What are the key persuasive strategies used by populist nationalists?

A mix of advocative (we the people) & conflictive (discredit & blame elites & 'dangerous others' such as the Left, Muslims & migrants).

Successfully deployed by Nazis, politicians, shock-jocks & the press.

A mix of advocative (we the people) & conflictive (discredit & blame elites & 'dangerous others' such as the Left, Muslims & migrants).

Successfully deployed by Nazis, politicians, shock-jocks & the press.

'Populism’ has become synonymous with the radical right, & as such, discourses filled with hate, anger, fear & nostalgia for a glorious past. Populist voters are demonized & accused of acting out of rage, or voting based on gut-feelings rather than reasoning & deliberation.

Often they are dismissed as bigots or a “basket of deplorables”. Mainstream parties across Europe denounce populist parties as irresponsible actors for fuelling emotions, rather than fostering a rational debate, and thus causing political & civic turmoil.

This is antagonistic.

This is antagonistic.

And such an approach is problematic in that it dismisses populism as 'irrationality en masse', downplaying the often legitimate grievances & concerns of populist voters (eg secure jobs & housing) as irrelevant or wrongly placed.

Populists are stereotyped as irrational & emotionally driven, but in decision-making, there is a conjunction between emotions & cognition, which work together in guiding our understanding: ‘thoughtful & deliberate’ decisions involve processes that are prominently affective.

Conservative thinking can be a response to a need to reduce fear & uncertainty, with experimental evidence that priming mortality threats (via terrorism) results in post-manipulation conservative identification.

Liberals are less concerned with fear & characterised by a higher propensity for empathy. This emotion emerges as a distinctive trait of liberal ideology in a number of studies, highlighting its centrality in underpinning attitudes toward social spending and the welfare state.

The relevance of emotions in politics can be seen through the lenses of intergroup dynamics. In-group identification is one of the most important factors that influence our social & political life. Individuals have an innate tendency to self-categorize into one or more groups.

In attempting to mainitain a positive sense of self, we tend to positively evaluate in-group members and to negatively evaluate out-group members, often exaggerating the differences & thus contributing to (political) polarization. This gap is exploited by many politicians.

Furthermore, identification with the in-group can grow so strongly that membership culminates in feelings of psychological attachment: membership is thus internalized as part of the Self, in what becomes a ‘

social identity (Tajfel and Turner 1979).

social identity (Tajfel and Turner 1979).

The boundaries marking in-group belonging

also separate members from ‘Others’. Hostility

towards out-groups can increase with perceived challenges. Emotions amplify these dynamics, reinforcing internal cohesion & increasing motivation to stand up against challenges to the group.

also separate members from ‘Others’. Hostility

towards out-groups can increase with perceived challenges. Emotions amplify these dynamics, reinforcing internal cohesion & increasing motivation to stand up against challenges to the group.

Emotions are an integral part of the way we navigate the surrounding environment & make relevant decisions; as such they are also vital to any type of political engagement. Affective reactions are automatic: there is no ‘rational’ thinking entirely independent from emotions.

By now you should be realising why populist politicians like, say Trump & Farage, or populist newspapers, like the Sun or Express, deliberately stoke tensions, relentlessly scapegoat, demonize & antagonise: the emotional fall-out galvanises group-identity.

This research, by Donatella Bonansinga, looks at three dimensions: the ‘Structural Dimension’ looks at macro processes & long-term trends that link the role of emotions to support for populism; the ‘Subjective

Dimension’ draws on the political psychology; and the

Dimension’ draws on the political psychology; and the

‘Communicative Dimension’ discusses how emotionality intertwines with populist discourse to address the publics’ affective requests.

Starting with the Structural Dimension then: Political scientists have principally focused on the role played by globalisation processes.

Starting with the Structural Dimension then: Political scientists have principally focused on the role played by globalisation processes.

The progress & advancements associated with globalisation have created a new social cleavage between those who embrace post-materialist values and those who fear the rapid erosion of previously predominant views. Such cleavage has a significant affective underpinning.

It divides citizens whose preferences have increasingly shifted towards ‘progressive issues’, such as cosmopolitanism & multiculturalism & new sexual/gender identities, from those who reject these developments, which they perceive as a form of displacement (he 'culture wars').

Seen through these lenses, the success of the populist radical right has a lot to do with the profoundly emotional issues of identity, attachment & belonging.

This helps us understand existing polarization started some time ago, but unfolding in real time.

This helps us understand existing polarization started some time ago, but unfolding in real time.

Supporters of traditional values, such as the older generations or the less educated, resent & blame the ‘cosmopolitan’ elites for the erosion of their previously predominant views & polarise towards the anti-establishment & conservative appeal of the populist radical right.

Another perspective is the 'the losers of globalisation thesis', linked to the issue of economic decline, which implies economic crisis & unemployment favour the success of populist parties.

Globalisation has affected subjective feelings of grievances & threat perception...

Globalisation has affected subjective feelings of grievances & threat perception...

creating new forms of conflict, not only economic but also cultural & political, that have disproportionately affected certain sectors of society. By increasing economic competition, cultural diversity & political integration, globalisation has produced ‘winners and losers’.

The 'losers' experience economic insecurity, feelings of cultural threat from people with different ethnic or religious backgrounds, & feelings of loss over weakened national autonomy. Populist parties are therefore inherently about the emotional need to address such grievances.

Populist nationalism is profoundly emotional; it speaks to people that have long distrusted political elites, that have felt increasingly economically deprived & sceptical about the ability of their community to survive the fast-pace changes that immigration was bringing in.

The role of insecurities is pivotal here, as these broad feelings of ‘distrust’, ‘destruction’ & ‘deprivation’ can be identified in a series of strong fears & concerns that citizens have developed, respectively, about lack of voice, ethnic change & economic loss.

These processes & grievances are long-term & now deeply rooted, so we should be wary of those analyses that try to pinpoint one single and recent cause.

Successful political parties demonstrate a good understanding of these issues, their emotional responses &possible solutions.

Successful political parties demonstrate a good understanding of these issues, their emotional responses &possible solutions.

In the 'Subjective dimension', globalisation plays a crucial role, because by increasing competition in economic, cultural & political domains it has indeed brought about competition over jobs, cultural & political identities.

Such emphasis on competition - typical of contemporary capitalist and highly individualist advanced societies - pro-duces a sense of anticipated shame in those individuals who fail (or fear of failing) to maintain their status.

Shame signals a potential or expected loss for which individuals blame themselves; it resembles a sense of failure & incapacity, so painful that people divert it from the Self & directs it as anger to Others. This emotional repression & transmutation is called 'ressentiment'.

These 'ontological insecurities' are complex affective states that intertwine in the web of past, present & future, as certain individuals long for the past & a reassuring present, while others fear what is to come.

This may help understand populist success as it foregrounds the subjective meaning that individuals construct & attribute to their life experience, both in the present & as a projected future, rather than to the objective conditions that are said to leave some people ‘behind’.

Indeed, political psychology research has found evidence that subjective perceptions are key and that citizens not only support populists when feeling deprived, but also in times of economic prosperity that they do not want to lose in the future.

Understanding insecurity & the emotions of insecurity is pivotal for developing a comprehensive account of populist success, one that takes into account the fact the audiences are not mere spectators, but appraise and interpret political development differently.

Finally, the 'Communicative dimension' concerns how populist actors communicate with their publics.

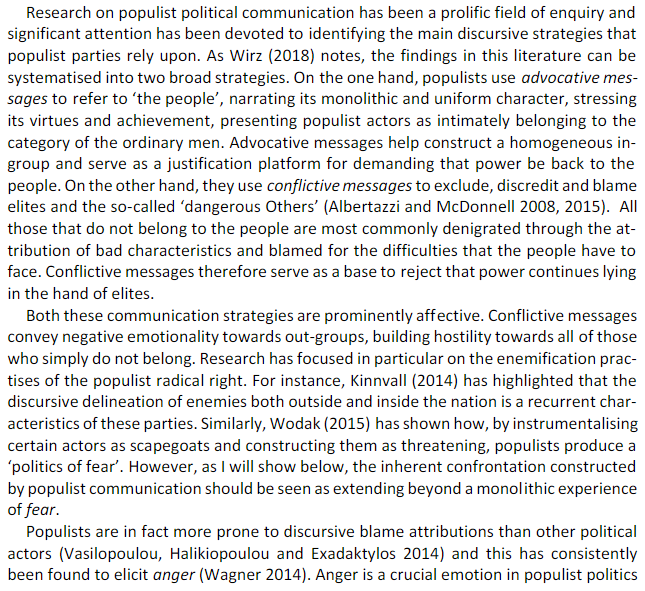

The two main discursive strategies that populist parties rely upon are: (1) advocative messages to

refer to ‘the people’, narrating its monolithic & uniform character.

The two main discursive strategies that populist parties rely upon are: (1) advocative messages to

refer to ‘the people’, narrating its monolithic & uniform character.

Virtues & achievement are stressed, presenting populist actors as belonging to the category of ordinary men & women. Advocative messages help construct a homogeneous in-group & serve as a justification platform for demanding that power be back to the people. "Will of the people".

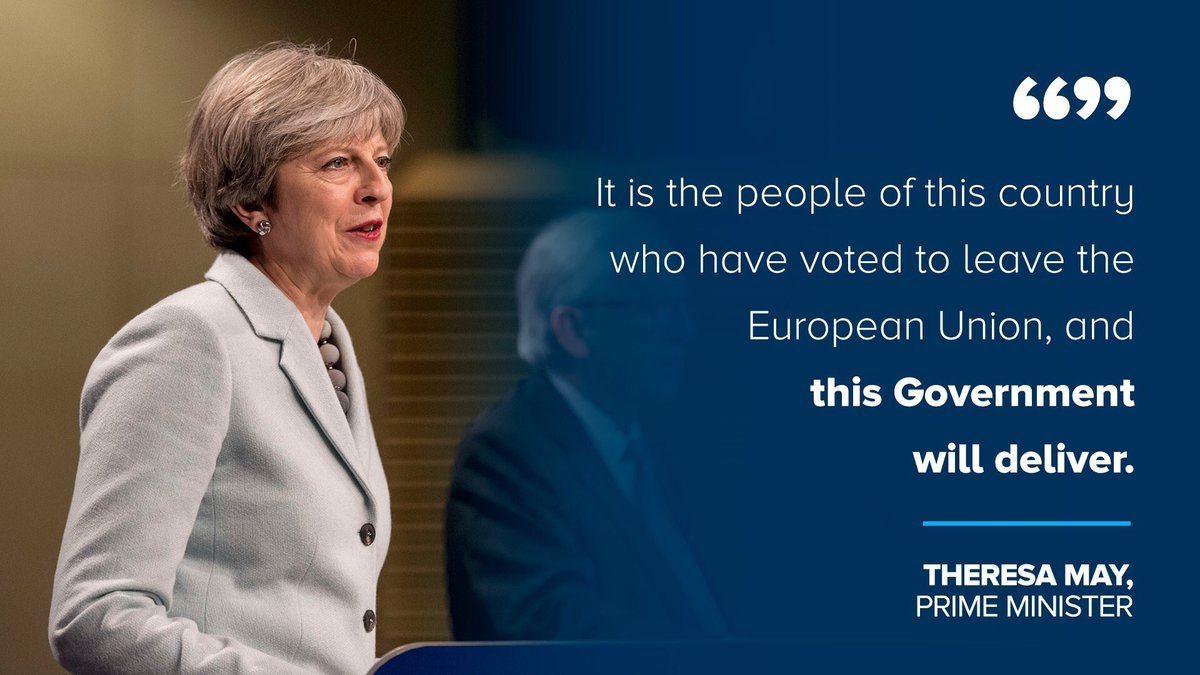

(2) conflictive messages exclude, discredit and blame elites and the so-called ‘dangerous Others’

All those that do not belong to the people are most commonly denigrated through the attribution of bad characteristics & blamed for the difficulties that the people have to face.

All those that do not belong to the people are most commonly denigrated through the attribution of bad characteristics & blamed for the difficulties that the people have to face.

Conflictive messages serve as a base to reject power continuing to be in the hand of 'elites'.

Both these communication strategies are prominently affective (emotional). Populists are more prone to discursive blame attributions, which elicits anger, than other political actors.

Both these communication strategies are prominently affective (emotional). Populists are more prone to discursive blame attributions, which elicits anger, than other political actors.

Right-wing populist rhetoric promotes anger with a discourse that is crafted to “deflect shame-induced anger & hatred away from the self & instead toward the political & cultural establishment and various Others”.

The populist left, on the other hand, acknowledges rather than represses shame, as both its discourse & networked structure foster solidarity & the sharing of grievances.

Hence the charge by the Right of 'grievance culture'.

Hence the charge by the Right of 'grievance culture'.

The Left's social movement culture, based on the ideal of participation, encourages a collaborative sentiment & allows for the transformation of shame “into high-energy, active emotions such as frustration, indignation and anger”.

Nostalgia responds to visions of the contemporary world as disrupted by fast-paced socio-economic change. The populist narrative portrays the inability of the elites to attend, manage or halt such changes, as the principle cause that makes the present a moment of severe danger.

Populist nostalgic appeals tame these feelings by providing the comfort and security of the past imaginary. The bittersweet element of nostalgic emotionality helps us transition to the role of positive affect in populist discourse, which is often sidelined in the literature.

Emotions of anger & fear are complemented by a positive self-construction that harnesses the positive values such as honesty, hard work & ordinariness, which bring 'the people' together. Populists foster a sense of belonging by drawing on the commonality of values & experiences.

Populists build cohesion by highlighting that the people share the common experience of deception & exploitation by self-serving & corrupt elites. There is thus a flow of both positive & negative affect that is directed both in-wards & outwards, toward the people & its enemies.

There is emotional complexity in populist communication; we should not simplify populist rhetoric as a single-emotion politics (eg the politics of fear, or of anger) & rather take into account that different emotional appeals coexist at the same time & within the same narrative.

Visual research has evidenced both the complexity & variety of emotions invoked by populists (especially on the Right). The strategic use of images, such as the controversial electoral posters, allows conveying highly charged messages in a simplified and instant way.

Posters build boundaries between in-groups & out-groups by mobilising, on the one hand, symbols of pride & belonging & appealing to the positive affect generated by one’s identity, & on the other, they construct imaginaries of threat and insecurity, by invoking otherness.

The ‘content’ of the term ‘the people’ has several connotations. First, 'the people' may be intended with a democratic connotation to indicate the ultimate source of power in a democratic regime; hence, the people as the sovereign, the ruler.

Second, the term can be used to refer to an average socioeconomic status, which usually brings together the majority of citizens in a given country; thus the people as ‘the common’ and ‘ordinary’ people.

Finally, the ethno-nationalist connotation appeals to those who are natives of a specific place.

The socio-economic vs nativist connotations constitute an important distinction between inclusionary & exclusionary populists.

The socio-economic vs nativist connotations constitute an important distinction between inclusionary & exclusionary populists.

The latter define the people strictly as natives & thus construct a large number of out-groups, whereas inclusionary populists understand the people more broadly, as those who have been aggrieved by neoliberal elites, regardless of ethnicity, religion or culture.

Right-wing populist rhetoric promotes anger & resentment directed at those who have a “good life” without hard work, such as politicians & top managers on high & secure income, welfare recipients & refugees “looked after by the state,” & the "lazy" long

-term unemployed.

-term unemployed.

Right-wing populists also direct anger at groups perceived to be different from “us”: ethnic, cultural, political, & sexual minorities.

Left-wing rhetoric instills anger at those responsible for enforcing politics perceived to increase injustice, inequality, & precariousness.

Left-wing rhetoric instills anger at those responsible for enforcing politics perceived to increase injustice, inequality, & precariousness.

Populism has long been labelled an ‘emotional’ phenomenon to indicate an opportunistic discourse that manipulates citizens. It's widely rooted in the idea of a clear-cut divide between emotions & reason, which makes decision-making based on the former too ‘fast’ & ‘unreliable’.

But the dichotomy heart versus mind hardly stands up to scientific inquiry. Systematic & compelling evidence now sustains an idea of decision-making as a function that relies conjunctly on emotions AND cognition: emotionality & rationality are intimately related & interdependent.

The role of emotions helps us understand the populist appeal, but not because populism is an ‘emotional’ phenomenon in an ‘unemotional & entirely rational political world': populism is peculiarly emotional & specific affective states contribute to its rise, development & success.

Populists on the left & on the right, have built their deeply affective accounts of who is the danger, who is in danger, & who is to blame, that are crafted to respond to contemporary affective requests. Populist narratives become the lenses through which meaning is con-structed.

Emotions are produced at the macro-level, perceived at the individual level but also guided, shaped & reproduced through political narratives: multi-level analysis helps unpack the significance of emotions for the entire process of populism emergence, diffusion, & success.

The fascinating, important & very timely article 'Who Thinks, Feels: The Relationship Between Emotions, Politics And Populism', was written by @dbonansinga.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter