Some lessons from Boone Pickens's high stakes games in the oil patch.

“Looking back, it seems as though I have spent my whole life raising money for a deal.” https://neckar.substack.com/p/boone-pickens-high-stakes-games-in

“Looking back, it seems as though I have spent my whole life raising money for a deal.” https://neckar.substack.com/p/boone-pickens-high-stakes-games-in

"Like many business executives, owe my success to the free enterprise system. I started with a good education, $2,500 in capital, and an opportunity to do something—the sky was the limit, and fortunately the same opportunity still exists."

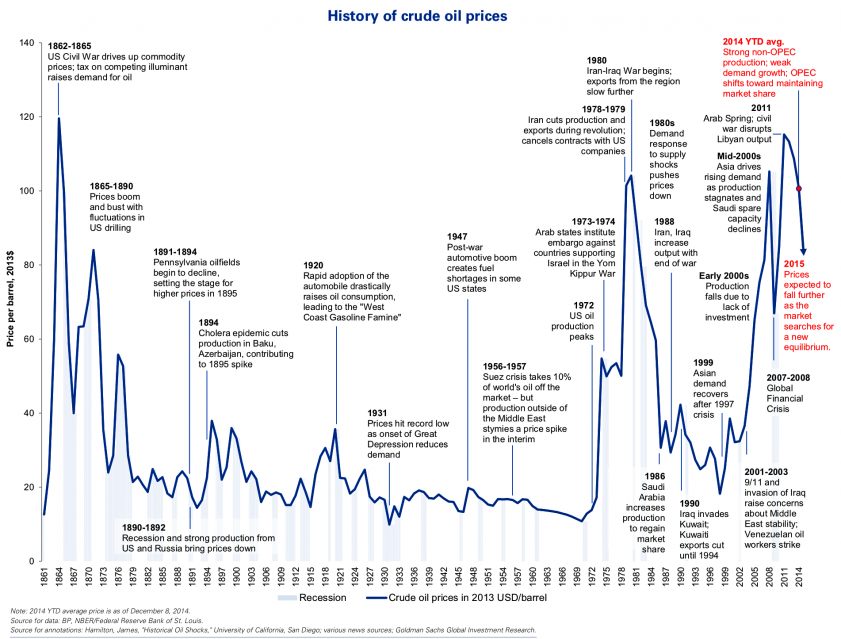

His life tracked the energy cycle.

Built Mesa Petroleum in the quiet period post WW2 .

Went offshore during the energy boom.

Pivoted to raiding public markets in the 80's.

Mesa went bust in the 90's.

Reinvented himself as a HF manager and rode the bull market of the '00s.

Built Mesa Petroleum in the quiet period post WW2 .

Went offshore during the energy boom.

Pivoted to raiding public markets in the 80's.

Mesa went bust in the 90's.

Reinvented himself as a HF manager and rode the bull market of the '00s.

“I often did better in a down market. There was less competition, land prices were lower, and drilling was cheaper.”

“Reserve replacement is like a treadmill. It just keeps coming around, year after year. The bigger the company gets and the more oil and gas it produces, the more oil and gas it must replace.”

Out of college he joined a large company as a geologist. It wasn't a good fit: “Nobody stays in the building after hours, and you have been staying sometimes until 6pm.”

His wife: “If you hate it so much, why don’t you just quit?”

And so he did, with $2,500 and a pickup truck.

His wife: “If you hate it so much, why don’t you just quit?”

And so he did, with $2,500 and a pickup truck.

“This was what I was born to do. It became clearer once I was actually out there on my own, putting deals together. The most important thing is that it was just plain fun. Feeling the pure joy of work and success is necessary for an entrepreneur.”

His bootstrapping formula:

Know the local opportunity set intimately: find promising drill sites.

Know all the players: land owners, drillers.

Create value by connecting ideas with capital. Get paid for the deals.

Know the local opportunity set intimately: find promising drill sites.

Know all the players: land owners, drillers.

Create value by connecting ideas with capital. Get paid for the deals.

“The key to making deals was for me to develop “drillable” ideas. I would return to the office at night and work on my maps, looking for places where another well might be drilled. Once I had a prospect, I then started looking for an investor to drill the well.”

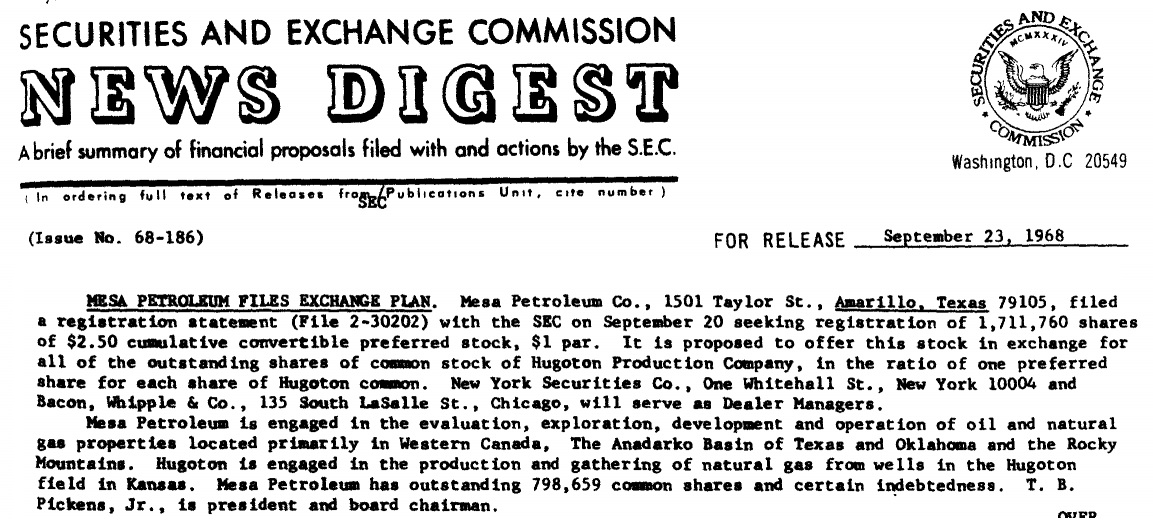

The next step was to become a principal: he found partners for his company and raised drilling funds to spread the risk.

“It was up to me to find the investors. Asking people for money is the most essential skill for a young dealmaker. It was as hard as anything had ever done.”

“It was up to me to find the investors. Asking people for money is the most essential skill for a young dealmaker. It was as hard as anything had ever done.”

He figured out that buying undervalued energy companies could be a better way to get reserves than drilling.

“Our growth was steady but slow, and I was impatient.”

With no track record he had to go the extra mile and once herded cows with a skeptical shareholder.

“Our growth was steady but slow, and I was impatient.”

With no track record he had to go the extra mile and once herded cows with a skeptical shareholder.

In the early 80's he found himself levered and heavily invested in the Gulf of Mexico. With too many dry holes and declining oil prices he needed a new idea.

“Boys, this is it. We’ve got to figure out a way to make $300 million and we’ve got to make it fast."

“Boys, this is it. We’ve got to figure out a way to make $300 million and we’ve got to make it fast."

He felt big oil companies were undervalued, poorly managed, and not interested in shareholders.

“Although most CEOs own a few thousand shares of stock, their value as an incentive is insignificant compared to that of the four P’s: pay, perks, power, and prestige.”

“Although most CEOs own a few thousand shares of stock, their value as an incentive is insignificant compared to that of the four P’s: pay, perks, power, and prestige.”

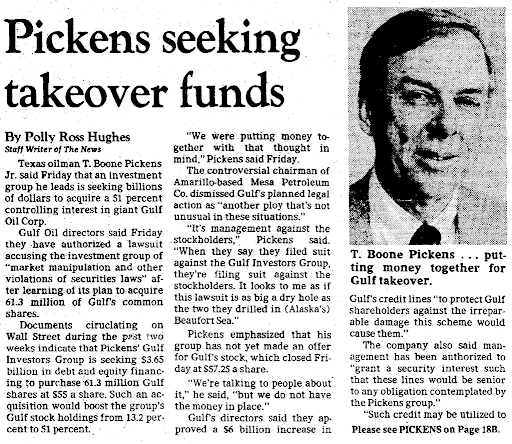

His biggest battle was Gulf Oil, 20x Mesa's size.

Despite its size, the conditions were right: management had lost its credibility on the street by withdrawing from a prior deal. And Pickens now had a track record and could line up equity partners and financing from Milken

Despite its size, the conditions were right: management had lost its credibility on the street by withdrawing from a prior deal. And Pickens now had a track record and could line up equity partners and financing from Milken

When he wasn't given a podium at the shareholder meeting: “I appreciate your giving me the chance to speak today from the same level as the Gulf employees and stockholders. Frankly that’s where I feel most comfortable.”

Gulf was sold to Socal, forming Chevron.

“A crusader never makes money, I don’t want to be one. There were 400,000 shareholders that came out making $6.5 billion. We happen to be one of the stockholders, the largest, and we made $500 million."

“A crusader never makes money, I don’t want to be one. There were 400,000 shareholders that came out making $6.5 billion. We happen to be one of the stockholders, the largest, and we made $500 million."

"Managements of certain companies are convinced that they’re the owners. That’s not so. The stockholders are the owners. It’s incredible to me to see some directors have zero ownership. Yet they profess to represent the stockholders.”

While he liked to criticize Big Oil for squandering capital, his own days as an operator were numbered. He had drunk the drilling koolaid and in the 90's would be pushed out of his company. But I'll save the story of his reinvention for another day.

“Geologists generally have a tendency to be overly optimistic because of the nature of their business. You can get a string of dry holes that could destroy some guys, but you can’t give up. You have to think that the next one is going to hit a big field for you.”

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter