Alright, so last time we left off the Allied army under Marlborough and Eugene of Savoy were facing off with a Franco-Bavarian army under Marshal Tallard, Elector Maximilian, and Marsin. In this thread we will be examining the Battle of Blenheim in way too much detail. https://twitter.com/JasonLHughes/status/1349799814167465989

Special thanks to Jeff Berry, who gave me permission to use his excellent maps (the detailed ones with the copyrights). Please go check out his “Obscure Battles” blog using the link below. His post on Blenheim is extremely detailed and very well written. http://obscurebattles.blogspot.com/2013/11/blenheim-1704.html

Also, please don’t use his maps without his permission. He put a lot of effort into creating them. It should also be noted that any images I use in this thread are not my own. It is unfortunately very difficult to give credit to the creators of many of these images.

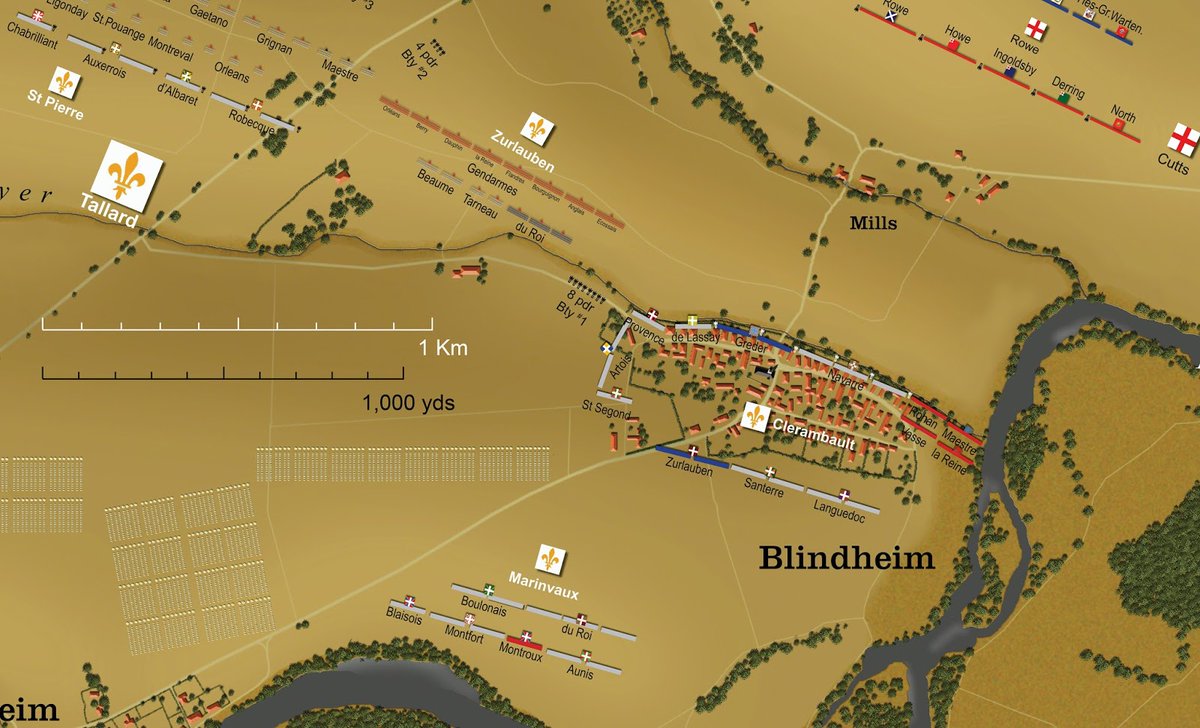

Anyways, we begin this thread on the 12th of August, when Tallard chose to set up camp on the banks of the Nebelbach. The campsite was extremely defendable; the Franco-Bavarian right was anchored by the Danube while the left was anchored by the forested hills of the Swabian jura.

Tallard’s chosen campsite was also adjacent to the villages of Lutzingen, Oberglau, and Blindheim (Blenheim). The position was so strong that the Franco-Bavarian commanders severally doubted the allied army, even with Marlborough’s additional troops, would ever attack it.

Tallard and his fellow commanders predicted Marlborough and Eugene would withdraw towards Nordlingen, but they had no such intentions. Marlborough and Eugene instead drew up a bold (yet loose) plan of attack after reconnoitering the Franco-Bavarian dispositions on the 12th.

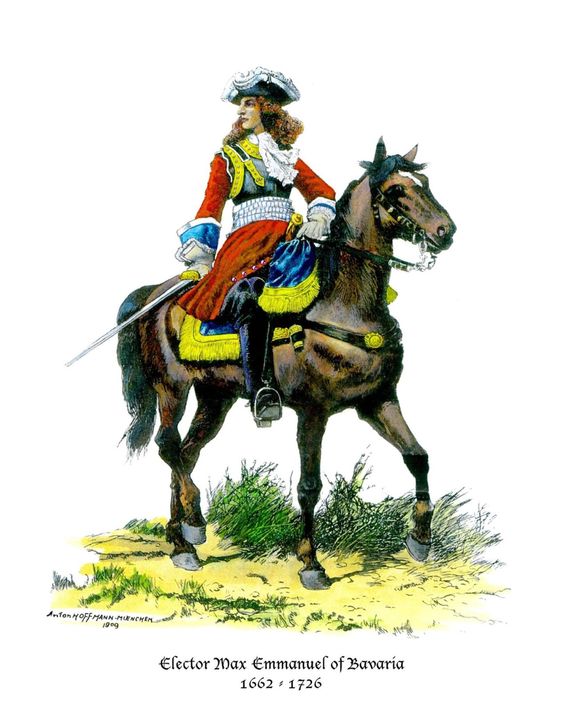

Eugene would lead the Allied right, which had the task to tie down the Franco-Bavarian left (under Maximilian and Marsin). Marlborough would command the bulk of the Allied army and deliver the coup de grâce against the French (under Tallard) holding the Franco-Bavarian right.

While the Franco-Bavarian commanders were surprised to see the Allied army drawing up for battle on the 13th, they were confident in their strong position and the strength of the hitherto undefeated French cavalry. However, there was no grand plan or truly unified command.

The two wings of the Franco-Bavarian army basically acted as two separate armies. There was no central reserve, and units could not easily be moved from one wing to the other. The Franco-Bavarian deployment relied too heavily on the villages and did not form a cohesive line.

Tallard’s general concept was to entice Marlborough to send his troops across the Nebel under withering flanking fire from Oberglau and Blindheim and then get ridden down by the massed French cavalry. Only a few French battalions were stationed behind the French squadrons.

Marlborough almost immediately spotted the weak spot in the French line (as Tallard intended). However, Marlborough believed that his infantry, with their superior discipline and fire drill, could contain the French occupied villages while his cavalry spearheaded a breakthrough.

The Allied army also benefited from the friendship between Marlborough and Eugene; the Allied army would act as a unified whole. All assaults throughout the day were coordinated and both commanders had a clear conception of their objective and that of their colleague.

Long range artillery fire began at around 8:00 in the morning on the 13th. It should be noted that the French and Bavarians had substantially more heavy cannon present on the field, and the Allied army suffered around 2,000 casualties before the infantry even engaged.

Marlborough’s portion of the Allied army was in place by 10:00, with John Cutts’ column securing a few water mills along the Nebel, after which they remained in place and suffered grave casualties to artillery fire. They were waiting on Eugene’s flank to begin its assault.

Eugene’s flank (made up of Austrian, Danish, and Prussian soldiers) was taking more time than anticipated to cross the rough ground near Lutzingen. Eugene’s attack had to start at the same time as Cutts’ attack on Blindheim, otherwise Tallard’s flank would easily be reinforced.

Eugene was supposed to be in place by 11:00, but the extreme roughness of the terrain and the severity of Franco-Bavarian artillery fire delayed his men until noon. Only at 13:00 did the dual attacks on the Franco-Bavarian flanks finally begin.

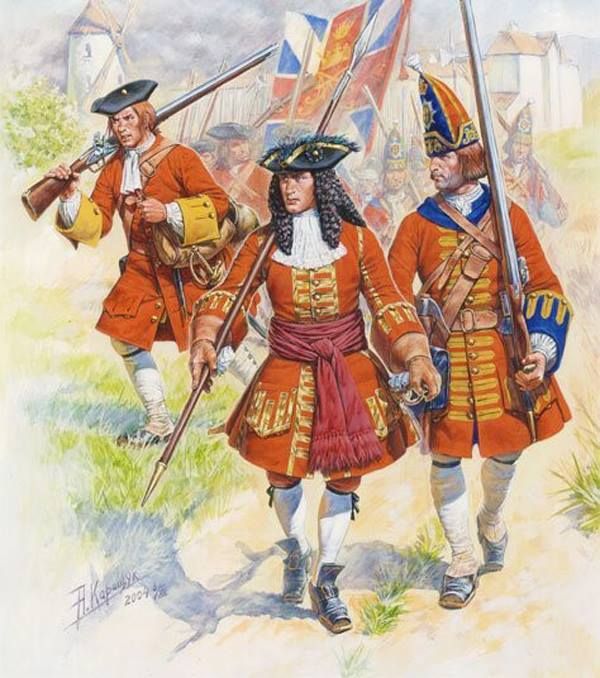

The assault on Blindheim began with Rowe’s brigade rising from the banks of the Nebel and marching the 150 yards to Blindheim in complete silence. The defenders fired a devastating volley at only 30 yards, mortally wounding Rowe before he could order his men to return fire.

Despite many of their officers being cut down in the first volley, the surviving British soldiers closed ranks and charged the palisades defending the village. Some survivors made it over the palisades but were driven back by repeated French volleys. The first assault had failed.

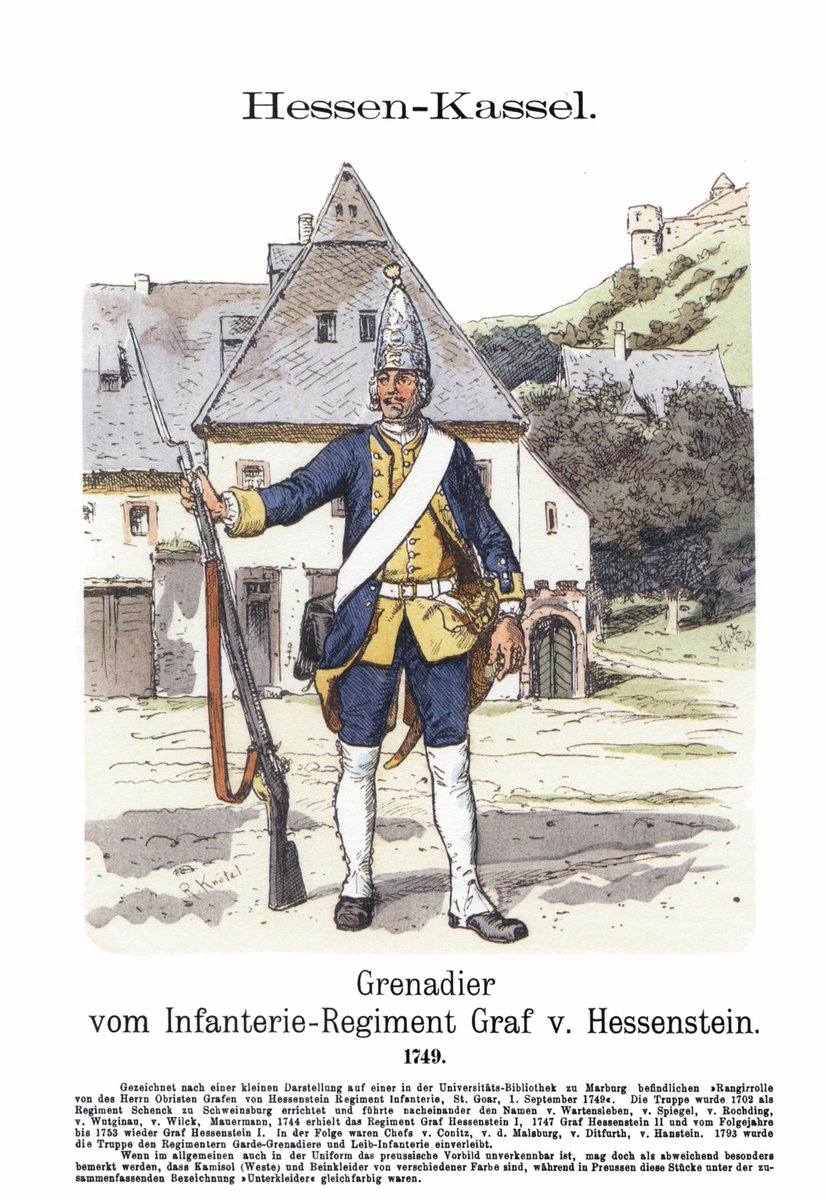

As the attack fell apart, four squadrons of French cavalry fell on the retreating British soldiers, capturing the colours of Rowe’s regiment. The retreating soldiers were only saved by a Hessian brigade, which fired upon the French cavalry on drove them off with a bayonet charge.

Meanwhile, Eugene’s forces were attacking into the superior numbers of the Franco-Bavarian left. The initial attack on Lutzingen was spearheaded by the Leopold of Anhalt Dessau’s Prussians. They went right into the jaws of the Franco-Bavarian position and a murderous crossfire.

The Prussian ranks were swept by Bavarian artillery and musket fire from the front, artillery fire from Oblergauheim, and French musket fire from the tree-line on their right. Nonetheless, the Prussians pushed on, attempting to storm the 16-gun Bavarian battery to their front.

The Danes were doing their best to support their Prussian comrades and clear the tree-line of Frenchmen. Imperial cavalry was forcing its way across the Nebel and making some headway against the French cavalry opposite, thus giving for more and more squadrons to cross.

However, the superior numbers (and elan) of the French cavalry soon overwhelmed the Imperial cavalry and forced them back across the Nebel. With their flanks threatened, the Prussian, and Danish infantry were forced to slowly withdraw across the Nebel.

Various regiments and squadrons began to rout as the Bavarian infantry counterattacked, taking 10 colours from their fleeing enemies. Only the personal intervention of Eugene prevented a catastrophe and the Imperial forces soon reformed near Schwennenbach for another assault.

Meanwhile the remnants of Rowe’s brigade had reformed with the other elements of Cutts’ column and launched a fresh assault on Blindheim. Yet again the assault was repulsed. However, the ferocity of the Anglo-Hessian attack caused the worst French error of the battle. (tbc soon)

Clérambault, the French commander in charge of the defense of Blindheim, panicked during the attack and called in the reserve battalions stationed near the village. Blindheim quickly became overcrowded with well over 10,000 French troops, greatly hampering their fighting ability.

This was the moment Marlborough was waiting for. He ordered Cutts to stop his column’s attack and simply contain the garrison of Blindheim. He then ordered the infantry in his center to rise and begin their march across the Nebel (which had been filled in with fascines).

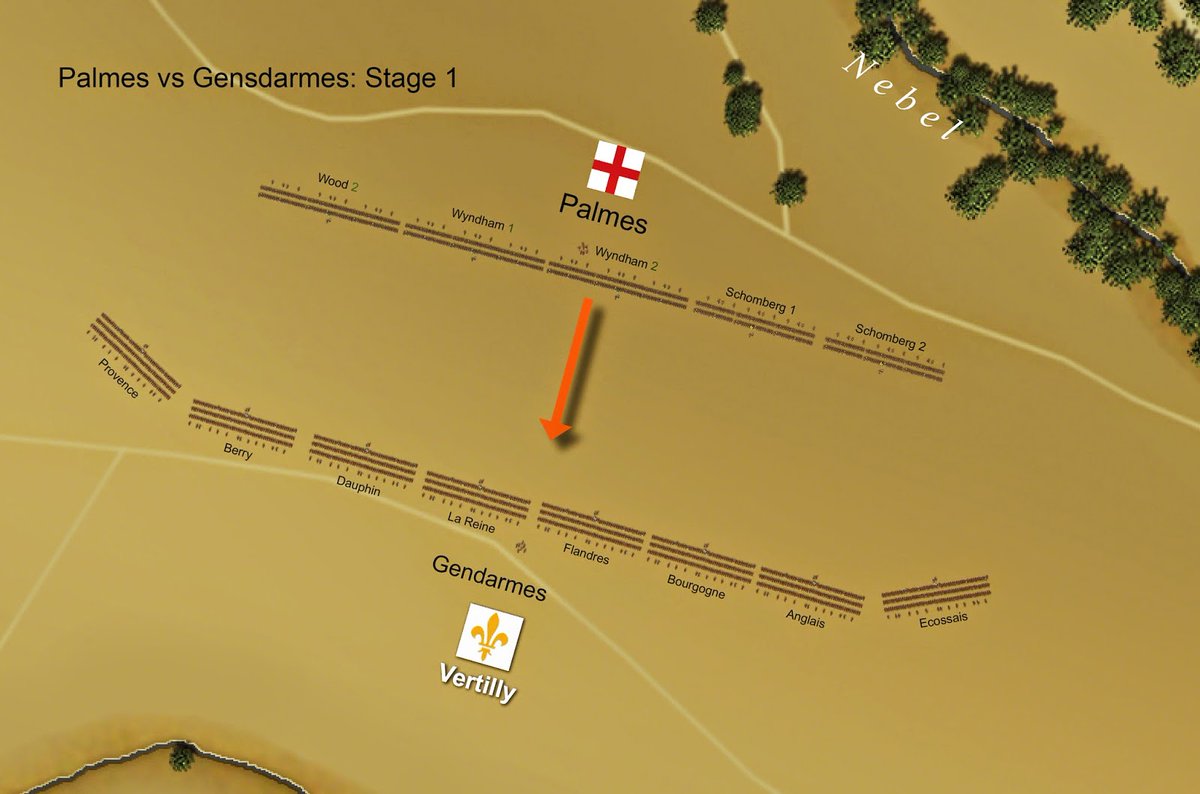

This advance was covered by a small brigade of British dragoons under Colonel Francis Palmes. After crossing the Nebel, Palmes and his 700 troopers were set upon by over twice as many French troopers. And these were not just any cavalry; these were the elite French Gens d’Armes.

As mentioned in my previous threads, the French cavalry were considered the best in Europe before Blenheim. However, the French relied upon pistol fire before closing to the enemy with the arme blanche. Marlborough, however, had introduced new doctrine into the British cavalry.

British cavalry relied solely on the cold steel and charged at their enemy instead of trotting at them like the French cavalry. British cavalry also generally formed up in two ranks (instead of three ranks for the French) to increase the frontage of their squadrons.

These tactical and doctrinal differences were exaggerated by the presence of glanders in many of the horses ridden by Tallard’s cavalry (Marsin’s horses were kept separate and didn’t have glanders). This debilitating disease either weakened or killed many trained French horses.

Thus, when the elite Gens d’Armes of France, the “finest cavalry in Europe,” approached a brigade of mere dragoons, they were in for the greatest (and final) shock of their lives. Their pistol fire did little as the outnumbered British troopers charged into their ranks.

The French line was longer than that of the British dragoons, but it mattered little. Palmes ordered the squadrons on his flanks to separate from the main body and hit the French squadrons that were attempting to outflank him at full speed.

The result was devastating. The French flanks crumbled, and the French center was enveloped while it was still recovering from the British charge from their front. The “gentlemen of France” (to quote a shocked Elector Maximilian) fled before 700 British dragoons.

This fight in and of itself mattered little (Palme’s brigade could not press its advantage), but its psychological impact was massive. Tallard in particular was shaken by the defeat of the gendarmes and Tallard galloped across the field to Marsin to plead for reinforcements.

Tallard’s entire plan relied upon the strength of his cavalry, but it turned out his cavalry was inferior to that of his enemy. While these events transpired, Eugene’s troops had regrouped on the Allied right and launched a second, even more desperate attack on Lutzingen.

Marsin rejected Tallard’s pleas for reinforcements due to this renewed assault. While Tallard was away from his sector, Clérambault brought most of Tallard’s reserves into Blindheim, further overcrowding the village and depriving the French cavalry of vital support.

Some 15,000 troops were contained in Blindheim by Cutts’ mere 5,000 men, who used platoon-fire (see earlier threads for more on that) to drive back several sally attempts. Meanwhile, more and more of Marlborough’s troops were pouring across the Nebel to assault the French center.

It should be noted that Marlborough’s battalions and squadrons were advancing in a fairly novel fashion, with infantry battalions having gaps between them to allow cavalry squadrons to move freely. Unlike the French, Marlborough emphasized combined arms.

The French cavalry, only backed by 9 battalions of infantry, repeatedly advanced upon the Allied forces that had crossed the Nebel but were consistently repulsed with heavy losses. However, the Allied forces were forced to halt their advance due to events near Oberglau.

The garrison of Oberglau presented a major threat to the flank of Marlborough’s advance and had to be neutralized before Marlborough could deliver the coup de grâce. The village was held by 5,000 soldiers, including men from 3 regiments of the already famous Irish Brigade.

At Blenheim these Irishmen would once again prove their courage. Two Dutch brigades attempted to storm the village but were cut down by its defenders. The furious counterattack of France’s finest infantry threatened to blast a hole through the center of the Allied army.

Marsin recognized the opportunity and sent every squadron he could spare to support the Franco-Irish counterattack. This was the last chance of the Franco-Bavarian army for victory, and the men of the Irish Brigade fought ferociously to secure that victory.

Marlborough rushed to the scene and immediately sent in Hanoverian battalions and his reserve of Dutch cavalry to support the remnants of the Dutch brigades. However, the onslaught of French cavalry proved too much, and the Dutch cavalry was steadily being pushed back.

The situation on Eugene’s flank was looking similarly grim. Maximilian, always the soldier, had managed to rally his men against every Allied assault. It was as yet another attack was being repulsed that Eugene received an urgent request for reinforcements from Marlborough.

Eugene sent a brigade of cuirassiers, one of the few reserves Eugene had left, to Marlborough’s aid without hesitation. He knew the battle was going to be won on Marlborough’s side of the field and trusted his judgement. The French commanders showed no such level of cooperation.

The force of around 1,000 cuirassiers thundered towards the flank of Marsin’s cavalry, forcing them to turn away from Marlborough’s infantry to confront the new threat. After a fierce struggle the French cavalry was forced to retire. The Allies had survived the crisis of the day.

Without cavalry support, the French and Irish regiments were forced to retire to Oberglau before superior allied numbers. They had fought bravely, but they would be contained by superior Allied numbers for the rest of the battle and could no longer menace Marlborough’s advance.

After resting his troops for an hour (and allowing Eugene to regroup for a final assault), Marlborough’s attack began anew. Two long lines of Allied cavalry charged forth to crush Tallard’s remaining cavalry. Amazingly, the exhausted French managed to push back the first line.

The courage of the French cavalry could do little against massed infantry fire however, and the second line of Allied squadrons soon entered the fray. The exhausted French cavalry could not withstand the pressure and finally fled before superior numbers.

Tbc in a moment

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter