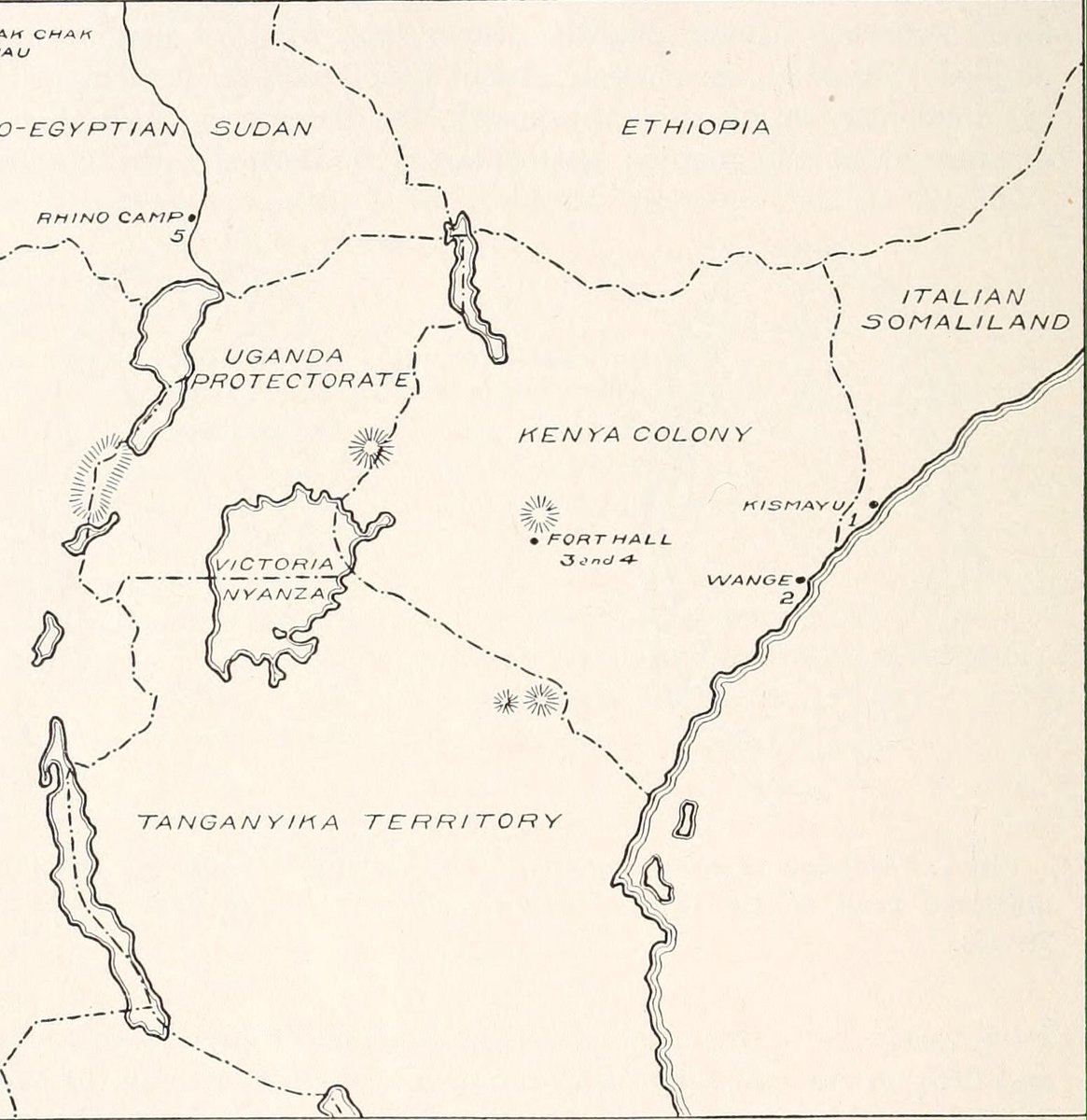

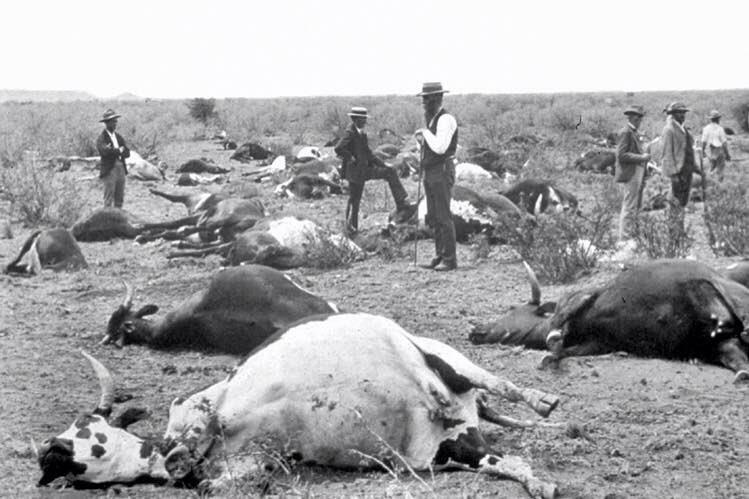

#HistoryKeThread Once upon a time in 1889, the hinterland of what would later become the territory of Kenya was hit by rinderpest.

The scourge reportedly wiped out up to 90% of entire herds of livestock of some communities, notably the Maasai, Kamba and central Kenya tribes.

Some families of the Kamba ventured into Embu, Meru and Gîkûyû countries foraging for food.

Later in the mid-1890s, there was an outbreak of bovine pleuropneumonia, followed by a locust calamity that wiped out crops in 1898, which was the same year rinderpest made a return.

Later in the mid-1890s, there was an outbreak of bovine pleuropneumonia, followed by a locust calamity that wiped out crops in 1898, which was the same year rinderpest made a return.

The catastrophes triggered a series of migrations particularly from grain-deficient Kamba and Maasai communities to territories of their neighboring communities.

Officials of the IBEAC (Imperial British East Africa Company) noted that these migrations helped spread smallpox, a disease that was mostly endemic among the Kamba.

The mortality rate among the Kamba due to disease and famine was estimated at twenty five thousand. In addition, they like other communities in the country lost tens of thousands of livestock.

Side note: From records of IBEAC, rinderpest spared stocks of goats, but was fatal to sheep and cattle alike.

One of the consequences of this dark episode of misfortune was that it altered the socio-cultural norm amongst affected communities.

One of the consequences of this dark episode of misfortune was that it altered the socio-cultural norm amongst affected communities.

Families that were previously wealthy – by the African measure of heads of livestock, that is - suddenly found themselves poor and miserable. For want of livestock, desperate Kamba and Maasai communities “loaned” their women in exchange for grain.

In 1974, two Embu elders, Elijah Kimani and Habili Kibui, interviewed by researcher Kabeca Mwaniki, author of “Embu Historical Texts”, recalled the unconventional famine trade. “The Kamba first brought livestock for foodstuffs. Later, they brought their wives and children…..”

Swedish ethnographer Gerhard Lindblom who authored Kamba Folklore (1934), alluded to dalliance in prostitution by Kamba women when he had words of a song sang by Kamba women translated. The literal translation of the song went as follows:

“When it rains very little, we are deprived of women, who vanish to nearby townships to dig with their back…”

Kambas were not the only ones who pledged their women for food. The Maasai did the same.

Kambas were not the only ones who pledged their women for food. The Maasai did the same.

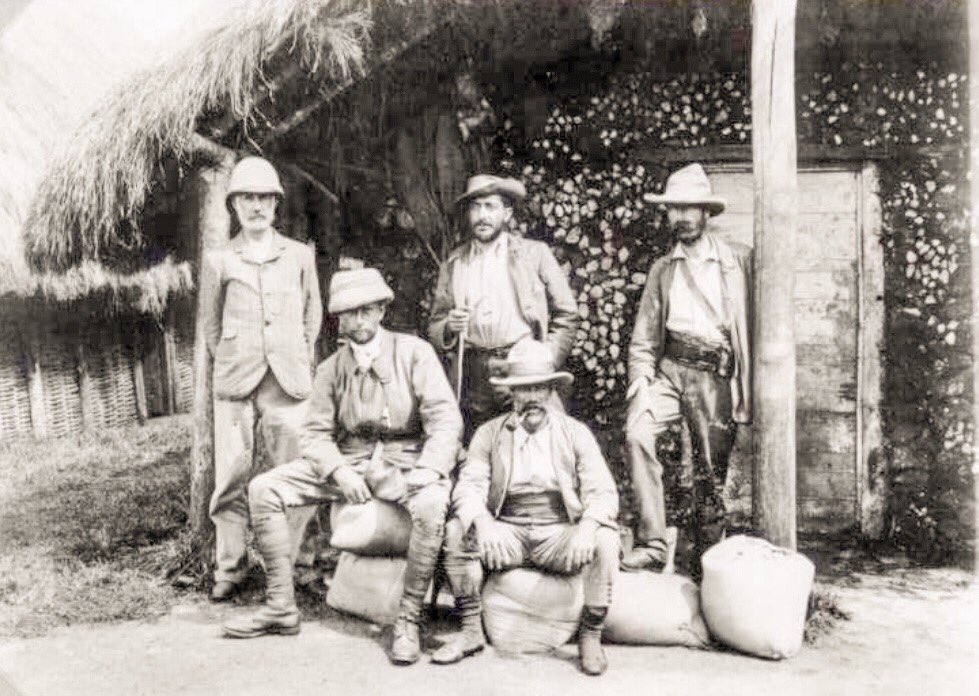

In 1893, according to letters by IBEAC’s Francis Hall (standing, center), there were many Maasai families camped near Fort Smith in Kikuyu.

When their numbers swelled to a few thousand, the Company moved them to Ngong, which according to the administrator became a haven of pawned, captured and runaway Maasai women until the end of the decade.

After 1905, pawning decreased considerably, at least among the Maasai. 1905 was the year in which Col. Richard Meinertzhagen of the IBEAC killed Nandi leader Koitalel arap Samoei.

The Englishman’s “Nandi Field Force” employed a scorched earth policy, burning granaries and farmlands of the Nandi. The force also drove away large herds of cattle, which were subsequently bequeathed to the Maasai as war booty (in the war against the Nandi, Maasai warriors...

....were recruited to fight on the side of IBEAC).

Some may rightly argue that by encouraging pawning, communities perpetrated a form of human trafficking or, if you like, prostitution, which mostly served patriarchal interests.

Some may rightly argue that by encouraging pawning, communities perpetrated a form of human trafficking or, if you like, prostitution, which mostly served patriarchal interests.

What is clear is that scarcity of food or livestock created a fertile ground for community inter-marriages or, arguably, forced marriages.

After the increase in 1919 of Hut and Poll taxes on Africans by the colonial administration, aging parents encouraged their adult sons to take up various paid jobs so they could help ease the tax burden.

Besides, those who tilled farms in the village felt farm work was not prestigious. They considered those among them who got employed in Nairobi or towns along the Uganda railway line as cooks, clerks, railway workers or even soldiers to have landed the real deal.

It is this waged labour force that gave rise to commercial sex work in urban areas.

Swedish ethnographer Gerhard Lindblom, who authored Kamba Folklore (1934), alluded to dalliance in prostitution by Kamba women when he had words of a song sang by Kamba women translated.

Swedish ethnographer Gerhard Lindblom, who authored Kamba Folklore (1934), alluded to dalliance in prostitution by Kamba women when he had words of a song sang by Kamba women translated.

The literal translation of the song lyrics was as follows:

“When it rains very little, we are deprived of women, who vanish to nearby townships to dig with their back…”

“When it rains very little, we are deprived of women, who vanish to nearby townships to dig with their back…”

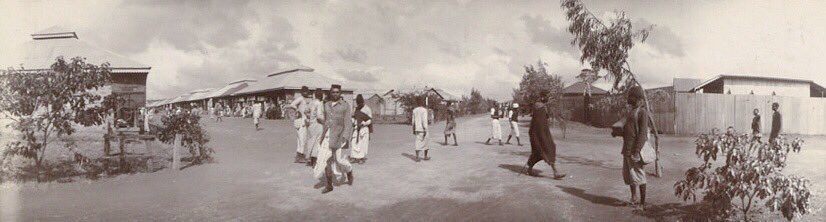

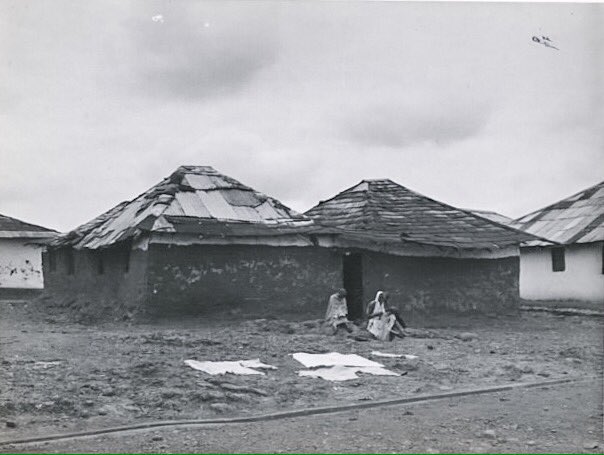

In Nairobi, Kileleshwa village, located in present-day Kileleshwa, Nairobi, and demolished in 1926, Pangani and Pumwani were considered hotbeds of commercial sex (in 1927, the Native Affairs Department of the colonial administration reported that out of 25,000 Africans...

....working in Nairobi, an estimated 20,000 of them were adult males in registered employment).

Rural women also came to Nairobi in search for work. But Nairobi had a disproportionately higher population of African men.

Rural women also came to Nairobi in search for work. But Nairobi had a disproportionately higher population of African men.

Accordingly, housing favoured male workers. The few women in the budding town “had to secure their position as tenants in a highly competitive housing market”, as Luise White, author of The Comforts of Home: Prostitution in Colonial Nairobi, wrote.

According to her, the circumstances inevitably led some of the women to venture into commercial sex work. Most of them were single and had travelled mostly from areas adjoining Nairobi.

And because customs required that they be married, whenever they became pregnant, the baby would later be killed or abandoned.

Indeed, E.R. Davies, the “Native Affairs Officer” for Nairobi in 1939 decried the infanticide that took place in Nairobi from the late 1920s through to the 1930s.

Most women were single and had travelled mostly from areas adjoining Nairobi, mainly central Kenya, Ukambani and Maasailand. There were a few who were Kalenjin.

Ostracised by or detached from their families, many of them got converted to islam at the behest of their muslim landlords. But as Janet M. Bujra, author of Women Entrepreneurs of Early Nairobi noted, only Maasai commercial sex workers refused to be converted.

Sometime in the 1980s, author Luise interviewed a woman, Hadija Njeri, who moved to Pangani as a teenage girl in 1918.

According to Hadija, she was adopted at Pangani by a muslim woman she referred to as Mama Asha.

According to Hadija, she was adopted at Pangani by a muslim woman she referred to as Mama Asha.

“She's my first mother because she's the one who helped me when I came to Nairobi. She is the one who gave me my first place to live, she taught me to speak Swahili, and she's the one who gave me the new name of a Muslim woman”, said Hadija.

She also recalled the infanticide of the 1920s.

“”You know, in those days no man would love you if you already had a baby. Most of the girls, they waited until the baby was born and then they would kill the baby or abandon it to die”.

“”You know, in those days no man would love you if you already had a baby. Most of the girls, they waited until the baby was born and then they would kill the baby or abandon it to die”.

She went on:

“In those days you couldn't tell your real mother that you were pregnant, your real mother would never allow you to have a baby when you weren't married, she must not know, she would never allow for me to let the child live....”

“In those days you couldn't tell your real mother that you were pregnant, your real mother would never allow you to have a baby when you weren't married, she must not know, she would never allow for me to let the child live....”

“..... Many prostitutes here in Nairobi had old woman mothers who cared for them and gave them names like Marna Asha did for me....”

In a previous post, we alluded to the fact that clusters of built up African housing areas in various towns in Kenya were referred to as Majengo, for “buildings”.

I wonder if Hadija’s account explains why many towns today that have an area called Majengo have inhabitants who profess the muslim faith, but who do not necessarily come from traditionally muslim communities

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter