Few days back the team from NANOGrav made an awesome announcement, up there with my studies & was similar subject to my last major research project for my #AstronomyMasters!

A (very long) thread about pulsars + the Barycentre + gravitational waves coming your way!

A (very long) thread about pulsars + the Barycentre + gravitational waves coming your way!

So, to begin, let me start by sharing this absolutely fantastic, balanced article by @riding_red about the announcement .... it's such a great article, and my supervisor from my last subject is quoted in there too! https://www.sciencealert.com/we-may-have-just-caught-the-first-hint-of-the-background-hum-of-the-universe

Some upfront stuff (cause Lord knows you need it on this site in 2021):

- Not representing views of anyone here, just my own research project for Uni

- If I make a mistake, feel free to let me know, i'm still learning this stuff

- Long thread, so mute #PulsarSSB if you want now

- Not representing views of anyone here, just my own research project for Uni

- If I make a mistake, feel free to let me know, i'm still learning this stuff

- Long thread, so mute #PulsarSSB if you want now

As a recap, let's look at pulsars to begin with ...

Compact remnant objects are formed when massive stars end their lives.

For simplicity, let's consider three different outcomes/scenarios ... all of which are dependent on the progenitor star's mass

#PulsarSSB

Compact remnant objects are formed when massive stars end their lives.

For simplicity, let's consider three different outcomes/scenarios ... all of which are dependent on the progenitor star's mass

#PulsarSSB

In the 1st scenario, when the progenitor star's mass is between about 1 - 8 solar masses, the star will puff off/eject its outer layers leaving its hot cinder core, which is about the size of Earth.

This one is called a White Dwarf.

#PulsarSSB

This one is called a White Dwarf.

#PulsarSSB

Thanks to Pauli Exclusion Principle (1925), these planet-sized stars can't collapse any further because the degeneracy pressure from electrons halts this ... but only to a certain mass upper limit of 1.44 solar masses.

This is known as the Chandrasekhar Limit (1931)

#PulsarSSB

This is known as the Chandrasekhar Limit (1931)

#PulsarSSB

When the mass of the progenitor is larger (roughly 8 - 20 solar masses), there is enough gravitational force to overcome the Chandrasekhar Limit and keep pushing the remnant material together until it reaches the neutron degeneracy limit.

A neutron star is born!

#PulsarSSB

A neutron star is born!

#PulsarSSB

The neutrons are created in the violent collapse when electrons and protons are forced together in high pressures and temperatures (and an electron neutrino is emitted too).

This also has an upper mass constrain known as the TOV limit and is about ~2-3 solar masses.

#PulsarSSB

This also has an upper mass constrain known as the TOV limit and is about ~2-3 solar masses.

#PulsarSSB

And in the last scenario, where the progenitor is ~20+ solar masses, the collapsing mass keeps going past the TOV limit, falling below the Schwarzschild radius (1916) and the remnant object becomes a black hole.

But that's another thread ....

#PulsarSSB

But that's another thread ....

#PulsarSSB

So in summary, an overly simplified model of compact remnant objects based on the rough mass of the collapsing progenitor star:

1 - 8 solar masses = White Dwarf

8 - 20 solar masses = Neutron Star

20+ solar masses = Black Hole

So where do pulsars fit in?

#PulsarSSB

1 - 8 solar masses = White Dwarf

8 - 20 solar masses = Neutron Star

20+ solar masses = Black Hole

So where do pulsars fit in?

#PulsarSSB

That middle level! Pulsars are neutron stars rotating fast enough to enable electromagnetic emissions (such as radio pulses from its poles).

These beams sweep past the Earth like a light house, and we see them 'pulse' at regular intervals.

Hence "pulsars"!

#PulsarSSB

These beams sweep past the Earth like a light house, and we see them 'pulse' at regular intervals.

Hence "pulsars"!

#PulsarSSB

Pulsars are really cool and given us many firsts/insights:

- First Indirect gravitational waves (1974)

- First Exoplanets (1992)

- Lots of General Relativity tests

- State of matter under extreme conditions

- Masses in our Solar System

- other really cool shit

#PulsarSSB

- First Indirect gravitational waves (1974)

- First Exoplanets (1992)

- Lots of General Relativity tests

- State of matter under extreme conditions

- Masses in our Solar System

- other really cool shit

#PulsarSSB

Pulsars also come in varieties ... two main categories are isolated (loners) and binaries (frens!).

Some are really magnetic (Magnetars), some steal matter off their frens and speed up lots (millisecond pulsars) and some even destroy their frienemies (Widows).

#PulsarSSB

Some are really magnetic (Magnetars), some steal matter off their frens and speed up lots (millisecond pulsars) and some even destroy their frienemies (Widows).

#PulsarSSB

The slowest spinning pulsar rotates once every 23.5 seconds (Tan et al. 2018) and the fastest 716 times per second, which is ~24% the speed of light! (Hessels et al. 2006).

The enormous magnetic field strengths also vary amongst pulsars from ~10^8 to 10^12 gauss (!)

#PulsarSSB

The enormous magnetic field strengths also vary amongst pulsars from ~10^8 to 10^12 gauss (!)

#PulsarSSB

Pulsars also give off EM energy (not just radio) from two different regions: the polar region and the outer magnetosphere gaps.

All this energy leaving this system does something to the pulsar ..... it slows down their spin rate! (also through particle wind)

#PulsarSSB

All this energy leaving this system does something to the pulsar ..... it slows down their spin rate! (also through particle wind)

#PulsarSSB

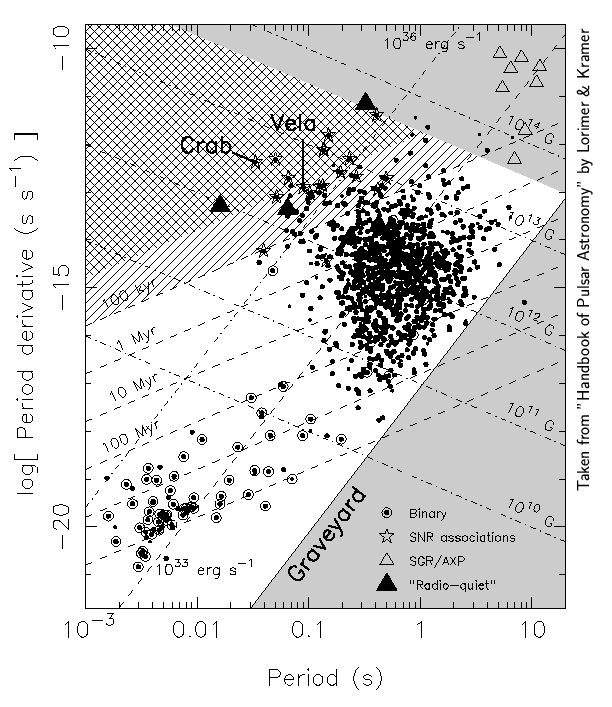

This is really useful to know because it can help paint a picture of the pulsars evolution over time.

The spin-down period derivative is known as "P-Dot" and can be measured extremely accurately. If you measure P-Dot across all pulsars, familiar elements emerge.

#PulsarSSB

The spin-down period derivative is known as "P-Dot" and can be measured extremely accurately. If you measure P-Dot across all pulsars, familiar elements emerge.

#PulsarSSB

Like as pulsars get older, they start to spin slower due to energy loss through magnetic dipole radiation.

Eventually, the magnetic field strength reduces over time, and the 'pulsing' shuts off.

Did the pulsar then die???

#PulsarSSB

Eventually, the magnetic field strength reduces over time, and the 'pulsing' shuts off.

Did the pulsar then die???

#PulsarSSB

So something interesting happens here when we plot some particular parameters ... below a certain point, there are no pulsars found!

It's the infamous 'pulsar graveyard'! (they're still there, just not spinning fast enough to emit)

#PulsarSSB

It's the infamous 'pulsar graveyard'! (they're still there, just not spinning fast enough to emit)

#PulsarSSB

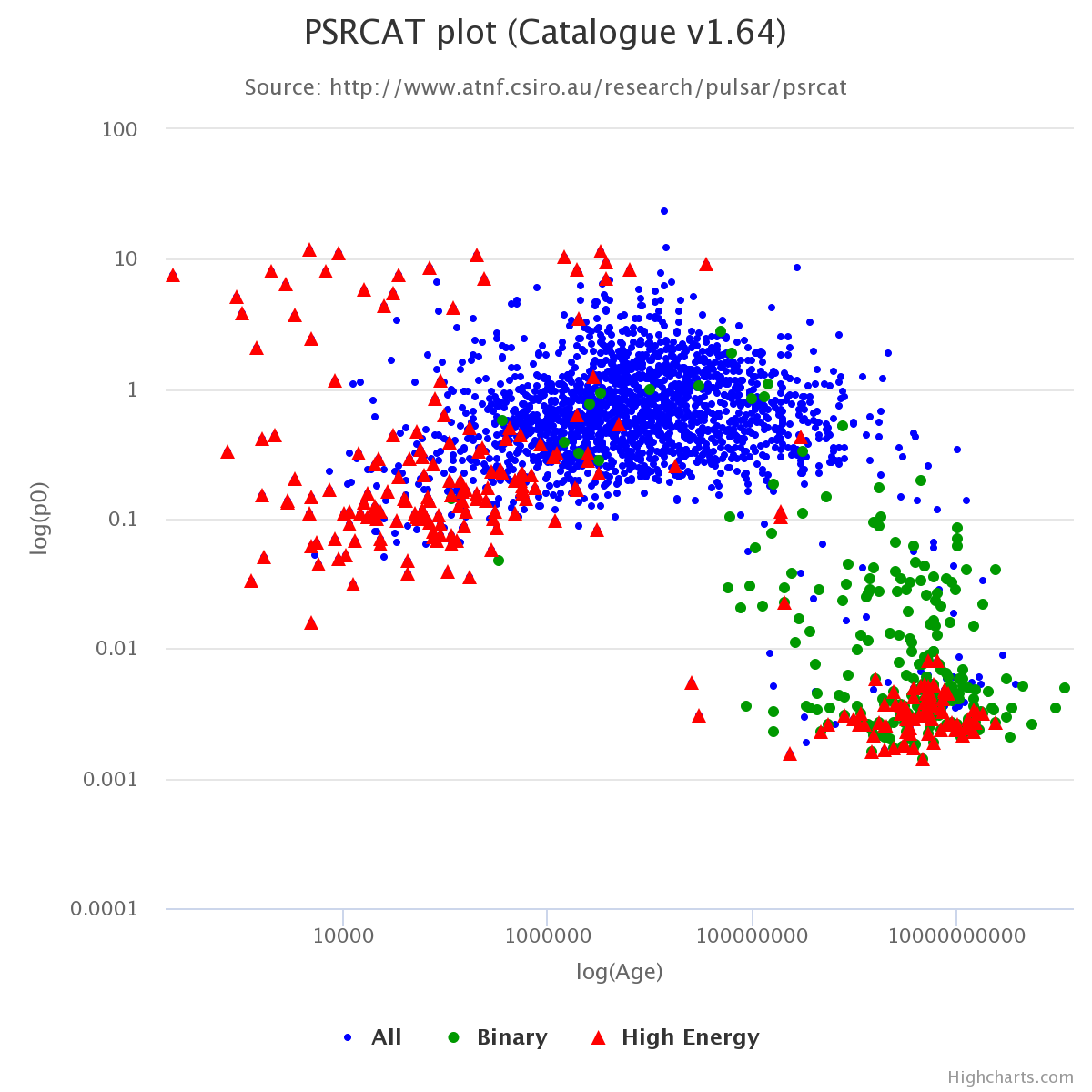

But something else jumps out at us in these plots .... there is a family of pulsars which are older but are spinning very, very fast (wait - shouldn't they have slowed down?!)

And a lot of them also seem to be in a binary pair system!

#PulsarSSB

CSIRO ATNF PSRCAT

CSIRO ATNF PSRCAT

And a lot of them also seem to be in a binary pair system!

#PulsarSSB

CSIRO ATNF PSRCAT

CSIRO ATNF PSRCAT

What in Sol's name could be going on here?!

Well, the pulsar has been a bit greedy and stolen matter from its companion. As this matter falls onto its surface it spins it up, which in turn re-ignites the emissions.

A millisecond pulsar is born!

#PulsarSSB

Well, the pulsar has been a bit greedy and stolen matter from its companion. As this matter falls onto its surface it spins it up, which in turn re-ignites the emissions.

A millisecond pulsar is born!

#PulsarSSB

When you think about it, millisecond pulsars are like a double zombie.

First, the progenitor star dies and they come back to life then.

Then the pulse emissions die, and they STILL come back to life.

It's my next movie plot: World War P (pulsars) .

.

#PulsarSSB

First, the progenitor star dies and they come back to life then.

Then the pulse emissions die, and they STILL come back to life.

It's my next movie plot: World War P (pulsars)

.

. #PulsarSSB

Millisecond pulsars are spinning many times per second, some 100s of times p/s, hence the name.

Fun calculation: pick a spin rate between 100 – 700 rps. Then use 2*pi*radius (default to 10km) x spin rate you picked to work out how fast the pulsar spins in km/s!

#PulsarSSB

Fun calculation: pick a spin rate between 100 – 700 rps. Then use 2*pi*radius (default to 10km) x spin rate you picked to work out how fast the pulsar spins in km/s!

#PulsarSSB

Because of their fast spin rate, millisecond pulsars have stable short periods (and spin-down rates, min. starquakes, etc.) and as such, this makes them better tools to use in pulsar timing methods as probes for lots of astrophysical phenomena.

#PulsarSSB

#PulsarSSB

Long term observations and timing of millisecond pulsars (and their signal arrival time) that are spread across the galaxy is known as a Pulsar Timing Array (PTA), and there are several teams across the world doing this, such as NANOGrav and the Parkes PTA project.

#PulsarSSB

#PulsarSSB

By studying the correlation of data across these millisecond pulsars (MSPs) over long periods, you can do some really, really cool things - like build a Galaxy-scale GPS, or find unknown planets in our system .... or detect of low-freq. stochastic gravitational waves

#PulsarSSB

#PulsarSSB

And here is where we come to this new paper ....

Can correlated timing signals from fast-spinning MSPs peppered around our Galaxy be used to detect low-freq. stochastic gravitational waves generated by in-spiral massive objects like supermassive black holes?

#PulsarSSB

Can correlated timing signals from fast-spinning MSPs peppered around our Galaxy be used to detect low-freq. stochastic gravitational waves generated by in-spiral massive objects like supermassive black holes?

#PulsarSSB

Quick, very high-level summary on gravitational waves, and in particular the different kinds of objects that produce them (not inclusive of everything but more a top-level summary, as that is an entire thread in itself)

#PulsarSSB

#PulsarSSB

Gravitational Waves (GWs) are distortions in space-time caused by accelerating masses. They were an outcome of Einstein's General Relativity back in 1916, indirectly observed and reported by 1974, and directly detected by LIGO in 2015.

#PulsarSSB

#PulsarSSB

There are many objects that emit GWs (including you doing squats!) but these distortions are so feeble, that they can be discarded.

However, astrophysical objects with HUGE MASSES, like neutron stars, black holes and supermassive black holes will shake things up!

#PulsarSSB

However, astrophysical objects with HUGE MASSES, like neutron stars, black holes and supermassive black holes will shake things up!

#PulsarSSB

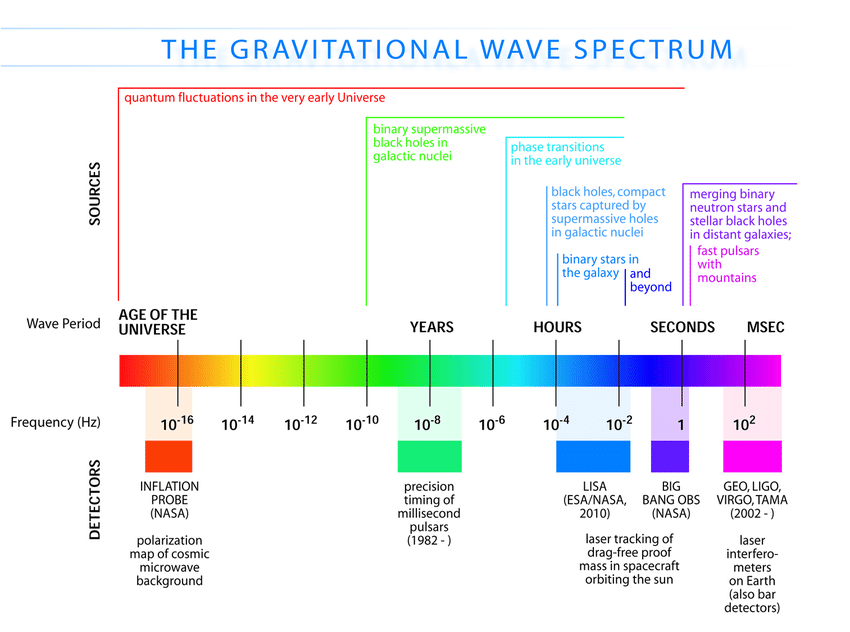

Because of this, GWs come in a range of frequencies (a spectrum) and different types of detectors are built (or will be) to tap into these different frequencies.

For example, LIGO/Virgo tunes into merging stellar mass black holes and neutron stars.

#PulsarSSB

Uni Glasgow

Uni Glasgow

For example, LIGO/Virgo tunes into merging stellar mass black holes and neutron stars.

#PulsarSSB

Uni Glasgow

Uni Glasgow

Pulsar Timing Arrays (PTAs) tune into lower frequency background GWs, with these wavelengths that last years (hence, PTA projects need to use long-spanning data)

These GWs are created by the in-spiral of supermassive black holes, in the hearts of colliding galaxies.

#PulsarSSB

These GWs are created by the in-spiral of supermassive black holes, in the hearts of colliding galaxies.

#PulsarSSB

So how can in-spiral supermassive black holes get to gravitational waves using pulsars?

Well, a single pulsar can't do it alone, but if there is a correlated signal across an array of pulsars - then this might mean a detection has taken place.

#PulsarSSB

Well, a single pulsar can't do it alone, but if there is a correlated signal across an array of pulsars - then this might mean a detection has taken place.

#PulsarSSB

But it is not that simple ...

Consider this: our observatories are on Earth's surface which are used to measure the signals received from pulsars are moving with reference to Earth's axis and also as Earth orbits the Sun.

Lots of dynamic movement!

#PulsarSSB

Consider this: our observatories are on Earth's surface which are used to measure the signals received from pulsars are moving with reference to Earth's axis and also as Earth orbits the Sun.

Lots of dynamic movement!

#PulsarSSB

To get around this, we need to convert the signal received on Earth, to that of an inertial frame of reference - the central mass point of our Solar System .... the Solar System Barycentre! (SSB)

But again, it’s not that easy as all the masses tug on the SSB.

#PulsarSSB

But again, it’s not that easy as all the masses tug on the SSB.

#PulsarSSB

Given the ultra-deep sensitivity required to detect correlated signals from stochastic GWs, signal delays (e.g. atmospheric, Einstein, Shapiro, Roemer, dispersion) all need to be considered, as does orbital motion of binary systems. Not to mention clock corrections.

#PulsarSSB

#PulsarSSB

We also need to account for noise sources, such as white noise (e.g. physical noise sources in the PTA data) and red noise (e.g. timing noise, irregularities produced by events on the pulsar, variations in dispersion measure, Solar System ephemeris variations).

#PulsarSSB

#PulsarSSB

Do you know what else can look like red noise? ....

An observed signal produced by the gravitational wave background of in-spiral supermassive black hole binaries ... the thing that everyone is looking for!

#PulsarSSB

An observed signal produced by the gravitational wave background of in-spiral supermassive black hole binaries ... the thing that everyone is looking for!

#PulsarSSB

When combined with the deep sensitivity of PTA experiments, it is the reason why all teams are working hard to ensure they are isolating all discrepancies, noise sources, errors in ephemeris, etc.

#PulsarSSB

#PulsarSSB

Something very cool that excites me about this project (and the focus of my #AstronomyMasters research assignment) is what PTAs can tell us about our own Solar System.

Info about the SSB, or even if a Planet Nine exists in the far outer reaches by using pulsars (!!)

#PulsarSSB

Info about the SSB, or even if a Planet Nine exists in the far outer reaches by using pulsars (!!)

#PulsarSSB

HOW????

(thought you'd never ask ....)

Well, remember how I mentioned that pulsar timing signals are measured with the SSB internal frame of reference .... well, all the planets in our system exert an influence on the SSB that can be detected in pulsar data!

#PulsarSSB

(thought you'd never ask ....)

Well, remember how I mentioned that pulsar timing signals are measured with the SSB internal frame of reference .... well, all the planets in our system exert an influence on the SSB that can be detected in pulsar data!

#PulsarSSB

Most of the 'influence' on the SSB is caused by the 4 largest planets, & Jupiter's mass and distance even drops the SSB just outside the solar surface.

Jove moves the Sun by ~ 12 m/s!

So the Sun + Jupiter dance around a point 1.07 solar radii from the Sun's centre.

#PulsarSSB

Jove moves the Sun by ~ 12 m/s!

So the Sun + Jupiter dance around a point 1.07 solar radii from the Sun's centre.

#PulsarSSB

Saturn also moves the Sun, but by a much smaller amount of 2.8 m/s. When looking at the SSB between in the Sun-Saturn system, it is within the Sun's surface, but still not it's centre.

So even Saturn causes the Sun to dance around a bit.

#PulsarSSB

So even Saturn causes the Sun to dance around a bit.

#PulsarSSB

The Ice Giants also have enough mass and distance to shift the SSB away from the exact centre of the Sun, but these become rather smaller.

Interestingly, Neptune - though it is further - exerts a greater force on the SSB than Uranus, due to its higher mass.

#PulsarSSB

Interestingly, Neptune - though it is further - exerts a greater force on the SSB than Uranus, due to its higher mass.

#PulsarSSB

Which then takes us to hypothetical Planet Nine.

Based on its predicted size/distance ranges, it should also exhibit an influence on the SSB, but AFAIK none has ever been observed.

And PTAs are fairly accurate - have measured Gas/Ice Giants mass to many decimals!

#PulsarSSB

Based on its predicted size/distance ranges, it should also exhibit an influence on the SSB, but AFAIK none has ever been observed.

And PTAs are fairly accurate - have measured Gas/Ice Giants mass to many decimals!

#PulsarSSB

Now before anyone starts going off at me, just know that I am not saying Planet Nine is NOT there based solely on PTA data ... my view of why it is not there incorporates about 10 different methods/studies which I researched.

BUT - I hope I am wrong and it is there!

#PulsarSSB

BUT - I hope I am wrong and it is there!

#PulsarSSB

Back to how the SSB is calculated using Pulsar timing signals ...

This has to do with something called the Roemer correction (R_ob), and involves the pulsar's lat/long (or RA/Dec), and a vector distance that describes the observer's position to the SSB.

#PulsarSSB

This has to do with something called the Roemer correction (R_ob), and involves the pulsar's lat/long (or RA/Dec), and a vector distance that describes the observer's position to the SSB.

#PulsarSSB

R_ob itself is made up of smaller components:

Distance between observer + the Earth's centre (R_oe)

Distance between centre of the Earth-Moon barycentre to the centre of the Sun (R_es)

Distance capturing the distance of the centre of the Sun to the SSB (R_sb)

#PulsarSSB

Distance between observer + the Earth's centre (R_oe)

Distance between centre of the Earth-Moon barycentre to the centre of the Sun (R_es)

Distance capturing the distance of the centre of the Sun to the SSB (R_sb)

#PulsarSSB

One of the key elements of data in these inputs is the Solar System ephemeris which are generated by folks like NASA JPL.

The JPL ephemeris are the default used, and we know they are accurate to high degree because they land robots on other worlds successfully!

#PulsarSSB

The JPL ephemeris are the default used, and we know they are accurate to high degree because they land robots on other worlds successfully!

#PulsarSSB

Ephemeris are usually generated for space missions, and are continually changing to incorporate new data from in-situ and remote sensing observations.

So things can start to get tricky here ... one must ask, which set is best to use to plug into SSB calcs?

#PulsarSSB

So things can start to get tricky here ... one must ask, which set is best to use to plug into SSB calcs?

#PulsarSSB

There's something beautiful about this topic from a "WOW, humans do amazing things" angle ...

In that probes out at the planets measure mass, gravity, orbits, etc. and feedback into this system. The more accurate the feedback, the better the SSB calc quality.

#PulsarSSB

In that probes out at the planets measure mass, gravity, orbits, etc. and feedback into this system. The more accurate the feedback, the better the SSB calc quality.

#PulsarSSB

A high-level example ... spacecraft that have been to Mars have measured perturbations in its orbit, which in turn has helped define the mass of the Asteroid belt (along with other methods).

That's how detailed this is .... which kinda blows my mind!

#PulsarSSB

That's how detailed this is .... which kinda blows my mind!

#PulsarSSB

So which ephemeris should we choose?

It's not as easy as just picking the latest - they don't build on the previous sets chronologically ... each new ephemeris is dedicated to a new mission, and might leave out various important data.

#PulsarSSB

It's not as easy as just picking the latest - they don't build on the previous sets chronologically ... each new ephemeris is dedicated to a new mission, and might leave out various important data.

#PulsarSSB

A very loose example, the DE421 data for Saturn was more accurate because it incorporated Cassini's mission in-situ observations, where another version would use Juno's in-situ observations of Jupiter more accurately.

#PulsarSSB

#PulsarSSB

This discrepancy issue within the ephemeris data sets has been known for sometime (Proszynski 1984) with more recent analysis supporting this position (Caballero et al. 2018, Arzoumanian et al. 2018, Goncharov et al. 2020).

#PulsarSSB

#PulsarSSB

So my little #AstronomyMasters research project was to check out the JPL data sets and analyse their changes over time, and then use pulsar signals to see if I could note any patterns that could rule in or out better-favoured ephemeris to use for PTA objectives.

#PulsarSSB

#PulsarSSB

It was actually a really fun project, and I got to speak directly to folks at JPL as well (who helped greatly).

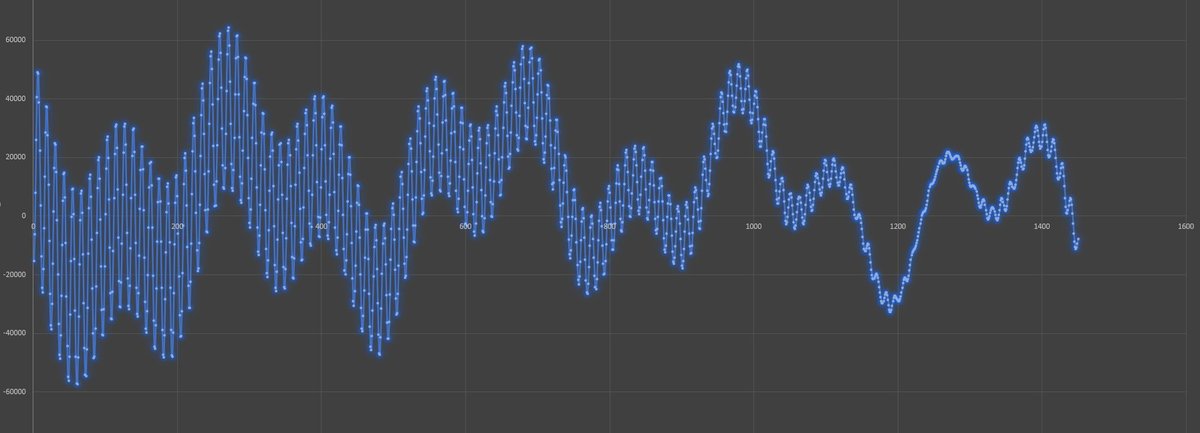

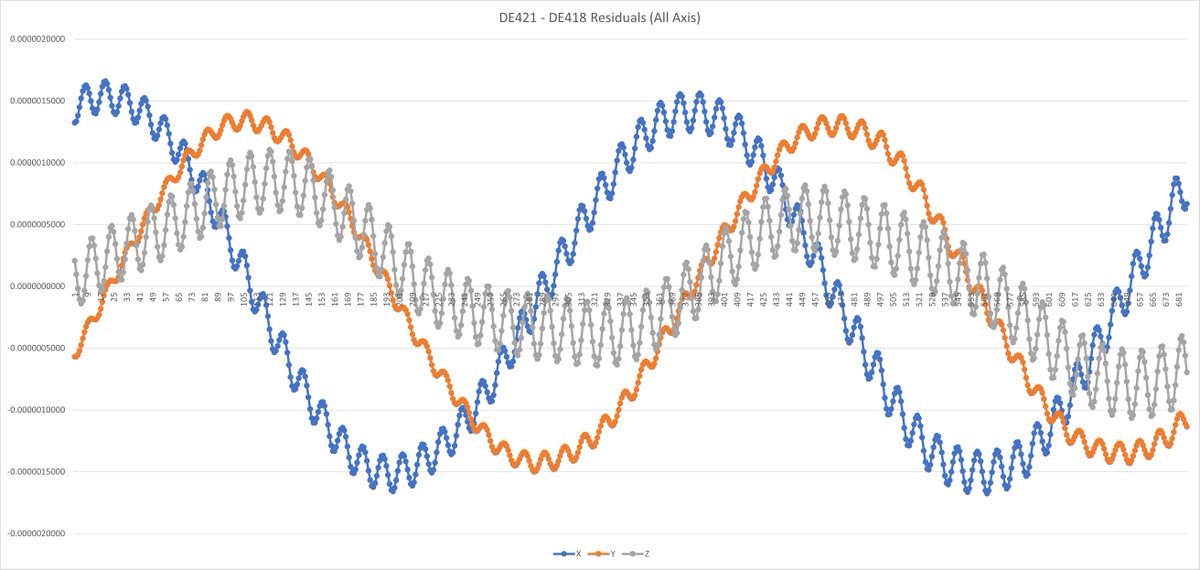

Check this out: here's a (very bad) plot I made in Excel from the SSB data I extracted from the JPL Horizons service (default to DE421)

#PulsarSSB

Check this out: here's a (very bad) plot I made in Excel from the SSB data I extracted from the JPL Horizons service (default to DE421)

#PulsarSSB

Some explainers:

X-axis is a time range, spanning monthly data points between 01/01/1900 - 31/12/2020 (120 years)

Y axis represents the z-value cartesian coordinate of Earth in its orbit, i.e. 0 is the equatorial plane and +/- is in kms.

#PulsarSSB

X-axis is a time range, spanning monthly data points between 01/01/1900 - 31/12/2020 (120 years)

Y axis represents the z-value cartesian coordinate of Earth in its orbit, i.e. 0 is the equatorial plane and +/- is in kms.

#PulsarSSB

Note some cool stuff happening here ....

Every individual wavelength (crest to crest) is 12 months, or Earth's orbit.

See what happens every 12 and roughly 30 peaks? That's Jupiter and Saturn's influence on Earth bopping above and below the ecliptic in its orbit.

#PulsarSSB

Every individual wavelength (crest to crest) is 12 months, or Earth's orbit.

See what happens every 12 and roughly 30 peaks? That's Jupiter and Saturn's influence on Earth bopping above and below the ecliptic in its orbit.

#PulsarSSB

So that bad plot (and yes, this is Excel and I am not ashamed!) was just a test for me to play around with the data (not even sure I did things correctly) but it involved only SSB data from JPL and no pulsar data.

The fun part was doing this INCLUDING pulsar data!

#PulsarSSB

The fun part was doing this INCLUDING pulsar data!

#PulsarSSB

So i ran my sims using a bright pulsar to observe the time of arrivals of signals, but across different ephemeris and then determined the difference between sets to find residuals, that I could plot.

And the variances were big between the older sets and new ones!

#PulsarSSB

And the variances were big between the older sets and new ones!

#PulsarSSB

Some cool stuff started popping out again, like Jupiter and Saturn's orbits too ....

Which was another thing that blew my mind ... here I was looking at radio pulses from a distant compact object, and I can clearly see orbital patterns of Solar System planets!

#PulsarSSB

Which was another thing that blew my mind ... here I was looking at radio pulses from a distant compact object, and I can clearly see orbital patterns of Solar System planets!

#PulsarSSB

So based on my #AstronomyMasters research project, I came to the conclusion that selected ephemeris will change the red noise value (big time) AND that I think we might need to await data from across a full Saturnian orbit to be able to finally say that GWs found.

#PulsarSSB

#PulsarSSB

That's just my very junior, 2nd year Master's student opinion though - and I very much have LOTS MORE to learn about this stuff ... of which I am doing along the way through my Uni work.

And am really loving it (as you can probably tell by now ...)

#PulsarSSB

And am really loving it (as you can probably tell by now ...)

#PulsarSSB

So all of this leads back (after my Uni project tangent) to that nice new paper from the NANOGrav PTA team ...

Which as explained in @riding_red article really well ... read it here: https://www.sciencealert.com/we-may-have-just-caught-the-first-hint-of-the-background-hum-of-the-universe and keep your eye out for PTA project papers!

#PulsarSSB

Which as explained in @riding_red article really well ... read it here: https://www.sciencealert.com/we-may-have-just-caught-the-first-hint-of-the-background-hum-of-the-universe and keep your eye out for PTA project papers!

#PulsarSSB

Ending this mega-thread .. so thanks to everyone who stuck around, liked, shared, commented and didn't mute me along the way!

Pulsars are COOL AF and that is the hill I am going to die on.

/end

#PulsarSSB

Pulsars are COOL AF and that is the hill I am going to die on.

/end

#PulsarSSB

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter