Really proud to finally share some more findings from my PhD, now published open access in @JAMAPsych Buckle up  for a tweetorial of the main points to get you started.. https://twitter.com/JAMAPsych/status/1349400845964734468

for a tweetorial of the main points to get you started.. https://twitter.com/JAMAPsych/status/1349400845964734468

for a tweetorial of the main points to get you started.. https://twitter.com/JAMAPsych/status/1349400845964734468

for a tweetorial of the main points to get you started.. https://twitter.com/JAMAPsych/status/1349400845964734468

People who have depression or psychosis are more likely than the general population to have physical health problems like diabetes and obesity.

Traditionally, the received wisdom has been that the physical health problems occur secondary to the mental disorder, due to things like lifestyle factors

, healthcare inequalities

, healthcare inequalities  and/or the side effects of medications

and/or the side effects of medications  used to treat those mental disorders.

used to treat those mental disorders.

, healthcare inequalities

, healthcare inequalities  and/or the side effects of medications

and/or the side effects of medications  used to treat those mental disorders.

used to treat those mental disorders.

These factors are really important, and remain crucial malleable targets to reduce the impact of physical health burden in people with mental health disorders  .

.

.

.

But, because lots of previous research has been cross-sectional, and/or included people who already have a psychiatric diagnosis, it’s hard to disentangle the direction of association (e.g., what comes first, disruption to physical health or disruption to mental health)

Also, previous research has mostly included single point measurements of cardiometabolic markers, yet repeat measures of these markers provide much greater resolution into potential underlying biological pathways

.

.

.

.

So, we used the fantastically rich and comprehensive ALSPAC resource @CO90s to try and address those limitations.

We wanted to know whether trends in insulin levels or BMI over time from childhood might be associated with an increased risk of psychosis or depression in adulthood, after taking into account a host of other possible explanatory factors (confounders).

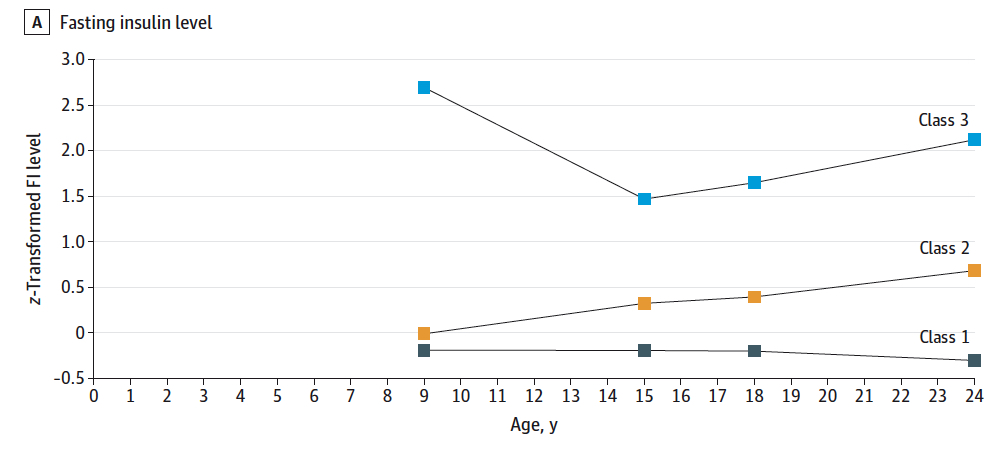

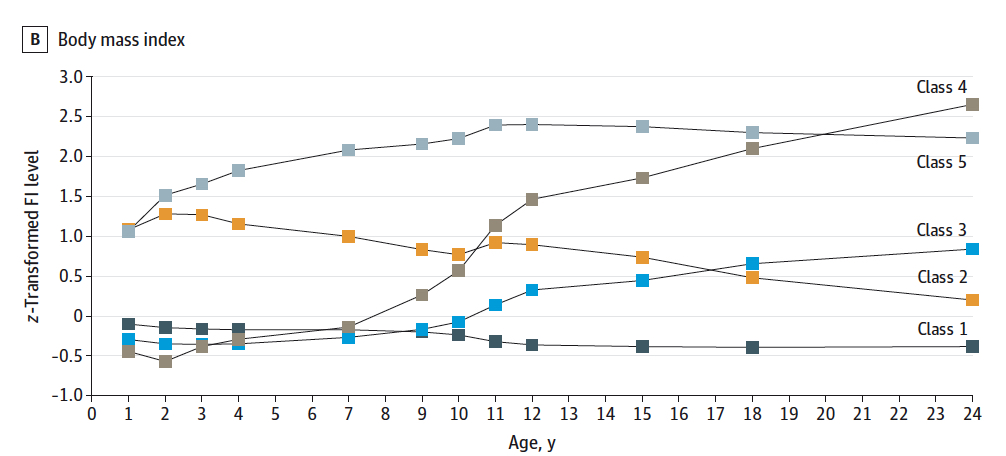

We were able to include up to 10k participants across 12 repeat measures of BMI from ages 1-24y, and 4 measures of insulin levels from ages 9-24y. We used a statistical technique called growth mixture modelling to help us answer the question.

Growth mixture modelling is cool because it groups people who have similar trajectories of change from repeat measurements, and from that, you can test associations with an outcome after taking into account the uncertainty in putting an individual in a particular group.

We found three distinct trends in insulin levels; stable average (class 1 – about 78%), minor increase (class 2 – about 19%), and persistently high (class 3 – about 3%):

and, 5 distinct trends in BMI. In a mo I’ll talk about stable average (class 1, about 71%), persistently high (class 5; about 6%), and puberty onset – major increase (class 4 - puberty onset – major increase, about 2%) trends. Stay with me

We found that a trend of persistently high insulin levels from childhood was associated with, compared to the stable average trend, a 3-fold higher odds of psychotic disorder which was assessed at age 24y.

This finding persisted after taking account a range of other possible explanations (confounders). We didn’t find strong evidence of an association of insulin trends with depression.

This suggests that disruptions to glucose-insulin homeostasis could be detectable quite a long time before the onset of psychosis in some individuals, and, that persistently raised insulin levels from childhood *could* be a risk factor for psychosis in adulthood.

For BMI, we found that the puberty onset major-increase trend was associated with a 4-fold higher odds of depression at 24y than the stable average trend.

We didn’t find strong evidence of an association of the persistently-high BMI trend with depression, and we didn’t find strong evidence of an association of BMI trends with psychosis.

This result was interesting, because we might have expected to see an association between persistently high BMI levels and risk of depression, *if* raised BMI was indeed a risk factor for depression  .

.

.

.

We didn’t find this, and this suggests that BMI might be a risk indicator of *something else* that can lead to *both* increased BMI and the risk of depression in adulthood

.

.

.

.

We don’t know what this *something else* might be from our study, but given that it likely occurs around the age of puberty onset, it could be something biological to do with puberty  , or something external which could happen to young people at that age

, or something external which could happen to young people at that age  .

.

, or something external which could happen to young people at that age

, or something external which could happen to young people at that age  .

.

Future research might help to unpick this, because it could be an important preventative target(s) for both obesity and depression in adulthood!

Overall, our results suggest that the cardiometabolic risk associated with psychosis & depression may predate the mental disorder, underscoring the vital need for *all young people presenting with psychosis or depression to receive a comprehensive physical health assessment  *

*

*

*

Early assessment and intervention of both the psychiatric and physical health of our young patients is a great way to improve long term outcomes, and hopefully help to close the mortality gap.

Thanks to all my wonderful supervisors and collaborators who helped me with this work, the twitter-folk amongst them @JanStochl @RachelUTG @golam_khandaker

And, thanks to you for getting to the end! Go get yourself a healthy snack as a reward! :D

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter