Despite everything, I have a new paper with @timothyjlayton @borisvabson @AdelinaYWang: https://www.nber.org/papers/w28331

Distract yourself from the woes of the world by reminding yourself about the woes of privatized health insurance markets!

1/17 (I know. I promise it’s worth it.)

Distract yourself from the woes of the world by reminding yourself about the woes of privatized health insurance markets!

1/17 (I know. I promise it’s worth it.)

2/ We know people make mistakes in health insurance choice. We know less about *why* and what policies matter for the “behavioral”. We think default rules matter a lot, just as in retirement savings and organ donation. Our focus: Low-income subsidy program in Medicare Part D.

3/ Big premium and cost sharing subsidies. Many plans free to enroll, diff is in what drugs are covered/restricted. And unusual default rules: Sometimes, default is to be assigned to a *randomly-chosen* free plan. We observe those default assignments and whether they get followed

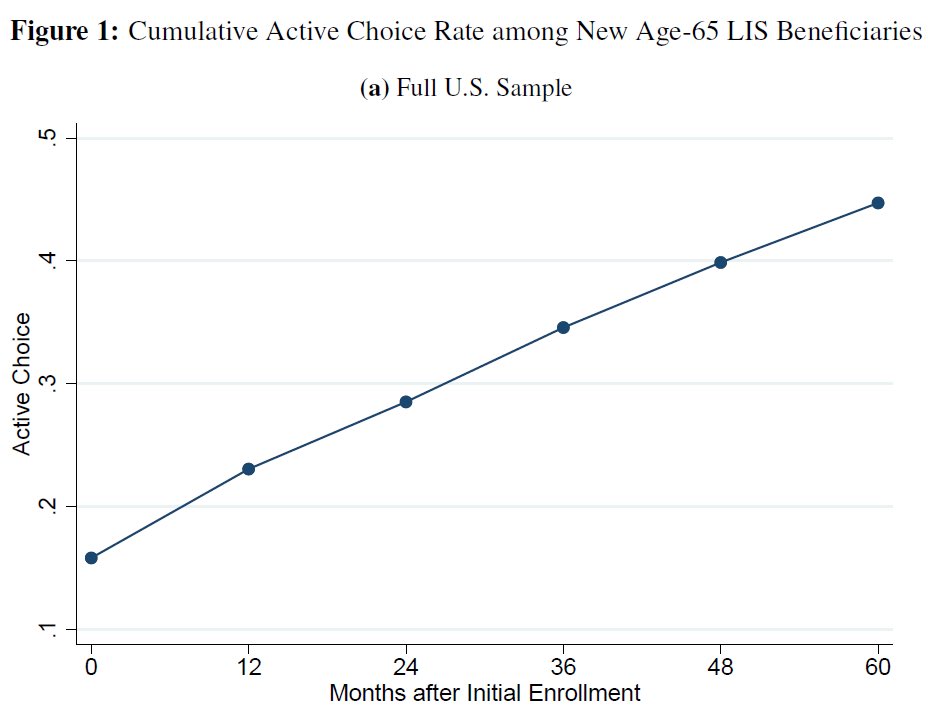

4/ Buys us three natural experiments. Experiment 1: What happens when they turn 65 and enroll for the first time? A: Only 16% make initial active choice, 84% randomly assigned! After five years (age 70) only 45% have *ever* chosen a plan. Defaults matter.

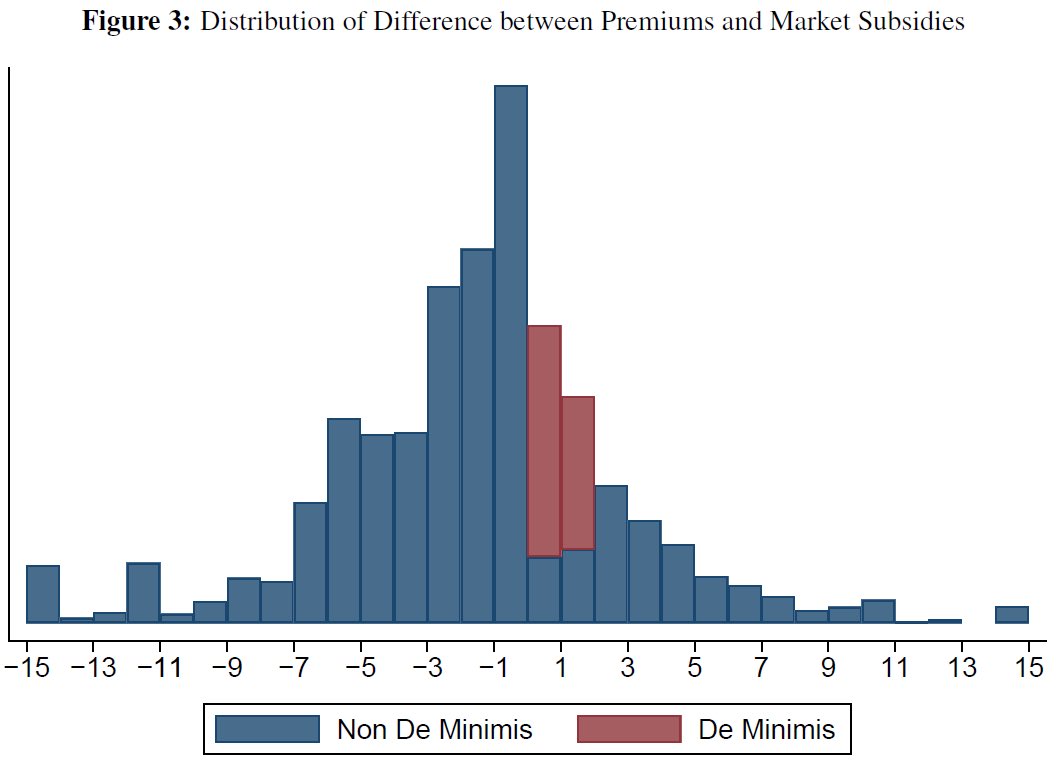

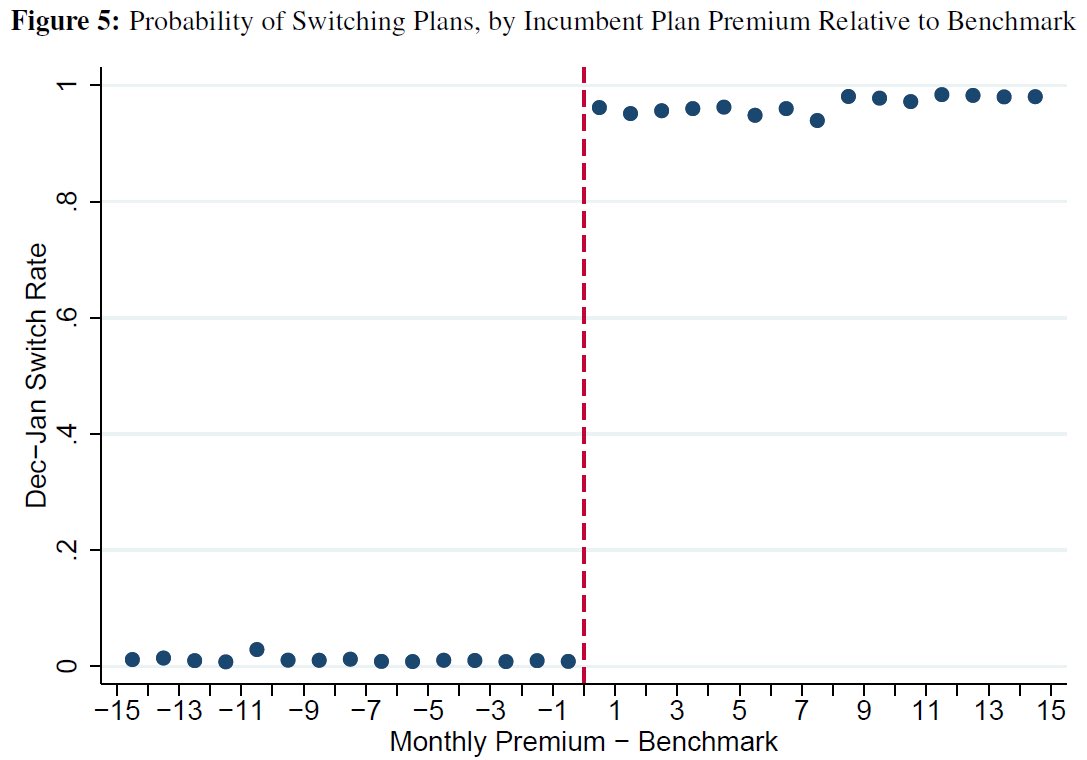

5/ Experiment 2: Default from year to year is to remain in plan. Unless your plan’s premium goes above the premium subsidy (and you were originally auto-assigned to it). Then your default becomes reassignment to a random plan. Is this an RD? Yes!

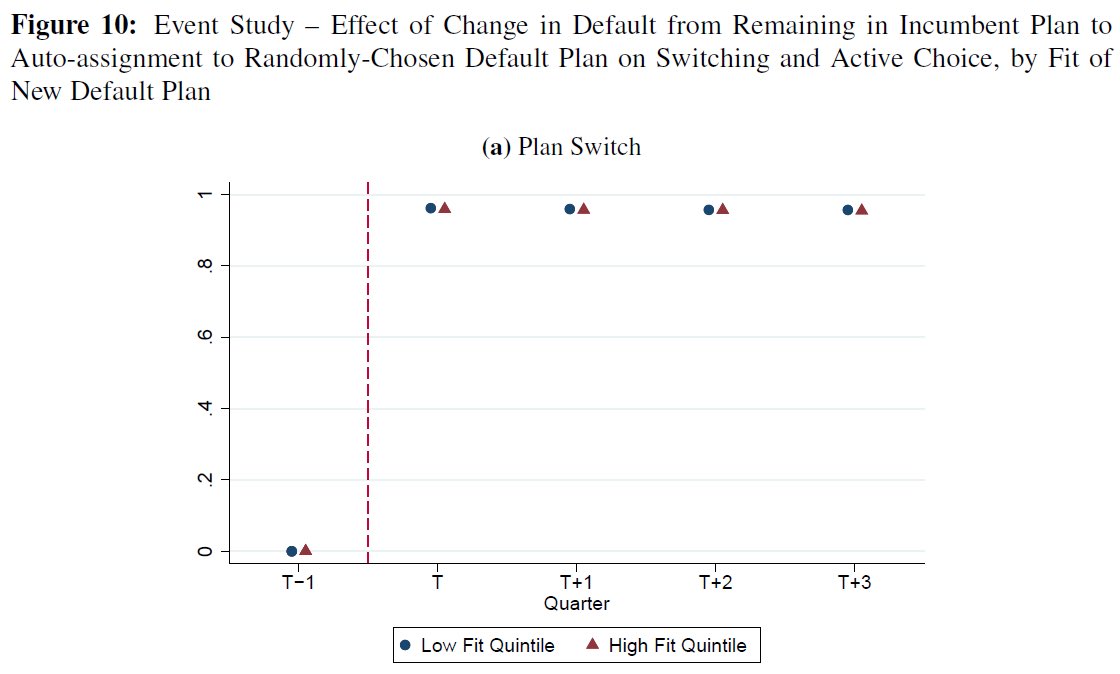

6/ When the default is to stay in the same plan, <1% switch plans from year to year. When the default is to switch plans, 97% switch plans. Defaults matter! People apparently not willing to pay small $/month to remain in their plans.

7/ Ok, they matter. How to optimally design? Two schools of thought: 1) “Nudge” approach a la @R_Thaler: make default appealing to help non-choosers; 2) “shock” people by giving them such a bad default that they are forced to make a choice. Theory can prescribe either!

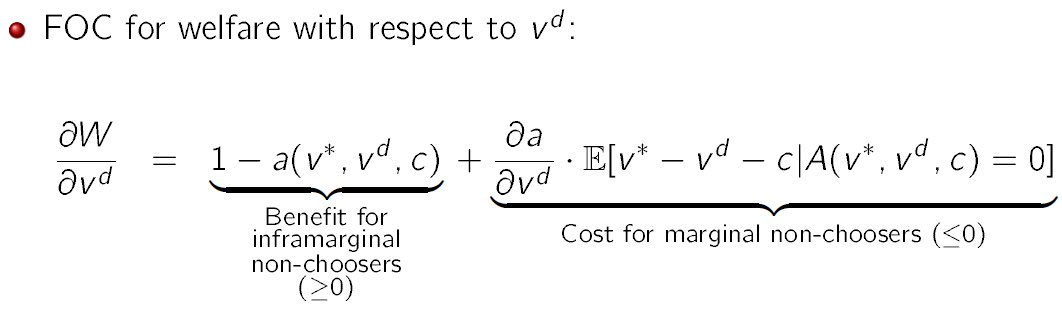

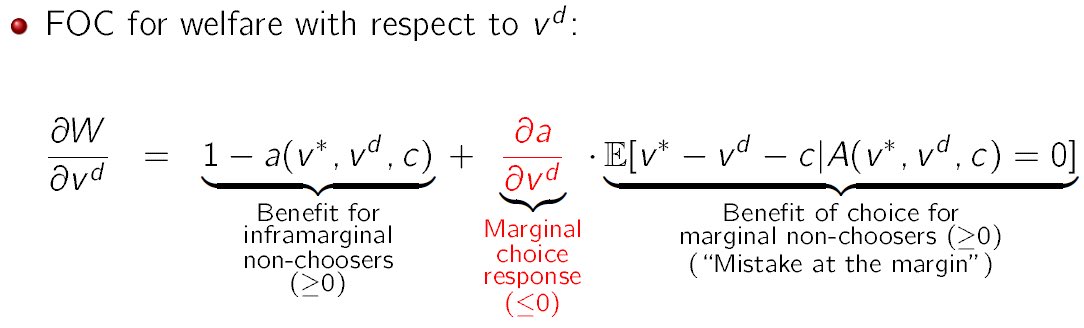

8/ We take first-order approach a la opt. tax theory. What happens if you make the default better by $1? Two effects: Existing default followers (non-choosers) $1 better off. But some enrollees newly induced to take default, bad for them if they’re making a mistake by doing so.

9/ Big assumption: People respond to defaults getting better by paying less attention! Consequence of typical models (inertia a la @BenHandel 2013, rational inattention, costly search) but not obviously true. If not, no trade-off: Make defaults paternalistic to help people.

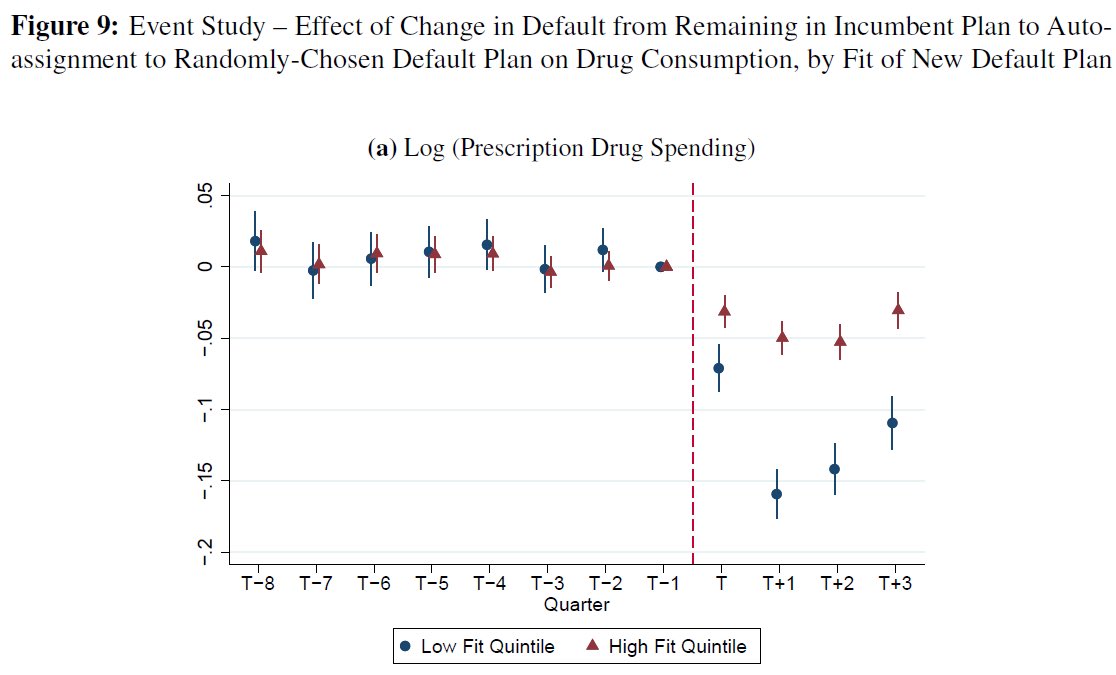

10/ First, let’s prove beneficiaries should even care about the default. Return to exp. 2: How does default change affect drug consumption? Compare above/below threshold pre/post. Facing a default of reassignment -> drug consumption down 6.5%.

11/ What if your default is really bad? We rank the plans you could have been assigned by how well they cover your preexisting drug patterns. What if you get randomly assigned to the worst 1/5th of plans for you? Lose 12.4% of consumption instead of 4.4%!

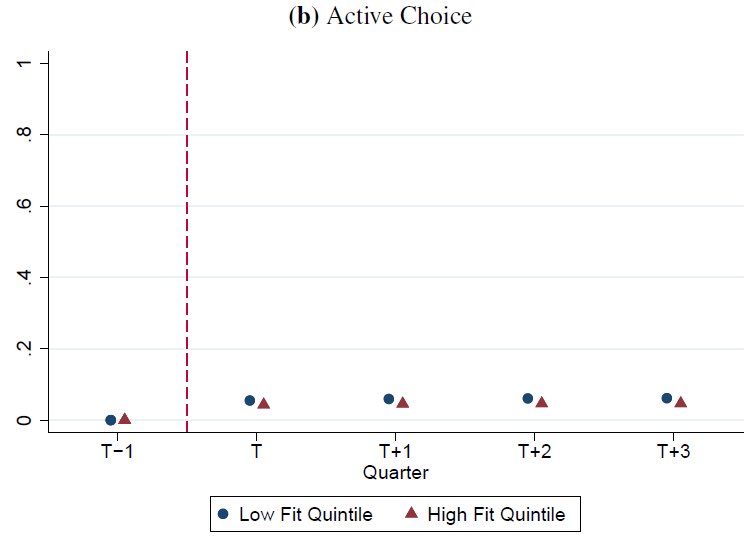

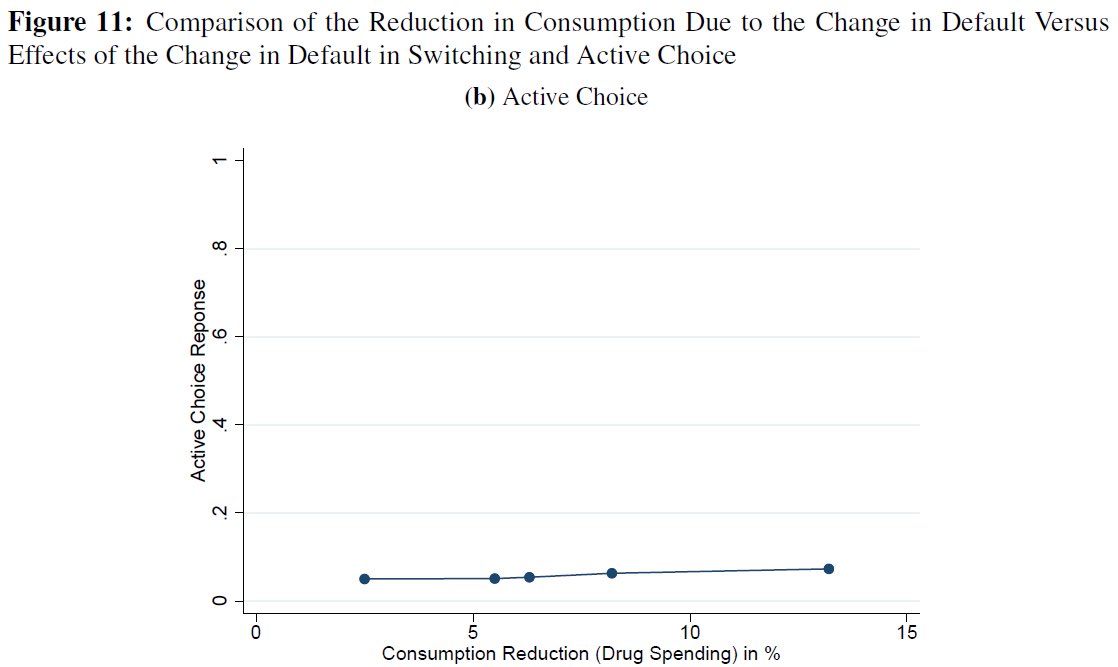

12/ Getting worse default assignment -> ~no more/less likely to switch plans (1) or opt out of default (2). We can plot the “badness” of the randomly-assigned default against the probability of opting out (3). Slope ~= 0!

13/ Harsh defaults don’t shock people into action! And yet we have many harsh defaults. Trump admin proposed default to *lose subsidies* in ACA. How costly would that have been for enrollees?

14/ Wait, didn’t I promise 3 experiments? Yep. Experiment 3: If your plan exits, default random re-assignment no matter how you got into that plan. If you made a choice before, do you make one again? Are some people better at being ‘choosers’? A: Yes, but not by much (25% vs 7%).

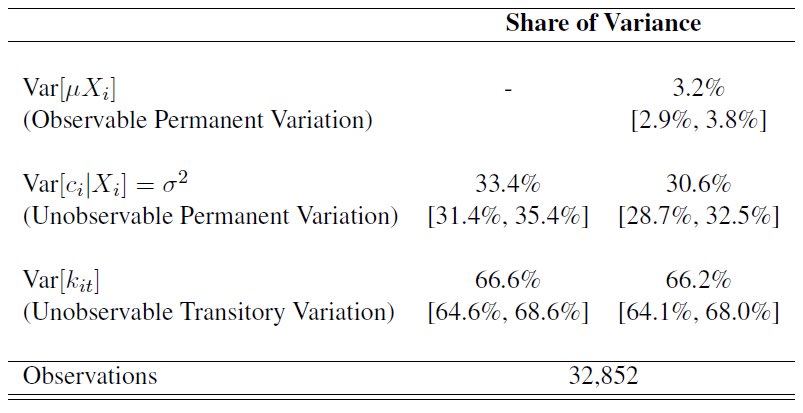

15/ Simple structural calibration: 1/3 of variation in who follows defaults is about who you are (your ‘type’), 2/3 is just random. Who follows defaults? Everyone! (sometimes)

16/ The upshot: People are sporadically and randomly paying attention to big decisions about social insurance. We need to do better at supporting them when they don’t pay attention. Defaults/nudges are at least as important as your other favorite insurance market design tool.

17/ And a little bit of editorializing: What does this say about what we get out of choice in social insurance for the low-income? We can’t get people to pay attention, why do we think they can discipline the market?

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter