chicken-egg problem" is solved: buyers won't show until there are sellers with PMF, and sellers won't show up until there are serious buyers. The "fit" moment is one that looks like a PMF but actually makes the whole market, not just its own market.

Books for Amazon, apocryphally pez dispensers for eBay. These are incredibly rare moments, and there's perhaps only a few dozen in each geography/culture. I've been witness to many failed attempts close up, but never been ringside for a successful one.

But even from a distance, from the cheap seats, the birth of an agora is an impressive site, like a supernova triggering. Suddenly, an entire social space transforms into a buzzing beehive of activity of all sorts. Again, this isn't an impoverished form of a community, but richer

And finally, Level 4, which I'd say is 10^3 harder than a basic community, is a *production* community. They are incredibly rare. The only 2 I can think of online are Wikipedia and Github. Getting a big group of people not just *transacting* things, but *making* new things

The "fit" moment is what I've labeled a "collaboration flywheel" moment, where a robustly generalizable mechanism kicks in and starts catalyzing all sorts of collective creative effort, not just isolated things. There is often a discovery of a key mechanism underlying the moment.

I think for GitHub it was the invention of the pull request. For Wikipedia, it was... I guess the basic wiki mechanism of editing being as low-friction as reading.

tbf, when I was involved in casually instigating the yak collective last year, I hadn't thought this through. I had the initiative miscalibrated as about as difficult as getting a decent Facebook group or meetup going. ie I underestimated the challenge by a factor of 10^3

Building communities that *produce* is 10x harder than building communities that *trade*, which in turn is 10x harder than building communities that *buy*, which is 10x harder than communities that talk.

And even *talk* communities ain't easy. Failure rate is like 95%.

And even *talk* communities ain't easy. Failure rate is like 95%.

In hindsight, it was dumb to not realize from the get-go how hard production community building is. It's not like building a startup, but like growing an ecosystem, like Silicon Valley. Yep... getting something like Wikipedia or GitHub off the ground = building Silicon Valley.

Level 4 is the level at which the adage "Rome wasn't built in a day" applies. In my graph, I've estimated the "collaboration flywheel moment" at the 5y mark, which seems about right. Effort peaks around the 7y mark, and you don't hit the sustainable plateau till like year 10.

The individual effort-rate is actually the same across all levels. Everybody still has only ~16 waking hours in a day, and whether you are building cathedrals or just doing laundry, humans still average only about 100-150 watts of power output. So where does the difference lie?

The difference lies in accepting horizons of commitment. To build a production community, you have to say to yourself something like "so long as this is alive, I'm going to stay involved in it, for at least 10 years."

One of the projects I'm helping kick off at the @yak_collective is literally a 10-year project: the yak rover, with a goal of getting a rover to mars. And yeah, at this stage it is a borderline a joke, but there's a few of us actually getting started...

I have no idea how far we'll get. Certainly if we actually make it to Mars, far more talented people than me will have to get involved. I'm pretty much just futzing around with 3d printing toys and learning to control motors with arduinos. Hardly a space program.

But at whatever level of ability I can bring to the party, I've sort of decided I'm willing to keep tinkering and muddling through on this project for 10 years, while I have some good company. It's like deciding to write a difficult book as opposed to a quick-turn fad book.

I'm not very ambitious, and am pretty lazy and mediocre as far as average effort rate goes. But I do tend to stick with things for really long. Most of my current projects are years old. Some are over a decade old. So I'm optimistic :D

ie, it's not a sprint, it's not a marathon, it's not a "heavy lift" single herculean effort. It's simply the willingness to keep generally heading in a particular direction, at whatever pace/duty cycle (on-off pattern) you can manage, *for a really long time.*

Funny how sheer quantities of lightly committed "involvement time" can be a substitute for a LOT of rarer, more impressive traits like intelligence, peak effort, knowledge, insightfulness etc. More time substitutes dumb trial and error for basically everything.

As the saying goes, 80% of life is just showing up. And if you decide you're just going to show up in a certain activity for long enough, many interesting things can happen that you would have NO talent for under shorter time horizons.

Can't recall where I saw this, but aptitude can be defined as the time it takes you to learn something. It's not that a genius can learn things you can't. Most of the time, it just means it will take you 10-100x longer to get there.

Tortoise-hare something something. If you're not a genius, just check out how long it takes your friendly neighborhood genius to do something and simply commit to doing it too, over 10x time.

The thing that accomplishes that being a genius doesn't is open up potential for collaboration, since there's a lot more people with ordinary levels of aptitude than geniuses. You can collaborate with everybody else who is at your level. You can do overall bigger things.

This sounds like yet another sermon about long-term thinking, but it isn't. It's a sermon about long-term *commitment.* It doesn't take much upfront thinking. I mean, fairly dim people seem to get married at 22 without much thought and make a successful 30-40 marriage out of it.

It sounds extreme, but it actually isn't. The world is full of patterns of almost casual long-term commitments: marriages, 30-year mortgages, having kids, picking a major in college...

We tend to be afraid of long-term involvement commitments because we tend to think they need to be heavily overspecified up front. But a 10 year involvement commitment does not involve a 10 year *plan.* All it implies is picking a direction you'll be muddling-through towards.

The "plan" for a good marriage is basically "stay involved." The plan for being a successful parent is "stay an involved parent for 18 years." There are no milestones and detailed gantt charts.

In fact, the main thing to commit to is a negative, to NOT steer. Because once you develop momentum staying directionally stable is not about doing stuff. Throwing away the steering wheel. I wrote a narrow version of this argument in blog post https://www.ribbonfarm.com/2017/11/09/ceos-dont-steer/

It's a milder version of "burning bridges." Once you decide you're going to "stay involved" in something, there's a certain stability of mutual expectations for everyone who makes that decision. You start thinking in indefinitely iterated prisoner's dilemma mode.

Throwing away the steering wheel, setting long-range involvement horizons... it doesn't guarantee that n an ESS (evolutionarily stable strategy) like tit-for-tat will emerge, but it opens up the possibility that one will https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evolutionarily_stable_strategy

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter