CALLING ALL SCIENTISTS, EDUCATORS, and anyone who's been thinking about the Covid pandemic and the concurrent ***misinformation pandemic*** destroying our country: what are your ideas for how we can keep future generations from suffering the way we are now?

1/

1/

I can't stop thinking about education, particularly science education. Instead of learning the phases of mitosis 10x throughout elementary school to high school, maybe we should focus on critical thinking. Regardless, this would be a great place to start for the youngest kids.

2/

2/

Here are just some of my ideas but I'm sure there are more people with better ones (hence the crowdsourcing). The first thing I'm thinking about is how we teach young kids about "fact vs. opinion." If you Google this, you'll find countless worksheets like this one:

3/

3/

There are so many issues with this worksheet. The first, biggest thing across ALL worksheets I found online is that NONE of these have a third option. The third option should be "False statement." The reason is that people of all ages currently encounter false statements

4/

4/

everywhere they look, and they are misidentifying them as "facts" or "opinions." I think teaching kids that this third option exists could help with several things. 1. Protection from gaslighting. There are *MILLIONS* of people who have been told constantly for months that

5/

5/

"Masks don't work" and "The election was stolen through voter fraud," and they can't fathom that those could be lies ("false statements"). I see adults posting on Facebook, "The election was stolen and that's my opinion, so I'm entitled to it." BUT 1. That's not an opinion and

6/

6/

2. They're not "entitled" to just say anything. These statements can both be evaluated objectively using evidence. Our existing evidence overwhelmingly indicates that these statements are not true. Thus, they are false statements. The second reason why we should teach kids

7/

7/

this third option is that it leads to a discussion of how we know a fact is a fact. There are some things that we can observe firsthand. For instance, I can tell my friend, "The sky is blue right now" and she can look outside and observe it and recognize that it's a fact.

8/

8/

If I say, "The sky's pretty," that's an opinion bc it's subjective and my friend can look at the sky and see if she agrees or disagrees. If I say, "The sky is orange," she can look outside and evaluate the statement and realize that it's blue, and I'm making a false statement.

9/

9/

[Ofc this has nuances, including that it relies on my friend not being in a different time zone where the sky is a different color. And there are people who are vision impaired and people with rare types of colorblindness. Maybe you guys can come up with an airtight example.]

10/

10/

How do we evaluate, though, statements for which we can't observe the evidence firsthand? i.e. when do we trust scientists' evaluation of evidence?

I remember learning the steps of the scientific method, what a scientific theory is (and, broadly, how they're based on

11/

I remember learning the steps of the scientific method, what a scientific theory is (and, broadly, how they're based on

11/

evidence) when we learned about evolution in middle school, and defining primary/secondary/tertiary sources in social studies (i.e. "Anne Frank's diary = primary source, textbook = tertiary source"), but I think we should have a whole, cohesive unit on levels of scientific

12/

12/

evidence and how that evidence is generated. Ideas:

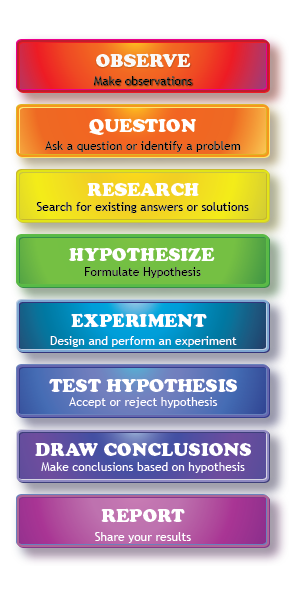

1. (Also brought up by my HS chem teacher when I posted about this on Facebook) The "scientific method" should be taught with more context and concrete examples from the real world. This is a commonly used graphic:

13/

1. (Also brought up by my HS chem teacher when I posted about this on Facebook) The "scientific method" should be taught with more context and concrete examples from the real world. This is a commonly used graphic:

13/

The sci method is represented as linear. It makes kids picture one scientist in one lab starting with one hypothesis, doing one experiment, and making overarching conclusions from that one experiment. There needs to be concurrent discussion about

14/

14/

how multiple experiments are needed to test a hypothesis and how you might be able to draw a conclusion from an experiment, but you'll have to keep testing that conclusion as basically the new hypothesis for your next set of experiments. You also have to think about all the

15/

15/

alternate explanations for your hypothesis, and whether you tested those. You also don't just communicate your science and then it's over. You get input from other scientists in your field on how rigorous your experiments were. Other scientists do the same experiment and

16/

16/

other related experiments in their own labs to generate more evidence for or against your hypotheses and conclusions. I could go on and on about this, but there are so many examples in current events that we could use to explain this to kids. I think the idea of scientists

17/

17/

doing a bunch of iterations of the scientific method and arriving at consensuses is touched on. I think I learned about the cell theory in middle school biology and the different scientists who contributed with their observations and competing theories (van Leeuwenhoek, etc.)

18/

18/

Same with evolution, when we learned about Malthus, Lamark, Darwin. Finally, HS AP Bio touched on the experiments that led to the consensus that nucleic acids carry genetic information, not amino acids. But I'm worried this isn't started at a young enough age and that kids

19/

19/

think this is something that happened in olden times and doesn't still happen all the time. Current examples could help, like discussing why the scientific consensus changed between March and May about whether non-N95 masks are worth wearing to stop the spread of Covid.

20/

20/

I've also been thinking about how maybe when kids learn about Galileo and how he was ostracized and imprisoned for his heliocentric theory, they get the idea that the one person who everyone says is crazy turns out to be right. Maybe this is why adults now watch "Plandemic"

21/

21/

and think the one discredited virologist in that video is probably the one person trying to tell the truth, and everyone else is just trying to hide the truth. Scientific consensuses are reached because lots of people with the right training and expertise reached the same

22/

22/

overarching conclusion by evaluating many different pieces of evidence. As new evidence is discovered, scientific consensus may change (which is my second problem with that "Fact vs. Opinion" worksheet - it says that facts can't be changed)! However, it takes many pieces of

23/

23/

evidence, not just one rando, to change scientific consensus.

This thread is getting way too long so I will write about more ideas later!

24/

This thread is getting way too long so I will write about more ideas later!

24/

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter