We re-analysed Seibold et al. 2019’s @nature study on #insect declines in Germany and found that after accounting for temporal pseudoreplication by adding a year random intercept term, 4 of 5 declines became non-significant. More in our #openaccess paper: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/icad.12468

In a multi-site analysis, we found a wide variety of invertebrate trends over time, including declines as reported in Seibold et al. 2019, but we found the most extreme trends for shorter time-series that are more influenced by sampling error.

Year random terms are important to include when there is substantial pseudoreplication of data from each year. In the case of Seibold et al. 2019, there were 150 grassland and 140 forest sites (30 in some analyses) per year. Data from the same year are not independent.

Seibold et al. aim to capture year effects by including environmental variables, but we found that the significant year effects persist both with and without environmental variables in the models. Including a year random term renders most trends non-significant.

Diversity in one year influences the amount of individuals or species in the next. This autocorrelation between consecutive years wasn’t tested by Seibold et al. or us. If autocorrelation were included in models, uncertainty in trend estimates is expected to increase further.

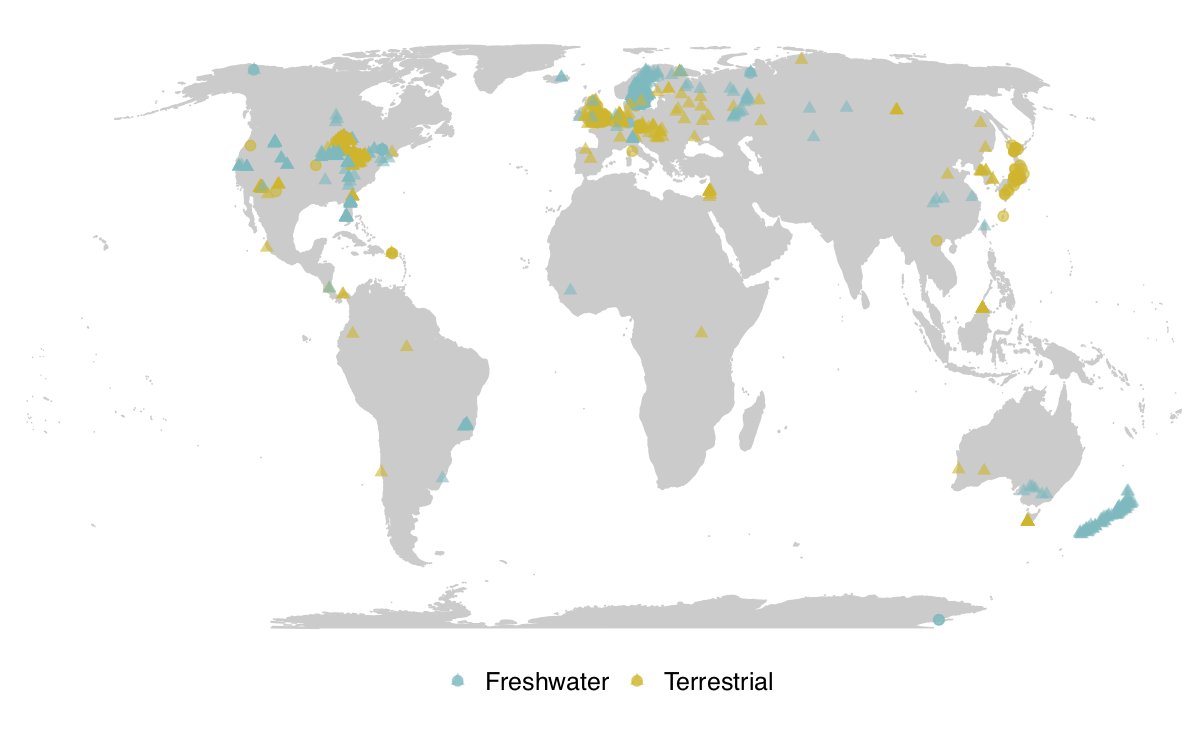

Amid mounting concern about #insect #biodiversity we found that the average trend across published insect diversity time series is not a decline, though we can’t rule out that some taxa in some environments are experiencing precipitous declines. https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/environment-and-conservation/2021/01/insects-are-vanishing-at-an-alarming-rate-but-we-can-save-them

We agree with Seibold et al.’s reply to us that short time series do have tremendous value, but they will be more subject to sampling error. We echo the calls of many others for a global effort to monitor insect trends and fill in the gaps.

Thanks to Seibold et al for engaging with us on this important topic! You can check out the Seibold response to our comment here: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/icad.12467

It is exciting to read the growing literature tracking insect abundance trends. We advocate for careful consideration of not only how insect populations are changing but for how we analyse ecological time series.  : @gndaskalova

: @gndaskalova

: @gndaskalova

: @gndaskalova

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter