Spain, 1936. Five years of escalating political tension explodes into widespread violence. Though mostly ignored or distorted by popular histories, the bitter struggle that followed would set the stage for World War II. This thread will cover the origins of the Spanish Civil War.

First, background. Spain at the start of the 20th century was unaffected by the great lifestyle shifts of its neighbors. Only a few areas were industrialized. The population remained largely rural and agrarian. Power was centralized in an almost feudal manner.

At the heart of this centralization was Miguel Primo de Rivera, the Prime Minister, placed into power by military coup in 1923. With the approval of King Alfonso XIII of, he ruled the nation as a dictator, forming an alliance of landowners, the military, and the Catholic Church.

Inspired by Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, de Rivera embarked on a massive infrastructure campaign, bringing electricity to many areas of the country for the first time. He kept the peace with an iron first, censoring the press and banning far left political parties.

Spain fought a bitter struggle in the remnants of its colonial empire. Distinguishing himself in Morocco was Francisco Franco, founder of the Spanish Foreign Legion. These ruthless units turned the tide and pacified the region. Franco was made Brigadier General at the age of 33.

De Rivera’s agenda alienated landowners, but kept him popular. Buoyed by this success, he moved to liberalize his government. However, Spain’s economic boom soon ended. Right-wingers blamed de Rivera's reforms for the problems and the Left never forgave his earlier repression.

Seeing the writing on the wall, de Rivera resigned. However, Alfonso XIII was unsuccessful in his attempts to restore ordinary constitutional order, tarred with his earlier support of the dictatorship. Liberal parties won decisive electoral victories in important urban centers.

Unpopular and blamed for Spain’s declining economic position, Alfonso XIII abdicated and fled the country. The Second Spanish Republic was formed to replace the monarchy. Anti-reactionary and anti-Catholic sentiment swept the country. Churches in Madrid and Sevilla were burned.

The Second Republic immediately set about implementing a number of liberal policies. The nobility was stripped of special status, suffrage was expanded, and freedom of speech and association were enshrined in the constitution. Spain would be dragged into the modern era.

The Catholic Church, seen as the heart of Spain’s conservative establishment, was the immediate target of the new government. Church property was heavily regulated and sometimes nationalized. Members of religious orders were barred from teaching positions. Pope Pius XI protested.

Violence against the Church escalated in 1932, with another arson wave that was ignored by the government. Legislators turned their attention to "land reform”, looking to break up the large estates which dominated the countryside and transfer ownership to the peasantry.

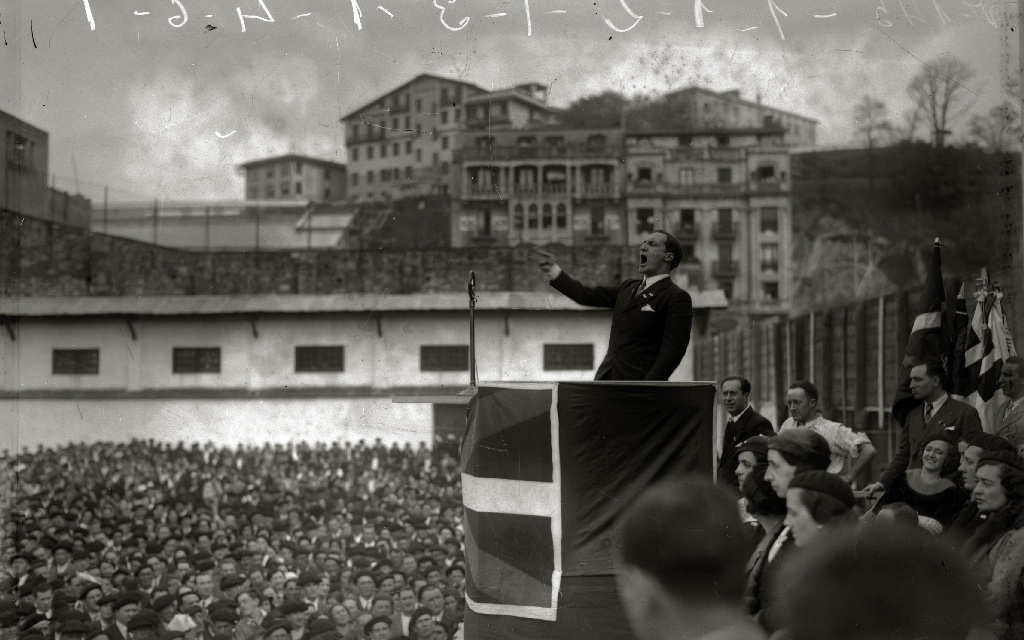

The Second Republic set about dispersing as much power as possible, attempting to prevent conservatives from ever consolidating as they had before. Huge concessions were granted to previously-suppressed regional autonomy movements in Basque Country and Catalonia.

Monarchist military officers, fearing the breakup of the country, staged an uprising against the current government. However, it failed to gain wide support and was crushed largely without violence. The coup plotters fled the country or surrendered themselves to the new Republic.

Minor political factions emerged as national powers. In the Basque Country, the traditionalist Carlist movement rekindled. In Catalonia anarchist unions swelled their numbers to tens of thousands. The fascist Falange and Socialist Party consolidated strength. All create militias.

These radical changes rattled the general public. In 1933, a coalition of center- and far-right political parties won the election and rolled back many of the more unpopular “reforms”. Far-left groups lost interest in the parliamentary process. Street violence became widespread.

In 1934 a general strike in Asturias led by socialist and anarchist groups turned into open rebellion. Clergy and military officers were massacred. The government deploys General Franco and his legionnaires, who crush the uprising with brutality not seen on the mainland in years.

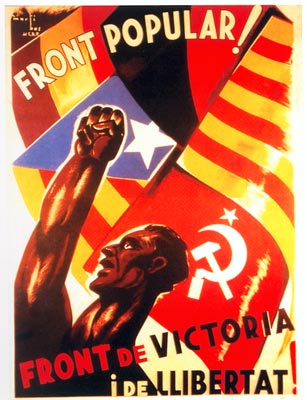

The Soviet Union began to heavily invest itself in politics across Europe, encouraging “Popular Front” movements in several nations. These groups were designed to unify liberal, socialist, and communist parties into a single Soviet-controlled coalition against "fascism."

In 1936, elections were called. The Spanish Popular Front promised only liberal reforms rather than a Bolshevik revolution. The liberal-left coalition secured a narrow victory over its right-wing counterpart. Manuel Azaña became prime minister despite allegations of fraud.

After its victory the Popular Front government immediately released thousands of “political prisoners”, including rebel fighters captured during the 1934 uprising. Impatient with the promised reforms or disinterested in government altogether, left-wing street violence escalates.

Azaña attempted to reform the military, purging the officer corps, arresting those accused of abuse during the Asturias uprising and moving commanders suspected of conservative leanings to far-flung posts. Franco is reassigned to an unimportant position in the Canary Islands.

The Popular Front boosted parallel institutions. Urban intellectuals were sent to rural areas to teach in an effort to reduce the power of the Catholic Church in education. The Assault Guards, created by the 1931 leftist government, grew into a powerful political police force.

Mob violence spiraled out of control. Political assassinations became commonplace. The Popular Front remained indifferent to attacks against right-wingers or passively supported them. In the countryside peasants seized land and lynched landlords.

In early July of 1936, popular Assault Guard lieutenant José Castillo is assassinated by Falange gunmen. In response the Assault Guards arrest José Calvo Sotelo, a widely-respected conservative Member of Parliament, and murder him. His body is dumped in the street.

The murder is greeted with outrage by moderates and conservatives across Spain. Thousands attend his funeral. High-ranking military officials, who had long been building support in the ranks for a coup, decide that the time for their uprising is at hand.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter