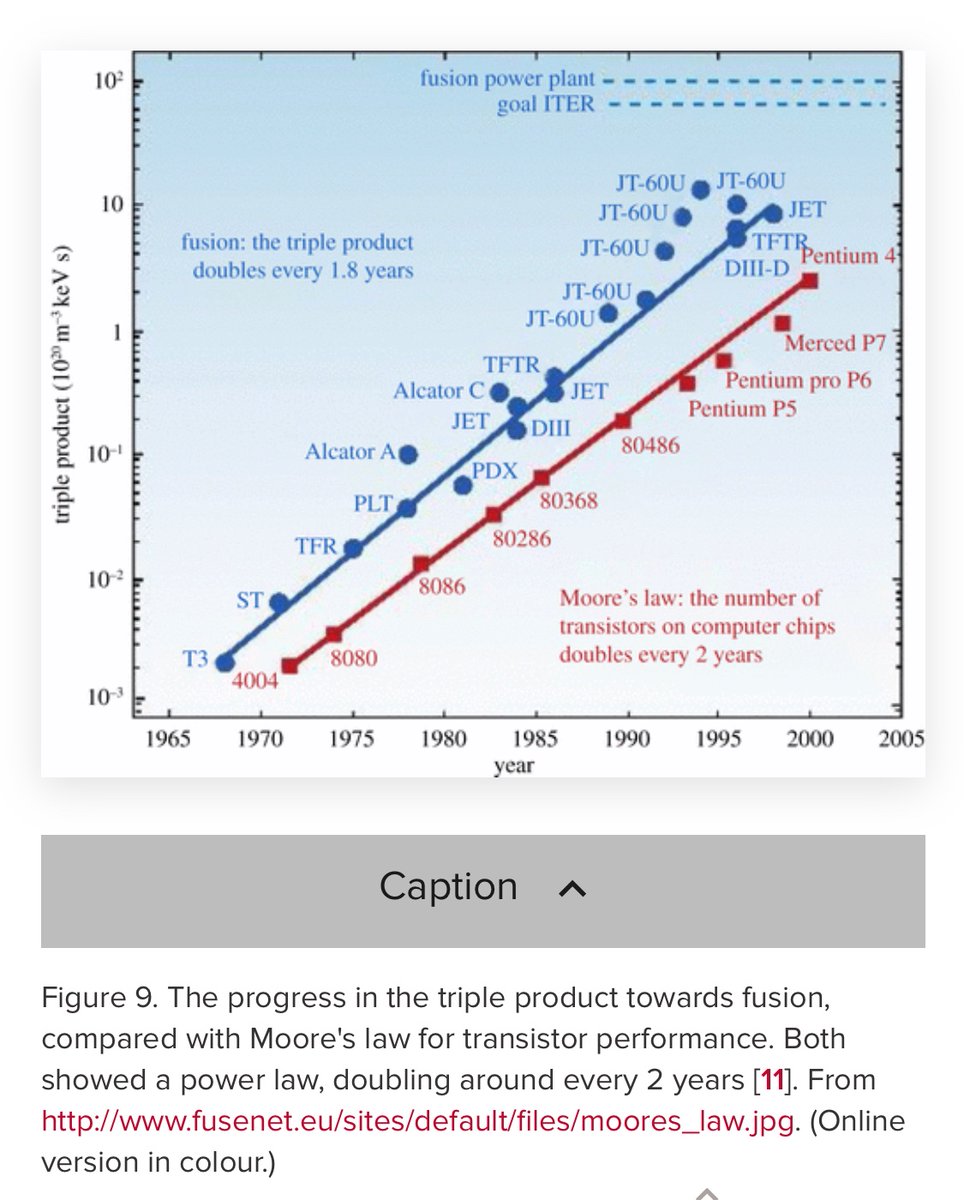

I came across this fascinating plot showing that the progress in #fusion energy *beating* Moore’s law up until the late 90’s

If we extend the trend line, we should have had the first fusion power plant by 2010!

If we extend the trend line, we should have had the first fusion power plant by 2010!

Imagine how much more prepared we would be for climate change if we had a limitless, load-following green energy source like fusion

This plot comes from this paper (Windsor 2019), which has a number of interesting historical details!

https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2017.0446

This plot comes from this paper (Windsor 2019), which has a number of interesting historical details!

https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2017.0446

This begs the question: why did progress in fusion stop in the 90s?

This question fits into recent interest in analyzing scientific and tech progress - so-called #ProgressStudies

The immediate reason is pointed out in the article. The next-generation fusion experiment, #ITER, is a multi-billion $, multinational project. Many huge, one-of-a-kind pieces to be built. Coordinating between countries is a barrier. Delays and cost overruns, especially early on

In the 90s, the leading fusion devices were university-and national lab-scale. But the best evidence at the time showed that the most likely path to achieve fusion energy would be a massive device like ITER

The only country on earth that could have afforded it was the United States, but given the stinginess of our elected officials to fund research (and perhaps their overexuberance to spend on fancy new weapons), we shouldn’t be surprised that never happened

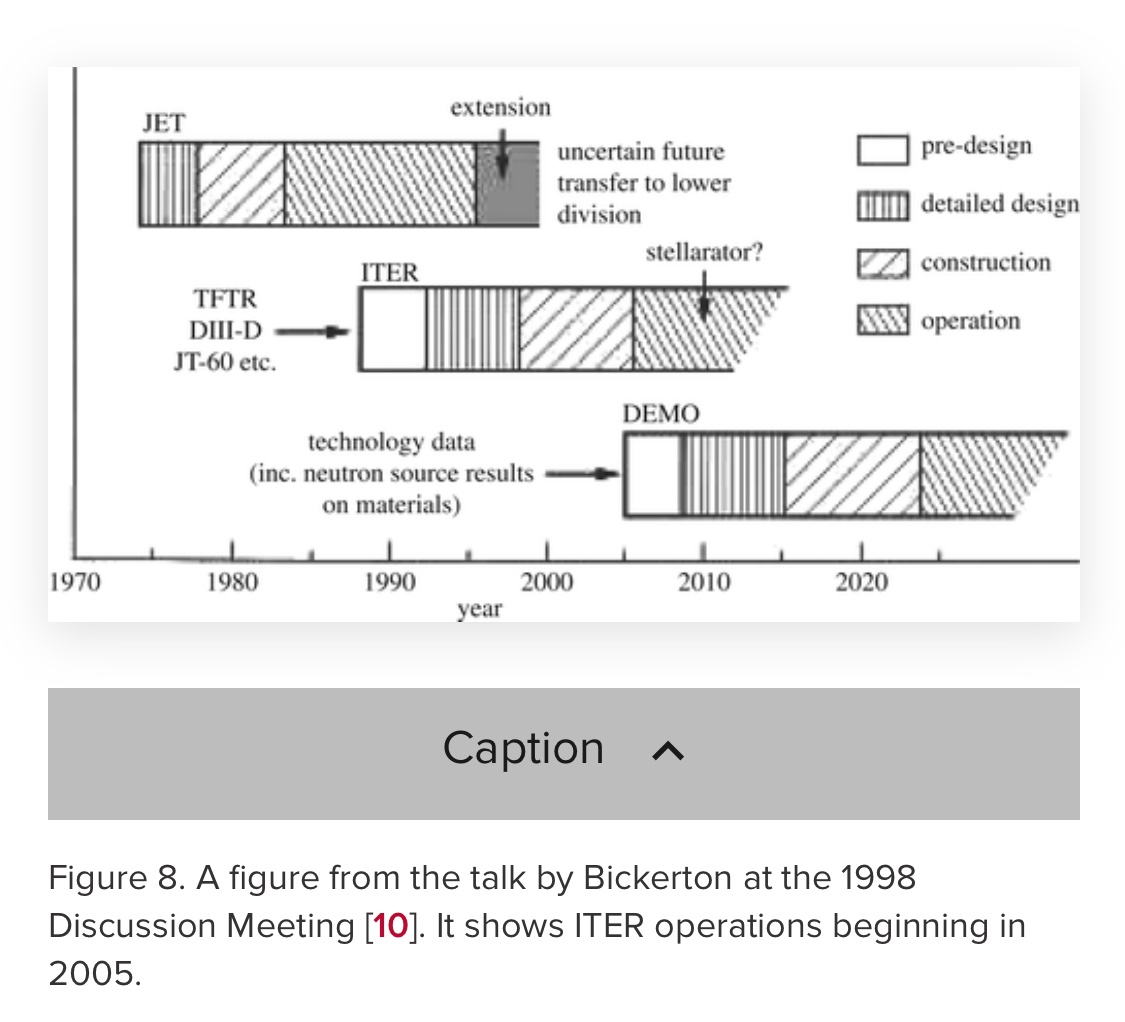

The original timeline was too ambitious given practical constraints. They first wanted ITER to be up and running by 2005 and a demonstration reactor (DEMO) before 2030

As of the latest update, ITER is slated to come online in 2025, but won’t start experiments with the net fusion energy-relevant fuel until 2035. DEMO has been delayed to the 2050s

Nevertheless, ITER will be one of the greatest engineering feats achieved by humanity and ranks among the most excited experiments we will see in our lifetimes. The complexity of the project, the scale of the facility, and the vast number of collaborators

And hell, it’ll probably get net fusion energy!

So to summarize, the immediate reason why fusion power progress slowed down dramatically after the 90s was because the challenges of constructing a megaproject - coordinating stakeholders around the world to build massive, custom-order components, etc. But...

... this begs the question, why did ITER need to be a megaproject? Why did researchers in the 90s think that net fusion power couldn’t be achieved on a smaller, more affordable scale? Do we know any better now  ?

?

?

?

I’ll take a crack at those questions in a future thread(s) since this is getting quite long. Let me know if you have any questions or if I missed something!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter